In 1943 and 1944, a New York theatergoer in the mood for a musical was most likely interested in new sensations such as One Touch of Venus, Carmen Jones—the black-cast version of Carmen, with English lyrics—or, especially, an unexpected smash called Oklahoma! If tickets to these shows proved elusive, one could drop in on another solid hit running at the time. Like most musicals back then, it was about white people, but a black man had written the score—the first time this had happened on Broadway, though no one seemed to notice, and there have been only two such cases since, both flops. This one, however, enjoyed a healthy and profitable one-year run. It then toured the country.

Its composer was none other than Fats Waller, the great jazz pianist. The man now iconic as a roly-poly jokester tickling the ivories wrote not a revue collection of songs performed by black actors but a standard-issue “book” show, centered on white performers. Early to Bed, then, was history, or should have been, but it has instead been relegated to a footnote in the story of musical theater. Even aficionados have typically never heard of it. Waller’s Wikipedia entry doesn’t mention the show; neither does Thomas Hischak’s The Oxford Companion to the American Musical.

Early to Bed’s high-quality melodies have been underacknowledged, to say the least. Moreover, the show marked the beginning of what would almost certainly have been a new direction in Waller’s creative output—toward musical theater, a development that in turn likely would have altered the history of Broadway, especially for blacks. Alas, Waller died early in the show’s run, and this history went unwritten, illustrating again the role that chance plays in events. Had Waller begun a string of tuneful Broadway successes—and all evidence suggests that he would have done so—he could have inspired and paved the way for other blacks to create musical-theater works for mainstream consumption. Broadway could have seen a re-blossoming of the “Black Broadway” flowerings that had occurred in the decades before World War II, when Will Marion Cook, Bob Cole, the Johnson brothers, Eubie Blake, Noble Sissle, and many others enjoyed success. Black composers could have influenced the trajectory of Broadway music, as Hamilton’s rap and R&B are doing today.

Though it’s natural to wonder about the role of racism here, Early to Bed’s obscurity owes principally to other factors. Chronicles of musical-theater history, like those of any art form, focus on what pushed the form forward, not the state-of-the-art also-rans. Broadway musicals were at the time produced almost as prolifically as movies; for every Show Boat, two or three bread-and-butter shows came and went, unremembered. That Early to Bed was one of these is a judgment that no one would consider unfair. Even the fanatic can draw a blank on the titles of unambitious productions of Early to Bed’s era, such as Beat the Band the year before or Follow the Girls the year after.

Further, the tradition of recording original-cast albums became standard practice only in the year that Early to Bed opened, and then only for the longest-running or most prestigious productions. This meant that in 1943, even a solid hit like Something for the Boys, with a Cole Porter score and starring Ethel Merman, was not recorded as an album. Scores survive for some of the unrecorded shows of the time; unfortunately, Early to Bed is not one of them. Sheet music for six of its 13 songs was published, but a few dozen bars of piano music are a pale reflection of how a song was performed on stage with an orchestra, elaborate musical arrangement, and choreography. The rest of the score exists only in fragments.

Yet these fragments reveal that Early to Bed was as musically delightful as we would expect material written by Waller at the height of his creative powers to be. The show represents a forgotten chapter in Waller’s life and creative output. It deserves to be revived by professionals devoted to making old musicals sing again.

Fans and jazz historians cherish Fats Waller most for his titanic ability at stride piano—an elaboration on ragtime, with hand-stretching intervals in the left hand that allowed the thumb to contribute a countermelody rather than just doubling the octave, while the right hand not only played the melody but also gamboled through twinkling runs and arpeggios. The living-room pianist who can manage a decent rendition of “The Entertainer” typically finds transcriptions of stride-piano songs like Waller’s “Handful of Keys” less approachable, yet Waller took to the form as if born to it. As a teen in Harlem in the 1910s, Waller learned James P. Johnson’s stride hit “Carolina Shout” from the piano roll by slowing down the mechanism and following the fingering on the keyboard. Despite the admonitions of his preacher father, Waller was soon playing professionally, eventually with various incarnations of a small traveling band. His electricity stood out, as did that of Louis Armstrong, who came to prominence at the same time. In the middle of bandleader Fletcher Henderson’s “The Henderson Stomp” in 1926, a piano solo rips in that, even amid the dim old sonics, grabs the listener’s ear with its strong rhythm and crystal-clear melodic articulation. It was Waller, working as a temporary pianist in just one gig of many.

Waller’s career was devoted primarily to performing as a singer-pianist while composing and selling individual songs, for which he is best known today, especially “Ain’t Misbehavin’” and “Honeysuckle Rose.” But he did make occasional forays into musical theater, and in his annus mirabilis of 1929, he placed a show and a half on the Great White Way: Hot Chocolates, a revue that introduced “Ain’t Misbehavin’,” moved downtown, while he shared composing chores with his pianist and composer mentor James P. Johnson for Keep Shufflin’, a sequel to the legendary Shuffle Along.

However, even as late as 1943, the idea of a black composer writing the score for a standard-issue white show was unheard of. When Broadway performer and producer Richard Kollmar began planning Early to Bed, his original idea was for Waller to perform in it as a comic character, not to write the music. Waller was, after all, as much a comedian as a musician. Comedy rarely dates well, but almost 80 years later, his comments and timing during “Your Feet’s Too Big” are as funny as anything on Comedy Central, and he nearly walks away with the movie Stormy Weather with just one musical scene and a bit of mugging later on, despite the competition of Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, Lena Horne, and the Nicholas Brothers.

Kollmar’s original choice for composer was Ferde Grofé, best known as the orchestrator of George Gershwin’s “Rhapsody in Blue,” whose signature compositions were portentous concert suites. But Grofé withdrew, and it is to Kollmar’s credit that he realized that he had a top-rate pop-song composer available in Waller. Waller’s double duty as composer and performer was short-lived. During a cash crisis and in an advanced state of intoxication, Waller threatened to leave the production unless Kollmar bought the rights to his Early to Bed music for $1,000. (This was typical of Waller, who often sold melodies for quick cash when in his cups. The evidence suggests, for example, that the standards “I Can’t Give You Anything but Love” and “On the Sunny Side of the Street” were Waller tunes.) Waller came to his senses the next day, but Kollmar decided that his drinking habits made him too risky a proposition for eight performances a week. From then on, Waller was the show’s composer only, with lyrics by George Marion, whose best-remembered work today is the script for the Astaire-Rogers film The Gay Divorcée.

With personnel matters resolved, Early to Bed had an easy birth. George Marion’s daughter Georgette told me how, during the months before the premiere, Waller often visited the Marions’ apartment to work with her father. At the premiere of the Boston tryout, Waller was so nervous about how the songs would be received that he fortified himself with Old Grand-Dad before settling in with the audience for the second act. He needn’t have worried: the reviews were good, and the show sailed into New York on June 17, 1943, becoming an instant success and running for 380 performances.

From a modern perspective, the plot of Early to Bed is more generously viewed as an extended sketch than as a story. After Oklahoma!, even light musical-comedy plots were expected to show a basic coherence and relatively sophisticated integration of music with narrative. Early to Bed was created just before that revolution in standards, and its script was more like what mid-twentieth-century television variety shows would do with their skits.

In brief: an aging bullfighter’s car breaks down in Martinique, where he, with his son and his black valet (the role that Waller was to have played), has traveled in hopes of making a comeback at the Pan-American Goodwill Games. The son gets hit by a car and is taken to convalesce at the Angry Pigeon brothel, run by Rowena, a former schoolteacher. The woman driving the car, a nightclub dancer on her way to a gig, convalesces alongside him, and the two fall in love. Meanwhile, the bullfighter, “El Magnifico,” and Rowena turn out to have had a fling in the past and consider rekindling it. With the exception of Eileen, a newly hired prostitute, all the newcomers—including the California State University track team, coming through for the games—assume (despite what one would regard as rather obvious signs to the contrary) that the Angry Pigeon is a finishing school.

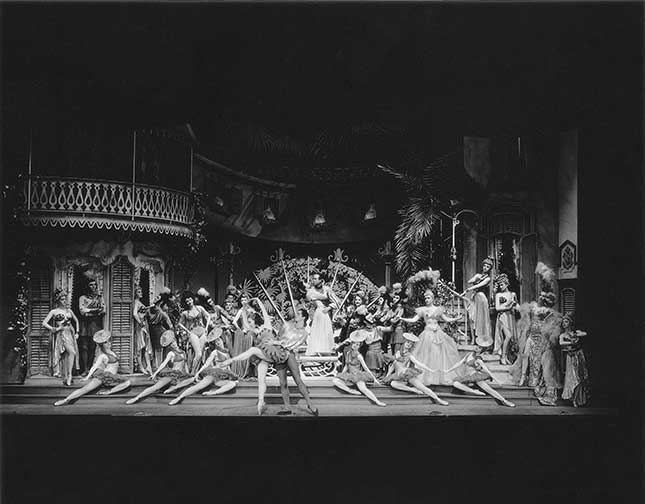

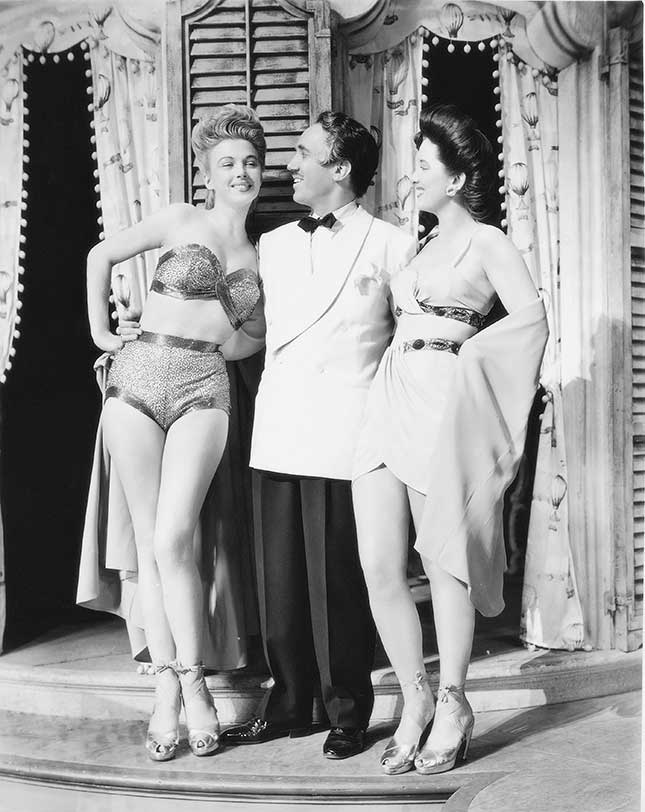

Early to Bed’s cast members were dependables of the era. None are resonant names today, with the possible exception of Jane Kean, who played Eileen; she became best known for playing Trixie in Jackie Gleason’s Honeymooners franchise after the famous 39 filmed half-hour episodes, when she replaced Joyce Randolph. It was not star power but sex that kept audiences interested in such a “plot”: the show was dubbed “An Oversexed Musical” by the Chicago Daily News during its tour, and young Maurice Waller’s mother (Waller’s second wife) deemed the show too bawdy for him to see. In the second act, the girls’ float costumes were announced with lubricious labels like “Inter-American Naval Accord,” “The Liberated Areas,” “The Spirit of Global Uplift,” and “All Out for Hemisphere Defense.” The costumes were “brilliant and sparse,” according to Burns Mantle at the Daily News, while the female chorus included four top models. Early to Bed was a feast for the eyes: even the sets won applause, the way they did at the 2016 She Loves Me revival.

It is the score, however, that makes Early to Bed worth remembering. Only two of its songs have been commonly heard since 1944—“When the Nylons Bloom Again” and “The Ladies Who Sing with the Band,” which were published as sheet music and thus available to be taken up for the 1978 Waller revue Ain’t Misbehavin’, a smash endlessly revived since. However, the silky love duet “Slightly Less than Wonderful” and the ballads “This Is So Nice” and “There’s a Man in My Life” are all top-rate, outshining in musical and lyrical craft equivalent numbers in typical musicals of their time, including by star composers such as Richard Rodgers and Cole Porter. Two other songs are known only to obsessive collectors: “Hi-De-Ho High,” about a mythical Harlem high school, is irresistibly hot; while “Martinique” is a maddeningly infectious tune that Waller recorded only as an instrumental, whose clever lyric in the script (with two and a half refrains) about the pliant mood the island puts one in (“They keep a mine-sweeper near / Just to sweep up discarded brassieres here / If you’re inclined to undress / There’s yes in the air in Martinique”) would surely be better known if the show had been recorded. Beyond that, two other fine songs exist in handwritten manuscripts but were never published as sheet music: the title song, with a warm, pleasing melody and naughtily clever lyrics; and the lush ballad “Long Time, No Song.”

Sadly, while Waller’s entire recorded output is now available beautifully preserved on CDs and mp3s, four of the songs he wrote for the biggest stage hit of his life are lost to the ages—not published as sheet music, preserved as preprint manuscripts, or recorded in any form. Only their lyrics survive, in the final script—and even there, only partially. After Early to Bed closed in 1944, the conductor’s score and orchestra parts were also lost. Before the institutionalization of musical theater as an art, the form was considered topical and evanescent, with some justification. No one in 1943 thought that people even a year later—let alone 70 years later—might want to hear the songs from Early to Bed, much less in their original arrangements.

In 2009, the staff of Musicals Tonight, a musical-theater company in New York, crafted a small-scale revival of the show. To re-create the lost songs, they located Harold “Stumpy” Cromer, a dancer from the original production, and asked him to recall these songs as best he could. This was precious archaeology, but 65 years inevitably filters recollection to the point that Cromer’s recollections of the songs—like Gershwin collaborator Kay Swift’s of some of his lost material, 50-plus years removed—are more approximations than reproductions. Cromer has since died, as has veteran tapper Jeni LeGon, who played the love interest of the black valet character, and Jane Kean—and with them, living memory of these songs’ actual melodies and full lyrics.

One song, however, is partially recoverable. Though Waller left little by way of a paper trail, a box of his working papers for Early to Bed survives and is held in Teaneck, New Jersey, by the son of the lawyer whom Waller’s son Maurice employed. He was kind enough to lend me the papers, from which I unearthed a melody that somewhat matches the partial lyric that Cromer recalled for the intriguingly titled “A Girl Who Doesn’t Ripple When She Bends.” The melody was catchy in exactly the fashion that one associates with Waller, easy to imagine as the background to a number preserved in a photo, in which fetching females do calisthenics as a black man in a turban tap-danced (it was that kind of show). The box also includes four fully harmonized melodies, all Waller-solid, not used in the production.

In December 1943, six months into Early to Bed’s run, Waller suffered a bout of flu and bronchitis while touring the West Coast and died of pneumonia on the train ride back east. He was only 39. The timing of his demise was particularly unfortunate because, while Waller biographers rarely stress the fact, writing for Broadway would have been the next chapter in his career.

In the early 1940s, jazz was developing into the spiky, allusive genre called bebop, with a new harmonic complexity, rapid-fire chord changes, and a focus on the instrumental more than the vocal. Waller was unlikely to have embraced it wholeheartedly. Connecting with the audience through singing and humor were integral to his performance persona, and musicians of his generation tended to find bebop chilly and athletic for mere athleticism’s sake. Meanwhile, work for traveling bands, such as the one that Waller made much of his living from, began drying up a few years after he died.

Where would that have left him? He was a spellbinding presence on film, and today we savor his appearances, especially in Stormy Weather, but in the 1940s and 1950s, cameos and subsidiary roles were all that black comics and musicians could hope for in mainstream cinema. Perhaps Waller would have landed his own show when television emerged. He had hosted a successful radio program in the 1930s. The first black host of a television show, in 1948, was none other than the man who performed the role that Waller was to have played in Early to Bed: Bob Howard, a singer-pianist-entertainer whom the Decca recording company promoted as competition for Waller in the 1930s. Film clips of his performances reveal a virtual imitation of Waller’s sound and mannerisms. Waller might have been sought out for precisely that job, or a similar one, had he lived—though it likely wouldn’t have lasted long, in a time when black performers drew limited interest from viewers and wan commitment from networks and sponsors.

If Waller had lived longer, then, he would almost certainly have faced a career crisis by about 1950, but for one trump card: Broadway. Waller’s gift for melody was equal to that of esteemed Broadway composers whose stars rose after World War II, such as Richard Adler and Jerry Ross, Jule Styne, or Harold Rome, and superior to that of many composers who saw their work enshrined in Broadway scores in the 1940s and afterward, such as Morton Gould, Robert Emmett Dolan, and Albert Hague. Waller could have had further hit shows. Kollmar thought so; he had been negotiating for Waller to compose for a white show starring Libby Holman as well as for a black show. As ever more musicals were recorded as cast albums, such recordings would have cemented Waller’s new status as a composer for the “Main Stem.” Even the evolution of musical theater in the 1940s and beyond would have complemented Waller’s own. As theater scores explored broader ranges of emotion, Waller could have found an outlet for his yearning, later in life, to pursue more serious directions. His acetate recording of the up-tempo, unused Early to Bed song “That Does It,” for example, has an unexpectedly quiet, trailing coda, a mood and contrast that would have been effectively applied to the kinds of character songs that Broadway composers were starting to write.

More Broadway musicals from Waller would have shifted the landscape for black composers: in his absence, in the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s, blacks had almost no creative presence in Broadway musicals beyond performing. Other black musicians—in classical music as well as in pop and jazz—may well have been inspired by Waller’s example to experiment with the form. Just as likely, white producers would have actively sought out such talent in an effort to channel Waller’s success. Duke Ellington may have been offered more projects and gotten luckier than he did with the failures Beggar’s Holiday and Pousse-Café. Rhythm and blues composer Louis Jordan could also have transferred his abilities to stage music instead of settling—posthumously—for seeing his music adapted for an anthology revue, Five Guys Named Mo.

Would racism have blocked Waller from joining the leagues of Broadway composers? He was certainly no stranger to it. After the Boston tryout premiere, he and his family had been refused entry into the hotel that he had reserved when the staff learned that he was black. He was similarly barred from other hotels and had to spend the night in a flophouse. But where business was concerned, things were somewhat different. When it came to song hits, money talked, even in 1943. Given that Waller’s race hindered the success of Early to Bed not one bit, there is no reason to suppose that it would have interfered significantly in the backing and mounting of future stage shows.

In other words, Early to Bed, forgotten today, could have been the beginning of an important moment in the development of American theater music, as well as of opportunities for black musicians in an era when slow but steady civil rights victories were making integration an American reality. One can imagine old clips on YouTube of Waller singing and playing songs from his latest Broadway show on 1950s variety programs like the Colgate Comedy Hour. Instead, fate dictated that Early to Bed was the end of a story rather than the beginning.

That story should at least be gotten down for posterity. In an era that has seen dozens of recordings since the 1980s of old and often obscure Broadway scores, using original materials or re-creating them where necessary, Early to Bed’s songs deserve a recording, in period style, with the gaps filled in by other lesser-known but effective songs written by or associated with Waller. Also, archivists, collectors, and hoarders across America should be on notice for manuscripts of the four missing songs from the score—and maybe even a long-lost copy of the score itself.

It would be worth it, and I should know: I produced a small-scale re-creation of the score for a cabaret space some years ago and can attest that Waller’s work still delights a modern audience, including listeners with no particular affection for musical theater. The utter obscurity of Early to Bed is a loss not only to scholarship and the heritage of black artistry but to our listening pleasure.

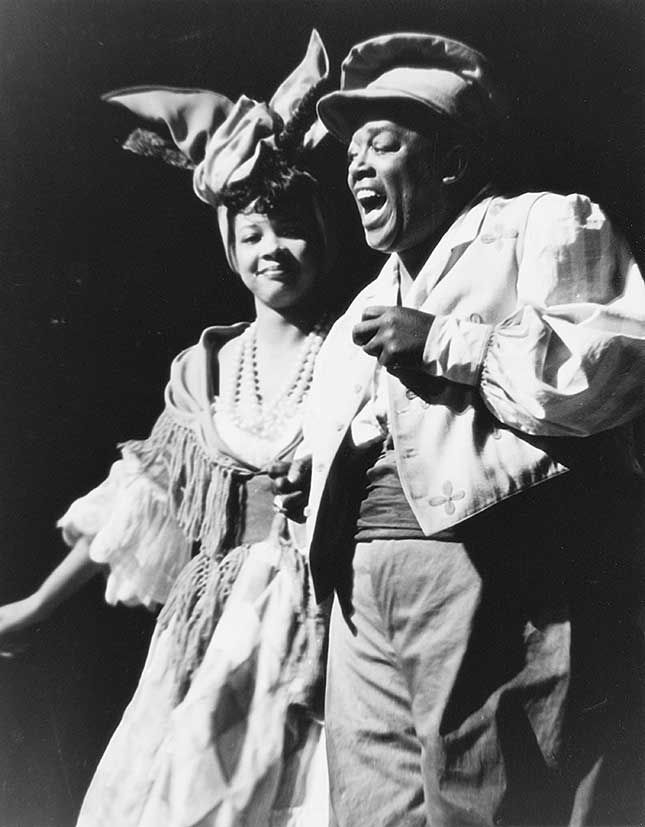

Top Photo: Fats Waller in 1943 (GEORGE RINHART/CORBIS/GETTY IMAGES)