In his first state of the city address, earlier this year, New York City mayor Bill de Blasio, picking up on the theme he’d repeated so often during his successful mayoral campaign, decried the existence of “two New Yorks”: one for the rich and the other for everyone else. The new mayor expressed empathy for the city’s “squeezed” middle class, in danger of vanishing because of a lack of good jobs and the difficulty of making ends meet in an urban economy characterized by “skyrocketing rents” and other rising costs. Nor did he forget the poor. He would work to “lift the floor for all those struggling” in today’s New York, the mayor promised; everyone would get “a fair shot” in his fairer city.

Throughout his speech, de Blasio said little about what he thought was causing the city to get so unaffordable for so many. If he’d been honest with himself, though, he would have to see the very government that he leads—and the expansion of which he enthusiastically supports—as a major contributor to the economic difficulties of the city’s non-wealthy, especially middle-class families. From its arcane regulatory regime to the nosebleed taxes and fees it imposes on firms and individuals—usually amplifying similar measures radiating out from the state government in Albany—New York City government drives up the cost of living and working in the city dramatically, making it harder for ordinary New Yorkers to get ahead. Unfortunately, the mayor’s policy agenda—demanding that businesses grant employees paid sick leave and compelling real-estate developers “to build affordable homes for everyday people,” among other steps—will only make the problem worse.

New York is unquestionably a city with substantial inequality. A new Brookings Institution study ranked it fifth among the nation’s 50 largest cities in the gap between rich and poor, as defined by the disparity between the average household income of those in the 20th percentile of earnings (a household that earns $17,119 annually in New York) and a household in the 95th percentile ($226,675 annually in New York). A similar study last year by demographer Richard Morrill for Newgeography.com ranked the New York metro area as having the widest wealth differences as expressed by the Gini Index, a measure of income distribution.

The paucity of reasonably priced living arrangements in the city has much to do with this striking income disparity. A recent New York Times story, summing up research on urban income differences, noted that income inequality “is closely tied with the availability of affordable housing.” Places where housing becomes very expensive, the report observed, tend to hemorrhage middle-class residents and instead become communities made up primarily of the rich, who can afford stratospheric housing prices, and the poor, who can get government housing subsidies. And New York, according to information from real-estate website Trulia that the Times cited, has the highest housing prices, relative to incomes, of any American city except San Francisco. In New York, the typical middle-class family can afford only about a quarter of available homes, the data suggest. True, rents are cheaper—or, at least, they are in the city’s nearly 1.1 million rent-controlled, rent-regulated, and rent-stabilized buildings. The average apartment of this type rents for about $1,100 per month. That’s great for the people living in these apartments (which represent nearly half the rental units in the city). But the average asking price for an unregulated apartment in the city is $3,000 per month—nearly three times the national average. Small wonder the renters with the deals rarely give up their places. This reality clearly helps explain why, as a McKinsey analysis of census data last year found, the number of New York middle-class families—those earning between $35,000 and $75,000 in income— fell from about 940,000 in 2000 to about 875,000 by 2012.

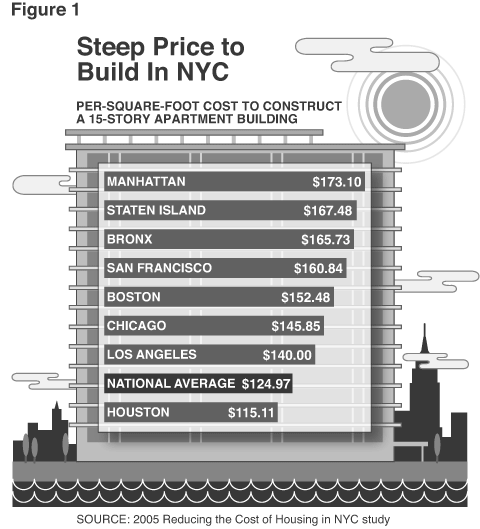

Mayor de Blasio usually—and correctly—describes New York’s high housing costs as a major contributor to the “two New Yorks” problem. The villains behind those costs, in his view, are “gentrification, unscrupulous landlords, and the real-estate lobby’s hold on government,” as he put it in his state of the city address. Yet de Blasio neglected to mention a far more significant reason that housing is so pricey in New York: it’s incredibly expensive to build in the city. Perhaps the most comprehensive examination of New York construction costs is a 2005 study by three policy experts from the New York City School of Law, released under the auspices of New York University’s Furman Center for Real Estate and Urban Policy and the Robert F. Wagner Graduate School of Public Service. The report found that the price tag for building a 15-story, multiunit apartment building in New York had become the highest of any city in America (San Francisco was second). In fact, the study found, erecting such a building was costlier in any of New York’s five boroughs—even in the Bronx, the poorest—than elsewhere. The Bronx bill was nearly $20 higher for every square foot than in Chicago, for instance, $26 more than in Los Angeles, and a whopping $55 higher than in Dallas (see Figure 1). With some 150,000 total square feet in a building of this size, those differences equal a lot of money—as much as $8 million extra to build in the Bronx and not Dallas. Construction prices have risen by about a third across the nation since 2005, but recent surveys show that New York maintains its substantial lead over other cities.

Needless to say, the expense pushes up rental rates in the city’s unregulated apartments. A 2010 study by the Association for Neighborhood and Housing Development estimated that covering the cost of financing, building, and operating a new apartment building in New York City, including taxes, required a minimum rent for its units of $2,100 per month. To live comfortably with such rent, a family would need an income of at least $86,000. Further, developers become understandably unwilling to construct apartment buildings where they can’t be assured of such rent premiums. The high construction costs result not only in inflated rents in new buildings, therefore, but in an overall shortage of housing, which drives up the price of already-constructed unregulated units.

And it’s New York’s tentacular state and local government that helps make it so wildly expensive to build. The NYU study found a host of government policies that drive construction prices higher. For starters, city agencies responsible for overseeing and regulating building were often openly hostile to new construction, the study discovered. “The Buildings Department is still one of the major drivers of the high cost of housing in New York City, rather than an agency dedicated to reducing expense and facilitating development,” the report observed. Even experienced builders, the study found, now typically employed well-paid “expediters” to move their projects through the city’s foot-dragging approval process, adding an average cost of about $200,000 per building.

Taxes and fees tied specifically to development—many of them rare in other cities—are another factor in Gotham’s sky-high building costs. For example, New York levies a transfer tax on land when a developer buys a plot, and then a mortgage-recording tax when a builder borrows to finance his project. And the builder faces significant sales taxes on construction materials, too. For a hypothetical New York apartment building, going up on a plot of land bought for, say, $5 million, real-estate, mortgage, and sales taxes would add $1.6 million to the development price tag.

New York’s local and state elected officials also write laws and codes that curry favor with various special interests with a financial stake in development, raising prices higher still. Litigation-friendly New York State makes it easy to sue builders and developers, for instance, which benefits construction-worker unions and trial lawyers, two powerful Albany lobbies, but makes insurance on the construction of an apartment building as much as 8 percent to 10 percent of total costs—twice the national average. The Scaffold Law may be the most striking example of this kind of legislation. Unique in the country, it mandates that a developer or contractor is completely liable if an employee gets injured on a job site, even if worker negligence played a role. Even workers found to be drunk on the job have won big judgments.

Another costly government barrier to building is the city’s excessive fondness for historic preservation. Initiated in the mid-1960s as a way of protecting truly exceptional structures—a fallout from the unfortunate demolition of the original Penn Station—the city’s landmarking process has morphed over time into a way for local activists and progressive politicians to stymie development of any new construction in neighborhoods often all but devoid of historic value. Nowadays, notes Harvard economist and City Journal contributing editor Edward Glaeser, nearly 16 percent of buildable land in Manhattan resides in historic-preservation districts, and about half of it is largely off-limits to development. (See “Preservation Follies,” Spring 2010.) In a city desperately needing housing construction, the preservation districts lost an average of 46 units of housing per tract during the 1990s, according to Glaeser’s research. Not surprisingly, the cost of housing in these districts has risen substantially faster than in other areas of the city.

The authors of the NYU study calculate that easing or eliminating the impediments that they identified could reduce housing construction expenses by 19 percent to 25 percent—a massive savings. Further, they add, these figures “likely underestimate the full impact of the recommendations because they do not take into account the supply effects of the proposals to make additional land available for residential use.” If enacted, the changes could cause rents to fall by as much as 26 percent, the authors projected.

De Blasio’s response to the affordable-housing problem isn’t to make it easier to build; it’s to harangue “greedy landlords” and propose cutting housing costs at their expense. He’s stocked the city’s Rent Guidelines Board with tenant-friendly commissioners and demanded that they freeze any rent increases in those buildings subject to rent regulations. The mayor’s plan might indeed hold down tenant costs in the regulated apartments. But it does nothing to restrain the steadily rising expenditures that the apartments’ landlords face, especially those imposed by the city. Over time, such an approach will lead to more housing-affordability problems, not fewer, as history has shown.

“My name is Matiur,” a landlord who owns a rent-regulated building with six apartments in Queens testified to the rent board last year. “I moved to the United States from Bangladesh 36 years ago and have owned my building since 1997. Unfortunately, low rents [including one apartment that rents for just $280 a month] make it impossible for me to maintain my building.” Landlords worry about the city’s rising taxes on multiunit residences—increases that outpace rents. Since 2003, property-tax collections in the city have soared from $9.9 billion to $19.8 billion, thanks to rising assessments and a major tax increase engineered by the Bloomberg administration. As landlord Michael Vinocur said at a rent hearing last year, “My taxes are 80 percent higher now than five years ago, and my rent revenues have gone up less than 20 percent.”

The last New York City mayor to try something similar to de Blasio’s rent controls for a sustained period was John Lindsay, back in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Lindsay’s administration vastly expanded the housing subject to rent regulations, and then watched as the city’s Rent Guidelines Board kept rent increases below the spiraling costs that landlords had to pay during that era of high inflation and tax hikes. The city then endured its greatest housing losses in history, as landlords, unable to meet their bills, abandoned some 300,000 units of housing between 1974 and 1984. Hardest hit were small landlords, many of them first-generation immigrants of modest means. They lost buildings because of unpaid taxes and mortgages—and with the buildings went their savings and dreams. Renters suffered, too, as the supply of adequate housing fell.

The damage from the abandonments required billions of tax dollars to mitigate. During the mid-1980s, Mayor Ed Koch’s administration rolled out a ten-year, $5 billion rebuilding program, which City Journal later estimated cost double that amount, thanks to debt service, tax subsidies, and administration. The program fundamentally changed housing in New York: small landlords who had once owned the buildings were replaced by dozens of nonprofit housing groups. Many of the renovated properties thus remained off the tax rolls, even after they reopened. Housing became another highly politicized part of city government, with favored groups, handpicked by the government, receiving the best contracts and renting to tenants of their choice.

The renovation program did little to address New York’s numerous disincentives to private development. Meanwhile, housing constructions shriveled. From 1961 through 1965, builders completed an annual average of nearly 47,000 new units of housing in the city. After Lindsay took office in 1966, production slumped to fewer than 21,000 units annually during the rest of the 1960s, 14,000 units during the 1970s, and just 8,700 units during the 1980s. By the mid-1980s, a city study estimated, Gotham’s housing market was short some 231,000 units. Since then, the city’s housing production has never averaged even half of what it was in the 1960s, leaving a perpetual shortage, for which a succession of government-subsidized building programs have yet to compensate.

New York puts additional pressure on residents and businesses through its extraordinarily high taxes, which ripple throughout the economy and raise prices for everyone, “everyday people” included. A 2007 study by the city’s nonpartisan Independent Budget Office found that New York City and State combined take 90 percent more in taxes per $100 of productive income from Gotham residents than the combined city and state tax bite on residents of other large American cities, including Los Angeles and Chicago—hardly low-tax environments.

The main reason: New York’s personal and corporate income taxes. New York City and State collect more than three times as much from city residents in income taxes—$3.12 per $100, compared with 95 cents—than in large cities elsewhere. This burden falls not only on the rich but also on middle-income families. A study by the chief financial officer of Washington, D.C., comparing tax rates in major American cities found that the total state and local tax bite on a family in New York earning $75,000 a year was $1,800 higher than in other major cities. For a family earning $100,000 annually—hardly plush in New York—the typical tax burden was $2,850 higher annually than in other big cities. In New York, the IBO study found, state and local government takes, on average, 120 percent more in taxes per $100 of income than is taxed in Houston.

New York imposes other strains on non-wealthy residents in the form of additional heavy business taxes and fees and intrusive business regulations. These measures curb job growth—above all, in middle-income occupations—and make it tough for new firms in the city to survive, let alone flourish and provide their owners with an entrepreneurial route to the middle class. The IBO study found that New York levies business taxes at nearly double the average found in other big cities—$1.06 per $100 in taxable income, compared with 55 cents per $100.

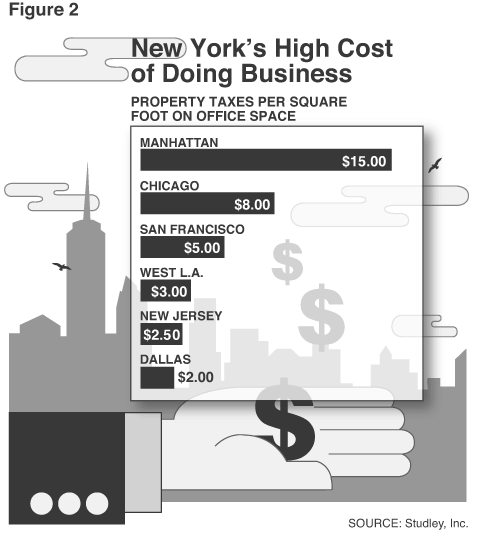

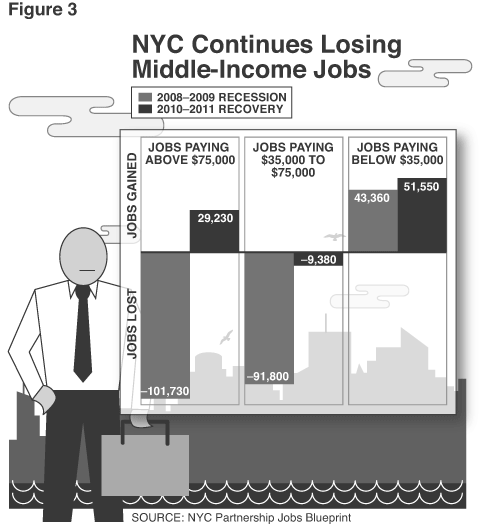

Property taxes for office buildings take a huge bite. On average, New York City charges Manhattan firms that rent office space $15 a square foot just in real-estate taxes, according to research by Studley, Inc. By contrast, property taxes for office tenants in Chicago’s main business district average $8 per square foot, in San Francisco just $5 per square foot, and in Dallas $2 (see Figure 2). In nearby suburban New Jersey, a direct competitor with New York for many middle-income office jobs, the tab is just $2.50 per square foot. A modest-size firm employing 400 and renting 100,000 square feet of space will pay, on average, $1.25 million more in property taxes in New York than it would in suburban New Jersey. This occupancy bill is a major reason that middle-income jobs are disappearing from Gotham, a report last year by the New York City Partnership found. Since 2008, New York has lost 91,800 middle-wage jobs (see Figure 3). Most of those jobs disappeared during the recession that stretched from 2008 through 2010 in New York, true; but the city has kept losing them during the subsequent recovery, even as other sectors of the economy have bounced back. Companies remain willing to keep their highest-paid executives in New York because those workers thrive in a global business capital, and low-income jobs for unskilled workers follow because the city still needs service workers—those employed by restaurants, retailers, and hotels—to provide basic amenities. But companies derive little payoff from keeping middle-income jobs in pricey New York when technology allows them to situate these positions in less expensive locales.

This pattern is stark in financial services, New York City’s most important industry. Financial firms began migrating out of the city in the 1970s, when New York State, at the urging of city politicians, slapped a tax on stock trades. Though the state ultimately repealed the levy, firms continued to move workers out, especially mid-level back-office employees, as the cost of providing work space for them grew. Over the last 20 years, while financial-services employment declined by 35,000 jobs, or 7 percent, in New York City, the industry grew by 30,000 jobs, or 14 percent, in neighboring New Jersey. Average pay in Manhattan for a financial-services job is now $246,000 annually; in New Jersey, the securities industry is more of an upper-middle-income business, with average pay at $97,600 annually.

It’s also incredibly cumbersome to start a business in New York City. A recent study by the finance site WalletHub.com ranked New York a discouraging 126th out of America’s 150 largest cities in the ease of launching a firm. A recent World Bank report noted that a would-be entrepreneur needs to obtain six permits, on average, to start a new venture in the United States (compared with just one in business-friendly New Zealand). But according to NYC Business Express, he’d need ten—six local and four from the state—to open, say, a simple office-supply business in the city. A study by the Kauffman Foundation and Thumbtack.com gave New York City a D for welcoming entrepreneurs.

All these impositions and requirements snuff out growth and opportunity. The NYC Jobs Blueprint study released by the Partnership for New York City last September estimated that it costs 50 percent more to build a business in Gotham than in the U.S. in general. One consequence, the study pointed out, is that New York businesses aren’t “scaling up”—that is, they’re not growing larger at an encouraging rate. Between 2003 and 2010, New York City saw no rise in the number of firms with 50 or more employees. Another worrisome sign: the city experienced a net loss during that time span of so-called tradable companies—firms in industries with the capacity to do business outside the five boroughs, and hence possessing the largest growth potential. “Because companies in a high-growth mode need all available resources to invest in people, New York is less attractive as a job expansion location than lower cost alternatives,” the study observed.

Putting still another strain on ordinary citizens, New York’s government pushes up the prices at establishments that do business directly with consumers, such as retailers and restaurants. For decades, the city’s politicians have tended to meddle in these industries for their own political aims, often keeping out disfavored firms and squelching competition. During the 1990s, for instance, city officials fought among themselves and with neighborhood business groups over plans by the Pathmark supermarket chain to open an outlet in East Harlem, which had lacked a major supermarket since the 1960s, despite the $3 billion or so annually that its residents spent on food. That Pathmark couldn’t open “as-of-right”—that it needed to win the support of politicians before it could operate—illustrates why New York, one of America’s densest cities, is still underserved in key business categories such as food retailing. A 2009 study by the Bloomberg administration estimated that New York needed 100 more supermarkets to serve its residents adequately and was losing $1 billion in sales a year as shoppers left the city to buy food.

New York’s political class has similarly thwarted the efforts of America’s largest retailer, Wal-Mart, to open a branch in the city. Elected officials, many backed by labor organizations, have justified denying permits to the firm by charging that it exploits working people and ruins neighborhood prosperity. “Wal-Mart has blazed a path of economic and social destruction in towns throughout the U.S,” then-congressman Anthony Weiner told the New York Times in 2005. New Yorkers, however, think far more highly of the retailer. In 2012, the company says, basing its finding on credit-card receipts, city residents spent a staggering $215 million at its New York metropolitan area stores outside the city. And surveys show that New Yorkers overwhelmingly want the stores, with their low prices and broad selection.

The higher prices that inevitably result from these restrictions on commerce are a substantial burden to ordinary New Yorkers, who can’t regularly leave to shop in the suburbs. Just compare the cost of basic necessities in New York with that in other cities, especially those considered to have low levels of inequality, like Houston, Oklahoma City, Las Vegas, and Colorado Springs. The website Expatistan.com’s cost-of-living index estimates that the average price of a quart of milk is 55 percent higher in New York than in Las Vegas, while eggs cost 34 percent more per dozen than in Houston; two pounds of apples cost 22 percent more in New York than in Colorado Springs. New York City retail costs are considerably higher even than other overregulated, heavily taxed metro areas such as Los Angeles, where food purchased at home or in restaurants costs 11 percent less. A 2006 Brookings Institution study of the impact of high prices on the urban poor maintained that New York’s high costs were a function of poor policies and could be fixed, if the city had the political will. “To lower these prices, public and private leaders must reduce the higher business costs that drive up prices for poor families,” the Brookings report noted.

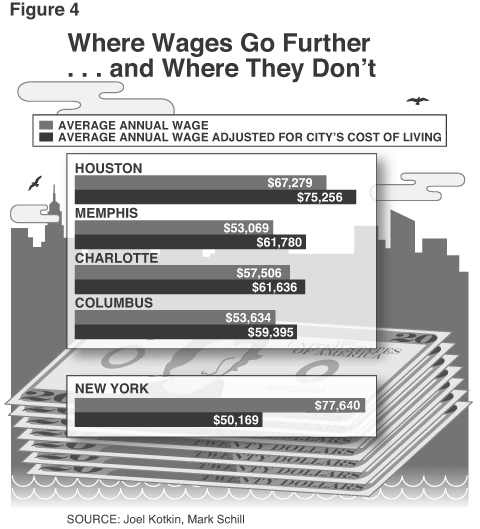

All these factors—the expensive housing, fat tax bills, and high prices—have a direct and powerful effect on people’s daily lives. In a 2008 City Journal article, Glaeser calculated that, after including the costs of housing, taxes, and transportation, the average Houston family wound up with 50 percent more income to spend than the average New York family. The difference in real dollars: about $32,000 in spendable money for the typical Houston family, compared with just $21,000 for the New York family. (See “Houston, New York Has a Problem,” Summer 2008.) In a similar study of median incomes adjusted for cost of living in 50 metro areas, City Journal contributing editor Joel Kotkin and the Praxis Strategy Group’s Mark Schill determined that Houston workers enjoyed the nation’s highest effective pay: the annual average Houston salary of $67,279 was worth $75,256 when adjusted for the city’s lower-than-average cost of living. By contrast, in New York, the average annual salary of a worker, $77,640 on an unadjusted basis, shrank to $50,169 when corrected for the city’s high costs—above all, housing and taxes (see Figure 4). That left New York a poor 41st among metro areas in average annual effective pay.

Mayor de Blasio’s policies will only make New York more expensive and unequal. One of his first acts in office was to impose the city’s new mandatory paid-sick-leave law on all firms with five employees or more. De Blasio and the city’s new progressive coalition of city council members, most with zero private-sector experience, defended the law on the grounds that one way to alleviate inequality in the city is to have businesses “share a little better,” as the cochair of the city council’s Progressive Caucus, Brooklyn City Councilman Brad Lander, put it. But this notion vastly underestimates the difficulties of doing business in the city—difficulties that have only worsened since the 2008 financial crisis, with business failures soaring 40 percent in the meltdown’s aftermath, according to Dun & Bradstreet. Many firms, including eateries and supermarkets, run on very low profit margins and just don’t have much extra cash “to share.”

A survey by the NYC Hospitality Alliance estimates that providing five sick days for a restaurant with 12 employees will cost the establishment about $5,000 annually in wages alone. And that’s only part of the price tag. The city council also cynically amended the original paid-sick-leave legislation, passed under a previous council, to increase massively the paperwork necessary to comply with the requirements, while also making it easier for employees to sue firms by extending the time that they can file a complaint, from six months to three years. The legislation also empowers the city’s Department of Consumer Affairs to initiate its own investigations into how firms are complying with the law, even absent any complaints from workers—raising fears that New York government will use the legislation as another means to impose fines on firms for failing to keep adequate paperwork. “This legislation could create havoc with small independent supermarkets,” Zulema Wiscovitch, director of the National Supermarket Association, a coalition of 200 Hispanic markets, testified before the city council. “This burden falls on supermarkets just as they face other burdens, like the Affordable Care Act,” she noted.

Her pleas didn’t reach city council ears, though, because council members have so little regard for businesses—especially small minority operators—that they couldn’t be bothered to hear her testimony. At the council hearing where Wiscovitch spoke, about half the council members showed up to listen to testimony by the de Blasio administration. As soon as the administration’s representatives had finished, all but three council members walked out, before small-business owners had a chance to speak. “I want to thank the very few members of the committee who have chosen to stay here and listen beyond the administration, to hear what people actually have to say,” Rob Bookman, counsel to the New York Nightfall Association, observed as council members fled.

Given the almost mind-numbing instances of government intervention that drive up costs for average New Yorkers, the de Blasio administration has abundant opportunity for reform that would help residents live decent, affordable lives in Gotham. Many changes entail reducing or revamping regulations that wouldn’t even pinch the public purse. One place to start would be in housing, where the current administration can continue Bloomberg’s work of simplifying the city’s zoning codes to allow for more density in residential building while also streamlining building-approval procedures and letting builders correct construction-site violations before they get hit with hefty fines. The city should also eliminate excessive taxes and fees on the development process, such as mortgage-recording taxes, which drive up housing costs, and reform special provisions in New York State law, such as the Scaffold Law, which constitutes an excessive liability tax on building. Similarly, the city should remove barriers to the formation and operation of businesses by, among other things, reducing the number of licenses, permits, and fees that new firms must obtain or pay—especially for firms in office-based industries, which have a low impact on the surrounding environment—and by eliminating overly complex commercial zoning, which restricts where firms, especially retailers and other consumer-based businesses, can locate.

If the new mayor paid more attention to how New Yorkers are taxed, he would understand how heavily the city’s excessive levels of taxation fall on the non-wealthy and job creators. The city should lower its regressive local-sales levy, the sixth-highest city-based sales tax among the 100 largest municipalities in America. The tax hits especially hard on lower-income residents, who pay a larger percentage of their incomes on sales taxes than other households. Similarly, the city needs to recognize that the tax increases and assessment boosts of the Bloomberg years have driven both commercial property taxes and taxes on apartment and co-op buildings to stratospheric levels. During the first ten years of the Bloomberg administration, property-tax collections more than doubled in New York City, while in the same period nationally, those same taxes increased by only 60 percent throughout the country as a whole. As a result, New York has become increasingly unattractive for middle-income jobs because of the high cost of locating them in overly taxed office space, while higher taxes on city apartment dwellers have squeezed more and more families out of the market for reasonable housing.

Right now in New York, we’re living a tale of two cities,” Mayor de Blasio has declared. For him, those two cities are one for the rich and the other for the poor and the middle class. But perhaps the real dividing line in New York is between, on the one hand, ordinary citizens and business owners, struggling to make a go of it in one of the nation’s most expensive cities; and, on the other, perhaps America’s costliest and most intrusive government. What de Blasio doesn’t seem to recall is that the Charles Dickens novel he invokes is foremost a tale about the damage that a coercive government does to its own people.

Research for this article was supported by the Brunie Fund for New York Journalism.