Every 50 years or so, California makes a claim for jazz preeminence—and then loses its way. Will it work out better this time?

Don’t believe anyone who tells you that jazz originated on the West Coast. It’s just the word for jazz that started out in California. But it could have been so much more.

The term first appeared in the Los Angeles Times in 1912, when a baseball pitcher bragged about his “jazz ball”—so wobbly that no one could hit it. Soon the word showed up in San Francisco newspapers, also in a sports context. Before long, “jazz” was linked to anything different, exciting, or dynamic. Around 1915, people finally connected the word with a hot new style of music that would soon take the nation by storm. New Orleans gets credit for originating the music itself, nurturing this bold performance style at least a decade before it got christened as jazz. But California might have taken over the music, too, and set itself up as a home base for the first generation of jazz performers. The musicians were willing, and, for a while, it looked as though it would happen. That was the first wave of West Coast jazz.

By my measure, there have been two subsequent waves—extraordinary moments when California stepped to the forefront of the genre and seemed ready to assert itself as the creative center and trendsetter in the music. The first two waves crested and ended in failure. The third wave is happening now.

The first golden age of West Coast jazz offers an intriguing case study in missed opportunities. At an early juncture, New Orleans jazz musicians looked for opportunities elsewhere, and California proved alluring. In 1894, the Southern Pacific introduced the Sunset Limited, offering regular train service from New Orleans to Los Angeles—only the second transcontinental route in the United States. More than 20 years before the Panama Canal opened up a practical sea route, passengers could travel by rail to California in just 60 hours.

An extraordinary roster of jazz talent would take advantage of this fast track to Los Angeles. New Orleans–born pianist Jelly Roll Morton made some of the most important jazz records during his stay in Chicago in the mid-1920s; but Morton spent five years on the West Coast before those midwestern glory days, including stints in Los Angeles, San Francisco, Oakland, Tacoma, and Vancouver. King Oliver is now celebrated as the hero of Chicago jazz, and his hiring of Louis Armstrong in 1922 marks a milestone in the art form’s history. But Oliver was gigging on the West Coast before setting up shop in Chicago—and, under different circumstances, might have brought Armstrong to California instead. New Orleans trumpeter Freddie Keppard came to L.A. in 1914 and performed there with the greatest jazz ensemble of its day, the Original Creole Band. New Orleans trombonist Kid Ory moved to L.A. in 1919 and made the first record of black New Orleans jazz at a studio in Santa Monica—just a few yards from the Pacific Ocean.

Los Angeles was now a center of hot jazz. But every one of these musicians eventually departed the city. During the 1920s, Chicago surpassed L.A. as a magnet for jazz talent. Musicians didn’t go to Chicago for the weather or to root for the Cubs, but for career advancement, plain and simple. In California, Jelly Roll Morton could secure gigs easily enough; but in Chicago, he got a record deal and found a music publisher. In Chicago, King Oliver became a star, and his protégé Louis Armstrong became a superstar. New York would supplant Chicago as the jazz capital of the world; but for the next decade, the Windy City scene was second to none.

Jazz in California languished for decades. The state’s population doubled between 1920 and 1940, but the jazz culture felt stagnant. Occasionally, a major star traveled to the Pacific Coast for a movie appearance or an extended engagement, but this was more vacation than relocation. Even when something special happened, it never lasted. The swing band movement actually originated on the West Coast, with Benny Goodman’s 1935 appearance at the Palomar Ballroom in Los Angeles—but Goodman soon returned to the East Coast, just as every other jazz celebrity had done before him. The Pacific Coast was a lovely place to visit but was not a suitable home base for the music.

It’s still not entirely clear why that changed during the 1950s. Envious New Yorkers will tell you that it was just good marketing. Record labels promoted “West Coast jazz” as a trendy new movement during the Eisenhower era, and audiences bought into the concept. But other factors clearly played a role, too. California’s population had doubled again since 1940, and the West Coast economy was booming. Air travel made it easier for musicians to live out West without giving up opportunities back East. The growing popularity of cooler jazz sounds, less intense than the prominent New York variants, must also have helped. Given the Pacific Coast’s reputation as relaxed and laid back, it made sense that music there would epitomize the new zeitgeist of the ultrahip.

But perhaps it all boiled down to talent. The postwar generation of homegrown jazz players out West was extraordinary. Modern jazz musicians born or raised in California include Dave Brubeck, Charles Mingus, Eric Dolphy, Chet Baker, Art Pepper, Dexter Gordon, Paul Desmond, and Gil Evans, among other stars.

Everything seemed to point westward in the 1950s. Native New Yorker Gerry Mulligan had collaborated with Miles Davis on the significant Birth of the Cool recordings. In 1951, he hitchhiked to Los Angeles, launching a partnership there with trumpeter Chet Baker that turned both of them into jazz luminaries. Max Roach, the preeminent modern jazz drummer, moved to L.A. in 1953, where he formed a trendsetting quintet with trumpeter Clifford Brown. At about this same time, the big bands that had been so popular in the 1940s were struggling for survival, and many top-tier players left to set up shop in Southern California. Here they could supplement their jazz income with work on Hollywood soundtracks, advertising jingles, and commercial studio sessions. These newcomers included Shorty Rogers, Bud Shank, Harry “Sweets” Edison, Shelly Manne, Jimmy Giuffre, Bob Cooper, Pete and Conte Candoli, Frank Rosolino, and others. In the talent battle, L.A. may not have reached parity with New York, but the gap had narrowed considerably.

These same years also marked a high point in the history of San Francisco jazz. Local hero Dave Brubeck had grown into a national celebrity, even appearing on the cover of Time in 1954. His Fantasy label, founded in San Francisco in 1949 and later relocated to Berkeley, launched the careers of other star-bound Bay Area artists, including pianist Vince Guaraldi (best known for his Charlie Brown Christmas soundtrack), Latin jazz pioneer Cal Tjader, and, in the late 1960s, the rock band Creedence Clearwater Revival. Creedence’s string of gold records gave Fantasy the financial resources to acquire several other labels, and it established itself as the largest indie jazz record company in the world.

But these few success stories could not hide the sharp decline in West Coast jazz during the 1960s. By the middle of the decade, the glory years in West Coast jazz were over—again.

What happened? Why did jazz lose momentum in California but stay vibrant in New York?

Some of it was happenstance and personal. Drug problems put an all-star contingent of West Coast players into prison, including Art Pepper, Hampton Hawes, Frank Morgan, and Dupree Bolton, and forced Chet Baker overseas, where his heroin use was more tolerated. Dave Brubeck felt that Fantasy Records had misled him about equity ownership in the label; he signed with New York–based Columbia and relocated to Connecticut.

But other problems had nothing to do with music. Jazz could hardly match the other entertainment and lifestyle attractions springing up in the West during the 1950s and 1960s, ranging from Las Vegas casinos to multimillion-dollar theme parks. Southern California jazz promoter Ruth Price commented that it boils down to the fact that “people come to California to go to Disneyland, not visit a jazz club.” Price, who made her name as a jazz singer, later found a loyal audience in running the Jazz Bakery, one of the most important California clubs of the last 20 years. But she won’t pretend that live music is central to the local culture. “The problem here is purely geography—it’s all so spread out. It’s not like in New York or other major cities where everything is concentrated in a downtown area. That’s always been the problem.”

Yet the biggest reason that jazz stagnated in California after 1960 was the same one that had stopped the jazz resurgence back in 1920: the leading players found better opportunities elsewhere. Some turned to lucrative studio work—for example, pianist Victor Feldman, who turned down an offer to join Miles Davis’s band because the money doing commercial sessions was so much better. (Herbie Hancock got the job with Miles instead.) Other L.A. players, such as Charles Mingus and Dexter Gordon, maintained their allegiance to jazz but felt that they could have more impact in a different locale. The exodus got going at the close of the 1950s, when Eric Dolphy and Ornette Coleman moved back East. Their decisions were validated by the career boosts that they enjoyed after they left California behind.

The cumulative impact of these shifts was devastating. At every turn, West Coast jazz was losing its stars; in Hollywood and its environs, that’s the one unforgiveable sin.

I came of age as a musician on the West Coast in the aftermath of this decline. My formative experiences in Los Angeles and San Francisco in the 1970s and 1980s brought me into contact with outstanding musicians who enjoyed the California lifestyle; but they all knew that reputations got made in New York. I was a passionate advocate for the local scene, and even wrote about it in West Coast Jazz (Oxford University Press), celebrating the legacy and achievements of the great California artists. But all this was ancient history by the time the book appeared in 1992. No one out West seriously felt that the local scene could challenge New York’s dominant position.

It’s taken a long time, but that may finally be changing. For the first time in a half-century, West Coast musicians are more than just poor relations of their elite East Coast colleagues. It feels like a movement, a trend, the next new thing.

Los Angeles saxophonist Kamasi Washington is the hottest horn player in jazz right now, and he’s part of a cadre of Southern California musicians promoting a dialogue with popular styles and commercial genres. This cohort of young West Coast jazz innovators includes bassist Thundercat, producer Flying Lotus, and composer/performer Terrace Martin. Every one of these artists was born in Los Angeles. Who needs to steal talent if you can nurture your own superstars?

These players do not lack ambition. Washington’s breakout 2015 album The Epic features three hours of intense, action-packed music played by a ten-piece jazz band, accompanied by 20 singers and a 32-member orchestra. Is any other jazz musician on the planet thinking on such an Olympian scale? When Washington completed the recording sessions, the music filled two terabytes of storage; if he had released all 190 songs, they would have filled eight albums.

Even in its downsize form, The Epic is suitably named, and its impact has been monumental. It didn’t hurt that hip-hop star Kendrick Lamar invited Washington to perform and handle arrangements on To Pimp a Butterfly, also released in 2015, and destined to go platinum. Lamar won the Pulitzer Prize in music in 2018. In a matter of months, Washington had gone from little-known Los Angeleno to mastermind behind two of the biggest recordings of this era.

This same refusal to accept boundaries and obstacles is evident elsewhere among the new generation of California players. Flying Lotus, the professional name of Steven Ellison, is part of an esteemed jazz family that traces back to his great-aunt Alice Coltrane, widow of the iconic saxophonist John Coltrane. His influences span from Miles Davis to J Dilla. He is also the entrepreneur behind the influential Brainfeeder record label that released The Epic, as well as a budding movie director. His controversial 2017 “body horror” film Kuso caused a scandal at the Sundance Film Festival. Many in the audience walked out, overwhelmed by the brutal imagery. The “no limits” mentality of the L.A. artists always comes to the forefront.

Yet it would be wrong to view the resurgence of West Coast jazz as merely a matter of individual personalities. The institutional changes afoot may prove far more important over the long run. Many of these have taken place behind the scenes, unnoticed by fans. But not every milestone in music happens on a bandstand or in a recording studio. For the California jazz ecosystem, the most important change has been the rise of a new array of well-run nonprofits capable of attracting donors, securing grants, and building audiences in urban communities. They have transformed the scene, giving West Coast jazz more stability than ever before.

The most visible sign of this change is an extraordinary building: the SFJAZZ Center, the largest stand-alone jazz performance facility in the United States. The eventual price tag on the completed structure, which opened in 2013, was $66 million. It hosts about 400 jazz events a year, with 150,000 people coming through its doors. In an earlier age, jazz fans in San Francisco took pride in their small, quirky nightclubs such as the Black Hawk, which operated on Hyde Street from 1949 to 1963, or the Keystone Korner, which flourished in North Beach from 1972 to 1983. Fans loved the intimate atmosphere, but these small operations couldn’t weather downturns in the jazz economy. SFJAZZ is built on a much larger scale and, like the symphony hall and the opera house, is designed to last.

“The nightclub model is not one that you can transfer into the nonprofit approach,” explains founder and artistic director Randall Kline. “We needed to turn to other role models—symphony, opera, ballet.” He built this remarkable organization and facility despite skepticism from those who believe that jazz is in a terminal state of decline. “I have been asked how I can hope to succeed when others haven’t,” he recounts. “But I never thought there was a fixed limit to the jazz audience. I hate the phrase ‘Keep Jazz Alive,’ ” Kline says. “You hear that during pledge drives and fund-raising campaigns. Jazz couldn’t be more alive than it is right now. The goal is to push forward, not look back.”

Across the bay in Berkeley, pianist and jazz educator Susan Muscarella has pulled off a similar miracle in defiance of the “jazz is dead” mantra. Armed with little more than a passion for the music and a willingness to take out a second mortgage on her home, she has built the most successful jazz-education startup in the United States: the California Jazz Conservatory. After an apprenticeship teaching at the University of California at Berkeley, Muscarella decided to open a community music school in 1997. “I followed the view that if you build it, they will come.” They did: after five years, the Jazzschool—as it was then known—had outgrown its facility and moved into a bigger building in the Berkeley Arts District. And it has kept growing. In 2009, Muscarella launched a formal degree program, and in 2013 gained accreditation. Earlier this year, the conservatory opened a second $3.5 million building across the street.

“My aspiration is to be the Juilliard of jazz on the West Coast,” Muscarella says. This may seem a wild dream, but those aware of what she has achieved so far won’t rule out that possibility. When I spoke with her, Muscarella’s conversation was filled with plans—a new master’s program for composers and performers, accreditation for tenure from the National Association of Schools of Music, and expanded academic and fund-raising efforts, among other items on her expansive list.

Muscarella laughs when I ask her whether jazz is in decline. She points to her work with the Monterey Jazz Festival’s “Next Generation” program for student musicians. “About 1,300 students participate, and if you look at the enthusiasm of these musicians, as well as the parents and audience, you would never even consider the possibility that jazz is challenged.”

Tim Jackson, artistic director of the Monterey Jazz Festival, tells a similar story. He notes that “last year was a big year for us, our 60th anniversary, and we saw a spike in ticket sales and interest in the festival.” The three-day event draws almost 40,000 attendees, many coming from out of state.

Unlike other festival impresarios, Jackson hasn’t tried to replace jazz artists with rock and pop acts. “We do stretch boundaries, but all our artists have some connection with jazz. The history of the festival is deeply rooted in jazz, and I’m not going to be the person who changes it.”

Other jazz institutions out West are also on a growth trajectory. The Thelonious Monk Institute of Jazz Performance is flourishing at UCLA. The Stanford Jazz Workshop, launched in 1972, is bigger and better than ever. The University of the Pacific’s Dave Brubeck Institute will soon celebrate its 20th anniversary. Unlike the jazz venues of the past, which came and went, these enjoy backing from well-heeled donors and premier institutions.

This is the new face of jazz out West. Exciting younger artists with grand ambitions are revitalizing the idiom; a robust support structure, from festivals to conservatories, is providing stability and a future-oriented confidence that has never existed. Taken together, these things represent the third great wave of West Coast jazz. This time, it just might last.

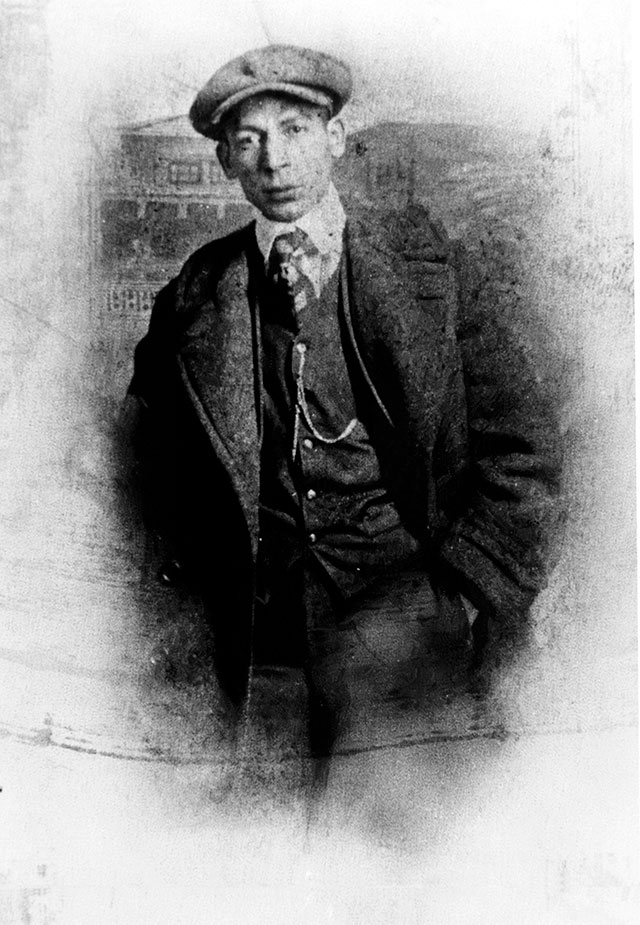

Top Photo: The postwar generation of homegrown jazz players in California was extraordinary, and included trumpeter Chet Baker. (JP JAZZ ARCHIVE /REDFERNS/GETTY IMAGES)