As President Biden’s weak debate performance continues to erode his standing in the polls and the credibility of his reelection campaign, not to mention his presidency, observers may wonder why the Biden team continues to operate as though nothing has happened. Every day brings news of elected Democrats or major donors openly imploring Biden to terminate his campaign. With early voting in some states set to begin in September, time is running short if the party wishes to “swap in” a new candidate at the top of the ticket.

Democratic leaders are in a bind. Biden remains popular with the party’s rank-and-file, who are less concerned about swing-state opinion polls, “electability” questions, or down-ballot considerations than are party insiders, who obsess over these matters. It nevertheless appears obvious to many observers that the president, whose legendary “gaffes” are beginning to look like unambiguous signs of dementia, will eventually have to come up with a dignified way to exit the race. But doing so ahead of his nomination poses significant problems for Democratic Party leadership. After all, the Democrats are fractious by nature—but even more so now. The party includes an extraordinarily broad spectrum of opinion. Some senior members believe that Israel is a pariah state; others are hawkish Zionists. The party includes socialists who seek to end private markets in housing and health care and fiscal centrists who voted against Biden’s economic agenda. The party has built this unlikely coalition on a foundation of minority identitarianism and “inclusion,” so representation at the level of race, ethnicity, gender, and sexual orientation is a central concern in forming consensus.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

This factionalism is helpful as a means of attracting voters who feel disenfranchised, but much less so when it comes to facing something as contentious as an open convention, which is essentially the proposal being pushed by people calling for Biden to withdraw. An open convention, in which no candidate has secured a majority of votes ahead of time, hasn’t occurred in either party since 1952, when it took multiple ballots before Adlai Stevenson won the Democratic nomination.

If Biden bows out before getting nominated, one can easily imagine a host of candidates emerging to replace him. Even if, as many prominent voices are urging, Biden throws his support to Vice President Kamala Harris, his pledged delegates will be allowed to vote for a candidate of their choosing. Elements in the Democratic Party would prefer other candidates besides Harris, whose own electability is a major question. Progressives dogged her 2020 campaign, for example, with taunts of “Kamala is a cop,” referring to her supposedly tough-on-crime stint as California attorney general, and delegates in favor of police abolition could easily support someone else. Her 2020 run fizzled out months before the first primary.

Though not much is expected of vice presidents, Harris’s tenure has been especially mediocre. Soon after taking office, Biden assigned her the unenviable task of addressing the “root causes” of Central American poverty and instability; she told Latin Americans, “Don’t come” to the United States. Aside from that, Harris has become the subject of viral social media memes mocking her ramblings about overcoming the burden of time in multiple speeches, as well as for her characteristic cackle, which erupts at awkward moments.

Even if Harris were to win the nomination at an open convention, the Democrats are not in a position to risk the possibility of floor fights over her candidacy, her choice of running mate, the party position on Israel, and so forth. The embarrassing cover-up of Biden’s incapacity has already damaged the Democrats’ national credibility; public exposure of major ideological divisions within the party would not help their candidates in November. The Biden campaign’s current efforts to tread water, which many find mystifying, may reflect the Democratic leadership’s desire to carry the president over the line to the nomination, only then having him step aside in favor of a new candidate.

Political parties at every level maintain a committee on vacancies to deal with post-nomination absences, which can occur through death, dropouts, or other incapacitating events. According to the Charter and Bylaws of the Democratic Party, vacancies in the national ticket are managed by the Democratic National Committee (DNC) itself. The DNC is composed of true party insiders: the heads of all the state parties (and the highest-ranking officer of another gender); 200 other members apportioned by state population; the heads of various labor unions; senior Democrats in Congress; prominent mayors; representatives of “Democrats Abroad”; and so on.

This group, totaling about 500 people, would be called upon by the Executive Committee of the DNC to vote on filling a vacancy on the national ticket. The vote would require a quorum of half the members, who must actually be present to vote. The meeting would, presumably, be held in private, like a papal conclave. The committee members, all party regulars, would be able to pick a new candidate strictly on the question of electability, without regard to fringe opinion.

This scenario is hypothetical, of course, but the Democrats are in uncharted political territory. It is probable that every permutation is being analyzed in the party’s high chambers. Waiting until after the nomination to relieve Biden of his command would sacrifice transparency in favor of apparent harmony, but that may be a trade-off the mandarins are willing to make.

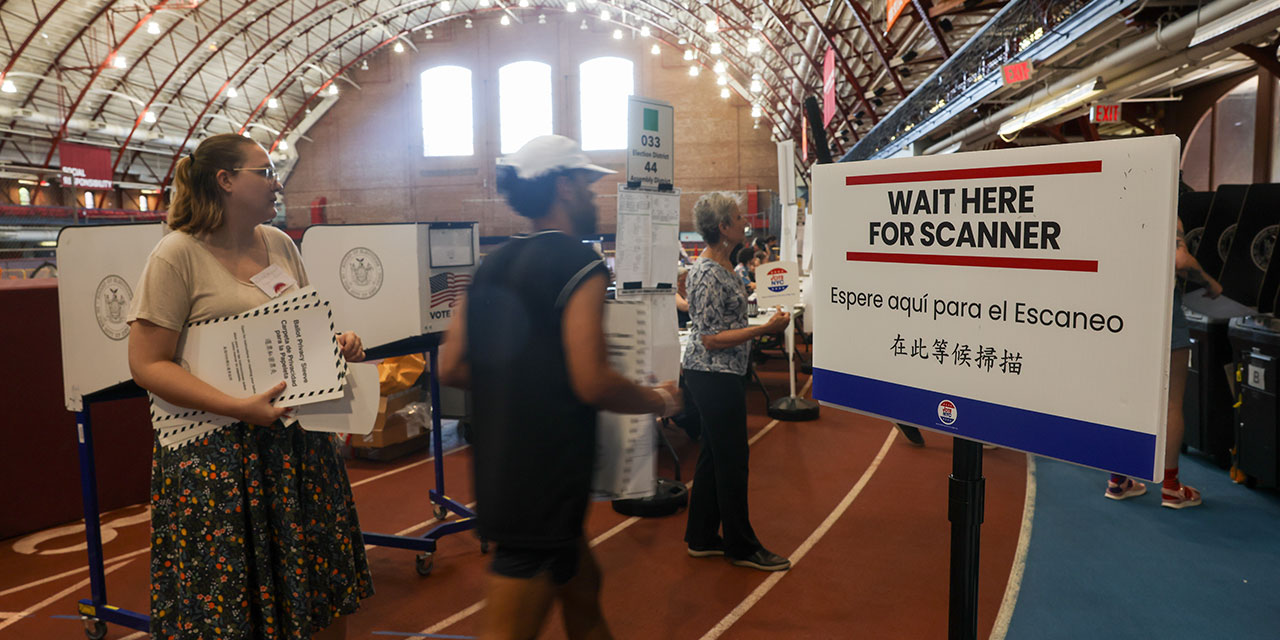

Photo by Joe Lamberti for The Washington Post via Getty Images