The Hirschfeld Century: Portrait of an Artist and His Age by David Leopold; Alfred A. Knopf; 320 pages; $40.00

As the painter Paul Klee saw it, a line was simply “a dot out for a walk.” In the case of Al Hirschfeld (1903–2003), that walk lasted 86 years, every one of them a triumph of perception and draftsmanship. The doyen of theatrical caricaturists is currently being celebrated in two ways, one on walls, the other between cloth covers. The New York Historical Society has opened its autumn season with an exhibit of Hirschfeld’s drawings and paintings, produced over nearly nine decades—longer than Picasso’s creative period. And while it’s true, as comedian George Burns observed, that “Hirschfeld was no Picasso,” he added, “but then, Picasso was no Hirschfeld.”

Just before World War I, the Hirschfeld family moved from St. Louis to New York. Developing an interest in sculpture, young Al took a few courses at the National Academy of Design. One day he came to the realization that “sculpture was just a drawing you could trip over in the dark.” Turning to illustration, the wunderkind immediately caught on, freelancing posters for silent movie studios, among them Goldwyn, Selznik, and Universal Pictures. Within a few years he became noted for an elegant use of light and shadow and for sketches of celebrities who seemed to be in perpetual motion. Nearly a century later, Laurel and Hardy still caper merrily, Charlie Chaplin grins manically, Norma Shearer emotes lyrically—each recognizable, yet exaggerated in a new style.

Looking back, Hirschfeld once remarked, “The whole trick in art is to stay alive. If you live long enough, everything happens, the drawing improves, life improves.” So it did for Al. Decade after decade his work got sharper and more economical. He captured Broadway opening nights for the Sunday New York Times and Hollywood performances for any publication that would pay his fee, from TV Guide and Saturday Review to The New Yorker and Time. On each occasion he used the ingredients of another show-business illustrator, Toulouse Lautrec: affection, insight, wonder, and genius, plus a soupçon of salt.

Take for example, Al’s saucy portrait of the Marx Brothers in the MGM lobby card for A Day at the Races. The studio shot of Groucho and his foil, Margaret Dumont, looks like an antique brought down from the attic. Next to it is a Hirschfeld caricature of the siblings peeking out from a curtain. It remains as fresh and funny as the day it was drawn.

Accompanying the Society’s exhibit is a lavishly illustrated volume, The Hirschfeld Century. The scores of pictures are, of course, by the honoree; the text is by curator and Hirschfeld authority David Leopold. He points out that today, “Millennials look more at Hirschfeld drawings as art rather than as records of specific performances, not having had a lifetime of seeing drawings herald the latest opening. Al’s goal was a drawing that ‘could stand on its own two feet,’ and time is now showing how successful he was.”

When I interviewed Hirschfeld for the Oscar-nominated documentary of his life, The Line King, he made a point of stating, “I don’t know how the hell I do what I do.” Working in blissful ignorance, he captured the essence of explosive performers like Carol Channing, Zero Mostel, and Luciano Pavoratti—and followed that by presenting the entire cast of Hair without a single recognizable star. He drew African-Americans without the use of cross-hatching or shading, Christopher Plummer playing John Barrymore so that the picture miraculously resembled both men, and offered a self-portrait of the artist turning his brain into an inkwell and dipping his pen in it. Each time, the production seemed to surprise him as much his devotees, a burgeoning group of academics and art critics, along with millions of readers who just liked to be amused.

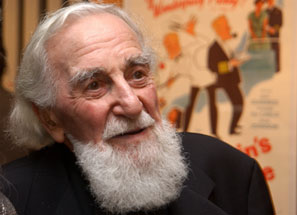

As he aged, Al became more recognizable than his subjects, turning from a black-haired Svengali type to a white-haired gentleman described by humorist S. J. Perelman as “a pair of liquid brown eyes, delicately rimmed in red, an innocence to charm the heart of the fiercest aborigine, and a beard which would engulf anything from a tsetse fly to a Sumatra tiger. In short, a remarkable combination of Walt Whitman, Lawrence of Arabia and Moe, my favorite waiter at Lindy’s.” That combination could cause an audience buzz every time he and his wife, actress Dolly Haas, assumed their orchestra seats.

Watching the behavior of show folk on and off stage, Al learned the value of publicity. The name of the Hirschfelds’ only child, Nina, began to appear in all the caricatures, often five or six times in the same drawing, hidden in the coiffure or costume of an actress, in the suit of her co-star, or in the scenery. Readers spent many a Sunday morning trying to find them.

What they never found was the underlying reason for Hirschfeld’s achievement. He kept it hidden for the century that his life embraced. His talent was such that he could easily have become the greatest political cartoonist of his time. But as he acknowledged, he lacked the venom for partisan sniping. With his gift for color and décor he could easily have become one of America’s major designers. But that would have kept him from the third floor studio in his 95th Street house where, seated on a barber’s chair, he continued to organize prominent figures within the strictures of an oblong space.

Besides, as Hirschfeld saw it, he had enough money, a good job, grandchildren, and after Dolly died, a happy second marriage to theater historian Louise Kerr, 33 years his junior. If there was nobody to take his place in the years to come, well, so be it. Asked whether he ever thought about retiring, the nonagenarian had the same reply as the octogenarian and the septuagenarian: “How could I forsake those opening nights?”

Embedded in those lines was Al’s secret. He was not merely an artist of the stage, he was a devotee. Aisle-struck from Night One, he turned into a performance artist himself, and the tale of his life and career is one of the great love stories of the twentieth century. Best of all, that affection was requited. Ticketholders to Kinky Boots can see the evidence every night as they gaze at the marquee of the Hirschfeld Theater on 45th Street. It was dedicated in 2002, the year before Al died at the age of 99, productive to the end, a caricature of the Marx Brothers lying unfinished on his drawing board.