Charter schools, critics have long maintained, exist to the detriment of traditional public schools. As the argument goes, charters—public schools, independently run (often by nonprofit organizations) and operating free of central district control but subject to government-accountability systems—siphon resources and the best students from local traditional public schools, degrading these schools for the students who remain in them. And charters harm the traditional public school system further by tossing back low-performing students.

“Both charters and vouchers drain away resources from the public schools, even as they leave the neediest, most expensive students to the public schools to educate,” Diane Ravitch writes in The New York Review of Books, in a representative formulation. “Competition from charters and vouchers does not improve public schools, which still enroll 94 percent of all students; it weakens them.” The pattern persists, Ravitch and other critics say, until it creates a death spiral for vulnerable, low-performing public schools.

Many charter opponents and others with an interest in perpetuating the current public school system find these arguments compelling. There’s one problem: empirical evidence points the other way.

Several extensive studies have measured the extent to which charter school expansion affects traditional public schools. Overall, the body of research suggests that competition from charters has a small positive effect on the performance of students remaining in traditional public schools. Choice helps many kids attend better schools, but it doesn’t seem to push traditional public schools to make dramatic improvements. At least so far, the results are not strong enough to support charter school proponents’ predictions that competition would force traditional public schools to improve substantially. And at least one study, by Scott Imberman of Michigan State University, found a negative impact from charter school competition. Imberman’s work is well designed and should be taken seriously, but even if he’s right, the magnitude of the negative effect is minimal and doesn’t justify the argument that charter school expansion destroys the ability of traditional public schools to educate their students.

Charter schools aren’t dumping their most difficult-to-educate kids on the traditional public school system, either, despite the prevalence of anecdotes to this effect. Analysis of enrollment data suggests that low-performing students are either as likely or slightly less likely to leave their school if it is a charter than if it is a traditional public school. Students with disabilities and those learning English as a second language are much less likely to exit charters than they are to depart traditional public schools. And prior academic achievement plays, at best, a trivial role in the probability that a student will enroll in a charter. The academic research, then, shows little reason to suspect that charter school expansion is harming, or will harm, students in traditional public schools.

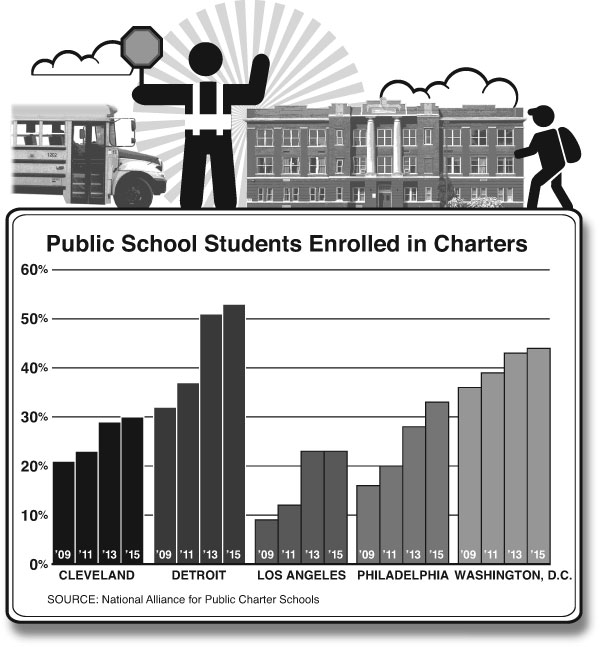

There are less specialized ways of looking at the issue. The charter sector has reached critical mass, making some reasonable assessment of its impact possible. While only about 6 percent of students enroll in charter schools nationwide, charters have attained significant market share in many localities. In seven school districts—including those serving Detroit, Kansas City, Philadelphia, and Washington, D.C.—one-third or more of students attend charters, according to a 2015 report from the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools. In 45 districts, at least 20 percent of students attended charters, and in 165 districts, charters had reached at least a 10 percent share of enrollment. So if critics are right, we should see evidence of negative impact on the performance of traditional public schools.

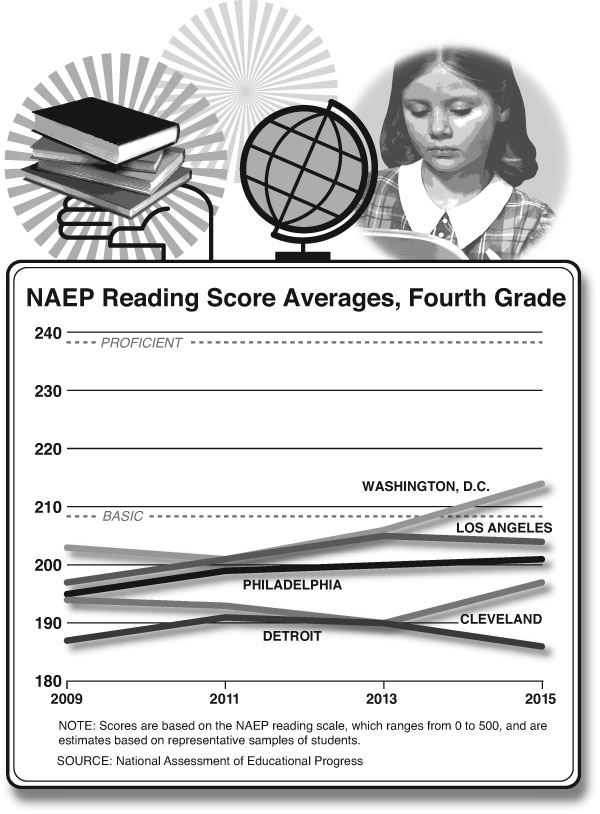

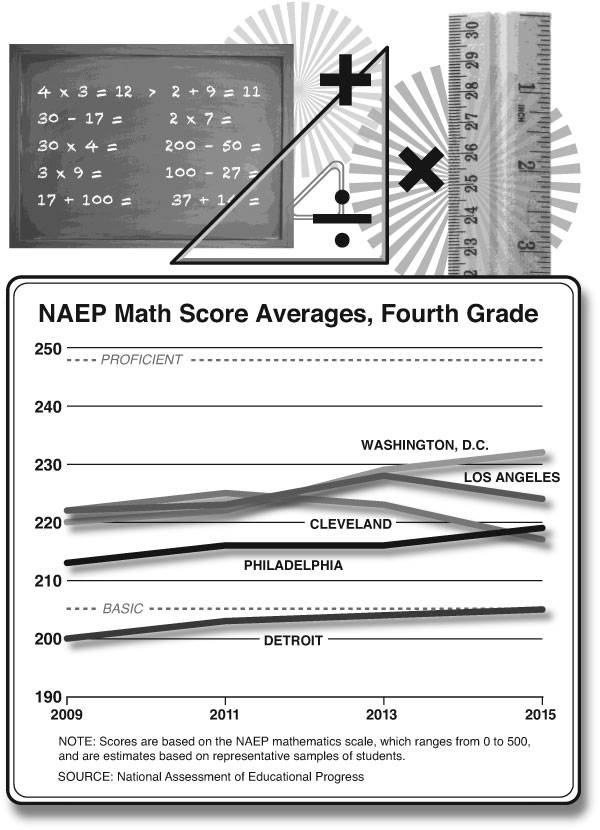

We don’t. Student performance in many cities with strong charter competition is either holding steady or rising. The accompanying charts display changes in five cities’ share of charter school enrollment, along with citywide public school scores on the federally administered National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) fourth-grade math and reading tests. All five cities—Washington, D.C., Philadelphia, Cleveland, Detroit, and Los Angeles—have seen substantial increases in charter enrollment in recent years. (Only a few cities administer the NAEP tests.) Performance varies across districts, with some substantial gains and some dips, but academic outcomes have not plummeted in any of these districts, and, in most cases, NAEP scores are improving. No death spirals are taking place.

We can’t say from these figures that charter school expansion is what caused the improved test scores in the cities where scores are rising. In Washington, for example, we know that other reforms, such as the introduction of a new teacher contract and performance-assessment system, have led to substantial improvements. But we can say this: if rapid charter school expansion truly represents an existential threat to local public schools’ ability to educate their students and if charters were really swallowing up the high-performing students and dumping the low-performers on public schools, then these charts would look different. We wouldn’t see traditional public school test scores go up, for instance, in Los Angeles—where charter schools’ share of enrollment has nearly tripled since 2009, from 8 percent to 23 percent.

New York City offers another example. The growth of charters in New York overall hasn’t been as rapid as in some other cities, but charter expansion has been substantial in certain neighborhoods with historically low-performing public schools. Today, about half of kids in New York City’s Community School District 5 (Central Harlem) attend a charter. Between 2012 and 2017, the proportion of New York public school kids scoring proficient or above on the state ELA exam increased from 13.4 percent to 24.1 percent. The proportion of students scoring in the bottom tier decreased from 52.3 percent to 39.3 percent. In math, the proportion scoring proficient or above grew from 13.1 percent to 17.3 percent; the proportion scoring in the bottom tier declined from 57 percent to 55 percent. In a recent study, Temple University’s Sarah Cordes found that these positive results are directly related to the increased competition that traditional public schools in the city face from charters. How do critics explain such improvements by local traditional public schools in districts where charters have attained significant presence?

Focusing evaluations on students in traditional public schools is shortsighted in a crucial respect: it fails to acknowledge that charters are public schools, too—one of many public-schooling alternatives offered to local residents. Charters are taxpayer-funded and open to all students (though subject to waiting lists, in many cases, due to excess demand). No one is forced to attend them; parents choose to apply, and enrolling in a charter takes time and effort. When a traditional public school system loses market share to charter schools, it means that a substantial proportion of parents believe that it’s in their children’s interest to seek alternative schooling options. Those who complain that charters take enrollments away from traditional public schools are saying, in effect, that parents should have to enroll their kids in what they see as less desirable schools.

“It’s about time that charter critics offer something more than anecdotes and theory to support their claims.”

Seen in this light, charters have made public schooling in Harlem and many other neighborhoods much better. Students attending Central Harlem charter schools, on average, are thriving. Harlem hosts many of New York’s, and the nation’s, best charter schools, including Success Academy Charter Schools, Democracy Prep, Harlem Children’s Zone, Harlem Village Academies, and the Knowledge Is Power Program (KIPP) charter schools. Research suggests that students attending these and other New York City charters are making enormous academic gains relative to how they would have performed had they remained in a traditional public school. Among the one-half of students in Central Harlem attending charter schools in 2016, 48 percent scored at or above proficiency, and only 15 percent scored in the lowest tier on the state ELA test.

Charter schools aren’t draining public education. They are revitalizing it.

If the vast majority of parents in a district were so dissatisfied with the regular public schools that they sought an alternative, and if enough space existed in those alternative schools to accommodate the students, then charters would, in their critics’ worst nightmare, “take over” the district. We’re a long way from something like that happening. Up to now, the only force proved capable of overthrowing a bad urban public school system and replacing it with charters is a Category 5 hurricane.

The New Orleans Parish public school system ranked among the nation’s worst as the new century dawned. In 2005, only 35 percent of students in New Orleans scored proficient or above on statewide tests (which set low proficiency standards), compared with 58 percent of students across Louisiana. New Orleans ranked 67th among the state’s 68 districts on state accountability measures.

Then came Katrina. The school system was as damaged as the rest of the city. Buildings crumbled, and in the aftermath, teachers and students were dispersed. Louisiana essentially shut down the school district.

What followed was a real-world example of what could be possible if policymakers start public education from scratch. Working from a blank slate, Louisiana decided not to reinstitute the entrenched administrative practices of public education. Rather, it opted for a more open approach, one that provided oversight but let schools determine their own best path to success. Instead of assigning students to schools based on their neighborhood, the new system allowed parents to enroll their children in the wschool of their choice. The result? Today, about 93 percent of public school students in New Orleans go to a charter school.

For those who imagine (whether happily or unhappily) a day when charter schools dominate urban public education, the New Orleans experience is instructive. Research from Tulane University’s Douglas Harris has found that New Orleans’s charter schools are having an enormous positive effect on student achievement. Today, 62 percent of New Orleans schoolchildren score proficient or above, a figure approaching the statewide average of 68 percent.

For a generation now, charter school opponents have warned that these alternative public schools will spell doom for the American ideal of public education. It’s about time that they offer something more than anecdotes and theory to support their claims. More than two decades into the charter school experience, it’s clear that charters are not proving harmful to traditional public schools—and, if anything, are helping them do better. And the overall performance of American public education is improving, too, because a growing proportion of public schools are high-performing charters.

Photo by Rafael Infante (Courtesy of Success Academy)