To the average American not employed as an industrial engineer or a member of a problem-solving team at some big business, the term “root causes” would have seemed obscure until a few weeks ago. But then Vice President Kamala Harris became the Democratic Party’s presidential nominee, and her record assumed new importance. One seemingly important task that President Biden handed Harris at the outset of their administration was to address the underlying reasons for mass illegal immigration to the U.S., a problem that voters rank among the top issues in the November election. Critics argue that Harris bears some of the responsibility for the Biden administration’s failure to stem the flood of illegals into the country; supporters contend that she was never in charge of border security. Her job instead, they say, was to tackle immigration’s “root causes.” What, exactly, does that mean? How does it apply to public policy questions like immigration? And how should we judge what Harris came up with?

The notion of root-cause analysis in public policy has been controversial for decades. It involves taking a way of thinking about business problems that affect tangible systems—like, say, a production line—and applying it to more complex structures like human societies. Root-cause analysis originated in industry in the 1950s and is often closely associated with the Toyota car company of that era, which developed systematic ways of addressing industrial problems not merely to fix some glitch in a system but also to understand the deeper sources of the problem and prevent it from reoccurring. A classic example would be a manufacturing firm whose production equipment starts breaking down with unusual frequency. The obvious place to look first, in this case, would be whether the company’s maintenance program has somehow failed. But if that’s not the issue, then the firm might require a deeper dive into its entire operation that ultimately uncovers unexpected causes, like a change in the quality of replacement parts that a vendor is providing.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

Over time, root-cause analysis evolved into a series of techniques that spread to many industries beyond manufacturing, including health care, where a hospital might use it to uncover the causes of a troubling rise in post-surgical infections. Perhaps the most famous case of this kind of systematic thinking was the process NASA engineers employed to identify what had hobbled the Apollo 13 spacecraft and to find solutions to bring the astronauts back alive. The space agency has applied the technique to understand some of its biggest failures, including the loss of the Mars Climate Orbiter in September 1999, thanks to what turned out to be a mathematical error.

Soon social thinkers were applying root-cause analysis to social problems. During the Johnson Administration’s War on Poverty in the 1960s, the White House created a commission to address rising crime, especially in America’s cities. Though the commission offered a few practical solutions, it defaulted to a root-causes explanation, namely that crime could “only be reduced by fundamental social changes,” such as reduced poverty and deprivation—a conclusion that deemphasized the role of deterrence. Over time, despite evidence from thinkers like eminent political scientist James Q. Wilson, who showed how reforming policing techniques and employing more cops in troubled areas reduced crime, the idea spread that the only way to address crime was through neighborhood antipoverty programs.

Such thinking led to an almost fatalistic approach holding that in the short-term society was helpless before rising disorder, because only long-term social transformations were meaningful. New York City mayor David Dinkins epitomized that idea when, responding to a weekend of mayhem in the city in the early 1990s, he said, “If we had a police officer on every other corner, we couldn’t stop some of the random violence that goes on.” New York’s next mayor, Rudy Giuliani, demonstrated the fallacy of that statement by driving down crime with much less than a cop on every corner, in the process unlocking the potential of depressed communities. Rather than prosperity being the foundation of lower crime, Giuliani showed that reducing crime first sparked community prosperity. Even so, the root-causes argument has continued to play a role in politics, most recently in Chicago, where current mayor Brandon Johnson has blamed disinvestment in local neighborhoods for rising crime, and where for eight years Cook County State’s Attorney Kim Foxx cut incarceration rates and stopped prosecuting nonviolent crimes like shoplifting because such crackdowns were considered racist.

Unlike in business, where troubleshooters have a massive financial interest in fixing problems in the most direct and effective way, social thinkers have distorted root-cause analysis to ignore empirically effective solutions in favor of deeper human interventions, often speculative at best. The problems of mass immigration are particularly challenging in this regard, given that the interventions an American policymaker might propose would have to prove effective in foreign countries, where we have much less direct power than in our own communities.

The basic problem of mass immigration to the U.S. is that we are enormously more prosperous and stable as a society than every other country in the Western Hemisphere to our south. The root-cause solution to that problem is nothing less than wholesale transformations of countries so that their migrants might be willing to stay home instead of venturing here. How realistic is that idea? Venezuela is a case in point. With its petrol economy, the nation was not a significant source of outmigration for decades. In fact, Europeans fleeing their own countries often chose to settle there. But then Hugo Chavez seized power in 1999 and began nationalizing the country’s oil industries. Venezuela’s economic fortunes and social stability crumbled. The number of Venezuelans who’ve fled to live elsewhere subsequently soared from less than half a million in the early twenty-first century to about 7.7 million today. They’ve flooded other South American and Caribbean countries as well as the U.S. In just three years, the number of Venezuelans attempting to cross over the southern border into the U.S. has exploded from about 50,000 to more than 300,000 annually. Short of an unlikely military intervention that changes the country’s leadership, there’s only so much America can do to reduce this outmigration.

Considering the obstacles, Harris wasn’t in an enviable position when Biden gave her the task of coming up with root-cause solutions to immigration back in February 2021. Under her, the National Security Council did produce an 18-page report recommending five massive tasks to stabilize countries like Honduras and Guatemala. They involve promoting growth by wholesale reform of countries’ economies and legal systems, helping to create new industries to export goods to the U.S., combating corruption and promoting transparency in government, promoting labor reform and a free press, and tackling criminal gangs and sexual violence. Every one of these goals is self-evidently worthy, but also almost entirely beyond Washington’s control. The U.S. can’t merely conjure up democracy, transparency, a free press and the rule of law in failed states that haven’t had them for generations.

Over time, root-cause thinking in social policy has become a political palliative. It’s a way for those with ideological objections to effective solutions—like better policing or stronger border security—to offer an alternative to voters by claiming that they’ll do something about the problem that is deeper and more meaningful than the obvious solutions. It’s often enough, as we’ve seen in Chicago with Johnson’s election, to pacify voters—at least until the problem becomes so destabilizing that voters turn on you.

Voters now say by a significant margin that they favor Donald Trump to deal with the immigration problem. Trump offers direct, not root-cause, solutions: more border security, an end to paroling of asylum seekers into the country, and an increase in deportations. The Biden administration has recently acknowledged that voters prefer this approach by moving to tighten border security in advance of the election. It’s no surprise that the closer we get to November, the less likely candidates are to tout root-cause remedies.

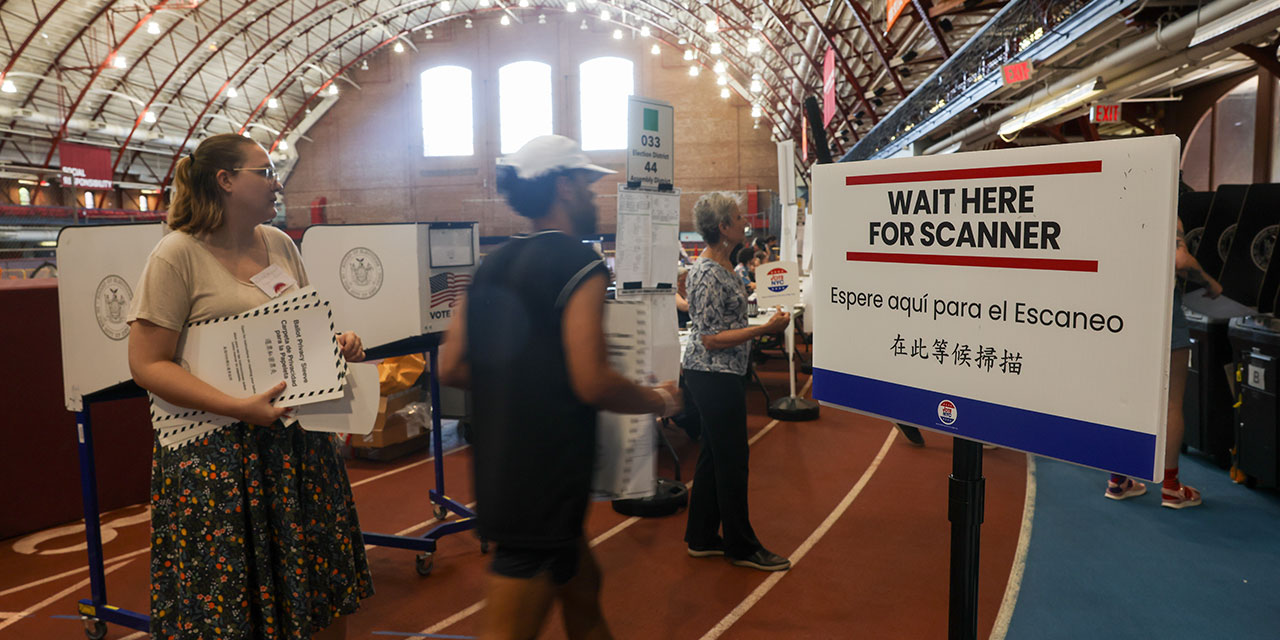

Photo by John Moore/Getty Images