I always enjoy the Biennial at the Whitney Museum. I learn a lot from the Whitney curators, the setting is gorgeous, and the vibe is often one of adventure and discovery. This year, it reflects a particular slice of Manhattan taste: ponderous, socially preoccupied in an abstract, opaque way, and joyless—though still worth seeing.

Today’s art, curator Jane Panetta writes in the Biennial catalogue, reflects the “intense national political discord, harrowingly heightened with the 2016 election and its aftermath.” Her co-curator, Rujeko Hockley, laments our “harsh and harrowing times,” adding, if we hadn’t gotten the point, “times are dark and dire.” We’re “lurching from one previously unimaginable horror to the next, steeped in vitriol and bile, hyperbole and confusion.”

Panetta promises that the show would touch all parts of the country, yet her essay is almost entirely about the Underground Museum in the mostly Latino and African-American Arlington Heights neighborhood in Los Angeles, and the hurricane in Puerto Rico. Nothing could be more remote from, say, my hometown in rural, poverty-stricken, opioid-wracked Vermont. The show has almost no rural subjects and very few artists from the spaces in between the two coasts.

Its anchor themes are predictable. The curators badly wanted to develop a show about race, gender, disability, access, and what they call “racial terrorism.” Times may be grotesque and horrible, the show implies, but since our opinions are so pure we’ll somehow survive.

It doesn’t start out well. “National Anthem” by Kota Ezawa takes a billboard-sized swath of wall space. It’s a watercolor animation of the “taking the knee” drama launched by Colin Kaepernick. The National Anthem plays loudly and mournfully enough to penetrate the entire floor. What’s the point except to diss the country?

Eddie Arroyo’s paintings of Little Haiti in Miami highlight, according to an accompanying label, “today’s neoliberal versions of colonialism, gentrification, which manifests itself in the eviction of longstanding residents, and the erasure of local architecture by new developers.” Without this label, with the pictures standing alone as aesthetic objects, these themes wouldn’t occur to anyone. The paintings are unobjectionable vernacular scenes. That gap between stated intention and what you see is a problem. First and foremost, these works are aesthetic objects, and they need to speak with authority and complexity on their own, without the ponderous didacticism of the labels.

Tomashi Jackson’s three paintings explore “parallels between the history of Seneca Village—which was founded in Manhattan in 1825 by free black laborers and razed in 1857 to make way for Central Park—and the city’s current government program to seize paid-for properties in rapidly gentrifying communities across New York, regardless of mortgage status.” Miss Marple herself wouldn’t detect any of this in the paintings. Moreover, the ostensible themes seem entirely unrelated, and it’s not clear why the city shouldn’t seize properties with unpaid taxes, standard practice everywhere. Here, again, in other words, the label is doing a lot of the heavy lifting, and giving the artist a verbal crutch to “tell” rather than “show” meaning through the art. I’d suggest visitors skip the labels altogether. Once unburdened by armchair sociology, I could savor Jackson’s flawless sense of color, shape, and material.

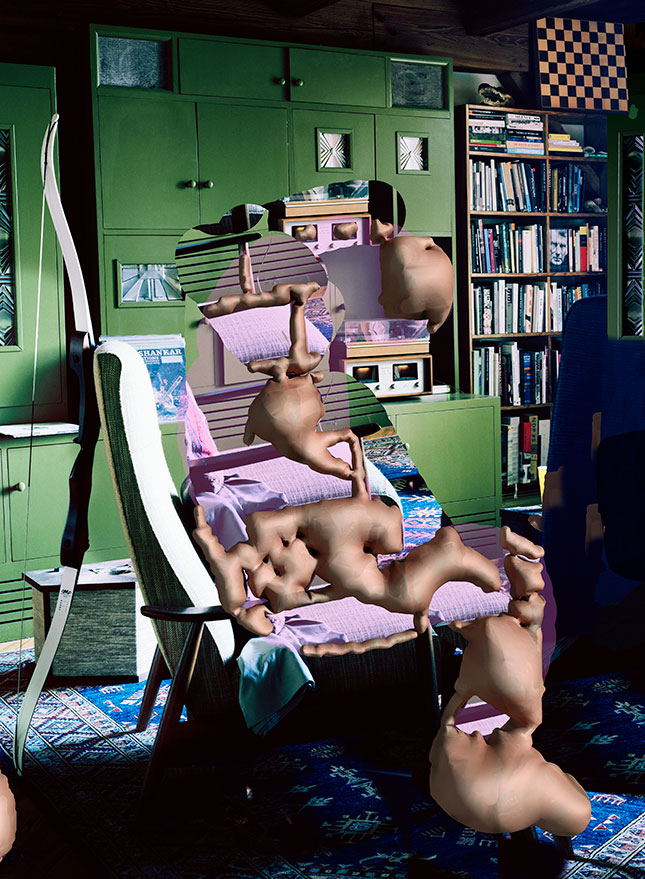

Mastery of medium abounds. I loved Lucas Blalock’s photography, if we can call it that. It’s something new, in fact, and it’s good. In “Portrait on the Street,” Blalock uses Photoshop the way an avant-garde painter uses brushes, paints, and knives. Objects form and dissolve in stunning eye-trickery. It’s the best abstract photography being done today. Paul Mpagi Sepuya’s photographic style, on the other hand, is precise and direct. He combines self-portraiture and a new kind of landscape: his studio. He’s a figure photographer in another novel respect, putting his camera in the composition. Brian Belott’s works suspend bits of things, collage-like—food, dollar store knick-knacks, paper—in blocks of ice. It’s an entirely new medium offering a new kind of sfumato, with a dash of Dada. Belott’s admits he has “a serious commitment to absurdity.”

There were many other delights. I thought Milano Chow’s work was elegant and stylish. She does graphite drawings with a touch of vinyl paint and some photo transfer. Part architectural drawing and part film set, depicting both interiors and exteriors, they have the magic, cryptic quality that keeps the viewer guessing and thinking. Todd Gray’s “Maya Venus” is a triptych of three overlapping inkjet prints, each framed by the artist. His work is so lush and striking that it takes a few seconds to see the three prints as comprising a single, exotic figure. Kyle Thurman’s big figure drawings were at the same time intricate and minimalist. He is a master of the simple line, deployed with just the right touch to create a figure with volume and feeling.

One of the best things in the show is the smallest. Jennifer Packer’s “An Exercise in Tenderness” from 2017 is a 9” by 7” painting, and a rebuke to the giantism that compels so many artists these days to work on room-sized canvases. She's a superb painter. I spent a long time picking apart that little thing in terms of her technique. The little drips of paint, juxtapositions of dabs of blue, white, red, orange, yellow, how thin so much of the paint is, how she creates a shape with weight and texture with a single brushstroke, all beautifully done, and a miniature, too.

The subject is a cop. Is it a man or a woman? Friend or foe? It's such a small painting, so precious. It's so tiny but she invests the figure with presence. Is this person to be cherished and loved? The police protect us, after all. Does Packer know the subject? She often does. She's a fine artist and young. She's come along in the last few years so I know she learns and changes.

Some artists are not at their best. Nicole Eisenman is a superb painter but here she’s represented by sculptural groups made of plaster, metal, and other materials. They’re grotesque enough to make me think of James Ensor or late Goya, but the figures are so oversized and hideous that they overwhelm whatever subtle points she’s trying to make—if there are any points beyond the desire to shock. I adore Simone Leigh’s sculptures of women in expansive hoop skirts, with touches of African Art, Southern folk art, and Baroque court portraiture. I was happy to see her included but hoped I’d find her next big thing rather than twists on her familiar themes, which might be getting old. Her new sculpture on the High Line is better.

Pat Phillips undermines his own considerable talent by trying to check a number of boxes: incarceration, servitude, the insulation of suburbia, the border with Mexico, “a violence that runs through our government and American culture,” among them. He’s trying to please his art-crowd fans when he should be leaping over the expected. He’s a superb painter with an inventive mind.

The oddest entry is Forensic Architecture’s film “Triple-Chaser.” It’s a film about Safariland, a company owned by Warren Kander, a Whitney trustee and donor. Safariland makes military equipment, including tear gas, and lots of people want Kander off the Whitney board because the government uses Safariland’s products to disperse mobs of illegal border crossers. I don’t care whether or not Kander is a trustee of the Whitney, but vetting trustees based on the sources of their money seems to invite a slide on a slippery slope. Doing so caters to people who are easily offended or have unsatisfiable grievances. Anyway, I don’t think this film is art. It’s a colorful, snappy documentary, the sort of thing you’d see on “Sixty Minutes.” Forensic Architecture isn’t American, either. It’s a British group, based in London. Why is its work in the show at all? I worked with many trustees and donors when I was a museum director and curator. Adam Weinberg, the Whitney director, was my predecessor as director of the Addison Gallery. Showing a film at the Whitney banging a funder over the head because of the nature of his business is the strangest form of donor stewardship I’ve ever seen.

The catalogue for the show is handsome and well-written, but over-designed. It has four sections, one comprised of illustrations of the artists’ work in the show, one on curator essays, one on each artist’s process, and one comprised of artist statements or biographies. To learn about a single artist, therefore, means flipping back and forth among the sections, which is a nuisance.

The catalogue is all about the designer, not the reader, which, I suppose, is not unlike the show itself. The curators have a point of view and a storyline—it just doesn’t match an America those outside their bubble would recognize.

Top Image: Lucas Blalock (1978-), Donkeys Crossing the Desert, 2019. Inkjet print on vinyl and app, 17 x 29 ft. (5.2 x 8.8 m). Image courtesy the artist; Galerie Eva Presenhuber, NY and Zurich; and Rodolphe Janssen, Brussels