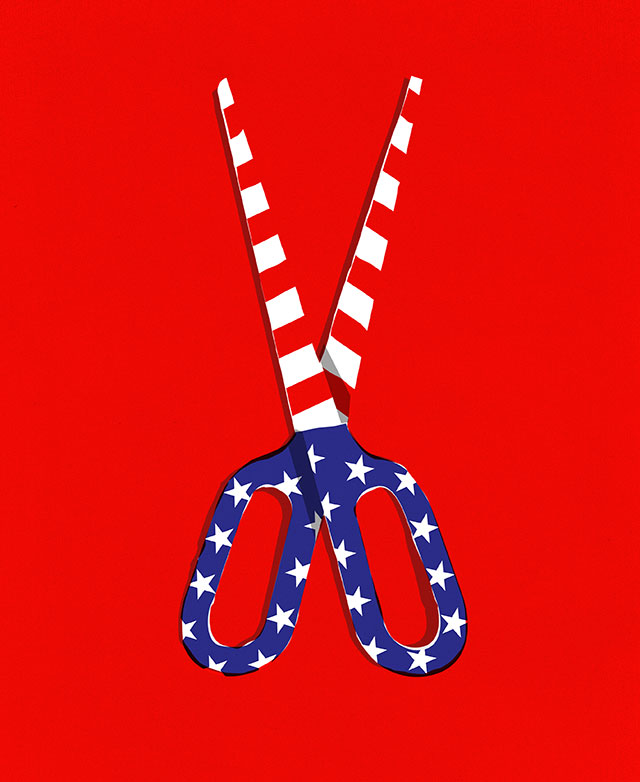

At a December 2017 press conference in the White House’s Roosevelt Room, President Trump boldly announced that his administration had begun “the most far-reaching regulatory reform in American history.” With typical flair, the president wielded a large pair of gold scissors, slicing red tape connecting piles of paper that symbolized the growth of the regulatory state. The smaller set of four stacks of paper was labeled “1960s”; the larger set, of five stacks, which towered over the president’s 6’3’’ frame, was labeled “TODAY.” The federal regulatory code had expanded from 20,000 to 185,000 pages over that period, Trump explained. “The never-ending growth of red tape in America has come to a sudden, screeching and beautiful halt,” he said.

Hyperbole aside, the administration’s early record on deregulation is impressive. In one of his first actions, Trump issued Executive Order 13771, directing the government to eliminate two regulations for each new one created. Since then, the executive branch has scaled back the rate of rule creation significantly, in comparison with the Obama years, in addition to slowing down or blocking many Obama-era rules. Some of the administration’s regulatory changes—such as the approval of the Keystone XL and Dakota Access pipelines—will have significant economic impact.

Yet Americans worried about the regulatory state are bound to be disappointed, at least absent major congressional action, and not just because the president’s team will be unable to deliver on his promise to pare back the federal regulatory code to “less than where we were in 1960.” At a press briefing later the same day, Neomi Rao, chief architect of the White House’s regulatory-rollback efforts as administrator of the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs, clarified that “returning to 1960 levels . . . would certainly require legislation.” The central challenge in reforming the modern regulatory state is that it has been built by, and is sustained by, multiple forces. What I call the four forces of the regulatory state—regulation by administration, prosecution, and litigation; and progressive anti-federalism—operate mostly independently of Congress, notwithstanding the legislative branch’s constitutional power to “regulate Commerce . . . among the several States.” To a significant degree, each force operates independently of oversight by the elected president as well. These forces both complement and interact with one another, frustrating ambitious reformers.

The first force, regulation by administration, is that most closely under Rao’s purview—though many administrative agencies are, by design, “independent” of presidential oversight. Congress delegates these agencies vast rule-making powers—they can craft regulations with civil and criminal sanctions, across the full scope of authority that the Constitution assigns to the legislative branch. Those powers are virtually all-encompassing today, notwithstanding their limited nature in the Constitution: under the Court’s 1942 decision in Wickard v. Filburn, the power to regulate interstate commerce extends even to a farmer’s decision to grow his own crops for his own consumption, because such activity might “affect” the national economy. And under a different set of Supreme Court precedents—Chevron v. Natural Resources Defense Council (1984) and Auer v. Robbins (1997)—courts “defer” to administrative-agency interpretations of laws that Congress drafts to empower them as well as of the regulations that they craft themselves. Thus, the modern administrative state collapses the separation of powers to a single nexus; agencies write their own rules, interpret them, and enforce them, largely insulated from the democratic process.

The volume of regulations and rules generated by the administrative state is mind-boggling. Notwithstanding its deregulatory zeal, the Trump administration in its first year promulgated 3,281 new rules, filling 61,950 pages of the Federal Register—though a good number of these new rules originated in the Obama administration. And the 3,281 new rules represented the fewest generated in any year of the four preceding presidential administrations; the number of new pages was the lowest since Bill Clinton’s first year in office, in 1993.

This modern state of affairs is antithetical to the system of government established by the Constitution. In its 1892 decision in Field v. Clark, the Supreme Court declared: “That Congress cannot delegate legislative power to the President is a principle universally recognized as vital to the integrity and maintenance of the system of government ordained by the Constitution.” The principle derives from a maxim articulated by John Locke in his Second Treatise of Government, well-known to the Founding Fathers: “The power of the legislative being derived from the people by a positive voluntary grant and institution, can be no other than what the positive grant conveyed, which being only to make laws, and not to make legislators, the legislative can have no power to transfer their authority of making laws, and place it in other hands.”

In its 1928 decision in J. W. Hampton, Jr. & Co. v. U.S., the Supreme Court opened the door to such transfers of authority, upholding the “flexible tariff provision” of the Tariff Act of 1922, which permitted the president to adjust tariff rates based on international price differentials. Writing for a unanimous Court, Chief Justice William Howard Taft opined that a legislative delegation of authority is permissible if Congress sets down an “intelligible principle to which the [executive branch] is directed to conform.” But seven years later, in a pair of 1935 cases (Panama Refining Co. v. Ryan and Schechter Poultry Corp. v. U.S.), the Court applied the nondelegation doctrine in overturning two provisions of the National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933; as the Court wrote in Panama Refining, Congress had not “declared or indicated any policy or standard to guide or limit the President when acting” under its delegation.

Panama Refining and Schechter Poultry are judicial anomalies, however. The Supreme Court quickly reversed course and rubber-stamped the rest of the New Deal; and never since has the Supreme Court stricken a congressional enactment on nondelegation grounds. When presented with an opportunity to revive the doctrine in considering Congress’s open-ended delegation of authority to the United States Sentencing Commission to set legally binding “sentencing guidelines” affecting all federal criminal defendants, in Mistretta v. United States (1989), the Court demurred. (The Court has since cut back on the legal force of federal sentencing guidelines, under a different rationale.) Writing alone in dissent, Justice Antonin Scalia warned: “By reason of today’s decision, I anticipate that Congress will find delegation of its lawmaking powers much more attractive in the future. If rulemaking can be entirely unrelated to the exercise of judicial or executive powers, I foresee all manner of ‘expert’ bodies, insulated from the political process, to which Congress will delegate various portions of its lawmaking responsibility.”

Scalia’s warning proved prescient. The delegation of congressional lawmaking power to politically insulated agencies reached its apotheosis in the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), a regulatory body set into motion by the 2010 Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, which was enacted in the wake of the financial crisis. The Dodd-Frank statute made the CFPB fundable through the Federal Reserve System—thus outside congressional appropriation authority. Its director was removable only for “good cause”—thus outside presidential oversight. In short: to execute the mundane task of generating and enforcing rules about whether banks and credit-card companies are bilking their customers, Congress set up a regulatory body essentially uncontrollable by the elected branches of government.

The absurd nature of this new entity became evident in the legal aftermath of a Washington scene that resembled an old Hollywood screwball comedy. On the Monday after Thanksgiving 2017, two people showed up at the CFPB’s headquarters at 1700 G Street, each purporting to run the agency. Mick Mulvaney, Neomi Rao’s boss as director of the White House Office of Management and Budget, entered the CFPB offices carrying a bag of doughnuts for the staff. At 7:56 A.M., he tweeted a picture of himself “hard at work” as acting director of the agency—a role to which President Trump had appointed him. A minute later, another government official, Leandra English, sent an e-mail to staffers, signing it as “acting director” of the CFPB. Three days earlier, the departing CFPB director, Richard Cordray, an Obama appointee, had named her deputy director.

“Agencies write their own rules, interpret them, and enforce them, largely insulated from the democratic process.”

Mulvaney’s claim to head the agency rested on the 1998 Federal Vacancies Reform Act, which empowers the president to fill temporarily vacant executive-officer positions with other executive officers already confirmed by the Senate (as Mulvaney had been). English’s claim, asserted in a federal lawsuit, was based on a Dodd-Frank provision that designated the deputy director to serve as acting director “in the absence or unavailability of the Director” of the agency. The Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel and the general counsel of the CFPB agreed with Mulvaney’s claim, as did the first federal judge to examine the case, but litigation remains pending. English and the proponents of her claim advocate a remarkable theory: “Congress determined that [the CFPB] needed to be an independent regulator—insulated from direct presidential management and control.” What would seem a defect under the Constitution is viewed, in the modern world of administrative law, as a feature, not a bug. Little wonder that it’s hard for any presidential administration to stem the regulatory tide.

The second force of the regulatory state, regulation by prosecution, is fed by and reinforces the first. Many administrative-agency regulations impose de facto criminal penalties, by broad grants of statutory authority. By establishing crimes in addition to civil offenses, federal agencies have assumed for themselves criminal lawmaking authority and vested federal prosecutors in the Justice Department with a shadow regulatory power that runs parallel to the agencies’ own administrative enforcement.

This development is of major consequence. The American Revolution was born in part from colonists’ objection to “taxation without representation.” Our modern federal government is engaging in large-scale “criminalization without representation.” Scholars estimate that more than 300,000 federal crimes are on the books—but 98 percent of them were never voted on by Congress. Thus, American citizens face a plethora of potential criminal charges with possible prison sentences for offenses drafted without the input or oversight of elected representatives.

The Bill of Rights is largely concerned with procedural protections from overzealous criminal prosecutions. But in the context of the modern shadow-regulatory state, these constitutional strictures afford little solace to those in prosecutors’ sights. That’s because the long-standing rule of legality (the principle that the criminally accused must be put on notice of their crimes) becomes inoperable when the list of crimes numbers in the hundreds of thousands and the government can change its interpretations of the rules, with judicial deference. In the context of the regulatory state, the courts have tossed aside the traditional requirement that a criminal have a “guilty mind” (mens rea) in addition to committing a “guilty act” (actus reus).

The nation’s highest court began eroding this protection nearly a century ago. In 1922, in U.S. v. Behrman, in which it upheld a criminal conviction under the Harrison Narcotics Tax Act of 1914, the Court decided that criminal intent was not required, unless specified, for statutory crimes. Twenty-one years later, in U.S. v. Dotterweich, a divided Court pushed this principle further in upholding the conviction of a pharmaceutical company president under the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906 for an employee’s illegal shipment of drugs—notwithstanding the absence of a claim that the president had knowledge of such shipment and the absence of any clear statutory authorization for such a charge. In dissent, Justice Frank Murphy objected: “It is a fundamental principle of Anglo-Saxon jurisprudence that guilt is personal, and that it ought not lightly to be imputed to a citizen who, like the respondent, has no evil intention or consciousness of wrongdoing.”

In 1952, a unanimous Supreme Court reaffirmed this principle in Morrisette v. U.S., when it overturned the conviction of a junk dealer who had sold rusted-out, spent air-force bomb casings, believing them abandoned: “The contention that an injury can amount to a crime only when inflicted by intention . . . is as universal and persistent in mature systems of law as belief in freedom of the human will and a consequent ability and duty of the normal individual to choose between good and evil.” But the Court based its decision on the fact that the statutory crime in question involved conduct akin to “[s]tealing, larceny, and its variants and equivalents”—common-law crimes that were “among the earliest offenses known to the law,” as opposed to modern “public welfare offenses” created solely by statute. The modern legal rule thus turns the old criminal-law principle on its head and allows the government to treat the accused as strictly liable for criminal offenses that are wrong not intuitively but only because of the government’s mandate (malum prohibitum).

In practice, this means that well-meaning individuals are easily ensnared—and made criminals—by the modern regulatory state. Take, for example, the case of Lawrence Lewis, who grew up in the projects of Washington, D.C., and worked his way from school janitor to chief engineer at a military retirement home. In 2007, he became a federal criminal. When the home under his charge, full of sick veterans, was flooded, Lewis diverted a sewage backup into a storm drain that he believed led to the sewage-treatment plant. Unfortunately, the drain instead led to a creek, which fed into the Potomac River. Lewis was charged with a criminal environmental infraction that did not explicitly require prosecutors to prove criminal intent. It didn’t matter that he was only trying to help retired veterans in a crisis.

Regarding corporations and other complex enterprises, the modern criminal law has empowered federal prosecutors to act as super-regulators with even fewer constraints than those that bind administrative agencies. In its 1909 decision in New York Central Railroad v. U.S., the Supreme Court determined that it was within Congress’s constitutional power to impute the criminal acts of employees to a corporate employer. Today, U.S. corporations can be found criminally responsible for the misdeeds of lower-level employees, even when the employees’ actions contravened clear proscriptions from senior management and evaded corporate-compliance programs—a broad concept of corporate criminal liability that goes well beyond that in most other developed countries.

The easy attribution of criminal liability to corporations and the scope of the federal regulatory criminal law make any large business enterprise a likely criminal. And the harsh collateral consequences that conviction or even indictment typically portend for corporate defendants generate inexorable pressure on companies to capitulate to prosecutors’ demands, once in the government’s crosshairs. These consequences include debarment from government contracts, exclusion from reimbursement under government-run health programs, and loss of operating licenses. Such penalties would constitute an effective corporate death sentence for most companies facing prosecution—as demonstrated when the former Big Five accounting firm Arthur Andersen was indicted in 2002 for employees’ bookkeeping for the defunct energy firm Enron. Following the indictment, the firm quickly collapsed; that the Supreme Court overturned the accountancy’s conviction (U.S. v. Arthur Andersen, 2005) offered little solace to its displaced employees, customers, and creditors.

The threat to businesses posed by potential criminal prosecution has enabled federal prosecutors to extract billions of dollars annually and to modify, control, and oversee corporate behavior in ways unauthorized by statute—without ever taking the companies to court, with no substantive judicial review, and with no transparency to the public and lawmakers. Since 2010, the federal government has entered into coercive pretrial diversion programs with innocuous-sounding names—“deferred prosecution agreements” and “non-prosecution agreements”—with hundreds of domestic and foreign businesses, including more than one-sixth of America’s Fortune 100.

Among the changes that the Justice Department has required of companies through these agreements are firing key employees, including chief executives and directors; hiring new C-Suite corporate officers and corporate “monitors” with access to all layers of company management and who report to the prosecutor; modifying compensation plans and sales and marketing practices; and limiting corporate speech and litigation strategies. No such changes to business practice are authorized by statute. Nor would such punishments be available to the government after a corporate conviction. In some cases, the government is using these agreements to sidestep constitutional limits on government power—as when prosecutors have strong-armed companies into waiving their own or their employees’ First Amendment rights to free speech, Fourth Amendment protections against illegal searches and seizures, Fifth Amendment rights against self-incrimination, and Sixth Amendment rights to counsel.

The third force of the regulatory state, regulation by litigation, predates the U.S. Constitution, being largely a feature of state tort actions inherited from English common law. To some degree, the power of this force in American regulation owes to the shoehorning of old legal doctrines developed in a different era into a modern economic context to which they were ill-applied. Negligently breaking a friend’s cask of brandy while moving it from one cellar to another—the allegation in the famous 1703 British case Coggs v. Bernard—bears little resemblance to modern asbestos litigation, which foists billions of dollars of liability on corporate defendants that never manufactured asbestos, a product itself long since banned (and the companies that originally made it long since bankrupt).

But the vast reach of U.S. civil litigation is no mere English law accident. Under our inherited rules, tort law would have remained the legal backwater it was when it was principally enforced to compensate individuals trampled by a neighbor’s horse. What we know as regulation through litigation was, once again, largely born out of changes in the New Deal era. That’s when Congress delegated the drafting of a new Federal Rules of Civil Procedure (adopted in 1938) to the dean of Yale Law School, Charles E. Clark; and when the Supreme Court decided to toss out more than a century’s worth of precedent of federal common law of tort (Erie Railroad Co. v. Tompkins, 1938)—and subsequently to allow plaintiffs to enforce jurisdiction against corporate defendants with “minimum contacts” in the state (International Shoe Co. v. Washington, 1945). These shifts, in combination with later federal rules (such as the “class action” rules permitting lawyers to initiate cases on behalf of thousands or even millions of clients) and historical anomalies (such as America’s idiosyncratic rule that a successful defendant in a lawsuit is not reimbursed legal fees), have produced a U.S. tort system roughly three times as costly as the European Union average, consuming almost 2 percent of gross domestic product. Its de facto regulatory impact is broader still.

What makes the tort system so tough to reform is that, applied to large-scale commerce, it often inverts the ordinary federalist structure. Federalism, in general, is one of the linchpins of America’s constitutional genius. By dividing power vertically as well as horizontally, federalism generally enables robust but limited government. The key feature of federalism is that it makes it possible for people and firms to “vote with their feet.” States with overreaching taxes and regulations—or those that have let their infrastructure and services atrophy—will lose people and businesses to states with the “right” government balance. Federalism thus tends to facilitate a “race to the top” among competing state polities. But federalism stops working when it becomes a “race to the bottom”—when one state can dictate the terms of national commerce.

Federalism in tort law works when its effects are mostly localized. A state that has overly loose laws permitting recovery for workplace accidents will, over time, have fewer workers to employ; and a state that permits undue recoveries in medical-malpractice claims will find that it has fewer doctors overall—and the inevitable higher health-care costs that result. But in other cases—those that most affect national commerce—states face little incentive to pare back abusive lawsuits. Under federal rules, a company making a product in Nebraska can generally still be sued for alleged product defects in California, so relocating from the Golden State to the Cornhusker State makes little difference.

“The U.S. tort system is roughly three times as costly as the European Union average, consuming almost 2 percent of GDP.”

This inverted federalism lets lowest-common-denominator state tort laws set the national regulatory bar—even if in significant conflict with federal regulations. In its 2009 decision in Wyeth v. Levine, a divided Supreme Court let stand a Vermont jury “failure to warn” tort-law verdict against drugmaker Wyeth for an adverse event caused by a pharmaceutical product. The drug in question, Phenergan, approved by the FDA in 1955, had been administered by a medical professional. But the adverse event was severe, and necessarily heart-wrenching for any jury: professional guitarist Diana Levine had to have her arm amputated below the elbow after developing gangrene. The physician’s assistant had inadvertently injected the Phenergan into the patient’s artery, rather than a vein.

As horrible as Levine’s injury was, the problem with holding Wyeth responsible for it was that the potential side effect of gangrene from arterial injection had long been known, and yet the FDA maintained that the product should remain available. And over a period of more than 20 years—from 1973 to 1997—the federal agency had worked with the manufacturer to develop the proper warning label. The label ultimately adopted for Phenergan contained four prominent notices of the risk of gangrene from arterial exposure, including, in two places, a simple, bold, uppercase warning: “INTRA-ARTERIAL INJECTION CAN RESULT IN GANGRENE OF THE AFFECTED EXTREMITY.”

To defenders of the regulatory state, tort cases like Wyeth’s serve as a useful adjunct to the federal administrative scheme, filling in the “gaps” of agency rule-making. But it’s an obvious one-way ratchet toward greater regulation. And the implicit tax imposed on a manufacturer can be levied by a single state—even if ill-founded, even if contrary to federal regulators’ judgment, and even if the other 49 states disagree. Consider lawsuits that have flooded the magnet courts in and around St. Louis alleging that baby-powder talcum causes ovarian cancer. Never mind that the American Cancer Society has broadly considered the long-available product to be safe. Never mind that the FDA found insufficient evidence to support even including a warning label on the product. In 2016 and 2017, St. Louis juries considering baby-powder lawsuits returned four verdicts totaling $307 million against New Jersey–based Johnson & Johnson on behalf of plaintiffs from Alabama, California, South Dakota, and Virginia. By the summer of 2016, among the 2,100 lawsuits nationwide alleging that talcum powder caused ovarian cancer, two-thirds were situated in the City of St. Louis Circuit Court.

If U.S. tort law is a mixed bag in terms of federalism, what I call progressive anti-federalism turns the concept on its head. To some degree, pushback by state and local officials against the federal government is natural, given that elected officials are bound to disagree. Former Texas solicitor general Ted Cruz and former Oklahoma attorney general Scott Pruitt rose to national prominence by challenging in the courts what they perceived as federal overreach. Progressive state officials are similarly challenging the Trump administration and the Republican Congress.

But in many cases, state officials are not merely challenging the legality of federal action but using the regulatory-state tool kit—civil litigation, the threat of prosecution, and administrative powers—to develop a final, and powerful, alternative locus of the regulatory state. State and local officials—most notably, but not exclusively, state and local officials in New York—have increasingly worked to dictate the national regulation of commerce.

Over the last 20 years, state attorneys general and other state and municipal officials have aggressively filed lawsuits, seeking damages, with the local government entities as plaintiffs. They look to the tobacco litigation model developed in the 1990s by Mississippi trial lawyer Dickie Scruggs—since disbarred and imprisoned on federal corruption charges—in which tobacco companies were sued to defray state health systems’ costs of handling smoking-related ailments. Nowadays, such suits target many industries and affect national policy in areas ranging from pharmaceuticals to guns to financial services.

In one recent example, New York mayor Bill de Blasio announced in January 2018 that he was suing on behalf of the city against five multinational oil companies—BP, Chevron, ConocoPhillips, ExxonMobil, and Royal Dutch Shell—over the most global of policy problems, climate change. Announcing the litigation, the mayor brashly asserted his prerogative to set national policy terms: “We never make the mistake of waiting on our national government to act when it’s unwilling to. This city is acting. We want other cities to act. We want other states to act.”

State officials have used the threat of prosecution to reshape national businesses—most prominently, through New York’s Martin Act, a 1921 state law that gives the Empire State’s attorney general extremely broad powers to investigate, subpoena, sue, and prosecute companies and individuals, even absent any showing of intentional wrongdoing. Former New York attorney general Eliot Spitzer dusted off this old law at the turn of the century and used it to threaten and reshape a host of national industries, including insurance, investment banking, and mutual funds. Among Spitzer’s targets was the insurance giant AIG. In 2004, Spitzer threatened the board of AIG that he would pursue criminal charges against the company unless it ousted its longtime chairman, Maurice “Hank” Greenberg. Facing a bet-the-company legal tussle, the board had to comply. The decision would prove disastrous and sow the seeds of AIG’s near-collapse before the federal government pumped $185 billion into the embattled insurer during the financial crisis.

Among AIG’s many divisions was a “financial-products group,” which traded exotic derivative instruments like credit-default swaps—a way for businesses to hedge against the risk that their customers and suppliers may be unable to pay their bills. Essentially, credit-default swaps are a tradable, and thus highly liquid, form of old-fashioned credit insurance. As tradable contracts, however, they can also afford betting opportunities for speculators, who seek profits from trading such instruments just as they do stocks, bonds, and currencies. AIG’s financial-products group traded in such instruments regularly, which can be a risky business. Greenberg understood these risks: he had launched the financial-products group, and he watched its operations like a hawk. But with Greenberg out the door and new management focused on placating Spitzer and other swarming regulators, company oversight of the financial-products group suffered. Indeed, AIG issued as many credit-default swaps in the seven months following Greenberg’s departure as it had in the prior seven years. In fall 2008, those swap contracts had fallen underwater, and the company teetered on bankruptcy.

Before that bill came due, Spitzer had parlayed his “Sheriff of Wall Street” image into a successful run for governor—though his tenure in that office ended prematurely in a prostitution scandal. Spitzer’s successors followed his example, using the Martin Act’s sweeping powers to seek reforms in several national industries. In fall 2015, then–New York attorney general Eric Schneiderman launched a Martin Act investigation into ExxonMobil—his own foray into the climate-change-policy arena. Like Spitzer, Schneiderman saw his career cut short by a sex scandal. But the law that abetted their regulatory overreach remains in place.

State and local officials are also trying to become backdoor national regulators by throwing their money around—or, more precisely, the money set aside for public workers’ pensions. State and municipal pension systems are, in general, woefully underfunded and squeezing out scarce tax dollars, to citizens’ detriment. (See “Scary Pension Math,” Winter 2016.) These pension systems are also massive investors, holding large corporate-equity stakes. Under rules promulgated by the federal administrative state—in this case, the Securities and Exchange Commission, which controls the proxy-voting process for publicly traded corporations—politicians who oversee state pension funds have used their investments to try to influence corporate behavior to further policy goals related to human rights, health-care reform, gender equity, and the environment.

Thus did Scott Stringer—a nondescript New York politician with no finance background, who spent his adult life as a legislative assistant, state assemblyman, or local elected official—become perhaps the nation’s most influential stock-market investor. As New York City’s comptroller, Stringer oversees five pension funds for city employees, which collectively make up the fourth-largest public-pension plan in the United States and manage more than $180 billion in assets. In late 2014, Stringer announced the launch of what he called the “Boardroom Accountability Project,” designed to influence corporate behavior by leveraging the power of the pension funds’ shares. Stringer’s overt goal: “to ratchet up the pressure on some of the biggest companies in the world to make their boards more diverse . . . and climate-competent.”

Stringer’s activism will probably further his political career, but it is likely to hurt the city pension funds’ investment returns. A 2015 Manhattan Institute study shows a negative relationship between socially oriented shareholder activism and share value. Still, Stringer’s efforts are having an impact. By his own count, some 270 publicly traded U.S. companies have now adopted some variant of his preferred “proxy access” rule. And under pressure from Stringer and other elected officials, some institutional investors—who profit from managing public-pension dollars—have begun pushing their own social agendas.

That a down-ballot city politico like Stringer can have broad national policy impact shows the challenge in reining in the forces of the regulatory state. Yet some reasons for optimism exist. Neomi Rao’s efforts at paring back federal rules will not return our regulatory code to 1960s levels but will certainly do some good, as will the efforts of deregulatory champions leading various authorities, like Pruitt at the Environmental Protection Agency and Hester Peirce on the Securities and Exchange Commission.

The Justice Department has also announced steps to curb the worst abuses of federal regulation by prosecution. Among these is the practice of funneling settlement payments to third parties. The Obama administration had used this tactic to route billions of dollars that businesses targeted by the Justice Department paid to settle their claims to nonprofit entities—money that otherwise would flow to government coffers or to compensate victims. Thus, even as Congress slashed funding for groups like the now-defunct Association of Community Organizations for Reform Now (Acorn), Obama’s executive branch had sent federal dollars their way—an end run around the legislative branch’s constitutional appropriations power. The Justice Department has announced, too, that it would no longer prosecute based on administrative “guidance” that failed to go through the notice-and-comment rule-making prescribed in the Administrative Procedure Act—another method that the Obama administration used to bully businesses, nonprofits, and individuals to do the executive branch’s will, with no judicial review.

The Supreme Court has also taken some positive steps, particularly in the arena of abusive litigation—dating back to the 1990s, when the Court reframed evidentiary rules to weed out the worst “junk science” from federal courtrooms (Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals, 1993). A series of major Court decisions has blocked lower courts from certifying some national class-action lawsuits (Wal-Mart v. Dukes, 2011) and empowered private parties in certain cases to contract out of class-action litigation through alternative dispute resolution (AT&T Mobility v. Concepcion, 2011). Another line of cases has at least somewhat limited the “notice pleading” rules of civil procedure (Bell Atlantic v. Twombly, 2007). More recently, the Court has even begun to limit the worst abuses of forum shopping, putting some jurisdictional limits around International Shoe (Bristol-Myers Squibb Co. v. Superior Court of California, San Francisco County, 2017).

Outside the arena of civil liability, the Court has pushed back when Congress has written criminal laws too vague or ambiguous to put individuals on notice of wrongdoing (Skilling v. U.S., 2010). And there is some hope that the Court may begin to trim back on the deferential Chevron and Auer doctrines that grant so much authority to agency interpretations of laws and regulations. Justices Clarence Thomas and Neil Gorsuch and Chief Justice John Roberts have all signaled willingness to rethink this approach.

But it is a fool’s errand to hope that the Supreme Court will undo the broader excesses of the regulatory state. An expansive reading of federal regulatory power is here to stay. Any hopes that the Court’s 1990s Commerce Clause cases represented more than an outer bound were dashed in Gonzales v. Raich (2005), which reaffirmed the core holding of Wickard v. Filburn. The Supreme Court is not going to revive the nondelegation doctrine. It will neither renounce corporate criminal liability nor vitiate strict-liability crimes. The pre-Erie days of federal common law are gone.

And, of course, every deregulatory effort by the executive branch under President Trump can be reversed by subsequent administrations, just as the Trump administration has begun to undo much of Obama’s regulatory push. Therefore, fundamental reform of the regulatory state rests, as it should, with the legislative branch. Congress has the authority to restrain administrative rule-making—and to instruct courts not to defer to executive-branch readings of statutes and regulations. It has the power to write laws that require showings of intent, to limit federal agencies’ authority to criminalize unknowing violations of malum prohibitum rules, and to alter the balance of power between businesses and prosecutors. It has the ability to limit the reach of state tort law and prosecutions when they interfere with the regulation of interstate commerce. And it has the authority to change shareholder proxy rules that enable state and local pension funds to play politics through the national markets.

The sad reality is that public-choice imperatives have tended to deter Congress from asserting itself in such fashion. As Justice Scalia predicted in his Mistretta dissent, it is easier for legislators to take credit for open-ended laws that leave the executive branch to fill in the details—and assume at least some share of the blame for unintended consequences. Congress has shown greater capacity to block regulatory initiatives than to scale back existing ones—as demonstrated by Republican congressional majorities’ inability to repeal the health-care and financial reforms that were the centerpiece of the prior Democratic leadership. Still, Congress has shown that it can act to move back the regulatory needle, as when it passed legislation cabining the scope of securities and nationwide class-action lawsuits in major 1996 and 2005 reforms (the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act and the Class Action Fairness Act, respectively). And federal legislation has been introduced—and, in many cases, advanced—that would constrain all four forces of the regulatory state.

So there is hope, even if scaling back the regulatory state is a tall task when it requires confronting not only “independent” agencies but also federal prosecutors and private litigators, as well as state and local officials. The first step in this process is understanding the forces that underlie the regulatory behemoth.

Illustrations by Heads of State