It’s been clear for a while, at least since the collapse of Lehman Brothers last fall, that what we have to fear above all is hope itself. Attempts to trust that the worst is over and to stop frightening ourselves seem doomed to propel us into yet worse disappointment. We are not only unhappy, but—believing calm and happiness to be the norm—unhappy that we’re unhappy.

It’s time to recognize how odd and counterproductive is the optimism on which we have grown up. For the last 200 years, despite occasional shocks, the Western world has been dominated by a belief in progress, based on its extraordinary scientific and entrepreneurial achievements. But from a broader historical perspective, this optimism is an anomaly. Humans have spent the greater part of their existence drawing a curious comfort from expecting the worst. In the West, lessons in pessimism derive from two sources: Roman Stoic philosophy and Christianity. It may be time to remind ourselves of a few of their lessons—not to add to our misery but to alleviate our injured surprise and sorrow.

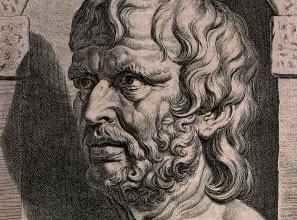

The Roman philosopher Seneca should be the author of the hour. Living in a time of continuous financial and political upheaval under the emperor Nero, Seneca interpreted philosophy as a discipline to keep us calm against a backdrop of continuous danger. His consolation was of the stiffest, darkest sort: “You say: ‘I did not think it would happen.’ Do you think there is anything that will not happen, when you know that it is possible to happen, when you see that it has already happened?” Seneca tried to calm the sense of injustice in his readers by reminding them, in ad 62, that natural and man-made disasters would always be part of their lives, however sophisticated and safe they thought they had become.

If we do not dwell on the risk of sudden calamity, in the markets and otherwise, and end up paying a price for our innocence, it is because reality comprises two cruelly confusing characteristics: on the one hand, continuity and reliability lasting across decades; on the other, unheralded cataclysms. We find ourselves divided between a plausible expectation that tomorrow will be much like today and the possibility that we will meet with an appalling event after which nothing will ever be the same. It is because we have such powerful incentives to neglect the second scenario that Seneca asked us to remember that our fate is forever in the hands of the Goddess of Fortune. This goddess can scatter gifts, and then, with terrifying speed, make a 50-year-old company disappear into a worthless asset, or let a balance sheet be destroyed by an evaporation of demand.

Because we are hurt most by what we do not expect, and because we must expect everything—“There is nothing which Fortune does not dare”—we must, argued Seneca, keep in mind at all times the possibility of dire events. No one should make an investment, undertake to run a company, sit on a board, or leave money in a bank without an awareness, which Seneca would have wished to be neither gruesome nor unnecessarily dramatic, of the darkest possibilities.

Secure in our financial prowess, we have for too long thought of ourselves as masters of our destiny. We have trusted in mathematical geniuses who promised us “risk management” and derivatives so complex that we didn’t dare to look inside. Such trust could not be further from a Stoic mind-set. We must, stressed Seneca, expand our sense of what may at any time go wrong in our lives: “Nothing ought to be unexpected by us. Our minds should be sent forward in advance to meet all the problems, and we should consider not what is wont to happen, but what can happen. What is man? A vessel that the slightest shaking, the slightest toss will break. A body weak and fragile.”

Christianity only reinforced the Stoic message. It pointed out that all human beings find it easy to imagine perfection, but that it’s a problem—indeed a sin—to suppose that such perfection can ever occur on earth. Nothing human can ever be free of blemishes. There cannot be an end to boom and bust.

We have tended to cast such gloomy messages aside. The modern bourgeois philosophy pins its hopes firmly on two great presumed ingredients of happiness: love and work (more specifically, a healthy bonus). But a vast unthinking cruelty lies discreetly coiled within this magnanimous assurance that everyone will discover satisfaction here. It isn’t that love and work are invariably incapable of delivering fulfillment—only that they almost never do for too long. And when an exception is misrepresented as a rule, our individual misfortunes, instead of seeming inevitable, weigh down on us like curses. In denying the natural place reserved in the human lot for longing and disaster, this philosophy denies us the possibility of collective consolation for our fractious marriages, our unexploited ambitions, and our exploded portfolios, and condemns us instead to solitary feelings of shame and persecution for having stubbornly failed to make more of ourselves.

We should instead remember the great pessimistic voices of history, of which I cherish two in particular. One is Seneca: “What need is there to weep over parts of life? The whole of it calls for tears.” The other is the French moralist Chamfort: “A man should swallow a toad every morning to be sure of not meeting with anything more revolting in the day ahead.”

Photo: mouse_sonya/iStock