In December 2022, California’s nine-member Reparations Task Force, formed by Governor Gavin Newsom two years earlier, estimated that, if a reparations program were ever adopted, each black person in the state descended from slaves could receive as much as $223,200 in compensation for past injustice. The projected total cost, to California taxpayers, could reach $569 billion—almost two and a half times the state’s current budget. The task force is due to give its final recommendations in June 2023, including the exact monetary amount of compensation. “We are looking at reparations on a scale that is the largest since Reconstruction,” said one task-force member.

And yet: California was never a slave state. It entered the Union as a free state in 1850 after its acquisition from Mexico, which had banned slavery in 1837. So the task force, while dictating that only descendants of slaves can receive payouts, has focused on housing discrimination that took place between 1933 and 1977, a period beginning 68 years after slavery was abolished in the United States. But this is just a baseline. Other areas—mass incarceration, forced sterilization, unjust property seizures, and devaluation of businesses—might warrant “future deliberation.”

Lawmakers in Democratic-controlled states such as Maryland, New Jersey, New York, and Oregon have similarly introduced (or hoped to revive) proposals to study reparations; so far, only California has successfully advanced the cause. Its work could become a model not only for other states but also for a federal reparations plan. Meantime, San Francisco has introduced its own reparations initiative and has proposed a $5 million payment to each black resident.

California Democrats’ intention to pursue racially targeted financial payouts could prove politically risky. Recent polling shows that only 30 percent of Americans support the concept of financial reparations for descendants of enslaved people. But support for the initiative is divided along racial lines. Seventy-seven percent of black adults say that descendants of American slaves should be repaid in some way, while only 18 percent of whites, 39 percent of Hispanics, and 33 percent of Asians agree. Support for race-based reparations also skews heavily by political affiliation. Voters who lean Democrat are split on the issue, with 49 percent in opposition and 48 percent in support; nearly 91 percent of voters who lean Republican are opposed. One could see the reparations effort, then, as a strategy for locking the black vote to the Democratic Party forever.

The fundamental concept of reparations depends on the idea that the United States should recognize and admit the wrongs that it has committed against black Americans and that those who benefited from those wrongs must acknowledge the advantages they’ve gained as a result, offering compensatory damages to the descendants of those who suffered. But with California history lacking any specific link to slavery, the task force struggled to monetize a payout figure. Thus, it details historical accounts of racially discriminatory practices in 1933–77 to estimate the approximate amount of black wealth lost. The task force argued that black Californians lost $5,074 per year under previous housing policies, bringing the estimated financial reparations for slavery to $223,200 per person.

The practice of racially restrictive covenants, also known as redlining, often played a role in purchase and sale contracts during this era, affecting entire neighborhoods—most often by way of deed restrictions established locally throughout various counties and municipalities. The task force’s recommendations are ahistorical, however, and single out blacks as victims when, in fact, many people faced housing discrimination during that period: Native Americans, Latinos, Asian-Americans, Jews, and other minorities. Further, past housing discrimination does not fully explain present-day racial disparities in wealth or income. Asians have experienced far worse housing discrimination than blacks in California, yet Asians have much higher incomes and more assets. Japanese-Americans were legally prevented from owning land and property in more than a dozen states from 1913 to 1952, and more than 100,000 were placed into internment camps during World War II, largely located in California. Today, Japanese-Americans outperform whites by large margins in education achievement and income: they have the highest median net worth ($592,000) in the Los Angeles metro area, followed by Asian Indians ($460,000) and Chinese ($408,200), all outranking white households, which have a median net worth of $355,000. Mexicans and U.S. blacks have a median net worth of $3,500 and $4,000, respectively.

Someone from another country following the task force’s work might conclude that America is composed of only blacks and whites, with no other races or ethnicities. Other minority groups, such as Latinos and Asians, greatly outnumber blacks. In California, according to the 2020 Census, 39 percent of state residents are Latino, 35 percent are white, 15 percent are Asian-American or Pacific Islander, 5 percent are black, 4 percent are multiracial, and fewer than 1 percent are Native American or Alaska Natives. Though no race or ethnic group constitutes a majority of California’s population, Latinos surpassed whites as the state’s largest ethnic group in 2014.

Another major flaw, from a Latino perspective, is the task force’s limited focus on redressing wrongs affecting only blacks—thus ignoring major events in California history with relevance to the grievances of Mexican-Americans, starting with conflict over lands annexed from Mexico after the U.S.–Mexican war and the many discriminatory situations that Mexican-Americans faced afterward, in the twentieth century. Mexican-Americans were widely scapegoated during the Great Depression for the nation’s poverty and unemployment. From 1929 to 1936, the Mexican Repatriation forcibly deported an estimated 2 million people of Mexican ancestry to Mexico; nearly 1.2 million were legal citizens, born in the United States.

One could argue, then, that if California were to make financial reparations to any one group, black Americans would not be in the top position to demand such payouts. Latinos and Asians would likely have stronger historical claims. Herein lies the fundamental problem with reparations: the lineage of victimhood will never end. Why not go back, further, skipping over Latino and Asian claims, and pay reparations first to Native Americans? California’s plan to offer reparations only to black Americans seems likely to create more racial antagonism among minorities.

The reparations commission’s report not only tries to make the case for racism as a pervasive tool of white supremacy, affecting blacks in all aspects of modern life; it also aims eventually to expand the concept of reparations into areas such as education inequality, political disenfranchisement, mass incarceration, housing, and health outcomes. The task force’s preliminary recommendations include:

- Eliminate discriminatory practices in standardized testing, inclusive of statewide K–12 proficiency assessments, undergraduate and postgraduate eligibility assessments, and professional career exams such as SAT, MCAT, and even the state bar exam.

- Establish a state-subsidized mortgage system that guarantees low interest rates for qualified black mortgage applicants. The program would not be extended to members of any other minorities or racial groups.

- Repeal the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation statute requiring “every able-bodied prisoner imprisoned in any state prison as many hours of faithful labor in each day and every day during his or her term of imprisonment as shall be prescribed by the rules and regulations of the director of Corrections.”

- Forgive past-due child-support payments owed to the government by “noncustodial parents.” A noncustodial parent is one with whom a child does not live full-time—typically, fathers. This would essentially let deadbeat dads off the hook, with the government now responsible for the father’s children.

The task force’s recommendations appear to ignore (or override) the California Civil Rights Initiative, which declares: “The state shall not discriminate against, or grant preferential treatment to, any individual or group on the basis of race, sex, color, ethnicity, or national origin in the operation of public employment, public education, or public contracting.” The report’s long list of policy demands clearly makes race the central determinant. For this reason, many dismiss the demands as impractical and unachievable—not to mention unconstitutional. But the timing of the final report will elevate reparations as a major issue for the 2024 election, one likely to bring out black voters in force and perpetuate their alliance with the Democratic Party.

Yet, regarded as a negotiating ploy, the underlying strategy is ingenious. Even if the entire package isn’t adopted, more achievable demands might be considered—and these might even be the ulterior motive.

Giving incarcerated felons the right to vote is a good example. The report argues that extending voting rights to incarcerated persons serving felony sentences is necessary in order to end modern-day forms of legal slavery in California. The report notes that blacks account for nearly 28 percent of inmates in the state’s prison system, despite being only “about 6 percent” of the state’s population. Making no reference to blacks’ rates of criminal offending, the task force simply labels this discrepancy a manifestation of institutionalized racism.

California already provides criminals with more voting rights than other states. Convicted felons in California lose their right to vote when they’re incarcerated in state or federal prison, but it’s automatically restored upon completion of their sentence, even while on post-release supervision or probation. In Florida, by contrast, which has some of the stricter laws nationally, a felony conviction of moral turpitude—involving murder or sexual abuse—will result in the permanent loss of voting rights, which can be restored only by a formal pardon from the governor.

Letting incarcerated felons vote (they would go heavily Democratic) would have political implications, especially in states where ballot-harvesting is legal, such as California. With approximately 147,000 California residents locked up in state or federal facilities, felon voting is a ballot-harvesting dream—and one that could significantly disrupt electoral districts that include state prisons, if prisoners can register to vote in the districts where they are incarcerated. In fact, many of the state’s prisons are in rural areas of the Central Valley, which lean Republican. Take, for example, California’s 13th Congressional District, where Republican congressman John Duarte won by fewer than 600 votes. The district has two state prisons, with a combined population of more than 5,000 inmates. One can envision a scenario in which prisoners become a coveted voting bloc that can flip red districts blue.

The United States has the highest incarceration rate in the world, with nearly 2 million people behind bars at any given time. If the report’s recommendation of voting rights for imprisoned felons became a national model, it would represent a major political win for Democrats.

For all its problems, the report is not without merit—it calls out the state’s failing public education system, especially for low-income minority children, a civil rights issue that deserves far greater outrage than it receives. The state’s latest test scores show that nonwhite children are performing dismally in reading and math. Seventy percent of black children and 64 percent of Hispanic children do not meet state reading standards. Math scores are even worse, with 84 percent of black students and 79 percent of Hispanics not meeting state standards. Access to quality education is foundational to achieving the American dream, yet California children are educationally redlined into their local zip-code-determined schools, even when state officials know that these schools are failing. Too many policymakers respond to the dismal school performance only by calling for greater funding. More money is not the answer: California spends $15,837 per K–12 pupil, ranking 19th among the 50 states and Washington, D.C., but it ranks 44th out of 50 academically. The state’s education code includes tenure and dismissal statutes that make it virtually impossible to terminate failing teachers.

The task force commendably calls for the creation of porous school-district boundaries that allow students from neighboring districts to attend; it also supports more interdistrict transfers, so that students can attend public schools based on factors independent of their parents’ income level and ability to afford housing in a particular neighborhood or city. Of all the recommendations in the report, these would perhaps make the biggest impact on bettering the lives of black kids—yet they are also steps that could be taken immediately, with no reparations needed.

If Governor Newsom really wanted to better the lives of nonwhite children, he could support educational choice—whether in the form of opportunity scholarships, vouchers, charters, or all-district admission policies. Working-class minorities tend to support such policies. Public schools remain dominated by failed and self-certified public-sector unions; Newsom’s refusal to challenge underperforming schools in minority areas is suggestive of his unwillingness to challenge the California Teachers Association, the most potent force in California politics. The CTA’s overflowing campaign coffers helped Newsom defeat a 2021 recall effort. He will need CTA support if he pursues national office.

California is facing a potential $23 billion budget deficit, driven largely by high inflation, rising interest rates, and a drop in revenue due to fears of a national recession. The Reparations Task Force’s recommendations of $569 billion in state payouts would financially bankrupt California—but embracing some form of reparations could also pave the way for Gavin Newsom to replace Joe Biden as black America’s preferred Democratic presidential candidate. Despite Newsom’s protestations that he is not running for the presidency, he understands the race game and the black vote’s centrality to Democratic success—particularly for a white candidate in a party that has increasingly demonized whiteness.

Martin Luther King envisioned America as a land of equal opportunity for all, not one of government-enforced equal outcomes or perpetual victimhood of the “aggrieved” at the hands of the “oppressors.” But if reparations advocates get their way in California, every policy failure of the state will be blamed on slavery. Those who never engaged in slavery will carry the burden of making amends for it, and those who didn’t suffer from it directly will benefit. The Democratic Party now views too many issues through the prism of historical race and gender oppression; it rejects equality of opportunity in favor of a hierarchy of privileges for identity groups ranked according to their levels of alleged historical mistreatment.

The desire of many Democrats to offer slavery-based financial reparations to blacks alone comes with risks to its own prospects—including in California, a state where ethnic minorities constitute the majority. The reparations push risks marginalizing and taking for granted other minorities, including some, like Asians and Latinos, that are becoming more “unwoke.” It was Asian-Americans in San Francisco, after all, who ensured the recall of progressive district attorney Chesa Boudin. And nationally, Latinos have emerged as a significant voting bloc capable of flipping blue seats red, driven by education and public-safety issues. Still, with the nation confronting an unstable economy, an open-border crisis, spiraling crime in major cities, and pervasive failure and instability in public education, Democrats have few domestic policy issues to run on in 2024. Perhaps they calculate that the promise of direct cash payments and financial incentives to the most loyal element of their voting base is a price worth paying—even one this high.

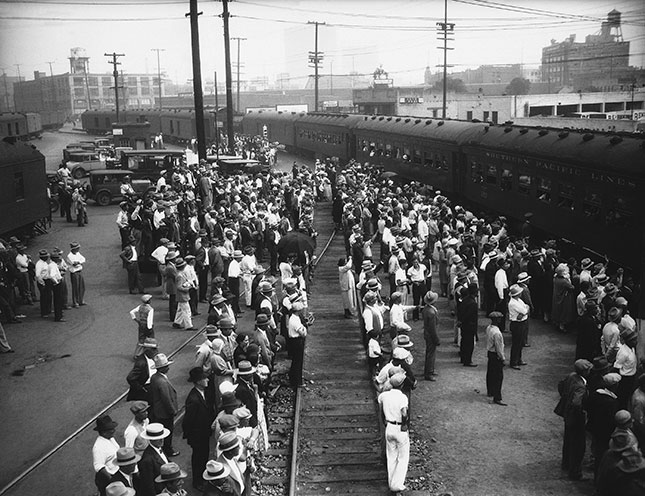

Top Photo: Due to give its final recommendations in June 2023, the task force is “looking at reparations on a scale that is the largest since Reconstruction,” according to one member. (RICH PEDRONCELLI/AP PHOTO)