The president took the oath of office facing an “economic Dunkirk,” as his top advisors warned. The unemployment rate was 7.5 percent, up from 5.6 percent 18 months earlier. In his inaugural address, the president acknowledged that America was “confronted with an economic affliction of great proportions,” and he resolved to “begin an era of national renewal.” The job would take time, he said: “The economic ills we suffer have come upon us over several decades. They will not go away in days, weeks, or months.” But more than a year later, Americans were still waiting. Critics, including some from his own party, complained “all over the airwaves with proposals which are impossible to realize,” the president wrote privately. Unemployment rose to double digits, hitting 10.8 percent on the eve of the president’s second anniversary in office. Midterm election returns—a referendum on his first two years—were disastrous. Time reported that the president’s “economic advisers have been emptying out their desks and leaving,” underscoring “an impression of disarray within the Administration’s top economic ranks.”

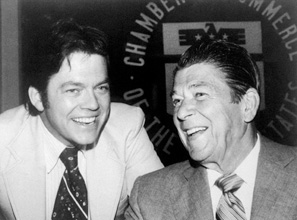

President Barack Obama in early 2011? Nope: President Ronald Reagan in late 1982. Yet two years later, Reagan won reelection in a landslide. The famous Reagan campaign ad that proclaimed a “Morning in America” could trumpet a powerful new statistic: “Today, more men and women will go to work than ever before in our country’s history.” Unemployment was still at 7.2 percent, but it was falling. “Why would we ever want to return to where we were less than four short years ago?” the ad asked. The theme was a winner because the question was so obviously rhetorical. During Reagan’s second term, unemployment would bottom out at 5.3 percent.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

Three decades after leading the nation out of malaise, Reagan can lead once again, this time through the example of the four pillars of his original campaign—taming inflation, cutting taxes, spending government money on the right things (in his case, defense), and balancing the budget. The Gipper didn’t achieve all those goals, and President Obama and Congress would need to adapt his example to a different time, of course. In fact, Obama’s job may be tougher, as history shows that recovery from a burst credit bubble is harder than recovery from other kinds of recession. But the mission is the same: economic growth. And the principle behind the four pillars also remains the same: government shouldn’t compound crisis-induced economic uncertainty by adding more uncertainty.

Almost as soon as he became president, Reagan had early opportunities to instill public confidence in the economy. During his second week in office, he ended price controls on domestic oil, which the White House had imposed since the early seventies to keep costs down; the controls had diverted global supplies elsewhere, creating shortages and long lines at the American pump. Then, that summer, the nation’s air-traffic controllers—federal workers—went on strike. “That’s against the law,” Reagan wrote in his diary. “I’m going to announce that those who strike have lost their jobs.” True to his word, he gave the strikers 48 hours to return, fired the recalcitrant, and invited applications from job-seekers. As economist Larry Kudlow, associate budget director in Reagan’s first term, observes, the president’s bold action “sent a powerful signal. Unions would not run this country into the ground.” It was a far cry from the stimulus bill of 2009, passed at a time when private-sector workers again needed a signal that well-organized government employees wouldn’t exploit the economic crisis to gain more power. The bill confirmed their worst fears, however, sending their hard-earned dollars to subsidize state government workers’ rising pay and benefits. Reagan’s energy policy was a far cry, too, from Obama’s, which was to propose new supply controls on carbon through a “cap-and-trade” program. (Congress has dropped the idea for now.)

As important as these moves were in restoring confidence, Reagan knew that setting the country on a recovery course would take more than single actions. The first pillar of his campaign was to reduce inflation, which was wreaking economic havoc. In large part because the Federal Reserve had flooded the economy with money, prices had soared by double-digit rates in 1979 and 1980, something that hadn’t happened in two consecutive years since World War I. That meant reduced consumption, since wages didn’t keep pace with those prices. Businessmen, fearing that a devalued dollar would consume any fruits of their investments, stopped putting money into job-creating projects and bought commodities instead. Savers lost money as bonds and other savings instruments shrank in value.

One of Reagan’s major allies in the battle on inflation was Paul Volcker, the Federal Reserve chairman appointed by President Carter in 1979. Just six weeks after taking his post, Volcker began to attack inflation by squeezing the money supply, making it prohibitively expensive for people and companies to borrow. This action would, in time, bring down inflation. But it would also mean a lot of economic pain first—above all, higher unemployment, as cheap credit vaporized. Industrial titans rebelled. With auto showrooms empty of customers, Lee Iacocca, the chairman of Chrysler, denounced Volcker’s strategy as “madness.” The nation’s chief homebuilders’ lobbyist accused the Fed of making mortgages unaffordable and paralyzing the housing market. Small wonder the world was dubious that Volcker, in the face of such pressure, could hold the line.

But Reagan quickly disappointed observers who hoped that he would use Volcker as a punching bag. The new president took to heart the counsel of Citicorp chairman Walter Wriston, an early candidate for Treasury secretary, who wrote in his bank’s election-month newsletter that Presidents Johnson, Nixon, and Carter had all shown “unwillingness to accord a sufficiently high priority to the slowing of inflation.” Any “vacillation in the fight against inflation” would result in political defeat, Wriston believed, adding that taming inflation was far more important than cutting taxes.

At his first press conference, President Reagan showed that he understood what needed to be done. “For all these decades, we’ve talked and we’ve talked about solving these problems and we’ve acted as if the two were separate,” he said. “So one year we fight inflation, and then unemployment goes up. And the next year we fight unemployment, and inflation goes up. It’s time to keep the two together where they belong—and that’s what we’re going to do.” Even as the Fed’s actions during Reagan’s first two and a half years in office pushed the unemployment rate to its peak, the president continued to back Volcker. With no refuge in the White House, inflation expectations disappeared, years faster than the president’s advisors had imagined possible.

Reagan’s resolute stance is instructive for our current economic plight. Beginning in the early 2000s, bad policies—in particular, the extremely low interest rates that the Fed pushed after the tech bubble burst and after 9/11—led to easy credit, seducing too many Americans into borrowing too much, often for the purpose of buying a house. Once again, monetary policy had distorted the economy, though the result this time was not inflation but a widespread overvaluing of long-term assets, such as houses, mortgages, and stocks. When the credit-expanded bubble proved unsustainable, starting in 2006, the assets’ prices began to fall. But the Fed’s strategy has been to pump yet more money into the financial system, trying to reinflate housing and other asset prices, rather than deal with the aftermath of another round of losses.

The economy will continue to have trouble recovering while it remains distorted by too much money. Just as inflation induces paralysis by obscuring what goods and services are worth, still-overvalued assets keep people and businesses—fearful that investment values will fall when the government’s unprecedented support goes away—from making the long-term investments that the economy needs to grow.

In fulfilling his second campaign pledge—cutting taxes—Reagan sent clear, direct signals to the marketplace. Savers, workers, and business leaders had enough to worry about, the president reasoned, without having to add tax-policy confusion to their concerns. So his tax law was a model of simplicity: it would slash taxes by 25 percent over three years, and it would do so not through a confusing array of tax credits and sweeteners but by reducing tax rates across all income groups. (Republican congressman Jack Kemp of New York had advocated such a plan for several years.) With rates falling from as high as 70 percent, everyone who made more would keep more. To spur stock-market investment, Reagan slashed taxes on capital gains, too, from 28 to 20 percent. And the president indexed income brackets to inflation, so that future monetary malpractice—say, policies that resulted in extreme inflation, driving up salaries with artificially weak dollars—wouldn’t result in government confiscation of earnings.

Reagan took his playbook from academics, but his philosophy was rooted firmly in experience. He listened to Art Laffer, an economist who argued that lower tax rates, in some cases, could produce more growth and hence more revenue for Washington. As the governor of California, Reagan had been a traditional fiscal hawk, dedicated to balancing budgets either by reducing spending or by raising taxes, notes Laffer today. But “Reagan really flipped in his life,” Laffer says, and embraced what became known as “supply-side economics” partly because he realized that the policy would have worked in his own life. He was fond of recounting how, as an actor after World War II, he limited himself to making four pictures a year—because a fifth would throw him into what was then a 91 percent top tax bracket, making additional work not worth the trouble.

Reagan’s tax reform changed a generation’s worth of thinking on tax policy. For more than a decade before he took office, policy wonks and politicians had viewed tax policy as just another tool that Washington could use to manage economic ups and downs. Tax cuts should work to stimulate a flagging economy, many thought, but could also add to inflation and thus should be carefully targeted. Volcker, for example, warned that the Reagan tax cuts would result in inflationary pressure, and Lester Thurow, a prominent economist, said that the economy “certainly cannot take anything like this amount of economic stimulus without exploding.” Reagan, by contrast, thought that tax cuts should be broad, helping people and companies plan their work and investments more easily. A less firmly grounded president might have let conventional economic expertise carry him away. But Reagan stuck to his guns, and the economy did fine. After shrinking 1.9 percent, after inflation, between 1981 and 1982, it grew by 4.5 percent in 1983 and 7.2 percent in 1984. And it kept growing steadily through the end of the decade.

During Reagan’s second term, the White House pursued a different kind of tax reform. In 1984, ahead of reelection, Reagan directed Secretary of the Treasury Donald Regan to design a plan that would eliminate loopholes and special tax breaks, thus allowing even lower taxes on personal income. The point was not for Washington to gain or lose money. The nation would build a more efficient economy, as individual citizens and investors put money into the ventures that they deemed most useful, rather than following the government’s determination, say, that investing in an oil well deserved a tax credit but investing in a tech start-up didn’t. As veteran political reporters Jeffrey Birnbaum and Alan Murray wrote in Showdown at Gucci Gulch, the Treasury worked on the reform under the assumption that “all income should be treated equally by the tax system, regardless of where it comes from, what form it takes, or what it is used for.”

The result of the two-year effort was the 1986 tax-reform law, which compressed 14 tax rates into just two: 15 and 28 percent (not counting a 5 percent surcharge on top earners). Just as important, it vacuumed out some clutter. The reform wasn’t perfect; it mostly shrank a few tax breaks, rather than killing off the worst ones. Reagan never touched the most sacrosanct of tax breaks: the deduction on mortgage interest. The state and local tax deduction, which Reagan wanted to get rid of, stayed in the code, too, as governors marshaled against any change. And Reagan eventually decided, Birnbaum and Murray point out, that “if raising corporate taxes was the only way to pay for lower [individual] rates, then so be it.”

Still, the law was a good one, and it passed Congress. The Democrats of the era were open to tax reform; Dan Rostenkowski, who controlled the House, backed it wholeheartedly, as he figured that killing tax breaks made the code fairer to people without the resources to lobby. The Senate, for its part, passed the law 97–3. The timing was key. Reagan realized that the time to iron out the tax code’s wrinkles wasn’t 1981, when the nation’s economy was still reeling, but 1986, when it had sufficiently recovered from the ordeal of the seventies to be able to digest changes.

Today’s politicians can borrow a page from Reagan’s tax narrative, using it, as he did, to address both immediate pressures and longer-term concerns. Above all, they should not keep the public uncertain about whether the “Bush tax cuts” will remain. December’s compromise, through which both parties agreed to extend the cuts for two years, failed to provide the badly needed clarity that would let investors plan for the future. Obama should thus pick off a few moderate Democratic senators and then, together with House Republicans, make today’s tax rates permanent.

In taking the offensive on taxes, Obama could gain political advantage. Though he would further anger his disenchanted base, the president would find Republicans to be enthusiastic about an about-face, while most centrist working-class voters—the ones Obama needs to secure reelection—would probably be more concerned with economic growth and keeping their own tax rates low than with making top earners’ higher. The president would find, too, that when investors know that income taxes on capital gains and dividends aren’t going up in two years, they’ll invest with greater confidence, spurring a healthier recovery and making Obama much more reelectable.

Obama should save the hard stuff for later, just as Reagan did. As Kudlow says, “the next step” would be “broad-based tax reform: get rid of all that crap.” Today’s tax code teems with special breaks—both survivors of Reagan’s purge and more recent arrivals—which cost a staggering $1 trillion annually. Last year, one of the suggestions made by Obama’s National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform was to scrap all the breaks, even the mortgage-interest deduction. But even modest reform would help Washington raise money without raising tax rates. Obama could use some of the money to pay down deficits and the rest to cut the corporate tax rates, so that we could compete better with the rest of the world. Reform could also reduce economic distortions. For instance, if Washington gradually capped the mortgage deduction at, say, twice the median mortgage-interest payment, money that’s currently flowing into housing could shift into productive investments instead.

The recovery is too weak to start this daunting job now, but it’s not too early to start thinking about reform. The president took a step in that direction in December, announcing that his Treasury was already poring over both the individual and corporate tax codes. But Obama can’t rely on his Treasury’s expertise. He also “should develop a rapport with Congress” rather than “poison the waters with hostility,” notes the Heritage Foundation’s Ed Meese, a Reagan advisor and the late president’s attorney general. Obama must learn to accept compromise graciously—which means not calling his partners in compromise “hostage takers,” as he did in announcing the temporary extension of the Bush-era cuts. Reagan-style courtesy across the aisle may be even more important today. As Jeff Bell, a Republican political consultant who helped design Reagan’s ad campaign (and former president of the Manhattan Institute), says, the parties are more polarized now on taxes, with many Democrats ideologically inflexible in opposing low rates.

Reagan campaigned on a third plank in 1980: higher defense spending. Here, the president wanted government to do more, not less. Defense spending had steadily shrunk as a share of the federal budget, from 42 percent of spending in 1970 to 23 percent in 1981. Reagan brought the military’s share of spending back up to 28 percent by his last year in office. The United States eventually emerged from the Cold War the lone superpower.

Reagan didn’t view the buildup as an economic reform. If he had, he likely would have sacrificed it to closing budget deficits; instead, he maintained that defense was more important than the budget. But securing America’s future as a great power would support private-sector growth in the long run. And he knew that defense spending provided jobs: in 1987, he wrote privately of Democratic defense-cut proposals that “they would dump a quarter of a million young men out of uniform & on the job market.”

Reagan’s defense budget offers a lesson to President Obama about why the 2009 stimulus bill—the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act—failed to convince the public that it was what its name claimed. Americans must see a compelling reason for spending more money, especially during a recession. Rebuilding American power was such a reason. But voters could perceive that Obama’s stimulus had no clear purpose. It was public spending for the sake of public spending, a fact underscored by Obama’s lack of focus on any one thing in the stimulus; instead, he let Congress jam a little bit of everything into the bill, making voters suspect—correctly—that they had gotten nothing.

It’s not too late. George Shultz, a Reagan advisor and, beginning in 1982, secretary of state, guesses that if Reagan were president today, he might prioritize infrastructure spending. After all, America’s infrastructure needs reinvestment almost as badly as its post–Vietnam War military once did. No need for an academic study to prove this to voters; people can see with their own eyes that the assets bequeathed to them by previous generations are crumbling. As the American Society of Civil Engineers figures it, the country must put $1.3 trillion over five years into its roads, highways, and bridges. Aging bridges around the country, including New York’s vitally important Tappan Zee Bridge, are in such dire need of replacement that lives are at risk.

Infrastructure reinvestment, like defense, would directly create hundreds of thousands of jobs, but that would be a side effect. The true purpose of an infrastructure plan would be safeguarding private-sector growth. If people can get to work more quickly and safely, for example, they can work longer hours; if investors feel confident that dams won’t collapse, they’ll put more money into private property.

Reagan’s fourth campaign objective was to balance the budget by 1984. Instead, annual deficits exploded, and the national debt swelled from $909 billion when Reagan took office to $2.6 trillion when he left. As a percentage of the economy, the debt rose by more than half, to nearly 52 percent. The culprit wasn’t the tax cuts. During the last six years of Reagan’s term, as the lower taxes on capital spurred investment and the lower taxes on income spurred labor, tax revenues averaged 17.8 percent of GDP—only a tenth of a point lower than they had been throughout the seventies.

No, the problem was that spending grew even faster than the economy did. Reagan had entered office gung-ho about budget-cutting. His budget director, David Stockman, would have taken an ax to everything from farm subsidies to mass transit to Medicaid. As Stockman soon discovered, though, every budget line item had a cheering section. Urban congressmen were happy to save their rural colleagues’ farm subsidies, so long as the farmers helped save their transit subsidies in return. The Cabinet wasn’t thirsting for blood, either. As Reagan wrote about Amtrak in his diary, “the case for getting Govt. out of the RR business has no opponents. Liddy Dole”—then the transportation secretary—“however does have a good argument against doing it right now.”

Critics are “too hard on Reagan on spending,” says Bruce Bartlett, who headed Congress’s Joint Economic Committee when Reagan was pursuing his economic and fiscal programs. And Reagan did win some modest budget victories; for instance, he persuaded Congress to cut grants to state and local governments by nearly 4 percent in real terms during his first year. But by 1988, those grants were 26 percent higher than they had been when Reagan took office. After just a year in the White House, a troubled Reagan wrote in his diary that “we who were going to balance the budget face the biggest budget deficits ever.” He saw the real problem: “Our deficits are structural as well as recession caused. We have a built in increase in the budget which is automatic,” largely because of entitlements—above all, Social Security and Medicare.

In the minds of his critics, the collapse of Reagan’s fourth campaign pillar was his one great failure. But the reality is that Reagan had to sacrifice one goal, and he chose wisely. He could have abandoned the military buildup by embracing Congressman Newt Gingrich’s 1982 proposal to freeze all spending; instead, he rejected the proposal, noting in his journal that “it’s a tempting idea except that it would cripple our defense program.” That wasn’t something that the nation wanted, then or now. Or he could have given up his tax program, maintaining or even raising taxes in order to balance the budget. But tax hikes can go only so high before they start to hurt economic growth. Even Stockman, one of Reagan’s fiercest fiscal critics, says today that while he would allow the Bush tax cuts to expire and thus return the top rate to 39.6 percent, “beyond that, I think, is too high.”

Further, if Reagan had sacrificed his tax plans to balancing the budget, it’s likely that Congress would have just driven up spending higher still. One of Reagan’s spending victories illustrates this risk. In 1983, Reagan and Congress reinforced Social Security, gradually raising the retirement age, speeding up payroll-tax increases, and making more people eligible so that they would be paying into the program. The tax changes filled Social Security’s coffers, as baby boomers were in their peak earning years. But Washington never banked the surpluses to strengthen the nation’s position for when these earners began to retire. Instead, it borrowed from Social Security for general spending.

There was also a psychological component to Reagan’s choice. He concluded that a big fight on every appropriation was not what the country needed to heal and grow. The president obviously listened to the advice of a young congressman, Richard Cheney. As Cheney said at a 1981 budget meeting (Stockman’s book, The Triumph of Politics, recounts the story), “This isn’t the right time to launch a blood-letting. . . . People are shell-shocked and angry. You’re not going to get a consensus for anything very big or meaningful. . . . The deficit isn’t the worst thing that could happen.”

Time will tell if the country is prepared for deep spending cuts today. To date, it isn’t even clear that the Republican Party is. Sure, Republicans won big in the 2010 midterms partly because Tea Party activists were fed up with deficits and debt, but most of the voters’ anger seemed to be directed against bank bailouts and the stimulus, temporary programs that will extinguish themselves without the party’s help. On general spending, the party’s most concrete plan was to “cut government spending to pre-stimulus, pre-bailout levels,” hardly a benchmark for fiscal soundness. Some Republicans attacked Obamacare with the argument that it would consume Medicare resources—a muddled message, if what you really want is to cut Medicare and other entitlement spending. More recently, the Republican tax compromise with Obama includes a “temporary” new tax break on Social Security payroll taxes, a step in the wrong direction on entitlements.

The president and Congress can act nonetheless. Obama should appoint a panel to explore “reinventing government,” to recall a phrase popular during the Clinton years. At a minimum, that would mean going through agencies line by line to root out excess spending and regulation. Obama could achieve “genuine cooperation on spending reduction, taking a rigorous look at hundreds of different programs,” Meese says. Bell agrees: “The incoming class” of Republicans in Congress, he points out, “is well focused on spending.”

But, of course, we already know how to cut spending: you just cut it. So far, unfortunately, we haven’t had the political will to do that.

Eventually, markets could fix our deficit for us. If, one day, the national debt has ballooned so hugely that the American government can no longer borrow nearly for free, it will have to slash spending, hike taxes, or both. It may be that we’ll need something like another financial and economic apocalypse, one worse than the past three years’, before we change our ways.

As long as we have time, we should use it to encourage economic growth. Reagan’s example suggests how. We should keep tax rates low enough to encourage innovation and investment. We should rearrange government spending, investing more in assets that help the private sector compete and less in social programs that dampen the spark to produce.

For Reagan, surrendering to gloom was not an option. “We want the good old Reagan optimism,” says Shultz. That optimism grounded itself, oddly enough, in a cheerful piece of pessimism. As Reagan noted in his diary a quarter-century ago, “No economist can predict more than 1 yr. ahead (if that) with any degree of accuracy.”