If you’re a Democrat, and your program is wealth redistribution—with a big cut for yourself as a ruling middleman—it turns out that racism is a much better rationale than inequality for robbing selected Peter to pay collective Paul. Inequality, as New York mayor Bill de Blasio ruefully found, is too fuzzy a cause to fire up most people with righteous indignation, since American liberty has always meant that people free to use their different talents and virtues in their own way will arrive at widely varying outcomes. But racism—oh, racism is the original American sin. It is so obviously, wickedly, unjust as to get the blood boiling in blue states and cities across the land.

Trouble is, there isn’t that much racism festering in the nation any more. It was Barack Obama’s political obsession, perhaps bordering on political genius, to convince a majority of Americans that it pervaded everywhere, like phlogiston, seventeenth-century science’s imaginary substance—invisible but supposedly ubiquitous and providing our ancestors with an explanation for the otherwise inexplicable phenomenon of combustion.

Accomplishing this task, though, required a massive rewrite of the American history of the last half-century. As recently as 15 years ago, there were a lot of people around for whom the civil rights movement had been a formative, firsthand experience. I don’t mean the race hustlers like Jesse Jackson and Al Sharpton. I mean ordinary people who had a deep commitment to ending racial segregation and discrimination and to winning equal opportunity for all Americans, regardless (as the mid-century slogan put it) of race, creed, or color. We had heard the speeches of Martin Luther King and yearned for the day when only the content of your character, not the color of your skin, would count; had known (or even been) Freedom Riders, rumbling south by the busload to help hitherto disenfranchised blacks register to vote; had seen Birmingham police commissioner Bull Connor stand by while the Ku Klux Klan beat those demonstrators and later set his own police dogs and fire hoses on the next peaceful group; had seen Governor George Wallace stand in the schoolhouse door to keep blacks out of the University of Alabama. We saw the moral force of that movement inexorably marginalize the racists, and the legal force of the federal government steamroll them, starting with Brown v. Board of Education in 1954 and gaining momentum when Deputy Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach, flanked by federal marshals and national guardsmen, forced Wallace to step aside as the first black students entered his state university in 1963, and when Congress the next year passed the epochal 1964 Civil Rights Act.

My generation lived through decades of what seemed a world-historical liberation. Before our eyes, as we saw it, Jefferson’s dream of an America based on the idea that all men are created equal had solidified into a reality at last. So indelibly etched on our memories were those heady times that on 9/11, when my left-wing baby-boomer neighbors spontaneously assembled at the Firemen’s Monument on Riverside Drive, candles in hand, all they could think of to solemnize the occasion was to sing not “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” but the civil rights anthem “We Shall Overcome.” If the Vietnam War was the shadow of our formative years, the civil rights movement’s success was the sunshine.

But like many admirable movements, even this one had its excesses. Equality of opportunity wasn’t enough, some insisted. We needed equality of results. Government and private institutions adopted numerical goals and quotas and tried to reach them through affirmative action—that is, through a supposedly beneficent discrimination by race, seemingly legal, since the Supreme Court, even in Brown v. Board of Education, had never repudiated Plessy v. Ferguson’s odious 1896 acceptance of racial discrimination. We got forced school busing to make student populations of each school mirror the racial composition of the region, and public education’s focus shifted from imparting knowledge to fighting racial disparity—or, as the progressive-ed schools put it, advancing social justice. Needless to say, the education of black kids improved not a whit.

Moreover, according to the cant of the 1960s and 1970s, poverty and racial discrimination were the supposed “root causes” of crime, so society, not the criminal, was ultimately responsible for lawbreaking, and it should be lenient in punishing those whom it had already victimized by creating the unjust environment that had formed them. The accurate, though unspoken and increasingly unsayable, assumption: violent criminals were disproportionately black. What ensued was an urban crime wave, with murders in New York averaging one every four hours during 1990. On top of that, the idea that America’s mistreatment of blacks required reparations turned the New Deal’s welfare program, Aid to Dependent Children, into the War on Poverty’s stigma-free fuel for perpetuating a nonworking intergenerational underclass of dysfunctional, government-dependent single-parent families.

Reinforcing all these changes in attitude, I argued long ago in The Dream and the Nightmare, were shifts in the American elite’s standards for its own behavior in those same years. The celebration of pre- and extramarital promiscuity, along with the destigmatization of divorce and out-of-wedlock pregnancy, subverted family stability. The glamorization of drug use, of dropping out of the rat race of work and career, and of youthful rebellion against authority, self-control, and even rationality undermined traditional self-reliant, self-improving American virtues. Though the elites, shocked at how self-destructive their countercultural fling proved, soon returned to stable marriages and hard work, those at the bottom of the social ladder—disproportionately minority and poor both in income and in social capital—became an intergenerational underclass, suffering from a toxic brew of social pathologies, from school-leaving, unmarried childbearing, and welfare dependency to drug addiction and violent lawbreaking. No sooner had we righted a great wrong against black Americans, in other words, than we set a minority of them up for failure, suffocating them with our good intentions and supposed cultural liberation.

“Before workfare, one in seven New Yorkers lived on the dole. Two decades later, only one in 28 lived on welfare.”

Still, most Americans recognized that our society had zealously turned itself inside-out to better the condition of our black fellow citizens, with epochal success for most. That’s why policymakers like Wisconsin governor Tommy Thompson and New York mayor Rudolph Giuliani, along with welfare commissioner Jason Turner—who served under both men—and pundits like Thomas Sowell, Charles Murray, and me could get a hearing when we said that there was no reason that all black Americans shouldn’t live normal American lives rather than being marginalized dependents on public assistance. We got plenty of blowback, but nevertheless our views prevailed, so that even President Bill Clinton, having vetoed welfare reform twice, had to sign it into law in 1996, after Turner and Thompson had spectacularly shown in Wisconsin that work works. Before workfare started in Gotham, one in seven New Yorkers lived on the dole. Two decades later, only one New Yorker in 28 lived on welfare.

But even more dramatic than the startling shrinkage of the welfare rolls were the stories that workfare participants told of how the program had turned their lives around, so that they really did begin to see that the promise of America was a promise to them, too. They saw that they could fulfill their lives and discover and use their talents, not waste them. That was one more step in the liberation of our minority fellow citizens—and an indication that policy can sometimes change culture, rather than vice versa.

Though I didn’t join in the astonishing shout of joy that exploded from almost every window in my ultra-blue Manhattan neighborhood when the TV networks declared that Barack Obama had won the presidency in 2008, I was hardly alone among those who had voted against the graceful young senator but who nevertheless felt an irrepressible thrill at his landmark victory, thinking it eloquent confirmation that American public life had moved beyond race. But the new president, with plenty of help from the sidelines, promptly dragged the country back into the racial swamp.

Though Obama had declared in his widely acclaimed 2004 Democratic Convention keynote speech that we were one United States, not a fractious confederation of mutually resentful tribes, he forcefully denied that he had meant that “we have arrived at a ‘post-racial’ politics or that we already live in a color-blind society” in his 2006 tract, The Audacity of Hope. From the moment he arrived in the White House—with his wife declaring that the only time she’d been proud of America was when her husband won the presidency, and with his racist pastor’s “God damn America” ringing in the nation’s ears—a keynote of Obama’s presidency was his administration’s obsessive hunting down of usually imaginary racism in every corner of American life, from law enforcement and school discipline to local zoning codes and voter-ID regulations. This obsession penetrates even to the lowly reaches of the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, which forbids employers from conducting drug tests after an accident, lest they turn up too many drug-impaired minorities—making you wonder if the administration understands the difference between normalizing minority misbehavior and fighting racism. In a symbolic end of the civil rights movement, Obama watered down workfare toward the end of his first term.

On race, as on other matters, Obama’s mind can look like the sock drawer of someone too busy to junk those with holes in them or that don’t match or no longer fit. As expressed in two books, in speeches from his first campaign on, and in four farewell interviews with Atlantic scribe Ta-Nehisi Coates last autumn, the president’s racial views are both tendentious and mutually contradictory. Though race relations in his generation are much better than formerly, Obama notes, nevertheless centuries of slavery, Jim Crow, and racism have left marked gaps between black and white Americans in income, education, and wealth. So while “better is good,” and to reject angrily America’s recently extended hand of friendship is “to become your own jailer,” there’s still room for defiant black anger at the inherited inequalities that remain. Skating over the logical conclusion that those inequalities, to the extent they exist and whatever their genesis, must naturally lead to unequal outcomes, Obama espies discrimination whenever there isn’t proportional representation of blacks in any department of American life—as if all men were equal not only in rights but also in talents, tastes, energy, and virtue.

In Obama’s view, it is government’s duty to fix all this by vigorously enforcing the antidiscrimination laws to ensure that “Jamal and Johnny [are] treated equally,” which will greatly reduce disparate outcomes—hence the administration’s obsessive inquisition to sniff out discrimination wherever it skulks. Further, because the federal government once instituted supposedly universal programs, such as Social Security or the GI Bill, that actually benefited white much more than black Americans (especially since Social Security originally excluded such predominantly black occupations as domestic or agricultural work), Washington should now inaugurate universal programs, such as early-childhood education, higher minimum wages, and Obamacare, that—in fact, if not in theory—benefit minorities more than whites. Minorities, after all, make up a disproportionate share of those lacking health insurance. And once government has created a whole generation of blacks with solid educations, college diplomas, and decent jobs—and black college girls start “meeting boys who are their educational peers”—then “we’d have more family formation,” and the racial gaps in American society would narrow and ultimately disappear. You can’t have a more grandiose fantasy of the power of government social engineering than this.

Too many minority Americans are in prison, Obama repeatedly charged, pointing out that blacks and Hispanics, only 30 percent of the U.S. population, account for half the prisoners. Missing from his “disparate-impact” account is the uncomfortable fact that black Americans commit murder at eight times the rate of whites and Hispanics combined. To take a similar example, black New Yorkers, 23 percent of the city’s population, commit two-thirds of its violent crimes. So cops hassle too many blacks, according to Mayor Bill de Blasio? That’s because Mayor Rudy Giuliani decided that minority New Yorkers deserve the fundamental civil right of being safe in their homes and streets, so cops would restore law and order to their neighborhoods. And as for black crime being a legacy of slavery and Jim Crow: while the black crime rate has been slightly higher than the white rate as far back as official records go, the explosion in black criminality began only around 1964. So simple chronology makes my explanation of ghetto social pathology more plausible than Obama’s.

An insufficiently heralded consequence of the campaign for a safer Gotham: as crime, especially violent crime, declined precipitously, with murders down 85 percent from 1990 to 2015, the city’s jail population fell by 45 percent and New York State’s prison population fell by a quarter—meaning that activist policing really did change behavior. What’s more, the racial climate sharply improved when New Yorkers stopped worrying that any black youth could be a potential mugger—after they stopped reflexively feeling relieved, as Jesse Jackson once described his own emotions, to find that the footsteps behind you on a dark street belonged to a white rather than a black. Contrast New York City’s race-relations thaw to the bitter racial animosity you feel radiating everywhere in Chicago, where demoralized police have been looking the other way when they see minor criminality or kids who might be carrying guns, sending the message that not even the authorities care whether you break the law. The skyrocketing crime rate—currently, one shooting every two hours—goes hand in hand with the mutual suspicion between the races that you feel in that city every day.

If Obama saw in school-discipline data “evidence of black boys being suspended at substantially higher rates than white boys for the same behavior,” as he claimed while mandating fewer suspensions, he obviously was not examining the numbers as clear-sightedly as City Journal’s Heather Mac Donald. No, the behavior is not the same. If black boys aged 14 through 17 commit murder at ten times the rate of Hispanic and white boys combined, Mac Donald reasonably asks, is it likely that their classroom behavior is any less disproportionately unruly? Since the Obama administration’s anti-discipline edicts, student assaults on St. Paul, Minnesota, teachers have tripled. (See “No Thug Left Behind,” Winter 2017.) Seattle, which, in compliance with administration diktats, has cut school expulsions by 77 percent from 2013 through 2016, now has seen several students murdered, plus an alleged gang rape. Teachers from Gotham to Des Moines to Fresno are up in arms over Washington’s anti-discipline push, which their unions say has produced classroom anarchy.

Similarly, it was hard to follow the administration’s reasoning when it claimed that the requirement to show ID, simple prudence when it comes to boarding a plane or entering a New York office tower, becomes racism when it comes to voting. Since the right to choose one’s representatives—representatives, not redistributive rulers—is the defining prerogative of American citizenship, surely its protection calls for prudent vigilance. As for local zoning, can anyone believe that a black surgeon or banker can’t buy a house next to white surgeons and bankers in Westchester or Nassau or Loudon Counties?

Nevertheless, at the end of his presidency, Obama was still harping on the same themes. Despite all the real progress America has made, he said five weeks before leaving the White House, “we have by no means overcome the legacies of slavery and Jim Crow and colonialism and racism”—and “those who are not subject to racism can . . . lack appreciation of what it feels to be on the receiving end of that.” Just imagine what Booker T. Washington, whom the rage of real racists prevented from joining Theodore Roosevelt for a second dinner at the White House, would have said had he served two terms as president of the United States. Or Martin Luther King. Would he not have said, from the bottom of his heart, that he and his fellow black Americans truly were free at last? And might that assurance not have allowed all black Americans to seize the dream that Founding Father Alexander Hamilton, also a founder of the New York Manumission (that is, antislavery) Society, had for all Americans: that they would live in a land that let everyone discover and make the most of every talent that lay within him, for his own betterment and that of the nation’s?

Obama, whose Kenyan father abandoned him at babyhood and whose left-wing, here-today-gone-tomorrow white mother never made him her first priority, had his own personal reasons for feeling resentment, but he found a ready-made, conventional channel for expressing and redirecting those feelings in the racial resentment he learned from his only black classmate at his fancy Honolulu prep school—one of the first black kids he had ever met. (See “The Obama Tragedy,” Summer 2016.) The brittle resentment that sometimes crackled like static when Obama spoke is an emotion that economist Thomas Sowell predicted more than a quarter-century ago would bedevil college-educated blacks under the reign of affirmative action. With too few well-prepared minority applicants to go around, Sowell foresaw, the top colleges would get the best, whose SAT scores would nevertheless be among the lowest in the incoming freshman class, and less prestigious colleges would have to make do with still less prepared students, so that the mismatch between the scholastic aptitudes of incoming minority freshmen and their white classmates would be as great in second- and third-tier colleges as in the top schools—or even greater.

The disconnect between the ability and preparedness of white and minority students that affirmative action would create, Sowell feared, inevitably would confront black students with an unappealing choice: either they could “accept the prevailing standards and lose their own self-respect,” or they could “retain their self-respect by continually attacking, undermining, and trying to discredit the standards that they do not meet, scavenging for grievances and issuing a never-ending stream of demands and manifestoes”—by far, the more palatable alternative. And, of course, many more of them would fail than if they had attended colleges suited to their aptitudes.

Also inevitable, Sowell prophesied—noting that leading black educators had expressed the same worries 20 years earlier—would be a backlash from white students and a worsening racial atmosphere on campus. This friction—similar to campus contempt for “dumb jocks”—is by no means a legacy of slavery or Jim Crow, as Obama suggests, but something new, the result of misguided attempts to right those horrendous racial wrongs. In some part of himself, Obama knows this, as is clear when he writes about his wife’s feelings about her rise from an admirably close and nurturing working-class family on Chicago’s South Side, through selective public schools, to Princeton, where she starred on the basketball team, and then on to Harvard Law School and a job at a high-powered Chicago corporate law firm. Deep inside, Obama writes, “she knew how fragile things really were, and that if she ever let go, even for a moment, all her plans might quickly unravel.” That’s affirmative action’s curse upon talented minorities: you are never sure how much your achievements rest upon merit and how much upon the caprice of positive discrimination, and so you are bound to think that what might have been arbitrarily given can be just as arbitrarily taken away.

But in the years after the Obamas graduated, a strange dialectic, growing out of another impulse that Sowell had seen as inherent in affirmative action, gathered momentum and transformed colleges fundamentally. All the effort by minority students “to discredit the standards that they do not meet,” all their “scavenging for grievances and issuing a never-ending stream of demands and manifestoes,” certainly sparked the occasional mild, if ugly, racial backlash and doubtless some unspoken resentment. But the chief response, from students, faculty, and a growing army of deans and assistant deans of diversity, has been a cringing, self-abasing concern to show hearts unspotted by any stain of racism—or any supposedly analogous (but increasingly recondite) form of discrimination. Academic and critical standards are just bulwarks of race and class (and now sex) hegemony? Out they go! The accumulated wisdom of mankind about what constitutes the good life, acquired through experience and reflection, and passed down in the great works of the literary and philosophical canon, is just another “perspective”—indeed, the increasingly devalued perspective of dead white men? Let’s bring in other “perspectives,” equally valid, since we are in the realm of value, not fact, and therefore (goes the current cant) all judgment is relative, appropriate to the circumstances out of which ideas and values arise, none better or worse than any other. History—being just a record, as Obama puts it, of slavery, racism, and colonialism—has nothing to teach us about what kind of government or social system allows the freest, most prosperous lives, so why learn about the Founding Fathers’ struggle to create a self-governing republic—slave ownership fatally discredits them—and why bother to know in which 20-year time period nearly 400,000 Union soldiers died to make men free (as, according to the American Council of Trustees and Alumni, one-third of the graduates of the nation’s top 50 colleges and universities don’t know)?

That scavenging for grievances that Sowell foresaw reached its logical but risible conclusion in the campus discovery of “microaggressions,” racist words or acts so infinitesimal that only the offended minority can discern them, while the oblivious white offender, as Obama put it, must, because of his race, necessarily “lack appreciation of what it feels to be on the receiving end of that.” (See “The Microaggression Farce,” Autumn 2014.) On campus nowadays, no matter how innocent your intended meaning, if a minority denounces what you say as racist, you can be hounded out of your job, as were Yale faculty members Nicholas and Erika Christakis. Or you can be disciplined by the diversity apparatchiks for “hate speech.” What makes this development even scarier is that what starts on elite campuses often grows to maturity in the larger world—meaning that people have lost their jobs for speech that supposedly creates a “hostile workplace climate”—and that the First Amendment is in danger.

Similarly, the Black Lives Matter movement—spawned on campuses and in rectories across the nation, and fertilized by George Soros’s money—has spread the falsehood that America’s cops are the shock troops of a fundamentally racist nation, which licenses, even silently encourages, them to kill blacks. The result: a spike in cop killings by deranged blacks; unrelenting U.S. Justice Department and mainstream media scrutiny of scores of police departments, resulting in police unwillingness to risk their careers by intervening to stop trouble before it starts; and a rise in murder and other violent crime in more than two dozen U.S. cities in the first half of 2016, on top of a 10.8 percent jump in murders nationwide in 2015. Big lies, as history shows, have big real-world consequences.

So while a people’s whole history leaves its traces on their culture and therefore on their subsequent fate, what we are seeing in post-Obama American race relations is not the legacy of slavery and Jim Crow but rather the consequences of the world-historical civil rights movement’s excesses and errors, which by no means outweigh its success. But there is one further twist to the story. Or even two.

Every summer, most colleges require their newly admitted students to read some left-wing bestseller, in order to start their political indoctrination through freshman-week discussions. For some years, the text was Barbara Ehrenreich’s screed against menial labor, Nickel and Dimed, which, in the age of Trump, looks even more snobbishly out of touch. This past summer, it was the drearily turgid Between the World and Me, by Ta-Nehisi Coates, Barack Obama’s interviewer in his farewell Atlantic articles.

A keynote of Coates’s book is the author’s youthful contempt for the civil rights movement, an angrier version of Obama’s affectionate condescension toward his mother’s civil rights “sentimentality.” As a teenager, Coates hated February’s celebration of Black History Month, when his teachers herded him and his classmates into the auditorium to watch “films dedicated to the glories of being beaten on camera”—as if black people should love the dogs and tear gas and fire hoses that police let loose on them, the curses and worse that the Southern mobs showered upon them. “Why were only our heroes nonviolent?” he wondered. Wasn’t that undignified, unmanly? And doesn’t it make blacks complicit in their own oppression by whites, who are always “quoting Martin Luther King and exulting nonviolence for the weak and the biggest guns for the strong”?

“That’s affirmative action’s curse: you are never sure how much your achievements rest upon merit.”

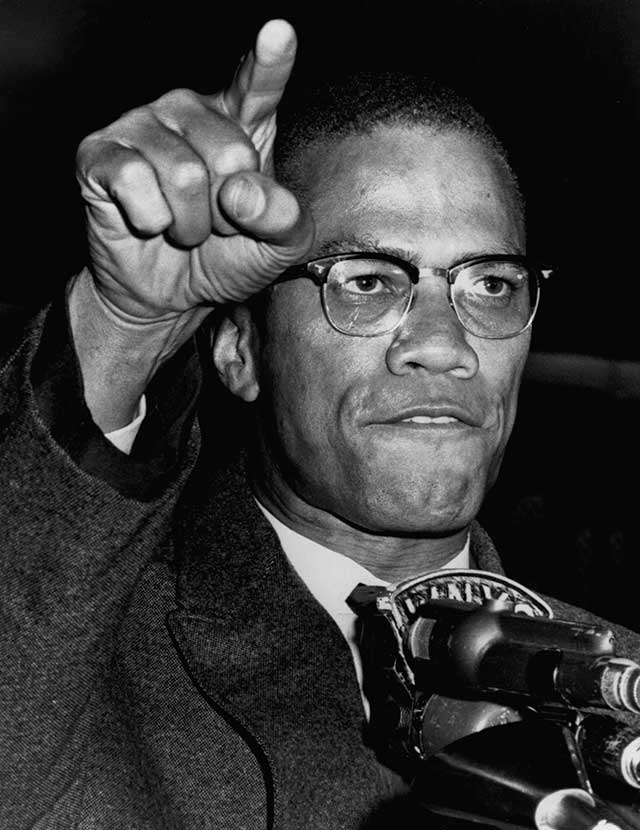

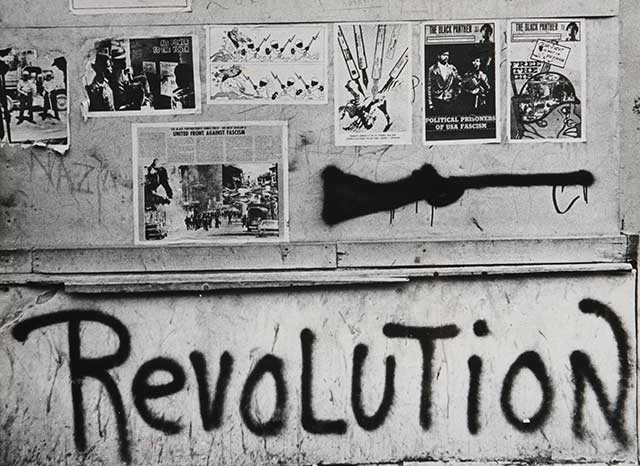

Much better, in Coates’s opinion, is the example of Malcolm X, the charismatic, radical Black Muslim leader, famously photographed in Ebony holding an assault rifle and peering out a window for the assassins he feared sought to kill him on orders of a rival—as one did in 1965. Rejecting the civil rights movement’s embrace of nonviolence and integration, Malcolm preached Black Power, black superiority, black separatism, and resistance “by any means necessary,” including violence, to racist oppression. “If he was angry, he said so. If he hated, he hated because it was human for the enslaved to hate the enslaver,” Coates writes. “He would not turn the other cheek for you” but rather “spoke like a man who was free.” The year after Malcolm’s murder, the Black Panther Party, the icon of sixties radical chic, with their assault rifles and military berets, arose in California, seemingly from Malcolm’s grave and preaching his gospel of black power and armed resistance (especially to police), until those few Panthers who weren’t killed in shootouts with government authorities declined into mere thuggery.

Coates’s father had been a Black Panther captain, as well as a Howard University research librarian, always looking for a glorious, usable African history for black Americans to assert proudly—and which Malcolm claimed existed—as a counter to racist claims of their inferiority. It was into that Malcolm-inspired tradition that Coates was born, though only recently, and very reluctantly, did he come to realize that such a history was largely fantasy, just as he came to see, late and grudgingly, that the civil rights movement embodied a realistic understanding that Black Power was also a chimera, for no amount of posturing with guns would intimidate white America; and finally, only an appeal to its conscience and its ideals, as set forth in the Declaration of Independence, could effect racial justice.

This indigenous streak of violent black antiauthoritarianism and cop hatred, another of those “seeds planted in the 1960s,” as Coates puts it, was a critical ingredient in the making of the inner-city underclass—one that I had insufficiently noted in my account of how the culture of the sixties created that underclass in The Dream and the Nightmare. Its influence extended far beyond the underclass, as it turned out. The Autobiography of Malcolm X, Obama writes, was the key text in teaching him how to be black. Coates, who as a high school student listened over and over again to the early rap anthem “Fuck tha Police,” points out that hip-hop lyrics began quoting Malcolm X in the 1990s and have ever since been popularizing his antinomian worldview to an increasingly wide, even global, audience—along with, I would add, the gross male supremacism that the early Black Panthers spewed. Much is made of the black contribution to American music: this is one we could do without.

The end result of all these cultural changes—which are not an organic development but rather the fruit of a propaganda push that extends from President Obama down to the rap music celebrities whom he counts among his friends and who turned up often at his White House parties—is that most young Americans are as oblivious to the civil rights movement as they are to the Civil War. Abraham Lincoln so movingly urged at the cemetery on the blood-soaked Gettysburg battlefield “that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain”—and “that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion.” They did not die in vain—any more than those assaulted in Birmingham, Alabama, during the civil rights movement suffered in vain. The slaves were freed; civil rights came to all. But too many black Americans today don’t know about all those great sacrifices, and certainly don’t know that they pried open the doors of opportunity for them and put success within their grasp, if only they’d seize it. That achievement has been erased from history. “He who controls the past controls the future,” George Orwell wrote in 1984. “He who controls the present controls the past,” he added—to the detriment of our black fellow Americans, as we have seen these last eight revisionist years.

Top Photo: “Creative protest,” urged Martin Luther King, Jr., from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in August 1963, must not “degenerate into physical violence.” The civil rights movement must meet “physical force with soul force.” (AFP/GETTY IMAGES)