The heart, if not the soul, of Spain’s capital, Madrid, is its bustling financial district. Thousands crowd daily into the skyscrapers that overlook the district’s main square. Thousands more shop at a branch of El Corte Inglés (Spain’s Macy’s), attend soccer games at Bernabéu Stadium, or ride the subways, trains, and buses whose lines converge here.

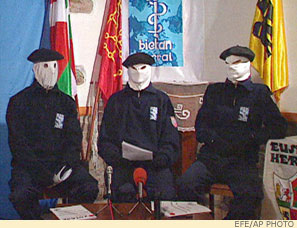

Terrorists had hoped to strike this densely packed urban space in early 2008. But unlike the devastating coordinated suicide bombings of March 11, 2004, which killed 191 train commuters and wounded 1,600, this plot did not originate with al-Qaida or any of its loosely linked affiliates. Nor was it hatched among the 12 militant Muslim Pakistanis arrested in January for allegedly planning suicide bombings in Barcelona’s subways and other strikes in Britain, France, Germany, and Portugal. No, the terrorists who dreamed of creating mayhem in the square were as Spanish as paella, as much a part of the local landscape as flamenco or bullfighting: “Euskadi Ta Askatasuna,” or “Basque Homeland and Freedom,” commonly known as ETA (pronounced “etta”). This is Spain’s “other” terrorism—a Marxoid movement that, for some 50 years, has fought for independence for the 2.5 to 3 million Spaniards of Basque descent.

Though no specific date for the financial-district attack had been set, Spanish law enforcement officials said that two arrested ETA militants confessed to planning to detonate a bomb-filled car in the square’s vast underground parking lot or in one of its surface lots at some point before Spain’s March national election. Several officials doubted that the plot would have succeeded, but the suspects were among those who staged the December 2006 bombing of Terminal 4 at Madrid’s Barajas Airport, which killed two and leveled the gigantic structure. ETA had already hidden some explosives for the new strike in the semi-Basque region of Navarre, police disclosed, and maps of the square and its parking lots turned up in one suspect’s apartment.

Because most of the world has focused on al-Qaida and its allied groups, it’s easy for outsiders to overlook the continuing danger of ETA—a seemingly anachronistic “national liberation” force in an ever more globalized world. In 2007, ETA managed to kill only five people. But over the last three decades, its attacks have claimed over 830 lives, and its ongoing commitment to violence has provided leverage to the separatist politicians associated with the Basque “cause,” even as they denounce terrorism. Angry exchanges about ETA dominated part of the preelection debates this spring between Socialist prime minister José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero (the eventual winner) and his rival, Mariano Rajoy of the conservative People’s Party; al-Qaida went virtually unmentioned. Shortly before the election, ETA reminded Spaniards of its brutal presence yet again, gunning down a former city councilman in front of his wife and child in Arrasate, a working-class town in the Basque Country.

The roots of Spain’s ETA problem are in the country’s tormented past. As British journalist Giles Tremlett observes in his 2006 book The Ghosts of Spain, many Spaniards see their country as merely a state that has imposed its will on several other nations—among them Euskadi, as the Basque Country is now officially called; Catalonia, which has its own (nonviolent) separatist movement; and Galicia. In these regions, which account for a quarter of Spain’s population, Tremlett writes, “the word España is often unmentionable.” History can be a political battlefield here. For example, while most Spaniards and the rest of the planet consider Magellan the first person to have circumnavigated the globe, every Basque student knows that the honor goes to Juan Sebastián Elcano, a Basque sailor who assumed command of Magellan’s ships after the Portuguese navigator’s death in 1521. A major street in Bilbao, the Basque Country’s largest city, bears the local hero’s name.

ETA’s dream is to unite the Basques of Spain and northern France into an independent nation. Never mind that Spain conquered and absorbed Navarre, the site of the last Basque-dominated kingdom, back in 1512; or that two-thirds of Navarre’s population are no longer purely Basque; or that polls consistently show that majorities there and in the three Basque provinces (which, unlike the region of Navarre, are overwhelmingly Basque) want to remain part of Spain. ETA argues that time hasn’t healed the historical injustice of the Basque Country’s incorporation into Spain and that the Basques must return to their own traditions. (Some historians maintain that the Basques may stretch back as far as 5,000 years, making them Europe’s oldest people with its oldest language, a unique tongue called Euskara.)

Juan Pablo Fusi, former head of the National Library of Madrid and an authority on the Basque Country, points out that Basques look no different from other Spaniards and were never a nation, though they’ve had a strong sense of national identity since at least the sixteenth century. Basque nationalists have relied on a largely invented history to justify their claims, charges José Martínez Soler, who runs 20 Minutos, a free newspaper in Madrid. “ETA plays off the widespread nostalgia among Basques for something they never had—an independent Basque country,” he says.

Both men agree that ETA, founded as a Marxist-Leninist group in 1959, gained popularity from fighting Generalissimo Francisco Franco, the dictator who ruled Spain from the thirties until his 1975 death. But ETA’s war continued even as King Juan Carlos I oversaw Spain’s transition to democracy, which culminated in 1978 with a constitution that granted considerable autonomy to Spain’s 17 regions and 50 provinces. A year later, some nationalist parties associated with ETA declared that the degree of autonomy was insufficient and began championing an independent Basque state. Over time, the list of ETA targets expanded from the Civil Guard (one of Spain’s three main police forces and the one that did most of the Franco regime’s dirty work) and the state’s military personnel to judges, lawyers, teachers, businessmen, writers and other intellectuals, and even Basque nationalists who opposed independence.

The Spanish government responded with an equally ugly “dirty war” against ETA called GAL—Grupos Antiterroristas de Liberación—a secret government-sponsored campaign from 1983 to 1987, in which death squads killed, kidnapped, and tortured not only alleged ETA members but also civilians who, it turned out, had nothing to do with the group. In 1997, a Spanish court convicted several officials, including a former interior minister in the government of Socialist prime minister Felipe González, on charges related to the illegal campaign. Disclosure of GAL in a country with Spain’s history of government oppression generated sympathy for ETA that it otherwise would have lacked because of its own violence.

Eduardo Uriarte Romero knows too well why ETA remains a threat: he once belonged to it. One of 16 ETA guerrillas put on trial for the 1968 murder of a police chief, he is alive today only because the trial sparked huge protests among Basques, which led Franco to commute his two death sentences to 169 years in jail. Freed by a general amnesty in 1977, Uriarte says that he quit ETA after Spain became a democracy and the Basque region became semiautonomous. “Some in ETA argued that we had to go on after Franco’s death, that nothing had changed. But clearly, that was not true,” he notes, reminiscing over coffee at a Bilbao hotel with other former ETA members. “Since 1978, Madrid’s legal reach over us here in the Basque Country is marginal at best.”

Indeed, the Basque Country now boasts its own flag and national anthem, as well as its own health, security, and tax systems. “The Basque government collects nine out of every ten [tax] euros in the region. We have 7,500 cops and our own parliaments,” Uriarte points out. The Basque provinces also have their own Euskara-language public schools now—some 80 percent of the state schools in the region—which are teaching children a language that many of their parents don’t know. A 2001 poll found that only half of all Basques could speak or understand the old tongue; even the Basque president, Juan José Ibarretxe, had to learn Euskara after assuming his post.

Now a leader of the Foundation for Liberty, a pro-democracy Basque organization that champions democracy and civil liberties and opposes ETA and other violent groups, Uriarte argues that ETA delegitimized itself in the early eighties when it began to target Basque nationals who opposed independence. “Suddenly, anyone and everyone became fair game,” he says. The number of victims increased dramatically as ETA’s targets broadened. “From its start through the 1960s, 77 people were killed,” observes foundation vice president Javier Elorrieta García. “After the transition [to democracy], that number shot up. Today it is nearly 900.”

ETA’s stock-in-trade is less political murder than ongoing intimidation. ETA, like the Mafia, finances its operations mostly through extortion. “You get a typed letter, almost a form letter, at your business or home, saying that the time has come to do your patriotic duty and pay your ‘revolutionary tax,’ ” Elorrieta explains. “They demand between 30,000 and 300,000 euros, depending on the size of your company. If you don’t pay up, you get a second letter, which contains a warning. Then you get a third, which gives you a date by which you must comply. You don’t get another after that.” Most victims find it safer to cooperate. Spanish law enforcement officials estimate that ETA raises some 3 million euros yearly, or $4.7 million, from such shakedowns.

Reinforcing public fear are the trained youth gangs that roam the streets of Basque towns, especially on weekends, randomly attacking shops, burning buses, and spray-painting ETA slogans on bridges, roads, and street signs. The gangs have provided ETA with recruits.

Terrorism analysts Rogelio Alonso and Fernando Reinares estimate that as many as 42,000 Basque citizens live under daily threat from ETA and its supporting gangs. Bodyguards have thus become a cottage industry in the Basque region. Uriarte and Elorrieta each have two: one accompanies his boss from home to work and on errands; the other, whose exact whereabouts are unknown, watches from a distance to ensure that no one is tailing his boss or readying a hit. As we drink our coffee, two muscular men in ill-fitting jackets and bulges under their arms sip theirs at a table nearby. Elorrieta waves to them; they wave back. Elorrieta estimates, and Spanish police in Madrid concur, that over 1,000 Basque citizens have had to hire such private protection.

Still, for all the repugnance at such violence and intimidation, ETA retains some public support in the three Basque provinces. In late January, in Bilbao, over 35,000 people protested the Socialist government’s punishment of a Basque politician who had refused to abide by a supreme court decision banning a tiny political party for its purported ETA ties. Walking leisurely through Bilbao’s pristine boulevards and converging on one of its main squares, many protesters wore the Barbour jackets and cashmere scarves so popular among Spain’s conservative upper class. A good number of the women, both young and old, sported designer handbags and expensive coifs. The crowd applauded politely as President Ibarretxe warned that any movement by Madrid against local parties would be seen as unacceptable meddling in the Basque Country’s internal affairs.

Elorrieta chuckles when I ask him the next day about the well-heeled rally. “The Basques of Spain are hardly politically and economically oppressed downtrodden masses,” he says. “They are wealthy compared to most other Spaniards. About 100,000 families have second homes.” In fact, the region has the highest per-capita disposable household income in the country, making any Basque tolerance of the Marxist-Leninist ETA all the more puzzling to outsiders. Part of the explanation is an odd kind of traditionalism, believes Juan Antonio Rivas Pérez, a former vice rector of the University of the Basque Country and a Foundation for Liberty activist. “Basque society is very conservative,” he asserts. “We are faithful to our brands,” whether of jam, ham, or political parties. So while ETA’s terrorism appalls many Basques, above all the young, Rivas says, it is “the terrorism we know. It is our terrorism.”

Other factors have enabled ETA to maintain a degree of public support. The Basques are among Spain’s most religious people, for instance, and the local Catholic Church’s stance toward ETA was for a long time less than oppositional. “Until a decade ago, many priests would pass the hat for ETA each Sunday,” recalls Uriarte. (A Basque priest or other church leader would usually be present during the government’s open and back-channel negotiations with ETA over the decades.) Further, what historian Fusi calls “a reaction against modernity” has fueled the Basque nationalism that underpins ETA. Since the advent of democracy, Spain has been galloping toward globalization, and its economy in recent years has boasted some of Europe’s highest growth rates, bringing massive changes and upheavals along with the prosperity; many Basques are nostalgic and think that independence would preserve their way of life. Finally, the Basque Country’s nationalist political parties have found ETA’s continued presence useful as leverage in getting concessions from Madrid—“Either go along with our demands for autonomy, or the violence might get worse”—and so have lent the group a veneer of legitimacy.

Consider Marian Beitialarrangoitia, the mayor of the Basque town of Hernani. At the rally, she charged the Socialist government with bullying fellow Basques and her party, Basque Nationalist Action, to court voters in the national election. Earlier, she had accused the police of torturing one of the two suspects arrested in the 2006 Madrid airport bombing—charges the police deny—and infuriated many Spaniards by asking for the “warmest possible applause” for both suspects. ETA, she told me in an e-mail, was not to blame for the violence; rather, it was the “direct consequence of the political conflict” and the government’s “continuing refusal . . . to recognize the existence of the Basque nation and a rejection of the right to self-determination.”

The good news about ETA is that it has lost enormous ground. The results of the latest national elections this March show that public opinion in the Basque provinces is hardening against independence. Ibarretxe’s nationalist party lost roughly a quarter of the votes that it won in 2004, while support for a splinter party also pushing independence fell even more sharply—from 81,000 votes last time to just 50 this year. Despite ETA’s call for an election boycott, seven out of every ten Basques went to the polls. ETA’s murder of the former councilman, a Socialist, two days before the election apparently prompted a large sympathy vote for the Socialists, who won a second term with an expanded majority.

Basque antipathy toward ETA itself is growing, too. According to a study by terrorism experts Alonso and Reinares, nearly half of Basque adults surveyed in 1978 saw ETA members as either “patriots” or “idealists,” and only 7 percent described them as “criminals”; by 2004, 69 percent of Basques surveyed regarded ETA’s militants as “terrorists,” with 17 percent describing them as criminals or murderers. Part of the reason for this shift is surely al-Qaida’s targeting of Spain in the 2004 bombings. “It is al-Qaida that is helping to destroy ETA,” argues Jose Martínez Soler, the newspaper editor. “ETA does not know now what to do. It sees the revulsion of Spaniards to al-Qaida’s violence.”

Judge Baltasar Garzón, a prosecuting magistrate in Spain’s National Court, is a target for both ETA and militant Islamists, but he doesn’t seem to be a man who lives in fear. As his bodyguards patrol his armor-plated car outside Al-Mounia, a venerable Moroccan restaurant in downtown Madrid, Garzón nibbles calmly on appetizers of olives and ham. “ETA is a small problem in the world but a big problem in Spain,” he says in English that remains halting despite the year he spent at New York University’s King Juan Carlos of Spain Center, where he wrote a book about Spanish terrorism. “ETA is still the greater threat today, but al-Qaida is the threat of our future.”

Garzón takes issue with the small group of analysts who argue that al-Qaida and ETA have secret ties. “These groups occupy different worlds, different universes,” he says. “One is religious, the other secular; there is simply no connection between them.” Still, they are increasingly linked in the public mind. Even Garzón initially believed that ETA was responsible for the March 11, 2004, train suicide bombings, just as the conservative government of José María Aznar had charged. (Political analysts believe that in the national elections, held less than a week after the attacks, Aznar’s insistence that ETA was to blame—despite emerging evidence that pointed to North African jihadists attacking Spain for participating in the Iraq War—tipped the balance against the conservatives, who had held office since 1996, and for Zapatero’s Socialists.)

Earlier circumstantial evidence did point to ETA, Garzón says—ETA, for instance, had tried to blow up trains in Madrid several months earlier, and the Spanish national police had first believed that the explosives used on March 11 were identical to the Basque terrorists’ favored kind. Even Ibarretxe, the Basque president, initially blamed ETA, notes Garzón. But the judge, unlike Aznar, quickly changed his mind, especially after an ETA-linked newspaper denounced the attacks. “I thought: Why would ETA denounce its own attack? Then it turned out the explosives were different from those that ETA used. Finally, al-Qaida claimed responsibility.”

Another cause of ETA’s woes, argue Giles Tremlett and other analysts, is an increasingly aggressive judicial and law enforcement crackdown. Garzón, a controversial figure with many detractors, nevertheless receives widespread credit for forcing the Spanish government to take terrorism more seriously, and for striking the first truly effective blow against ETA when, in 2003, he ruled to suspend the activities of Batasuna, a Basque party that usually won 8 to 12 percent of the Basque vote. Batasuna was merely an ETA front, argued Garzón; his finding was upheld by Spain’s supreme court, which banned the party outright that year, stunning the country. The decision delivered what Rivas calls a “crushing blow” to ETA’s ability to operate on two fronts: secretly, through terror and criminal shakedowns; and openly, through Spain’s complex, fragmented political system. “The banning of Batasuna destroyed ETA’s myth of invincibility,” says Rivas. “It put ETA on the defensive for the first time.”

Spain has not only banned ETA-linked parties but also boosted arrests and prosecutions, cutting down on the number of terror victims. Police data show that the rate of ETA’s killings has dropped from 34 a year in the 1980s to single digits in the new millennium. Tremlett says that the rate dropped fastest under Aznar, whom he credits with launching a counterterrorism campaign that included stepped-up surveillance and intelligence-sharing and police cooperation agreements with France and other nations—but without the extrajudicial killings, torture, and other human rights violations that Spain saw in the eighties. By the time Aznar left office, Tremlett says, ETA had gone almost a year without being able to kill anyone—a first. Spanish law enforcement officials estimate that there are now no more than 150 trained ETA commandos hiding in Spain and France; Garzón thinks that there may be as few as 70. “This is the weakest ETA has ever been in its almost 50-year history,” says analyst Reinares.

Unfortunately, Prime Minister Zapatero’s decision in 2006 to negotiate with ETA without demanding that it first lay down its weapons proved a major miscalculation, threatening to reverse these gains. While ETA had entered into and broken temporary cease-fires with previous governments in 1989 and 1998, the Socialists had claimed, with much fanfare, to have brokered Spain’s first “permanent” cease-fire with the group. But the lull in terror lasted only eight months, shattering in December 2006 with ETA’s airport attack. Though ETA had phoned in a warning, as it often does, two Ecuadorans, sleeping in their car while waiting to pick up passengers, died in the blast. The Socialist government suspended talks and increased police and political pressure on ETA.

Terrorism experts now agree that ETA simply used the cease-fire to rebuild, recruit, and rearm. Three months before the rupture, a mysterious group, now believed to have been ETA, stole 350 pistols from a gun store in Vauvert, a town in southeastern France. (ETA commandos have long sought refuge and logistical support in France.) And the group shows signs of new life. Last June, Spanish Civil Guards discovered detonators, timers, a bomb-making manual in Euskara, and over 220 pounds of explosives in an abandoned car in southern Spain, near the border with Portugal, where ETA is believed to have tried to establish a base. Then, in December, ETA gunned down two unarmed members of a joint French-Spanish police task force in a supermarket parking lot in southern France. The killings have intensified cooperation between French and Spanish police. Law enforcement officials say that some 40 ETA suspects have been detained in France and Spain since the end of the cease-fire, thanks in part to the mutual support.

Can ETA be totally eradicated? Spanish analysts disagree. Only a few maintain that Spain’s counterterrorism community can deliver a knockout blow to such a deeply entrenched group, which retains a shrinking but persistent reservoir of Basque public sympathy. Tremlett is among those who think that a political solution is essential. He argues that permitting the Basques a referendum on separation from Spain would undermine the nationalists’ claim that Madrid is denying the Basque Country the right of self-determination. But it is unlikely that any Spanish government—Socialist or conservative—would tolerate such a move, believing that it would reward ETA and set an unwelcome precedent for other challenges to Spain’s constitution. “Hold a plebiscite under terrorist threat?” asks Reinares rhetorically. “Would you accept that in Florida or California?” The most likely scenario is that ETA will endure, but diminished, inflicting a low but perhaps politically tolerable level of violence.

Despite Spain’s progress against ETA, many Spanish and American terrorism analysts and law enforcement officials remain deeply concerned about the country’s overall counterterrorism efforts. What one expert called Madrid’s “terrorism tunnel vision”—its understandable obsession with ETA—has allowed the international jihadist threat to take root and grow in Spanish soil.

The Spanish police and intelligence services have made terrible mistakes in the anti-jihadist struggle. Many of the North Africans responsible for the March 2004 railway bombings, for example, had been under surveillance prior to the attack. But Spain’s competitive police and intelligence agencies failed to share key information that might have prevented the strike—or at least the escape of key players afterward. Though Spain’s arrest of the militant Pakistanis last January disrupted the alleged suicide bombing plot, French authorities were furious when their Spanish counterparts disclosed the presence among the conspirators of a French-run confidential informant. Furthermore, though the informant had warned police that the terrorists were close to striking, the plot, between 18 months and two years in the making, was only at the “mid-stage” of development when Spanish police moved, say law enforcement officials. Neither the attackers nor the facilitators were fully in place, and the plotters had yet to manufacture or acquire the explosives that they required. (While it was initially reported that the plotters had acquired explosives for the mission, the substance that the Civil Guard found near them tested negative.) The presumed financier of the operation wasn’t arrested and presumably remains at large.

American intelligence and counterterrorism officials have repeatedly traveled to Madrid, American officials say, to urge the Spanish government to close loopholes that international terrorists have exploited in its legal system, reduce the self-defeating envy among Spain’s warring police forces, improve police training, and step up bilateral and multilateral counterterrorism cooperation. Some of this has occurred. Spain recently approved the stationing of an NYPD detective in Madrid to monitor counterterrorist operations. But most U.S. pleas have had limited impact, perhaps hampered by the tension between Washington and Madrid over Iraq and other issues.

For good reason, Spain has proved reluctant to return to anything that might remotely recall the Franco era’s dictatorial rule. So the nation’s antiterror campaign is deliberately low-key. Spanish police don’t carry machine guns or other heavy weapons on streets or at railway stations and airports. Police resist conducting random searches, even in areas with a history of attacks. Spain has no equivalent of the FBI’s Joint Terrorism Task Forces, which combine federal, state, and local police; coordination and communication among police and intelligence agencies are notoriously episodic. “Life” sentences of 40 years for terrorism—there’s no death penalty in Spain or anywhere in the European Union—often wind up being far shorter. Some of those arrested in antiterrorist raids are soon out on the street again, and worse, quickly go into hiding.

“Many rightists still believe that the only real terrorism threat facing Spain is from ETA,” says Reinares. “And many Socialist supporters have persuaded themselves that the threat of international terrorism has been dramatically reduced because Spain has withdrawn its troops from Iraq.” Thus, he says, “the jihadist threat has not been placed as high on our political agenda as I think it should be.” The foiled subway bombing plot and detentions last December in Barcelona demonstrate the seriousness of the threat, he adds. “But the incident did not create much anxiety here or put international terrorism at the center of our political debate. Spain will have to face it—eventually.”