America’s states and municipalities should be awash in good budget news. Unemployment remains below 5 percent, inflation is tame, and the S&P 500 rose about 20 percent in 2017—the ninth year of a bull market. Household income is pacing upward strongly again, too. Yet despite the good news, many local governments faced intense struggles last year to balance their books. Nearly a dozen states failed to pass new financial plans on time, and many with budgets in hand had to scramble midyear to cut spending.

The difficulties were nothing new, though. Localities have confronted unrelenting fiscal pressure since 2008, a result in part of the Great Recession and then the weakest recovery since World War II, but also of ever-escalating costs—including massive public-employee retirement debts—and tax collections so weak that many governments have yet to see revenues return to pre-2008 levels. Many states and localities have had to rewrite budget books, altering how they spend money in ways that leave taxpayers paying more—and receiving less.

The situation may not change for the better anytime soon. With many economists forecasting mediocre growth, and another recession inevitable at some point, states and cities may be moving into a prolonged period of austerity. “U.S. states have entered a new era characterized by chronic budget stress,” the financial analyst Gabriel Petek, a managing director in the U.S. Public Finance group at S&P Global Ratings, wrote last April in a blunt warning to taxpayers. Though states have been financially resilient for decades, Petek observed, this “long period of relative calm may have lulled some people into complacency when it comes to state finance. It shouldn’t have.”

The pressures have led local leaders to petition the federal government for more aid, but Washington, burdened by immense debt, is hardly in a position of financial strength itself. President Trump has promised $1 trillion in infrastructure spending that could provide some help to localities, but what governments across the country really need is a return to economic growth rates of 3 percent or higher, which would significantly boost tax returns. The Republican tax-reform plan, which some economists have predicted will add one percentage point or more to growth, may help, though the narrowing of the state and local tax (SALT) deduction may hurt the finances of a few high-tax states. States and cities, though, would still need to become more efficient and innovative in delivering basic services, or else face a future of tax hikes and service cuts to keep up with their mounting bills.

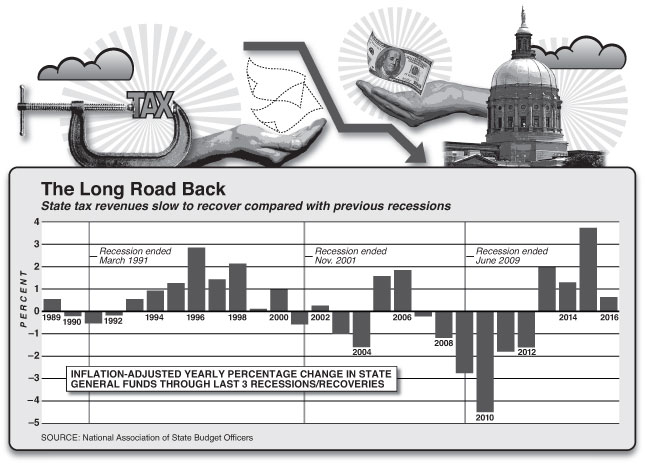

Local governments got a sense that something might be different starting in 2009, when state tax revenues, hammered by the steep recession, collapsed by nearly 9 percent—only the second time in the postwar era that state revenues had declined from one year to the next. Then revenues slumped again in 2010, by 4 percent this time, leaving governments tens of billions of dollars short of where they’d been just two years earlier. What followed was a slow recovery of tax collections; it took states until 2016 to regain everything that they had lost in the recession, on an inflation-adjusted basis. States needed only slightly more than half that time to rebound after the recessions of the early 1990s and 2001–02. While some of the currently hard-hit states are energy producers suffering from falling oil prices, even economically robust states like North and South Carolina, Arizona, Florida, and Georgia have struggled to recoup revenues, in part because of precipitous real-estate declines that have hampered their growth.

The impact of the property bust has been even worse for municipalities, which rely heavily on property taxes. According to a recent National League of Cities survey, America’s major cities still haven’t seen revenues return to pre-recessionary levels, and the forecast isn’t good. Municipalities told the NLC that the rate of growth of tax revenues began falling in 2016. Major recoveries have tended to follow past major downturns; this time, cities have barely recovered from the last recession when another could be upon them. The pressure on cities and states has been so great that in 2016, eight years into the recovery, ratings agencies downgraded the credit of 489 state and local governments.

Some of the weakness in tax receipts results from structural demographic and economic changes that local officials knew were coming but have done little to prepare for. The aging of America is raising the proportion of retirees relative to the number of workers in many states. One sign of how swiftly this is happening is the transition from wages to retirement income: worker wages went up by 18 percent in the half-decade ending in 2014 (the latest available data), while Social Security payments rose more than 50 percent and IRA distributions by more than 75 percent. Those swelling retirement monies don’t pay off for states the way a boost in worker pay does; on average, retirees have lower incomes and enjoy more tax breaks than do the employed.

Moreover, some traditional measures of prosperity, such as the unemployment rate, are misleading about the American economy’s health. Thanks to greater government incentives not to work—especially expansive disability programs—many prime working-age men have quit the labor force and thus fail to show up in unemployment statistics. Their absence from the workplace, though, means that they contribute little to state revenues.

Given such trends, states should have spent cautiously. Instead, they piled on new obligations that they likely would have had trouble financing even in a stronger recovery. Medicaid has been the biggest driver of the new spending. Last year, states spent $211 billion on Medicaid, out of $1.29 trillion in total expenditures. That sum represents a nearly 70 percent rise in spending on the program in ten years and a 220 percent increase over 20 years. Including federal dollars that flow to states, Medicaid now eats up more than a quarter of state budgets.

And more is coming. Thirty-two states expanded Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act to previously ineligible households. Though the federal government initially picked up most of the Obamacare costs, states must gradually start paying a share. The percentage is small, but states were already having trouble financing Medicaid before they extended coverage; the new costs will intensify the challenge. A 2016 Boston Globe story reflects the exasperation that many Massachusetts residents feel over the state’s seemingly perpetual Medicaid-related fiscal crisis. “Why does Massachusetts, which has been in an economic recovery for seven years, constantly careen from one state budget gap to another?” the paper asked. Blame in large part runaway health-care spending, which, the Globe notes, is “generally outpacing inflation, personal income, and tax revenue growth”—and thus “constraining the cash available for everything else, from education to support for cities and towns.” Medicaid accounts for one-third of the state budget, up from one-quarter in 2000. Originally designed as an insurance program for the poor, Medicaid now covers one-quarter of all Massachusetts residents—though the state’s poverty rate is 12 percent.

Like Massachusetts, Connecticut—one of the nation’s wealthiest states—exists in a near-perpetual condition of fiscal distress, with a budget more than 90 days late this year. (See “Connecticut on the Brink.”) Over the last decade, the Nutmeg State’s Medicaid program, including federal spending, has nearly doubled in size, to $3.7 billion, a compound annual growth rate of more than 7 percent; the state’s general-fund revenues have expanded by just 1.7 percent annually in that time. With a poverty rate under 10 percent, Connecticut enrolls more than one-fifth of its residents in Medicaid.

“Including federal dollars that flow to states, Medicaid now eats up more than a quarter of state budgets.”

Exploding Medicaid costs are being felt in many other states. In its early days in the mid-1970s, Nevada’s Medicaid program covered about 23,000 poor residents. Today, 638,000 Nevadans get insurance through the program; officials had underestimated by more than 130,000 the number of residents who would apply for the subsidy once the state expanded it under the Affordable Care Act. Medicaid costs twice as much in Nevada as it did ten years ago, and the state’s contribution of tax dollars has swollen by more than two-thirds over that time period. Meantime, in Wisconsin—a state that didn’t expand Medicaid—costs are still spiraling upward. Overall state spending on most items was basically flat in 2016, but Medicaid surged more than 7 percent, soaking up most of the state’s new revenues. Medicaid now consumes 18 percent of Wisconsin’s budget, up from 10 percent in 2011. “When municipalities and school districts grouse about not getting a bigger share of the state budget, truth is there aren’t a lot of discretionary dollars lying around the state treasury,” one Wisconsin newspaper editorialized.

While many states have funded Medicaid expansion by reducing other spending, the burgeoning health bill is also behind states’ largest recent tax hikes. Earlier this year, Oregon passed a $550 million health-care tax package that levies fees on hospitals and on premiums for private health insurance. Why did a state with strong job growth, a healthy housing market, and strong wage growth need a fat tax increase? Because Oregon—total population, just 4.1 million—now has 1 million people receiving Medicaid. Lawmakers had to grapple with a two-year projected deficit of more than $1.5 billion, spurred by the bloating cost of the program—up 75 percent in ten years and likely to grow even faster in the coming years, thanks to 300,000-plus new enrollees under Obamacare. Hard-pressed Connecticut has taken a similar road. In 2012, the state instituted a tax on hospitals to help fund Medicaid. This year, the tax will generate about $550 million, up from $349 million in revenues in 2012, but as the take has grown, so has the perception that the high cost is hurting the local industry. “The hospital tax has increased costs for patients, caused the loss of thousands of health-care jobs, extended wait times, and reduced access to care for those who need it most,” said the CEO of the Connecticut Hospital Association last year.

An immense pension crisis also looms over local governments. States and municipalities have amassed at least $1.5 trillion in this debt—equal to what states collect in taxes in one year—though some estimates put the real cost at three times that much. Though governments have about 15 years before much of this debt comes due, most states and localities struggle to put enough money aside yearly to stop the debt from climbing, much less reduce it. A recent Bloomberg study found that, from 2014 through 2016, only six states managed to reduce pension debt, despite the national economic expansion. On average, state pension systems were less than 72 percent funded at the close of 2016; before the market crash of 2008, they were 86 percent funded. The stock market’s surge after Donald Trump’s November 2016 election will raise funding levels a few more points, but that a nine-year bull market hasn’t sufficed to return pension systems to pre-2008 funding levels, much less back to the full funding that many enjoyed at the end of the 1990s, is worrisome.

Over the past decade, local governments have contributed an extra $290 billion to pension systems to help contain the debt increase, according to U.S. Census figures. That’s money that governments could have spent on roads and bridges, schools, economic development, or in cutting taxes. While places with the most glaring problems—Illinois, Kentucky, Connecticut, Chicago, Houston, Dallas, Los Angeles—have received attention, the crisis is widespread. Nearly two dozen states have less than 70 percent of the money they need to fulfill their obligations, and a dozen are less than 60 percent funded, including Massachusetts, Colorado, Maryland, Minnesota, South Carolina, New Hampshire, and Louisiana. The Financial Accounting Standards Board, which sets policy for private-sector pensions, defines the status of a system less than 80 percent funded as “critical.”

Governments are struggling to make the necessary payments. In a September meeting with CalPERS, the giant California public pension fund, representatives from a dozen California localities complained that dramatically rising pension costs—projected to triple for some cities and school districts—will lead to a “gradual strangulation” of public services. “In three to four years our cash flow is going to be gone,” the finance director of Oroville testified. “We don’t even know how we are going to operate past four years. We have been saying the bankruptcy word, which is not very popular.” Sharp increases in contributions demanded by CalSTRS, the state’s teacher-retirement fund, are similarly squeezing school districts. The Santa Barbara Unified School District’s bill will mount from $10 million in the 2015 school year to $20 million in seven years. The giant Los Angeles Unified School District’s annual pension payments, $190 million in 2010, soared to $371 million in 2015 and will hit approximately $594 million in 2018. At that point, the district faces a projected deficit of some $400 million—and it will have to sustain that enhanced spending level for decades.

The budget crunch is already choking essential services. Josh McGee’s 2016 Manhattan Institute study found that rising pension contributions—which have tripled at school districts around the country since 2000—have been accompanied by underinvestment in school facilities and instructional materials. Per-pupil spending on equipment and property fell 26 percent between 2000 and 2013, “likely resulting in a growing backlog of expensive repairs and replacements that will need to be made sometime down the road,” McGee noted. A 2013 report by three education groups estimated a backlog of $271 million in deferred maintenance at school districts. Meantime, spending on textbooks and other instructional supplies per pupil has fallen by 10 percent since 2000.

As pension systems soak up more public dollars, cities and states are raising taxes to replace the diverted funds. To fund its hugely indebted pension system for city workers, Chicago hiked property taxes by $588 million in 2015; the school system then increased the portion of the city’s property tax devoted to schools by another $250 million because of the school system’s own financial problems. And much more will be needed. Even with the tax increase, the pension system commands nearly 60 percent of all property revenues that the city collects. If Chicago is to make progress on shrinking its pension debt, it will need to contribute $2.2 billion annually to fund pensions by 2022—twice the city’s current total property-tax take.

Sometimes it’s not even apparent that pensions are behind the levies. Seattle wants to raise taxes by $130 million annually, saying that it needs the money to finance a spate of new programs, including subsidized housing. The city is short of funds for the new initiatives, though its technology-driven economy is thriving and generating lots of revenues. The reason: Seattle has one of the worst-funded pension systems among major cities in the country; over the next decade, it will pour more than $800 million in extra funds into the system, just to deal with the debt. New Jersey just committed to putting $1 billion from its lottery system into pensions, but that money was previously funding other programs, including state universities—so Jersey will have to slash spending for them, or find new revenues. Pensions also are gobbling funds in states where taxes are bouncing back. Georgia projects $700 million in additional tax collections this year, but some $400 million of the money will go to pay off rising retirement costs.

Pensions are part of a larger local-government debt problem, which includes other promised worker-retirement benefits (such as subsidized health care) and municipal borrowing used to finance building projects. Since 2009, the total cost of supporting these legacy costs has risen from 16.7 percent of municipal budgets to 19.1 percent, according to data by Richard Ciccarone of Merritt Research Services. For many large cities, the actual burden is heavier still, taking more than $4 of every $10 in Milwaukee’s budget and $3 of every $10 in San Jose’s and Jacksonville’s. Cities such as Portland, Chicago, Houston, Dallas, and New York are all spending about one-quarter of their budgets on legacy costs.

The added burden couldn’t come at a worse time for cities, with states pushing their own financial woes down to their municipalities in the form of significantly curtailed local aid. State aid to counties, cities, towns, and school districts averaged an annual growth rate of just 1.1 percent from 2009 to 2015—a major comedown from the 4.1 percent average growth rate that had previously prevailed. The new math just doesn’t work for many local governments: their costs keep rising, even as state aid slows. For instance, state aid to public schools grew by about $26 billion from 2009 through 2015—but the cost of employee benefits alone at the nation’s public schools surged by $20 billion over that same period.

Municipalities and school districts have resorted to tax increases and service cuts to try to keep up with the costs. In Pennsylvania, reductions in state money for school transportation and other programs prompted about three-quarters of surveyed school districts to say that they planned to raise property taxes, and about half to say that they would cut staff. The schools have been buffeted by retirement costs, rising by as much as 10 percent annually in some districts. Connecticut’s legislature optimistically passed a budget two years ago that would supposedly provide communities with nearly $700 million in additional aid in 2017 and 2018. But facing slow revenue growth, Governor Dannel Malloy proposed axing hundreds of millions of dollars in municipal aid, and sought to force localities to shoulder one-third of the anticipated $1 billion that Hartford must contribute to shore up the state’s teacher-pension fund. Legislators from both parties balked, part of the reason that Connecticut’s recent budget battle lasted more than three months beyond the deadline for a new fiscal plan. The impasse cost municipalities and school districts tens of millions of dollars in lost aid.

Municipalities and school districts have sued states over funding. Districts in New Mexico and Kansas launched a suit claiming that state aid fell short of what courts have mandated. Arizona schools have also sued, contending that the fast-growing state isn’t living up to its obligation to build new schools. Things got so rancorous in Michigan that the legislature passed a measure punishing districts that use state grants to help finance lawsuits against the state.

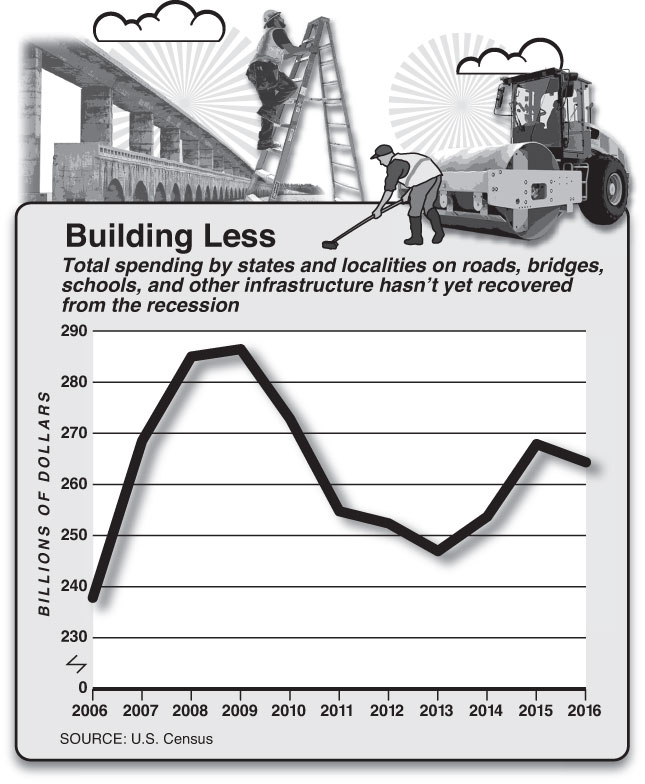

Local governments have also cut investments in the once-basic category of infrastructure. Adjusted for inflation, construction spending on infrastructure is down by $47 billion, or 18 percent, since 2009, with schools, water-supply systems, and sewage facilities showing the biggest reductions. The average age of city-government-owned properties, plants, and equipment has gone from 12 years in 2008 to 15.6 years in 2016, as new investment gets put off, according to Merritt Research. Virtually every category of public infrastructure has aged, from highways to hospitals to power plants to airports. “As states look to allocate their resources among growing health care and education needs, they cannot devote as much to transportation infrastructure as they might want,” the ratings firm Moody’s observed in January 2017. And even though more than half of all states have raised gas taxes, typically used to finance public infrastructure, Moody’s predicts that localities will continue to borrow heavily in coming years to fund such infrastructure, ballooning transportation-related government debt.

How can states and localities escape chronic budget stress and a self-defeating cycle of service cuts and new taxes? Higher economic growth rates would obviously help, but localities really need to transform the way they do business.

Seizing control of Medicaid spending is perhaps the Number One task. Though efforts to repeal or modify the Affordable Care Act have thus far failed because some congressional Republicans worry about the impact on state budgets, the numbers are inexorable: allowing Medicaid spending to keep escalating at its current rate will utterly drain state and federal budgets. A far better alternative is to pare Medicaid back to its origins as a program for the poor, and let each state experiment with private insurance innovations to cover many of those recently put on Medicaid but who aren’t destitute. The solution would also entail ending Obama- care-mandated high-cost, low-deductible insurance plans, which force insurers to pay for many services at prices that discourage people from purchasing private insurance. Instead, the federal government should allow states to experiment with low-cost, high-deductible plans that protect patients from catastrophic costs—the kinds of plans that many states were exploring before Obamacare eradicated them. Moderate-income households buying this insurance could get government-subsidized health-savings accounts to pay for regular medical expenses. This would put health care back in the hands of such patients, rather than making government the gateway to health care for a quarter of all non-retired Americans.

“States must stop the bleeding by switching to some form of defined-contribution or hybrid pensions, to cut costs.”

Grappling with pension debt is also essential. Since 2009, virtually every state has claimed to make some kind of reform to its pension system, but the basic math of most defined-benefit retirement systems still doesn’t work because the actual cost of providing the benefits promised is far higher than experts previously estimated. As most pension systems keep accumulating debt, states must stop the bleeding by switching to some form of defined-contribution or hybrid pensions, which reduce expenditures and don’t expose taxpayers to unlimited long-term debts. Rhode Island, which created just such a system, offering a basic, affordable monthly pension benefit combined with a 401(k)-style retirement savings account, has shown the way. Other options are to reduce benefits that aren’t typically considered part of the basic pension contract, such as expensive annual cost-of-living adjustments. In some states, including California and Illinois, local laws or court rulings limit the changes that can be made to current worker pensions—making it vital to institute less expensive and risky pension programs for new workers. Most such states have yet to do so, however.

Local governments also need to do more than rely on debt and higher taxes to boost their infrastructure efforts. In a more technologically sophisticated environment, local governments should focus on a private-enterprise model for financing transportation through user fees, which ultimately direct responsibility for paying for new projects—whether toll roads, airports, or bridges—to those who will use the facilities, rather than forcing everyone to pay through general taxes. Around the world, portfolio managers are directing vast sums into such investments because they know that users can pay for these investments through innovations like electronic-toll collection. Up to now, Europe and other developed areas have welcomed that money far more than has the United States.

One of the few great inescapable facts in the field of economics is the reality of the business cycle,” Moody’s recently observed. “No matter how high-flying an economy might appear, another recession is coming sooner or later.” But states and cities haven’t been this unprepared in decades for the next economic slowdown. Even a mild recession may turn out to be more painful than politicians and voters anticipate. The only way to prepare is to face up to the fact that public-sector budget math has changed—and that governments have to change with it.

Top Illustration by The Heads of State