Last month, the Biden administration unveiled a plan to ramp up forest management to address the catastrophic wildfires scorching large areas of the western United States each year. Its report, “Confronting the Wildfire Crisis,” calls for $50 billion over the next decade for forest thinning, prescribed burning, and other hazardous-fuels treatments designed to reduce extreme fire risks. If fully implemented, the plan would increase these activities by up to four times current levels, with a focus on communities near fire-prone forests.

Biden’s plan is the strongest signal yet that active forest management—viewed as a Republican talking point just a few years ago—has become a bipartisan issue in Washington. The infrastructure bill passed by Congress last year provides a $3 billion down payment for the initiative. Biden’s strategy calls for many billions more to carry out fuels treatments on 50 million acres of public and private lands, where dangerous fuel loads have accumulated after decades of fire suppression. The administration is pitching its plan as a “paradigm shift” in federal forest management, away from an approach focused on stamping out all wildfires to one that manages forests for fire resilience.

It’s a step in the right direction. The U.S. Forest Service has identified 63 million acres of national forests at high risk of extreme wildfires, yet the agency has treated just 2 million acres annually in recent decades. Addressing the problem will clearly require significant funding. But confronting the wildfire crisis will take more than new spending. It will also mean addressing a thornier issue: cutting through the environmental red tape that prevents many forest-restoration projects from getting off the ground or stalls them until it’s too late.

Citing the record-setting fires of recent years, the report calls the wildfire crisis a “national emergency.” Fire suppression has radically altered the condition of America’s forests, resulting in larger, more destructive wildfires that threaten communities, pollute the air, degrade water quality, and destroy wildlife habitat. Drought and a warmer climate are making the problem worse. Today’s megafires burn so intensely that they can threaten forests’ capacity to regenerate.

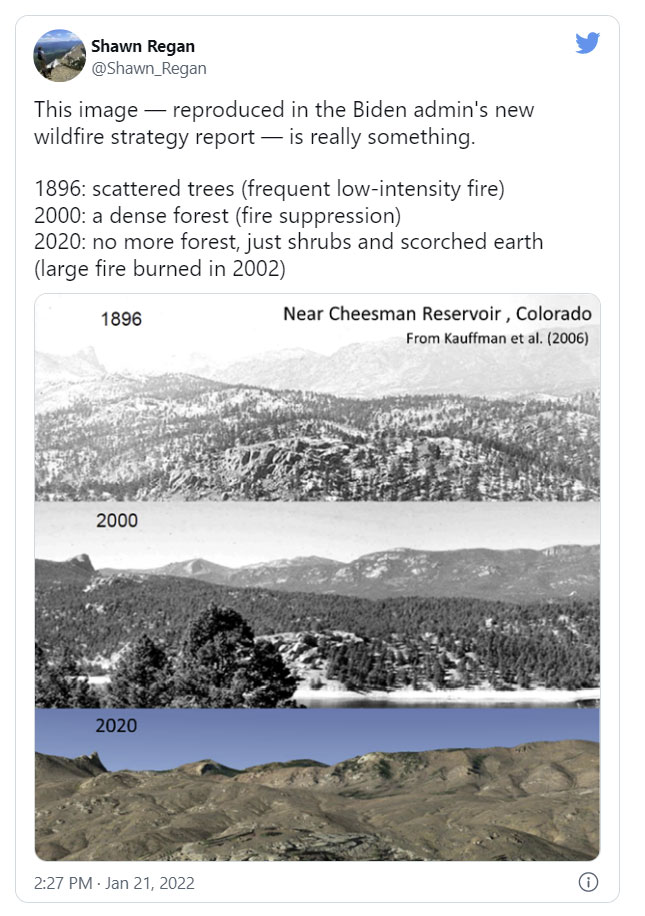

Biden’s report highlights a series of images captured near Colorado’s Cheesman Reservoir, which supplies water to Denver (see below). One photograph, taken in 1896, reveals a landscape lightly scattered with trees due to frequent, low-intensity wildfires. The same image, captured in 2000, shows a dense forest that has built up after a century of fire suppression. A third image, from 2020, shows a moonscape of scorched earth. After a severe fire burned in 2002, the forest never recovered and is now dominated by shrubs.

Avoiding such outcomes, however, requires addressing the bureaucratic and legal barriers that thwart restoration projects. A recent investigation by the Sacramento Bee describes how anti-logging activists often abuse federal laws such as the National Environmental Policy Act and Endangered Species Act to stall forest-thinning projects, despite broad recognition from fire scientists and conservation groups that such activities are needed. Activists held up a 9,000-acre thinning project in California for a decade over concerns that it would harm endangered spotted owls, only to see the area burn in a fire last year that destroyed the birds’ habitat. One woman’s lawsuit over another California forest-thinning project forced the government to process 19,193 pages of paperwork. The project remains in limbo today.

Overcoming these challenges won’t be easy. An environmental-review process that favors inaction over active management needs reexamination. In its first two years, Biden’s plan will focus on forest-thinning projects that have already gone through environmental analysis but lack funding. Carrying out new projects at scale will be more difficult. Projects can take years to develop, as agencies must prepare extensive environmental reviews that can withstand litigation; even then, many get tied up in court.

Other regulatory obstacles will need to be addressed. Smoke from prescribed fires is regulated under the Clean Air Act, which limits its use. (Wildfire smoke, by contrast, is not regulated). Getting the necessary approvals from state air-quality regulators can also be onerous. NPR recently reported that burn permits can be approved in minutes in states like Florida, where controlled burns are commonly used, but can take months to obtain in heavily regulated states like California, which has long failed to carry out enough prescribed burns.

Creative funding approaches will also be needed. The “forest resilience bond,” an innovative financing tool recently developed by the nonprofit Blue Forest Conservation, is one potential model. Under this approach, investors provide upfront funding for forest-restoration projects and are paid back over time by beneficiaries of healthier forests such as utilities, local governments, and private businesses. A recent pilot project in California raised $4 million for fuels treatments in a fire-prone watershed in the Tahoe National Forest, allowing the work to be completed several years faster than originally expected.

Biden’s wildfire plan is a step in the right direction, but the hard part remains. If red tape and other regulatory challenges get in the way, no amount of federal funding will enable us to confront the wildfire crisis.

Photo by PATRICK T. FALLON/AFP via Getty Images