In the summer of 1966, Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach warned that there would be riots by angry, poor minority residents in “30 or 40” American cities if Congress didn’t pass President Lyndon Johnson’s Model Cities antipoverty legislation. In the late 1960s, New York mayor John Lindsay used the fear of such rioting to expand welfare rolls dramatically at a time when the black male unemployment rate was about 4 percent. And in the 1980s, Washington, D.C., mayor Marion Barry articulated an explicitly racial version of collective bargaining—a threat that, without ample federal funds, urban activists would unleash wave after wave of racial violence. “I know for a fact,” Barry explained, “that white people get scared of the [Black] Panthers, and they might give money to somebody a little more moderate.”

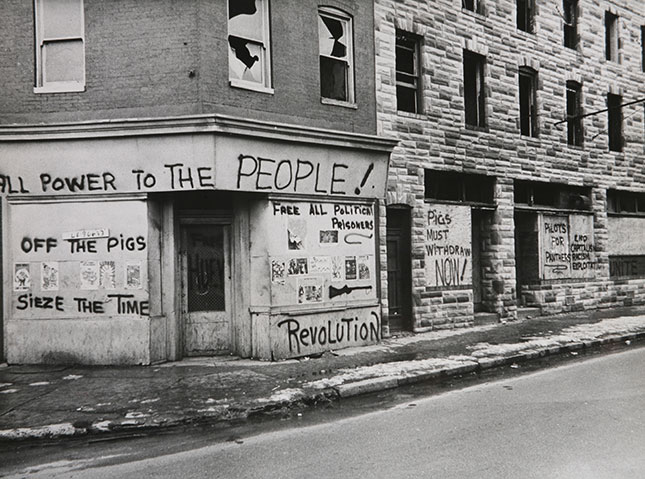

This brand of thinking, which I have called the riot ideology, influenced urban politics for a generation, from the 1960s through the 1980s. Perhaps its model city was Baltimore, which, in 1968, was consumed by race riots so intense that the Baltimore police, 500 Maryland state troopers, and 6,000 National Guardsmen were unable to quell them. The “insurrection” was halted only when nearly 5,000 federal troops requested by Maryland governor Spiro Agnew arrived.

In the years since 1968, Baltimore has proved remarkably adept at procuring state and federal funds and constructed revitalization projects such as the justly famed Camden Yards and a convention center. But Baltimore never really recovered from the riots, and the lawlessness never fully subsided. What began as a grand bargain to avert further racial violence after 1968 descended over the decades into a series of squalid shakedowns. Antipoverty programs that had once promised to repair social and family breakdown became by the 1990s self-justifying and self-perpetuating.

In the wake of the 2014 riots in Ferguson, Missouri, and the 2015 West Baltimore riots, a new riot ideology has taken hold, one similarly intoxicated with violence and willing to excuse it but with a different goal. The first version of the riot ideology assumed that not only cities but also whites could be reformed; the new version assumes that America is inherently racist beyond redemption and that the black inner city needs to segregate itself from the larger society (with the exception of federal welfare funds, which should continue to flow in). This new racial politics is not only coalescing around activists claiming to speak for urban blacks—represented publically by groups like Black Lives Matter—but is also expressed in the writings of best-selling author Ta-Nehisi Coates. And Baltimore is once again center stage.

The West Baltimore rioters of 2015 didn’t call for more LBJ-style antipoverty projects but for less policing. In a “keep off our turf” version of belligerent multiculturalism, the rioters see police as both to blame for black criminality and as an embodiment of bourgeois white values. The old riot ideology referred to mostly white urban police forces as occupying armies; the new version sees even Baltimore’s integrated police force, under the leadership of the city’s black mayor and (until recently) a black police chief, as an occupying army. Withdrawing the police from black neighborhoods is the only acceptable solution.

In his memoir The Beautiful Struggle, Coates described how his father, a former Black Panther and full-time conspiracy theorist, drove his son around West Baltimore “telling me again the story of the black folk’s slide to ruin. He would drive down North Avenue and survey the carry-outs, the wig shops, the liquor stores and note that not one was owned by anyone black.” Whites had “plundered” what belonged to blacks, his father explained, as they had done with once-great African kingdoms. Coates, who lived in fear of black street toughs as a teen, sees the police as a greater threat to black well-being than the drug “crews” and gangs roaming the streets of West Baltimore today. His vision, in part, is to free gang-ridden areas from the malign grip of white standards and aggressive policing. Coates has adopted his father’s view that “our condition, the worst of this country’s condition—poor, diseased, illiterate, crippled dumb—was not just a tumor to be burrowed out but proof that the whole body was a tumor, that America was not a victim of a great rot but the rot itself.” Not even a hurricane of violence, says the new riot ideology, justifies a vigorous police presence in black localities.

Baltimore, historian Joseph Arnold wrote, was a city with a Southern culture and a Northern economy “that retained nineteenth-century airs well into the twentieth.” Like the rural and slaveholding Eastern Shore of Maryland, Baltimore had been strongly Confederate in its sympathies, casting only 3 percent of its vote for Abraham Lincoln in 1860. The first deaths in the Civil War occurred in the Pratt Street Riot of 1861, when pro-Southern Baltimoreans attacked Northern troops moving toward Washington. Fort Sumter had been fired on a week earlier. For a century after the Civil War, the alliance of Baltimore, which imposed a harsh segregation regime in 1911, and the Eastern Shore, where antiblack sentiment had never relented, dominated Maryland politics. Well into the 1960s, Baltimore was a thoroughly segregated city.

The city’s dominant political figure post-1968 was the colorful William Donald Schaefer. A meld of old-style machine pol and new-style harvester of federal funds, Schaefer served as mayor from 1970 to 1987 and then as a two-term Maryland governor. Under Schaefer’s mayoral leadership—and with the help of Senators Paul Sarbanes and Barbara Mikulski—Baltimore became, in effect, a second Federal City, cadging a disproportionate share of federal subventions that produced numerous but invariably ineffectual antipoverty efforts. “Bureaucrats lived well off the anti-poverty programs,” explains Baltimore writer Van Smith, “without enhancing the lives of the poor.”

Schaefer knew his city intimately. He never tried to reform the culture of police corruption. His machine counted on characters like Irv Kovens, who sold furniture, sometimes on credit, to poor families. Kovens employed 35 collectors who visited those behind on their payments. Come election time, the collectors proved valuable as sources of political information and as canvassers for Schaefer. African-Americans got their cut of patronage via the school system, which was largely turned over to their oversight. While eventually coming around on segregation, Schaefer tolerated the views of some politicians from the city’s white districts who opposed civil rights because, he explained, “they never had any black people down there. They had an old-time prejudice.”

In 1987, the city elected its first African-American mayor, Kurt Schmoke, a Baltimore-bred, Ivy League–educated former federal prosecutor who campaigned on continuing Schaefer’s crony-capitalist policies of “bringing business into government” via federal funding. Schmoke won 65 percent of the white vote against his Republican opponent. While the transition to an African-American mayor occurred without serious acrimony, city councilwoman and future mayor Sheila Dixon foreshadowed racial problems to come in 1991, when she lost her cool during a redistricting debate and waved a shoe at her white colleagues. “You’ve been running things for the last 20 years,” Dixon barked. “Now the shoe is on the other foot. See how you like it on the other foot.”

The pace and scale of subsidized governmental experimentation accelerated during the first eight of Schmoke’s 12 years in office. Trying to achieve an antipoverty breakthrough in the West Side neighborhood of Sandtown-Winchester, Schmoke worked with the city’s leading developer, James Rouse, former president Jimmy Carter, and a group of private philanthropies. (Sandtown is where Freddie Gray, whose death in police custody set off the 2015 Baltimore riots, was born in 1990.) Rouse pushed for Sandtown’s transformation with new housing, employment programs, and prenatal care. “This is going to be the most important thing I do in my life,” said Rouse, a man of numerous achievements. But the city’s political and social pathologies swamped the developer’s efforts.

During the Schmoke era (1987–99), Baltimore repelled small businesses unable to cut deals with city hall. Baltimore imposed property taxes double those of surrounding areas, in part because it maintained a government workforce 50 percent larger than those of comparable-size cities. Baltimore’s murder rate was five times that of Boston. “Charm City” also suffered the highest rate of syphilis in the country—18 times the national average. Schmoke, who tried to hire Nation of Islam foot soldiers to patrol the city’s housing projects, decided that drugs were a public health problem, not a matter of criminal justice. Funded in part by billionaire investor George Soros—who would later bankroll key groups in the Black Lives Matter movement—a Schmoke administration initiative distributed clean needles to heroin addicts. Baltimore became the most addiction-ridden metro area in the country. President Bill Clinton’s drug-policy office described Baltimore as a city where “heroin is readily available with city dealers moving into suburbs and high schools; cocaine is plentiful in both crack and powder forms.” The city’s 60,000 drug addicts—nearly one in ten Baltimoreans—overwhelmed hospitals with cocaine-induced emergencies.

Schmoke’s exhortations far exceeded his achievements. During his three terms, Baltimore—endowed with multiple federal programs to incentivize business development—lost 56,000 jobs and became a city of transfer payments fueled by nonprofits and government. Schmoke produced perhaps the greatest gap between image and reality in any American city. For example, he had city cars and trucks painted with his campaign slogan—“The City That Reads”—but his cuts in library funding reduced opportunities to read. While the hyperactive Schaefer had proved spasmodically effective, Schmoke’s stylistic trademark was—speeches and slogans aside—passivity in the face of the city’s problems. “It’s out of our control” was his favorite refrain, and this attitude reverberated through city government. Calls to city agencies were commonly answered—after many attempts—with a snarling, “Yeah?”

Without major accomplishments to run on, Schmoke sought a third term in 1995 on a Black Power platform. Schaefer was by then Maryland’s governor, and Schmoke mocked the $100 million convention center being built in downtown Baltimore as “cosmetic.” Schmoke was right, but his own record offered no constructive alternative—middle-class blacks and whites continued to flee for the safety and lower taxes of the suburbs. Schmoke touted his close ties with the Clinton administration, whose Department of Housing and Urban Development provided growing support for the city’s failed social programs, including a $100 million empowerment-zone grant intended to spur job creation. The jobs didn’t come, but both the empowerment zone and the Rouse-led Sandtown-Winchester Development Corporation have been favorite stops for touring HUD officials. Twenty years later, Sandtown still lacks the ordinary amenities and local shopping associated with minimally functioning neighborhoods.

In the wake of the 1968 riots, Baltimore was Maryland’s most heavily populated jurisdiction. But having shrunk from 906,000 residents in the early 1970s to 656,000 today, the city has fallen behind Baltimore County (which no longer includes the City of Baltimore) and the suburban counties of Washington, D.C. Administratively, the city has increasingly dissolved into the state. One in every four city budget dollars comes from Maryland, and Annapolis officials play a central role in administering several city agencies. The state now controls formerly city-run institutions such as Baltimore-Washington International airport, the community colleges, the jails, and most of the public school system. The city’s two sports stadiums, Oriole Park at Camden Yards and PSINet Stadium, are run by the Maryland Stadium Authority.

The 1990s urban revival associated with mayors Rudolph Giuliani in New York, Stephen Goldsmith in Indianapolis, John Norquist in Milwaukee, and Richard M. Daley in Chicago bypassed Baltimore. While crime began dropping in other cities in that decade, and particularly in New York, B’lmer, as natives sometimes pronounce it, suffered through nine straight years of more than 300 murders. Schmoke left the city with a demoralized police force, riven by racial suspicions that produced a flight of veteran cops to surrounding jurisdictions. The city lost more than 120,000 residents during the 1990s; tens of thousands of homes were simply abandoned, and parts of the city seemed degraded beyond hope of repair.

These desperate circumstances led a number of black leaders (including the father of future mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake) to back a white city councilman, virtually unknown outside his home territory in Northeast Baltimore, to succeed Schmoke as mayor. When 36-year-old Martin O’Malley, a former state prosecutor, announced his candidacy in June 1999, he didn’t even make the front page of the Baltimore Sun. O’Malley had built his council reputation by calling for tougher crime-fighting strategies. He promised that making the streets safer would “attract jobs, improve schools and halt the exodus of 1,000 city residents a month,” the Sun observed. He faced long odds—eight black candidates were already running in the Democratic primary. “The only thing he has going for him is he’s white,” said one key campaign consultant dismissively.

Felony convictions disqualified some of O’Malley’s African-American mayoral opponents, but city council president Lawrence Bell had strong public-sector union support, and former city council member Carl Stokes eloquently opposed the tax breaks handed out to downtown hotels. Yet even Bell had been recently sued for failing to pay his personal debts, and his car had been repossessed, while Stokes gave an unconvincing explanation for why his driver’s license had been suspended and then lied about whether he had graduated from college. While his rivals foundered, O’Malley began city council meetings with a roll call of recent murder victims. At the candidate’s first public forum, “O’Malley silenced the hall with a passionate pledge to end the exodus of city residents by wiping out open-air drug markets,” the Sun reported. Striking at Schmoke’s legacy, O’Malley declared that Baltimore would never lure new companies to enterprise zones until it secured drug-free zones. “People are tired of the crime—tired,” said one middle-aged black woman who plunked for O’Malley.

Elected with a cross-racial coalition, O’Malley initially brought energy and optimism to the executive office. While Schmoke had insisted that New York’s policing success was “nonsense” and “a license to hunt minorities,” O’Malley brought in Ed Norris from Giuliani’s NYPD as police commissioner and directed the police to crack down on quality-of-life offenses. Norris introduced a version of Gotham’s highly successful CompStat system for tracking crime. Further, O’Malley tried to apply CompStat techniques to a range of city services. For a time, his innovative CitiStat, which applied rapid data-gathering and analysis to all city agencies, brought a degree of transparency and accountability to B’lmer’s sleepy, self-serving bureaucracy.

National magazines lauded O’Malley as an up-and-coming star in the Democratic Party, and the telegenic mayor won a featured speaking slot at the 2004 Democratic National Convention. But despite O’Malley’s efforts, the city remained in dire shape. Its industrial-age infrastructure continued to crumble. More than 100,000 of Baltimore’s schoolchildren were functionally illiterate, in part because the schools were, in effect, “owned” by the teachers’ union, led by African-Americans who, in the words of Schaefer biographer C. Fraser Smith, viewed them “as their inviolate pool of patronage.” O’Malley struggled mightily but, at best, made only a dent in the city’s rampant crime. Commissioner Norris tried to professionalize the city’s police culture, but O’Malley resented the plaudits that came his way, and Norris was shown the door after two years. Even O’Malley’s limited anticrime measures produced a backlash. He cut back on quality-of-life arrests in his second term, when he began eyeing a run for governor.

O’Malley’s reforms ended with his administration. He was succeeded by Sheila Dixon, the city council president and onetime shoe-waver. She campaigned against quality-of-life policing, by then undercut by an ACLU lawsuit. Dixon seemed more interested in revenge than results. Elected with a record-low 28 percent turnout in the Democratic primary, she had to resign three years into her term, after being convicted of petty embezzlement and perjury. Stephanie Rawlings-Blake, who succeeded Dixon first as city council president and then as mayor, continued the campaign against active policing. By the time the city erupted in the Freddie Gray riots, Baltimore had already returned to the pathological slough from which O’Malley had only partially rescued it. The tragedy of West Baltimore was that its churchgoing pockets of rectitude found themselves caught between criminal crews, on the one hand, and corrupt cops, on the other.

Sandtown itself, though emblematic of Great Society–inspired efforts at urban reform, made a somewhat atypical urban slum. To the west and south is Gwynn’s Falls Park; to the north are Hanlon and Druid Hills Parks and, slightly to the east, Green Mount Cemetery. West Baltimore also includes Baltimore Community College and the historically black Coppin State University. Surrounded by greenery, showered with federal, state, and local money, Sandtown nevertheless became an endogenous transmitter of poverty and violence. After a half-century of federal efforts, and despite the traditional Christian preaching of its ministers, West Baltimore remains largely bereft—peopled, in the words of New Jersey pastor Buster Soares, by numerous caterpillars who will never molt into butterflies without a transformation of values.

The riot ideology of the 1960s had been about cadging federal funds under threat of violence; the riot ideology of 2015 is about the smoldering resentment that led the underclass and its media and political enablers to argue that racist cops produced depraved urban behavior. David Simon, the idiot-savant creator of HBO’s award-winning The Wire, which glamorized Baltimore’s black drug “crews,” blamed the legacy of O’Malley’s quality-of-life policing for the riots. Simon described Baltimore police officers as “an army of occupation.” He unintentionally had a point. The police, despite their vices, impose a modicum of conventional values on a polity where the culture of gangsta rap projects the illusion of a revolutionary alternative to “bourgeois white values.” An MSNBC host plausibly compared inner-city Baltimore with the Gaza Strip, where the failure of repeated self-destructive assaults on Israel hasn’t diminished the illusion that the Jewish state is but a passing phenomenon of settler-colonialism.

After the Ferguson riots of 2014, disdain on the street for Baltimore’s integrated but often less than professional police department became combustible, and Gray’s death lit the powder keg. Economically marginal residents—in a city home to Johns Hopkins University and financial firms Legg Mason and T. Rowe Price—perpetrated Baltimore’s spring 2015 riots, which destroyed 200 businesses and injured 98 cops. The trouble began at the James Rouse–constructed Mondawmin Mall. Students, angry at the way they were “disrespected” and inspired by the sci-fi movie The Purge, which described a day of seemingly emancipatory anarchy, gathered outside the mall’s transportation hub. Flyers called for the Crips, the Bloods, the Black Guerrilla Family, and the Nation of Islam to unite and join the action. Students cornered by cops reportedly began taunting police, who had gone on alert after receiving what the department called “credible information” that a coalition of gangs wanted to “take out” law-enforcement officers. Rioting ensued.

Reporters took little notice of these gang elements, since the liberal media operated on the principle of “implied suffering”—that is, people acting badly is de facto proof that they have been mistreated. The persistence of poverty in West Baltimore supposedly demonstrated pervasive white racism and black powerlessness. Yet the same Black Guerrilla Family was powerful enough to have run the Baltimore City Detention Center until Maryland governor Larry Hogan shut it down.

As the violence unfolded, Mayor Rawlings-Blake told police to stand down. “I’ve made it very clear that I work with the police and instructed them to do everything that they could to make sure that the protesters were able to exercise their right to free speech,” she explained. “It’s a very delicate balancing act, because while we tried to make sure that they were protected from the cars and the other things that were going on, we also gave those who wished to destroy space to do that as well.” And, she said, “we worked very hard to keep that balance and to put ourselves in the best position to deescalate, and that’s what you saw.”

Baltimore is a city of many Freddie Grays. The 25-year-old Sandtown resident, a petty drug dealer who had been arrested 18 times, might have seemed like a flawed martyr. His death appeared to be the result of police negligence—he wasn’t fastened into a seat belt for the 45-minute ride to the police station and suffered a severe spinal-cord injury—rather than intentional malice. But in a city where one in ten residents is a drug addict, and in a state where ex-felons can vote, Gray represented a significant constituency. Showing, she said, that “no one is above the law,” state’s attorney Marilyn Mosby brought murder charges against the police less than two weeks after Gray’s death. “To the people of Baltimore and the demonstrators across America: I heard your call for ‘No justice, no peace,’ ” she said. “Your peace is sincerely needed as I work to deliver justice on behalf of this young man.”

Mosby’s husband, a city councilman representing West Baltimore who has mayoral ambitions, gently described his rioting constituents as engaged in “a cry for help.” The rioting and looting had “nothing to do with West Baltimore or this particular corner in Baltimore,” Nick Mosby told a reporter. But Leland Vittert of Fox News stood with Mosby outside a West Baltimore liquor store as it was being looted, and the councilman refused to criticize the thieves. Looting, Mosby said, is “young folks of the community showing decades-old anger, frustration, for a system that’s failed them. I mean, it’s bigger than Freddie Gray. This is about the social economics of poor urban America.” It’s also about drugs and the unprecedented mass theft of opiates by many of the city’s gangs. According to the Associated Press, federal drug-enforcement agents said that Baltimore gangs targeted 32 of the city’s pharmacies during the riot, stealing roughly 300,000 doses of opiates such as oxycodone. “The ones doing the violence,” said a 55-year-old West Baltimore woman, were “eating Percocet like candy and they’re not thinking about consequences.”

“Justice for Freddie Gray” produced a withdrawal of law and order. The “army of occupation” retreated, murders surged, and thugs roamed the streets largely unhindered. The protest culture of the sixties ruled the day but without the hope once engendered, albeit mistakenly, by the incidents of that era. Great Society–inspired social programs failed to reduce poverty but succeeded in creating self-serving political machines that blame white conspiracies for the degradation of West Baltimore and other urban areas.

Mayor Rawlings-Blake called in Al Sharpton and fired police chief Anthony Batts, who had tried to upgrade the police department but became the fall guy for the mayor’s failings. Baltimore today is demarcated by white enclaves and by those African-American areas defined by the gangsta rap culture where, in a parody of the segregated South, honor is all and disrespect requires the “satisfaction” of personally delivered revenge. But while the streets have been ceded to thugs in those neighborhoods, it’s not politically acceptable in Baltimore to describe rioters in such terms. At the height of the protests, when the mayor announced that the National Guard would be deployed and a citywide curfew imposed, she also referred to the rioters as “thugs.” She was then forced to apologize for her candor, reclassifying the miscreants as “misguided young people.”

For Ta-Nehisi Coates, the crews and the gangsta rappers singing about the need to “Fuck the Police” are preferable to the cops. The cops, complains Coates, “lord over” young black men with “the moral authority of a protection racket.” There is a touch of truth in this. But, Coates goes on, the problem with the police “is not that they are fascist pigs but that our country is ruled by majoritarian pigs.” The solution, he implies, is a black population released from the ideals of the American dream and from the “false morality” of white Americans. For Coates, blacks can only be freed from racism after whites have been emancipated from capitalism.

A man, a city, a movement, and a moment have met: West Baltimore has, for the time being, been liberated from American morality. Let’s judge Coates’s vision on how that plays out.

The death of Freddie Gray ignited Baltimore’s spring 2015 riots (Top Photo, (Branden Eastwood/Reux)), which pitted police against inner-city protesters (Second Photo) in a reprise of Baltimore’s late sixties racial confrontations (Third Photo).