On the bench, Clarence Thomas takes precisely the opposite approach from that of Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes, who famously quipped that “the Constitution is what the judges say it is.” Under that rubric, too many justices have imposed their own policy preferences, Thomas says: “You make it up, and then you rationalize it.” According to his own strictly originalist judicial credo, set forth in a 1996 speech, “The Constitution means not what the Court says it does but what the delegates at Philadelphia and at the state ratifying conventions understood it to mean. . . . We as a nation adopted a written Constitution precisely because it has a fixed meaning that does not change. Otherwise we would have adopted the British approach of an unwritten, evolving constitution.” Consequently, “as Justice Brandeis declared in the great case of Erie v. Tompkins, there is no federal general common law. The duty of the federal courts is to interpret and enforce two bodies of positive law: the Constitution and the body of federal statutory law.” What the law schools teach as constitutional law is just a compendium of opinions that might or might not be correct.

In modern times, that’s a radical argument, and not just because it contradicts the idea of a “living Constitution” that evolves to meet changing conditions. It also challenges the doctrine of stare decisis—to respect precedents and let them stand—which, in modern times, has also been a handmaiden of judicial policymaking: judges tinker with the precedents until “they get what they want, and then they start yelling stare decisis, as though that is supposed to stop you,” Thomas said in 2016. True, judges in the lower federal courts pledge to apply precedents faithfully, and many try. But Supreme Court justices, Thomas contends, “are obligated to think things through constantly, to re-examine ourselves, to go back over turf we’ve already plowed, to torment yourself to make sure you’re right.” If they discover that their predecessors were wrong, they are obliged to say so—and even to reverse the Court’s earlier decisions. “I trust the Constitution itself,” Thomas says. “The written document is the ultimate stare decisis.” Very different from Yale Law, he notes, which didn’t assign the Constitution in full.

To see how this works, look at two of Thomas’s opinions bearing on the Constitution’s clause empowering Congress to “regulate commerce with foreign nations, and among the several states, and with the Indian tribes.” In 1995, in United States v. Lopez, the Court struck down a federal law using the Commerce Clause to justify a ban on gun possession in a school zone. Justice Stephen Breyer’s dissent showed the kind of far-fetched, Rube Goldberg reasoning that too often has justified such a law: by hampering education, the forbidden activity would yield a “less-productive citizenry” with “an adverse effect on the Nation’s economic well-being,” he held, so Congress properly forbade it under its Commerce Clause authority.

Chief Justice William Rehnquist’s majority ruling more sensibly declared that the government had exceeded its authority under the Commerce Clause, since it could not show that the forbidden activity “substantially affected” interstate commerce. But Thomas’s opinion, concurring in the judgment but not in its reasoning, warned that even Rehnquist’s criterion, “if taken to its logical extreme, would give Congress a ‘police power’ over all aspects of American life,” from littering to marriage. Indeed, he pointed out, “when asked . . . if there were any limits to the Commerce Clause, the Government was at a loss for words.”

But that’s wrong. Dictionaries from the Founding era clearly define commerce as selling, buying, bartering, and transporting goods. Both The Federalist and the state ratifying conventions used the word to distinguish trade from manufacturing or agriculture, over which the Constitution gives Congress no power. Moreover, if the Framers meant the clause to grant Congress authority over matters that “substantially affect” commerce, why does Article I, Section 8, where the Commerce Clause appears, bother to enumerate such other powers as coining money or punishing counterfeiters or enacting bankruptcy laws—all of which “substantially affect” commerce, as Framers James Madison and Alexander Hamilton pointed out? The Court needs to revisit its Commerce Clause jurisprudence, Thomas concluded, to ensure that it doesn’t make into a reality Madison’s nightmare of a limited government becoming an unlimited one.

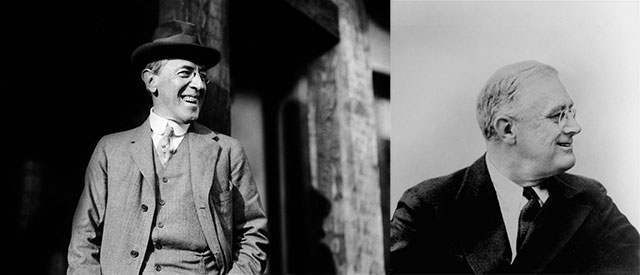

Such misuse of the Commerce Clause to cover the whole web of human activity began in the New Deal, Thomas writes. The “Court’s dramatic departure in the 1930s from a century and a half of precedent” was unequivocally a “wrong turn” that marks the real start of modern illegitimate judicial lawmaking. This was not a wrong turn that the Court made willingly. Up until 1936, it had resolutely resisted Congress’s attempts to use the Commerce Clause as a justification for the flood of New Deal legislation. But after a frustrated Franklin Roosevelt threatened to enlarge the high bench and pack it with his partisans, Justice Owen Roberts, in the infamous switch in time that saved nine, stopped finding New Deal legislation unconstitutional, so that five-to-four decisions against FDR became majority decisions allowing his schemes.

In Wickard v. Filburn, the most fanciful of these decisions, the submissive majority absurdly ruled in 1942 that the Commerce Clause gave the federal government the power to regulate the amount of grain that a farmer could grow to feed to his own livestock, even though agriculture isn’t commerce, and the grain didn’t enter into interstate commerce or, indeed, into any commerce at all. Still, the chastened Court ruled, the grain “substantially affected” the national economy—the first time it had invoked such a criterion—and thus Washington had power over it.

In his dissent in Gonzalez v. Raich in 2005, Thomas denied that the Commerce Clause gave Congress the power to regulate a homegrown agricultural product that never entered into any commerce, implicitly delegitimizing Wickard, which he cited, and thus much of the New Deal and the fast-and-loose jurisprudence that justified it and that continues to rationalize judicial activism to this day. Gonzalez involved two chronically ill Californians who grew and used marijuana to control their pain, thinking themselves protected by California’s legalization of medical marijuana. The Feds thought otherwise, seized six marijuana plants, and charged the invalids with violating the federal Controlled Substances Act. The Court sided with the Feds—over Thomas’s strenuous dissent.

The invalids, he thundered, “use marijuana that has never been bought or sold, that has never crossed state lines, and that has had no demonstrable effect on the national market for marijuana. If Congress can regulate this under the Commerce Clause, then it can regulate virtually anything—and the Federal Government is no longer one of limited and enumerated powers.” Not only does this case not concern commerce; it doesn’t even concern economic activity. “If the majority is to be taken seriously, the Federal Government may now regulate quilting bees, clothes drives, and potluck suppers throughout the 50 States,” he protested. In this same vein, he dissented from the Court’s blessing of Obamacare’s individual mandate in NFIB v. Sebelius in 2012, rejecting “the Government’s unprecedented claim in this suit that it may regulate not only economic activity but also inactivity that substantially affects interstate commerce.”

“The Commerce Clause was the New Deal’s bluntest weapon for subverting the Founders’ Constitution.”

The Commerce Clause was the New Deal’s bluntest weapon for subverting the Founders’ Constitution and extending the imperium of what we now call the Administrative State. But after considering how FDR & Co. had done it, Thomas came to see that the subversion was more complicated. The New Deal Congress wielded its enlarged authority not directly but through executive-branch agencies such as the Agricultural Adjustment Administration, the National Labor Relations Board, and the Securities and Exchange Commission. In several 2015 opinions, Thomas focused on how these agencies increasingly undermine the original Constitution even more insidiously than Congress’s torturing of the Commerce Clause. These opinions are all concurrences or dissents, not the Court’s majority ruling. Their importance lies in making what previously had been an academic and journalistic concern part of official Supreme Court jurisprudence and targeting previous rulings for future reversal.

“We have overseen and sanctioned the growth of an administrative system that concentrates the power to make laws and the power to enforce them in the hands of a vast and unaccountable administrative apparatus that finds no comfortable home in our constitutional structure,” Thomas lamented in his concurrence in Department of Transportation v. Association of American Railroads. “The end result may be trains that run on time (although I doubt it), but the cost is to our Constitution and the individual liberty it protects.” Since the High Court remanded the complex railroad-rate-setting case back to the lower courts, he set out some principles for the guidance of those courts and the consideration of his colleagues in future cases.

The combination in the same hands of the power to make the laws and the power to carry them out is the essence of arbitrary rule by decree, the Founders believed, guided by such writers as the Baron de Montesquieu, John Locke, and William Blackstone. For them, the separation of powers was key to the protection of liberty from tyranny, he writes. The Constitution vested all legislative power in Congress, all executive power in the president, and all judicial power in the Supreme Court and inferior courts, because the Framers did not want to have those powers delegated to other hands, lest it bring about the “gradual concentration of the several powers in the same department,” as Madison put it in Federalist 51. As Locke himself had said, Thomas reminds his colleagues, “The legislative cannot transfer the power of making laws to any other hands: for it being but a delegated power from the people, they who have it cannot pass it over to others.”

Sure enough, the delegation of legislative powers to the administrative agencies, whose rules bind citizens and thus are laws in all but name, results in just such a dangerous concentration, which the Court permitted by gradual and almost careless application of an “intelligible purpose” test. Originally, the test concerned the very narrow case of a tariff law that left it to the president to determine if the conditions that the law had set for rate changes had been met, a factual determination that, as a later decision pointed out, did not concern questions of justice or expediency—policy questions that demand a legislative determination. But, Thomas observed, the Court forgot this narrow qualification and, in time, allowed Congress to delegate its lawmaking power to agencies without reservation.

Perhaps we deliberately departed from the separation [of powers], bowing to the exigencies of modern Government that were so often cited in cases upholding challenged delegations of rulemaking authority,” Thomas muses. Perhaps, as an earlier Court conceded, “our jurisprudence has been driven by a practical understanding that in our increasingly complex society, replete with ever changing and more technical problems, Congress simply cannot do its job absent an ability to delegate power under broad general directives.”

That happened, of course, not by accident but because Woodrow Wilson and his fellow Progressives rejected the Founders’ Constitution as a cumbrous, outworn relic, whose separated powers and checks and balances clogged the government efficiency that a fast-changing world needs, they claimed. Modernity requires rule not by the democratically elected representatives of an ill-schooled citizenry but by highly trained, public-spirited experts who embody Hegel’s spirit of History and know which way its arc bends. After Wilson had laid the intellectual foundation, FDR later enlarged the Administrative State by an order of magnitude, on the principle, he said, that “new conditions impose new requirements upon government and those who conduct government.” Suited to this challenge, executive-branch agencies would emit a torrent of rules with the force of law like a legislature, carry them out and enforce them like an executive, and adjudicate and punish infractions of them like a judiciary, depriving citizens of their property without due process of law.

However practical that delegation might seem, it is unconstitutional six ways from Sunday. “To understand the ‘intelligible principle’ test as permitting Congress to delegate policy judgment in this context is to divorce that test from its history,” Thomas objects. “We should return to the original meaning of the Constitution: The Government may create generally applicable rules of private conduct only through the proper exercise of legislative power. I accept that this would inhibit the Government from acting with the speed and efficiency Congress has sometimes found desirable.” But that’s a virtue of constitutional lawmaking, not a flaw. As Hamilton put it in Federalist 73: “The injury which may possibly be done by defeating a few good laws will be amply compensated by the advantage of preventing a number of bad ones.”

If the delegation of legislative power to executive agencies is illegitimate, the delegation of judicial power is a special affront to judges like Thomas. That power isn’t Congress’s to begin with, so how can it delegate what it doesn’t have? Yet bizarrely, the Supreme Court itself, in a wartime price-control case, Bowles v. Seminole Rock & Sand, “requires judges to defer to agency interpretations of regulations, . . . giving legal effect to the interpretations rather than the regulations themselves,” Thomas complained in Perez v. Mortgage Bankers Association in 2015. That doctrine of deference, Thomas objects, has now taken on a life of its own, so that judges defer not only to agency interpretations of their own regulations but of other agencies’ regulations and even of criminal sentencing—and even when an interpretation differs from a previous interpretation of the same regulation, so that it amounts to new lawmaking utterly confusing to the citizens the regulation binds.

For the Founders, separation of powers wasn’t protection enough against tyranny. They also designed a system of checks and balances to prevent an improper accumulation of power in any one branch. The judiciary plays a critical role in this dynamic equipoise, and failure to exercise its independent judgment of what is lawful for executive-branch agency actions amounts to a gross dereliction of duty, Thomas charges. After all, the Founders specifically protected judicial independence with lifetime tenure and irreducible salaries, insulations against the pressure of public opinion that they purposely withheld from the other two branches, subject to the discipline of regular elections. “You don’t review cases when you say, ‘Oh, we defer to virtually everything the agency does,’ ” Thomas said last year. “We don’t do that to district judges, and district judges are Article III judges.” The Supreme Court should give agency interpretations a tighter, not a looser, scrutiny than it gives district or appeals court decisions—especially since agency bureaucrats have tenure almost as secure and unaccountable as judges enjoy.

“Probably the most oft-recited justification for Seminole Rock deference is that of agency expertise in administering technical statutory schemes,” Thomas writes. But that defense “misidentifies the relevant inquiry. The proper question faced by courts in interpreting a regulation is not what the best policy choice might be, but what the regulation means.” And who better than a judge to analyze the meaning of the language of a law or regulation?

Finally, in Michigan v. EPA, Thomas concluded that what goes for Seminole Rock deference goes equally for the deference doctrine pronounced in Chevron v. Natural Resources Defense Council in 1984. That Chevron doctrine assumes that “Congress, when it left ambiguity in a statute meant for implementation by an agency, understood that the ambiguity would be resolved, first and foremost, by the agency, and desired the agency (rather than the courts) to possess whatever degree of discretion the ambiguity allows.” Nevertheless, when an agency interprets a regulation, Thomas writes, its sub rosa lawmaking cries out for judicial review. Deference thus forces judges “to abandon what they believe is ‘the best reading of an ambiguous statute’ in favor of an agency’s construction. It thus wrests from Courts the ultimate interpretative authority to ‘say what the law is’ ”—precisely the authority that Chief Justice Marshall claimed for the judiciary in Marbury v. Madison. That can hardly be constitutional.

Thomas’s magnum opus so far, his concurrence in McDonald v. Chicago, a 2010 gun-rights case in which the Court upheld Chicago residents’ right to bear arms, is a textbook demonstration of his method of judging. Here, with his characteristic skepticism toward stare decisis, he utterly repudiates the Supreme Court’s two most tragically wrong and history-changing decisions—the Slaughter-House Cases (1873) and United States v. Cruikshank (1876), the cases that strangled Reconstruction in its cradle and licensed the generations-long grip of Jim Crow on black Southerners. He shows that the Court in those cases misinterpreted both how the framers of the Fourteenth Amendment understood the language in which they couched it, and how contemporary commentators heard that language. He demonstrates that that original understanding belongs to an unbroken intellectual tradition that derived from Magna Carta and the English Bill of Rights. It was asserted in the American colonies at least as early as 1636, was affirmed in the Declaration of Independence, and was powerfully restated by Lincoln as an antislavery rationale. And vibrating throughout Thomas’s McDonald opinion is a note of pained indignation that his own Court in earlier days could have participated in overturning the equality of rights that so many had given their lives to uphold.

“When an agency interprets a regulation, Thomas writes, its sub rosa lawmaking cries out for judicial review.”

The American Founders well knew, Thomas writes, that slavery was “irreconcilable with the principles of equality, government by consent, and inalienable rights proclaimed by the Declaration of Independence and embedded in our constitutional structure.” To resolve that contradiction, the nation fought a bloody Civil War, on “the leading principle—the sheet anchor of American republicanism,” in Lincoln’s phrase, that “no man is good enough to govern another man, without that other’s consent.” After the war, the Fourteenth Amendment sought to heal the wound that slavery had left behind. The amendment began by unambiguously declaring—contrary to the Supreme Court’s 1857 holding in Dred Scott—that black Americans were citizens of the United States and of the state wherein they resided. Full citizens, the amendment went on to say: for it commanded that “[n]o State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States.”

Heartbreakingly, Slaughter-House and Cruik- shank neutered that provision almost before the ink had dried on it. In McDonald, showing reverence for stare decisis, Thomas’s fellow justices employed a work-around for the privileges-and-immunities issue. The right to keep arms is fundamental to our nation’s particular scheme of ordered liberty and system of justice, the Court ruled, and therefore, through the doctrine of “substantive due process”—which holds that some rights are so basic that they can’t be withdrawn without due process of law—the Second and Fourteenth Amendments prohibit Chicago from banning residents from keeping handguns in their homes.

But Thomas always cares that the Court should not only reach the right conclusion but should also get there through correct legal reasoning, faithful to the original text. He makes short work of the “substantive due process” notion. It is, as anyone knows who has tried to remember what it means for more than ten minutes, a will o’ the wisp, mere smoke and mirrors, more fictional than most legal fictions. “Moreover, this fiction is a particularly dangerous one,” Thomas writes, since the Court has found no authoritative basis for distinguishing “ ‘fundamental’ rights that warrant protection from nonfundamental rights that do not,” allowing judges excessive “flexibility” in interpretation, which has led them to invent rather than to interpret law. Indeed, a mountain of erroneous judgments rests on this doctrine, so while junking it would play havoc with stare decisis, that’s a better path than piling error upon error.

Far better to put aside stare decisis and substantive due process in this case and straightforwardly apply the Fourteenth Amendment’s privileges and immunities clause, since the English-speaking peoples, from the time they began to speak about law, have understood that “privileges and immunities” means exactly those basic rights and freedoms that the doctrine of substantive due process pussyfoots around. The 1765 Massachusetts Resolves, for instance, equate the rights that “are founded in the Law of God and Nature, and are the common Rights of Mankind” with the “essential Rights, Liberties, Privileges and Immunities of the people of Great Britain” and of Britain’s American colonies. Treaties ceding the Louisiana and Florida territories to the United States in 1803 and 1819 reflexively assured the new inhabitants that they would be admitted, “according to the principles of the federal Constitution, to the enjoyments of all the privileges, rights, and immunities, of the citizens of the United States.”

In the years just after the Civil War, the formula similarly meant the full panoply of constitutional rights, as witness President Andrew Johnson’s proclamation of amnesty to Confederates, which restored “all rights, privileges, and immunities under the Constitution.” The framers of the Fourteenth Amendment meant no less. Representative John Bingham, its chief draughtsman, declared that the amendment would “secur[e] to all the citizens in every State all the privileges and immunities of citizens,” and it would “arm the Congress of the United States, by the consent of the people . . . , with the power to enforce the bill of rights as it stands in the Constitution today.” Further, said Senator Jacob Howard during the debates on the amendment, its aim was prohibiting the states “from abridging the privileges and immunities of the citizens of the United States,” including “the personal rights guaranteed and secured by the first eight amendments of the Constitution.” That was how contemporaries understood the amendment: a typical commentator wrote in 1868 that the rights guaranteed by Article IV of the Constitution and the Bill of Rights, “which had been construed to apply only to the national government, are thus imposed upon the States.” (Thomas never investigates the intentions of the Framers, thus avoiding, in this case, the complication of the Fourteenth Amendment Congress’s funding of the District of Columbia’s segregated public schools.)

The reason that there is any question about whether the Fourteenth Amendment applies the Bill of Rights to the states is that, in the aftermath of the Civil War, Southern whites did not want blacks to arm themselves. And they prevailed. So while it’s true that the Court’s precedents deny that the Fourteenth Amendment bans states from abridging the rights that the first eight amendments protect, particularly the right to bear arms, those precedents are as unsavory as they are incoherent, and they should have been overruled long ago.

Slaughter-House, decided just eight years after the Confederacy’s defeat and five years after the Fourteenth Amendment’s ratification, amalgamated several lawsuits challenging a Louisiana law that required New Orleans butchers to relocate to a single market where animals could be unloaded from trains and slaughtered, to keep the mess and stench in one spot, as many northern cities had already done. The butchers claimed that, by interfering with their right to earn a living—which was not true—the state was abridging their Fourteenth Amendment privileges and immunities as U.S. citizens. The Court, not lingering over the fact that the right the butchers claimed was not one protected by the Bill of Rights and well aware that the war-scarred nation was watching closely, ruled that the rights protected by the federal and state governments were not identical, and that the Fourteenth Amendment protected only federal rights, such as using the nation’s seaports and enjoying its protection on the high seas. The Bill of Rights? No.

Cruikshank was the Court’s shameful response to the 1873 Colfax Massacre, “the bloodiest single instance of racial carnage in the Reconstruction era,” historian Eric Foner writes. To protect their victory in a ferociously contested 1872 election, a black Republican militia occupied Louisiana’s Grant Parish courthouse, only to be overwhelmed by ex-Confederate soldiers, the Ku Klux Klan, and the White League, who left up to 165 blacks dead in mass graves, many shot in the back of the head.

Mindful that no Louisiana jury would convict whites of murdering blacks, lawyers for the dead filed a federal lawsuit under one of the three 1870–71 Enforcement Acts aimed at putting teeth in the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments’ protection of freedmen’s rights—in this case, by criminalizing conspiracy to injure or intimidate citizens with intent to prevent their free exercise of any right or privilege granted by the Constitution. But the right to assemble and to bear arms, which the indictment claims the nine defendants infringed, are not rights “granted” by the Constitution, the chief justice wrote for the Supreme Court. These rights preexisted the Constitution, and the First and Second Amendments merely command Congress not to infringe them. As for the Enforcement Acts, the Court wrongly claimed, they apply only to actions by states, not individuals. To add insult to injury, the state of Louisiana erected a historical marker in 1951 commemorating the “Colfax Riot.”

“Cruikshank,” Thomas acerbically and unarguably concludes, “is not a precedent entitled to any respect,” the more so because of its consequences. Without federal enforcement of the freedmen’s inalienable right to keep and bear arms, the armed thugs of the Ku Klux Klan, the Knights of the White Camellia, and their ilk could “subjugate the newly freed slaves and their descendants through a wave of private violence designed to drive blacks from the voting booth and force them into peonage, an effective return to slavery.” Typical was Pitchfork Ben Tillman’s cold-blooded massacre in South Carolina of “a troop of black militiamen for no other reason than that they had dared to conduct a celebratory Fourth of July parade through their mostly black town.” Imagine: they celebrated the Declaration of Independence! But for decades, groups like Tillman’s “raped, murdered, lynched, and robbed as a means of intimidating, and instilling pervasive fear in, those whom they despised,” Thomas writes. “Between 1882 and 1968, there were at least 3,446 reported lynchings of blacks in the South.”

Only firearms could protect those blacks, and only sometimes. “One man recalled the night during his childhood when his father stood armed at a jail until morning to ward off lynchers,” Thomas writes. The experience left the man “with a sense, not ‘of powerlessness,’ but of the ‘possibilities of salvation’ that came from standing up to intimidation.” Thomas’s grandfather, who worked so hard to instill the old American virtues of self-reliance and personal responsibility in him, would heartily approve.

Finally, glance briefly at three related opinions that form a single argument validating Juan Williams’s recent claim “that Clarence Thomas is now leading the national debate on race.” In his concurrence in Adarand v. Pena, a 1995 case involving preferences for government subcontractors employing black and Hispanic workers, Thomas wrote that there’s no moral or constitutional difference “between laws designed to subjugate a race and those that distribute benefits on the basis of race in order to foster some current notion of equality. Government cannot make us equal; it can only recognize, respect, and protect us as equal before the law.” Discrimination, whether maliciously or benignly intended, subverts the core American principle that all men are created equal. Insidiously, “positive” discrimination “teaches many that because of chronic and apparently immutable handicaps, minorities cannot compete with them without their patronizing indulgence.” How can such discrimination fail to engender hurtful feelings of superiority or resentment in the majority and dependence and a sense of entitlement among minorities?

“Discrimination, however intended, subverts the core American principle that all men are created equal.”

Thomas’s masterful concurrence in Missouri v. Jenkins, another 1995 case, which ended federal district judge Russell Clark’s years-long, Ahab-like quest to impose his megalomaniacal version of racial justice on the Kansas City, Missouri, schools, skewered seven pernicious errors in 40 years of federal race jurisprudence. First, Thomas noted that racial isolation may result not from intentional state-sponsored segregation but from “voluntary housing choices or other private decisions” that don’t concern the courts. Racial imbalances are not, in themselves, unconstitutional. Second, even if you make the hard-to-prove assumption that racial imbalance is a “vestige” of past state segregation, what remedy can the courts provide to behavior that stopped 30 years ago? Third, and particularly nasty, is the assumption that “anything that is predominantly black must be inferior” and its corollary, that “segregation injures blacks because blacks, when left on their own, cannot achieve.” Such racist stereotypes have no place in American jurisprudence.

Fourth, the Court’s landmark 1954 school desegregation decision, Brown v. Board of Education, introduced an unnecessary confusion into race jurisprudence—one that would later ensnare Judge Clark. Brown, Thomas writes, “did not need to rely upon any psychological or social science research in order to announce the simple, yet fundamental truth that the Government cannot discriminate among its citizens on the basis of race.” However, as Thomas is too polite to say here, it did. It accepted a tissue of social-scientific hocus-pocus involving “experiments” with black and white dolls, purporting to prove that segregation generates feelings of inferiority in black students that impairs their ability to learn. But that’s neither here nor there, Thomas contends. “Segregation was not unconstitutional because it might have caused psychological feelings of inferiority,” he writes, but “because the State classified students based on their race.”

He spoke more plainly in a 1987 article: “Brown was a missed opportunity, as [are] all its progeny, whether they involve busing, affirmative action, or redistricting,” he declared. The Court should have focused on reason, justice, and freedom, not sentiment, sensitivity, and dependence. A Court that wanted to “validate the Brown decision” would replace Chief Justice Earl Warren’s decision with one more in keeping with the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence. Thomas’s candidate would be Justice John Marshall Harlan’s ringing 1896 dissent in Plessy v. Ferguson (a case that the Brown Court, respecting stare decisis, failed to overrule): “Our Constitution is color-blind and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens. . . . The law regards man as man and takes no account of his surroundings or of his color when his civil rights as guaranteed by the supreme law of the land are involved.”

Fifth, even compared with busing or affirmative action, Judge Clark’s remedy—a megaproject of social engineering aimed at transforming the Kansas City schools into magnet schools by outfitting them with Olympic swimming pools, broadcast studios, model UN chambers wired for simultaneous translation, planetariums, even a 25-acre farm—dizzyingly exceeded the judiciary’s constitutional powers to interpret the law. It was a bad enough assault upon federalism for Judge Clark to order the Kansas City school district to pay a quarter of the cost of all this. But to order the district to raise property taxes in order to pony up, and to enjoin the state from interfering, as an earlier Supreme Court ruling did—that flings down federalism and dances upon it. Sixth, as this case shows, the Founders were right to view with cold-eyed suspicion equity courts, with their power to impose “equitable remedies.” As Thomas Jefferson put it: “Relieve the judges from the rigour of text law, and permit them, with pretorian discretion, to wander into it’s equity, and the whole legal system becomes incertain.”

Seventh, even if Judge Clark were right that past segregation “caused a system-wide reduction in student achievement,” and even if his pharaonic program produces benefits—though it didn’t boost student performance—it produces them for individuals who were not victims of discrimination. “A school district cannot be discriminated against on the basis of its race, because a school district has no race,” Thomas observes. “It goes without saying that only individuals can suffer from discrimination, and only individuals can receive the remedy.”

A note of cold scorn runs through Thomas’s 2003 opinion in Grutter v. Bollinger, the third key race case, concerning affirmative-action admissions to the University of Michigan Law School. He is striving for jocularity, but he seems to have run out of patience with the self-cherishing antics of overpaid functionaries like President Lee Bollinger and his fellow administrators, glowing with the virtue of their good intentions and careless of the havoc they wreak. Here they have an institution financed by the taxpayers of their state, though only 27 percent of admitted students are Michiganders and only 16 percent of graduates stay in the state. So for starters, there’s no compelling state interest in having this school exist.

And there’s less compelling state interest for it to admit ill-prepared minority students to achieve “diversity,” which offers no educational benefit, despite the law school’s claim, but is merely an aesthetic preference of Bollinger et al., who want to see a smattering of minority faces in their lecture halls. Too bad that the Court’s majority fell for “a faddish slogan of the cognoscenti,” though at least it tacked on a 25-year sunset clause to its approval of the law school’s brand of affirmative action. Despite precedents holding “that racial classifications are per se harmful and that almost no amount of benefit in the eye of the beholder can justify such classifications,” the majority decision still clings to “the benighted notions that one can tell when racial discrimination benefits (rather than hurts) minority groups, and that racial discrimination is necessary to remedy general societal ills.”

Much has been said about the supposed (but illusory) educational benefits to white students of a racially diverse class, and we know what aesthetic and narcissistic pleasure it gives the administration, but what about affirmative action’s supposed minority beneficiaries? “The Law School tantalizes unprepared students with the promise of a University of Michigan degree and all of the opportunities that it offers,” Thomas writes. “These overmatched students take the bait, only to find that they cannot succeed in the cauldron of competition.” And what about the “handful of blacks who would be admitted in the absence of racial discrimination”—like Thomas at Yale Law? “The majority of blacks are admitted to the Law School because of discrimination, and because of this policy all are tarred as undeserving.” Moreover, the taint follows the deserving no matter how high they ascend and how much they achieve, Thomas says, as he well knows.

Instead of their constant “social experiments on other people’s children,” Thomas writes, why don’t the nation’s elites honor the heartfelt and prophetic plea of Frederick Douglass a century and a half ago? “What I ask for the negro is not benevolence, not pity, not sympathy, but simply justice. The American people have always been anxious to know what they shall do with us. . . . Do nothing with us! Your doing with us has already played the mischief with us,” Douglass implores in the passage with which Thomas opens his Grutter opinion. “[I]f the negro cannot stand on his own legs, let him fall also. All I ask is, give him a chance to stand on his own legs!” That’s one heroically self-reliant man quoting another such. The country would do well to heed their hard-won advice. We fought a Civil War; we had a civil rights movement: now black Americans—and only black Americans—can work their own liberation, after half a century of social engineering that harmed both the country and its black citizens.

The Framers had hopes, but no illusions, that the Constitution would be eternal. It was just a parchment barrier, they said, guarding against the ambition of the power-mad or the periodic folly of a democratic majority. To animate and preserve it, they thought, would take a culture of liberty—a belief in the values that sustain freedom throughout the whole people, “those basic principles and rules without which a society based upon freedom and liberty cannot function,” as Thomas puts it. And much as Madison believed in the self-regulating constitutional mechanism that he had designed, in which ambition would counteract ambition, even he conceded that the whole contraption couldn’t work without at least a smattering of virtue, even a few thoroughly public-spirited individuals, somewhere in the system.

In our age of enraged shrinking violets, in which hypersensitivity to imagined slights alternates with blind rage against any nonconformity to orthodoxy, Clarence Thomas is one of a handful of honest and brave iconoclasts who love liberty, especially the freedom to think for oneself, and know how America, imperfect as all human things are imperfect, nevertheless was uniquely conceived in liberty and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal. We marvel that late-eighteenth-century America produced its band of great men who invented our republic on such revolutionary principles. It’s a marvel that there are some who’d like to restore it as the world’s beacon of individual liberty. Through a similarly lucky alchemy of character and culture that nurtured the Founders, our age has produced Justice Thomas. It remains to be seen if it has produced enough of his ilk to kindle a new birth of freedom.

Read Part I of “The Founders’ Grandson” here.

Top Photo: The Supreme Court in 2017, with Justice Thomas seated second from right (DPA PICTURE ALLIANCE/ALAMY STOCK PHOTO)