October marks the centennial of what remains by far the greatest scandal in American sports history. When eight members of the Chicago White Sox—known forever after as the Black Sox—threw the 1919 World Series, the betrayal reverberated far beyond the burgeoning sports industry. Occurring as it did in a moment of dizzying social change in America, it jolted the nation’s idea of itself. Indeed, in retrospect, the affair stands as one of those signal events that define an era. Americans were never quite so innocent again about sports—or anything else.

Thanks largely to the films Eight Men Out and Field of Dreams, the Black Sox are now firmly embedded in popular culture. As dramatic storytelling, the saga has all the elements: not just avarice and betrayal, but unexpected heroism, genuine poignancy, and moral complexity, with the perpetrators just as easily seen as victims. “Say it ain’t so, Joe,” the heartbroken little boy’s plea to fallen star Shoeless Joe Jackson, was probably a sportswriter’s invention, but it’s not for nothing that it still tugs the heartstrings of even those who don’t know Hank Aaron from Aaron Judge.

On the eve of the 1919 World Series, the White Sox were unquestionably baseball’s best team. Three players on its roster would eventually enter the Hall of Fame, and there might have been twice that many had the fixers been eligible for consideration. Even now, Jackson, the illiterate South Carolina sharecropper’s son, is ranked among the game’s greatest hitters. Eddie Cicotte, a 29-game winner in 1919 who was en route to the magic 300-win milestone, had a superlative career earned-run average of 2.38; and at 26, Lefty Williams, the team’s Number Two starter, was proving nearly as dominant.

But the White Sox also had the game’s most tight-fisted owner, Charles Comiskey, and, in an era when players were bound to their teams for life by the Reserve Clause, he exploited even his stars. Some of them, anyway—a sharp class divide existed on the ballclub, and it played out both in the locker room and in the pay differential. While the canny, Columbia-educated future Hall of Fame second baseman Eddie Collins (known to resentful teammates as “Cocky” Collins) earned $15,000 that season, the blue-collar Cicotte was paid barely half that. Yet, it was not Cicotte’s salary but a clause in his contract that proved decisive to what followed: he was guaranteed a $10,000 bonus in the unlikely event that he won 30 games that year. Once Cicotte reached 29, though, with five starts still to go, Comiskey ordered manager Kid Gleason to stop using him.

The Sox’s Game 1 starter in the series, Cicotte had been reluctant to commit to the fix—but when he promptly hit the Cincinnati Reds’ leadoff batter, it was a signal that the deal was on. Given that the superiority of the White Sox was reflected in the betting odds, the first indication that something might be amiss—at least for those paying attention—was that so much money had suddenly been wagered on the underdog Reds. Several sportswriters who knew the team intimately, including the legendary Ring Lardner, made note of the improbable plays that seemed to occur at just the wrong moments—a bobble or misplayed fly ball here, a boneheaded decision there—and with grim humor came up with a parody of a popular standard:

I’m forever blowing ballgames,

Pretty ballgames in the air,

I come from Chi, I hardly try,

Just go to bat and fade and die.

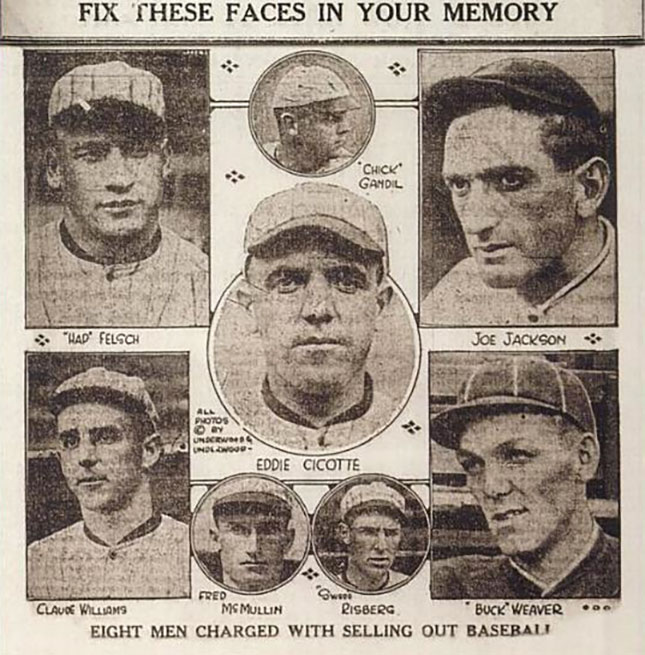

The Reds would go on to win what was then a best of nine series, five games to three. Yet for the Sox, the games would produce one unlikely hero in the person of the unheralded lefthander Dickey Kerr. The team’s third starter, unaware of his teammates’ subterfuge, Kerr pitched so brilliantly that the Sox won both his starts. (What’s less remembered is that Kerr’s career ended soon thereafter, when he was suspended by Comiskey and subsequently blackballed for holding out for better pay.) It would be a full year, the closing days of the 1920 season, before everything came to light, but once it did, photos of the disgraced eight dominated front pages everywhere. It remains difficult to fathom the scandal’s impact on the public, one almost unimaginably less jaded than we are today. “He’s the man who fixed the World Series back in 1919,” F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote five years later in The Great Gatsby, in introducing Meyer Wolfsheim, modeled on real-life fix mastermind Arnold Rothstein.

“Fixed the World’s Series?” the novel’s narrator Nick Carraway marvels:

The idea staggered me. I remembered, of course, that the World’s Series had been fixed in 1919, but if I had thought of it at all I would have thought of it as a thing that merely happened, the end of some inevitable chain. It never occurred to me that one man could start to play with the faith of fifty million people —with the single-mindedness of a burglar blowing a safe.

In fact, the timing made perfect historical sense. The recently concluded slaughter in Europe had changed America in ways just becoming apparent. Rather than peace and prosperity, the First World War’s conclusion produced widespread unemployment and dislocation. Fear of anarchism was rampant, and so, too, was racial violence—much of it generated by a reborn Ku Klux Klan. Cynicism was in the air; America’s prolonged age of innocence was over.

Indeed, even as the public grappled with the scandal, the nation’s attention was jolted by the ugly underside of another major cultural institution, with the shocking news that screen beauty Olive Thomas had died after swallowing poison in a Paris bathroom. It was soon revealed that the doe-eyed ingénue was a “drug fiend.” It was the first in a series of Hollywood scandals, including, most notoriously, Fatty Arbuckle’s multiple trials for rape and manslaughter and the murder of hotshot director William Desmond Taylor that recast Tinseltown as America’s Sodom.

Still, the disillusionment prompted by the Series fix was of a greater magnitude. Baseball was then at the zenith of its popularity and influence, truly America’s pastime. Boys by the millions grew up reading books extolling its heroes, learning vital lessons about effort and fair play; the game was celebrated in popular song and from the vaudeville stage; presidents opened seasons throwing out the first ball. Now it was coming out that ballplayers had consorted with gamblers for decades.

But if the newspapers had missed that story—or, more accurately, failed to cover it—the irony was that they missed an even more consequential deception sitting in plain sight. Just a month after the fixed series, as he roamed the country vainly trying to rally support for the League of Nations, President Woodrow Wilson suffered a devastating stroke that left him an invalid for the remainder of his term. Throughout those crucial 15 months, Wilson’s wife and personal physician concealed the severity of his condition from the world, keeping him in isolation so strict that Wilson’s own vice president never saw him. Rarely had sports served as a more convenient distraction from appallingly dangerous behavior at the top. Little wonder that the Republicans’ pitch in 1920—a return to “normalcy”—so captured the spirit of the times.

Yet if voters were eager to close the book on Wilson and the Democrats, baseball’s mandarins had little confidence that people were as ready to forgive their game—not with the eight alleged fixers set for trial, and with more bad news on the way: ten days after Election Day, they named federal judge Kennesaw Mountain Landis baseball’s first commissioner. As craggy and austere as his name suggested, Landis—who, years earlier, conveniently, had won the owners’ confidence by preserving the Reserve Clause—was granted absolute power over the game. His first move was to ban the eight players for life, an edict that he refused to reconsider even when, the following year (key evidence having mysteriously vanished), they were acquitted in a courtroom. In later years, Landis would steadfastly resist repeated pleas, notably from Jackson and third baseman Buck Weaver, for reinstatement. Weaver, the narrator of my Black Sox novel, Hoopla, was an especially intriguing case: though he knew of the fix, he apparently didn’t participate in it, and in fact he performed well in the series.

In any event, bringing on Landis worked so well that Hollywood soon hired a “czar” of its own, in former postmaster general Will Hays. But baseball got lucky. Traded after the 1919 season from the Red Sox to the Yankees, pitcher-turned-full-time outfielder Babe Ruth started slugging at a hitherto unimagined pace, and during the Roaring Twenties the game would rise to new heights of popularity. Landis, for his part, lorded over the sport until his death in 1944. He was as vigilant in safeguarding baseball from gamblers as he was unwavering in his support for the Reserve Clause—and the ban on black players. Happily, in vital respects, he would scarcely recognize the game today.

Of course, it’s still the case—ask Pete Rose—that consorting with latter-day Arnold Rothsteins is baseball’s ultimate sin, calling forth the ultimate punishment. Yet if not precisely a contradiction, it’s at least an oddity, a century later, that gambling on sports has never been seen as less sinful. Indeed, in a time when state legislatures vie with bookies for citizens’ paychecks, gambling—like pot-smoking and prostitution—has gained wide acceptance.

Not that in the current scheme of things, it’s even possible to buy off professional athletes (well, maybe a benchwarmer). How much would it cost to induce a modern-day Cicotte, guaranteed $24 million on a six-year deal negotiated by a super-agent, to blow a game? It’s no mystery why the fix scandals of recent decades have involved either amateurs—college hoopsters, induced to point-shave—or, in one memorable case, a pro referee. For the same reason, it’s no surprise that baseball’s most recent major scandal involved the use of performance-enhancing drugs. While many things have changed in the past century, avarice and human frailty are not among them.

Which gets us, inevitably, to the great Hall of Fame debate. Should Jackson and perhaps Cicotte at last be admitted? And from there: how about Barry Bonds and Roger Clemens or Mark McGwire? And does it matter that Rose apparently never bet against his own team? Those are questions that, in a time when moral standards are no longer universal, each of us answers according to his own lights. And, of course, we ask them not just about athletes, but notables across the vast celebrity universe, from Louis C.K. to Bill Clinton. What is fundamentally wrong, and what is merely inappropriate? What merits career death instead of censure followed by forgiveness or compassion? In the past, such questions were rarely asked, certainly not about public luminaries, for the answer—“off with their heads!”—was obvious. That approach wasn’t always entirely just, but it certainly reflected moral clarity.

So, pondering the Black Sox and their legacy gives rise to a more pertinent question: Were we better off then? Was it healthier for children, and even their elders, to live in a world where those in the news, and in the history books, stood as unblemished models of achievement and virtue? Of course, it was illusory, as lots of people knew even then. But it was a comforting illusion, and more than that, it helped hold us together as a nation. That world is gone, but 100 years on, there’s a lot to be said for it.

Top Photo: Wikimedia Commons/Public Domain