With Republicans in control of Congress and Donald Trump back in the White House, many in the GOP see immigrationas a top priority. Focusing on the issue would help them consolidate a wavering House GOP caucus, while delivering on some core Republican campaign promises. Their chance to do so will come with a big event on the congressional calendar: passage of a reconciliation bill.

One of the more arcane elements of congressional procedure, reconciliation has been a vehicle for passing some signature elements of recent presidencies, from George W. Bush’s tax cuts to Joe Biden’s stimulus bill. Republicans now hope to use it to extend their last tax cut, as well as advance other GOP priorities—including immigration. They’re right to see an opportunity there. A recent Fox News poll found immigration tied with the economy as the issue that voters thought Trump should most prioritize. And the new administration’s executive decisions are already playing a role in staunching the border crisis.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

Nevertheless, Congressional Republicans could move the needle on immigration enforcement, and their first opportunity to make that happen is through reconciliation. But they will need to climb some procedural hills first.

A product of the 1974 Congressional Budget Act that has been refined since, reconciliation originated as an option to help expedite budgeting. The reconciliation process circumvents the filibuster in the Senate, so reconciliation votes can pass with a bare majority. Though Congress has come to use it as a narrow door to squeeze through big-ticket items, reconciliation was originally envisioned in part as a way of promoting a balanced budget.

The process has many limitations. Provisions of any reconciliation bill must deal primarily with the budget (taxes, spending, and the debt ceiling). Reflecting that balanced-budget heritage, reconciliation bills cannot add to the deficit after a ten-year period. The Senate parliamentarian, Elizabeth MacDonough, gets to determine which provisions fulfill the procedural requirements.

Funding for more border control officers, more beds for detained migrants, and additional enforcement efforts seem well within the bounds of recent reconciliations. The Inflation Reduction Act, for example, supplied the IRS with over $45 billion for hiring more immigration-enforcement agents. The IRA also allocated $1.5 billion to the Energy Department’s Office of Science to fund the construction of research facilities, suggesting that money for a border wall or fencing could also conceivably pass via reconciliation.

More general statutory changes to immigration policy, however, might strain the bounds of reconciliation. Because reconciliation is primarily supposed to deal with budgetary matters, policy proposals for which the budgetary impact is nil or “merely incidental” can’t pass through this means.

This limitation has proved a problem for Democrats’ past attempts to use reconciliation to set immigration policy. During the first two years of the Biden administration, the Senate parliamentarian repeatedly shot down its proposals to legalize illegal immigrants via reconciliation. In one case, MacDonough said that such an amnesty provision would be a “tremendous and enduring policy change that dwarfs its budgetary impact.” A similar attention to long-term consequences might guide the parliamentarian’s thinking this time around.

Still, some policy creativity could yield reforms that gratify diverse factions within the Republican coalition. For example, both tech proponents and MAGA critics of H-1B visas for high-skilled workers agree that the program does not distribute visas efficiently. Currently, H-1B visas are allocated by a random lottery. As Manhattan Institute fellow Daniel Di Martino and others have argued, it could be more effective to instead award visas to applicants with the highest-paying job offers. This would be more in line with the program’s function, which is bringing in high-skilled talent not otherwise available domestically.

To incorporate such a measure into the reconciliation bill, Republicans could include a provision that ranks visas by salary and raises some revenue from structuring the H-1B process this way. The revenue-generation component would be crucial for including this reform in the reconciliation bill. Policymakers would need to be able to argue that this revenue was not “merely incidental” to the budget and that ranking visas on wages was itself a key part of generating revenue.

This revenue-generation could be structured in various ways, but one option would be to levy an “invest in America” surcharge (of, say, 10 percent to 20 percent) on the salary offered by employers. This surcharge, which the employer would pay, has an obvious policy logic: if these workers are truly needed, their employers should be willing to pay a tax to get access to their services. The proceeds of the surcharge could then be reinvested in the American educational system. The surcharge would create a tension in the process of distributing H-1B visas: employers would be incentivized to bid against each other to compete for the visas, but—as they bid salaries up—they would also be increasing the cost of these visas. That increased tax burden would discourage companies from using the H-1B if equivalent skilled workers were already present domestically, but the H-1B program would still be there as a hiring pipeline if U.S. businesses could not find U.S. workers for open positions. Arguably, this kind of H-1B reform would be a stopgap until Congress passes a broader reform of the legal-immigration system to prioritize employment (a structural change that would most likely fall outside the reconciliation process).

The recent bipartisan vote to pass the Laken Riley Act—requiring the detention of illegal immigrants charged with theft or burglary—illustrates how Republicans would be wise not to confine their immigration efforts strictly to reconciliation. Bipartisan efforts to improve the asylum system, strengthen enforcement, and bolster skill levels in the legal immigration system are achievable. Some of these reforms would probably require going through the normal legislative process. But by indicating that Republicans are willing to take some action on their own, reconciliation could be an important piece of immigration’s policy puzzle.

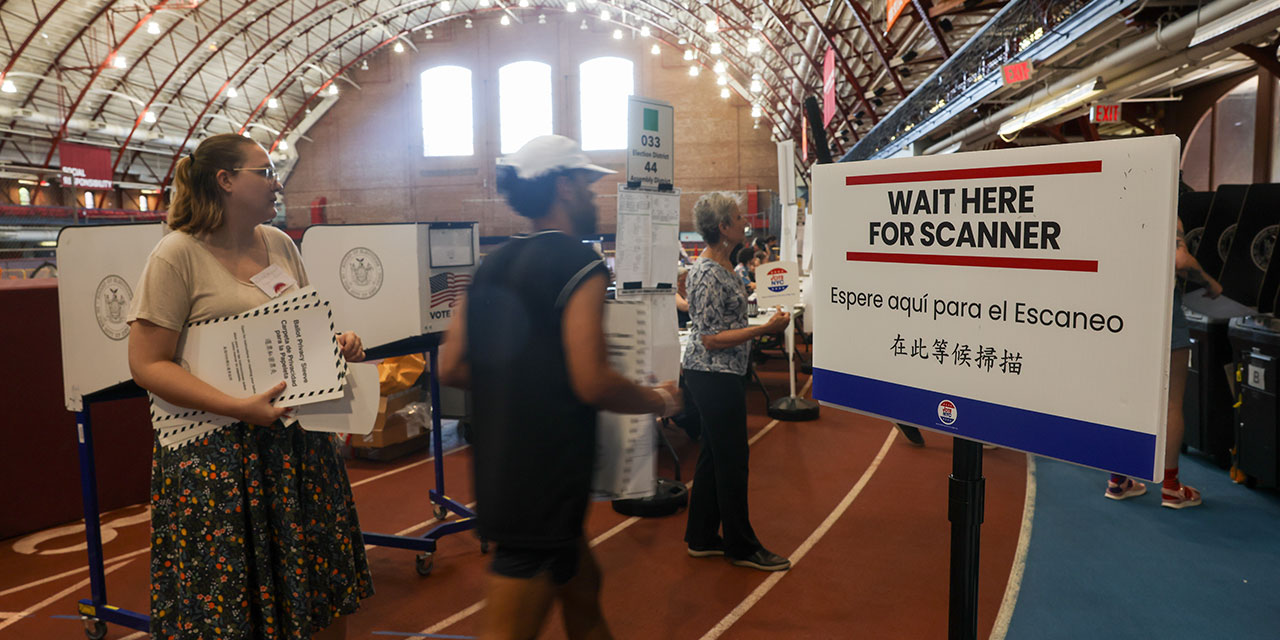

Photo by Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images