Bill de Blasio’s 2013 mayoral victory unsettled New York’s urban reformers. Over the course of five mayoral terms, Rudolph Giuliani and Michael Bloomberg had shown the Big Apple that crime and welfare could be dramatically reduced, education improved, and economic opportunities for people of all races and backgrounds enhanced. De Blasio’s win, despite his open repudiation of the Giuliani-Bloomberg legacy, raised a disturbing question: Were New Yorkers turning their backs on the policies that had brought the city back from decline?

So far, though de Blasio has made many high-profile symbolic moves to the left, New York remains healthy. Crime, despite a much-publicized spike in murders in 2015, is at near-record lows. Welfare rolls are up by about 8 percent, which is troubling, but they’re still well below historical highs. And the city’s economy keeps chugging along, employing a record number of people and adding jobs at roughly the national average. Reformers could take solace in this and tell themselves that the city’s politics are essentially unchanged.

A close look at electoral and demographic data, however, shows that the tenuous political constituency that backed Giuliani and Bloomberg at key moments has dissolved. The political path that reformers used in the 1990s and 2000s—elect a strong mayor on the Republican line with backing from dissident Democrats and Independents—is no longer a reliable option. New Yorkers who wish to protect and expand the Giuliani- and Bloomberg-era innovations must experiment with other political tools if they want to ensure that the city does not slide back into decay, disorder, and decline.

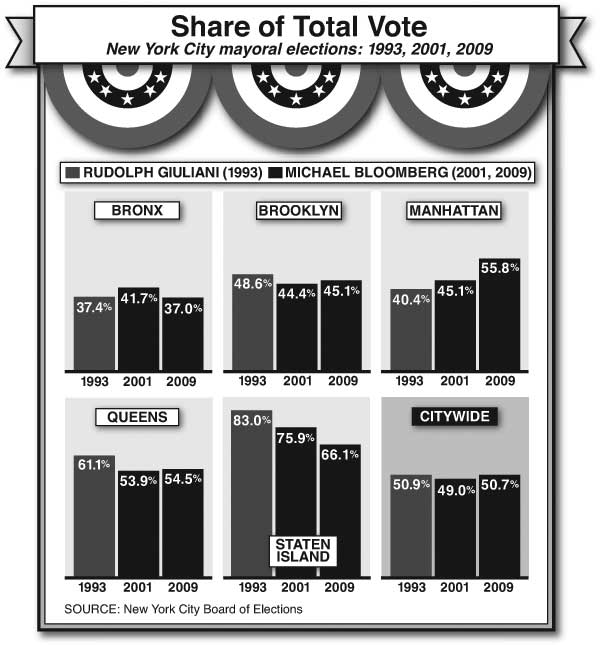

As the chart on page 42 shows, Giuliani and Bloomberg relied on winning large majorities in ethnic white communities in Queens and Staten Island, areas that were both the bastions of the Republican Party’s strength in the city and where the white, working-class “Reagan Democrats” lived. Elsewhere, Giuliani and Bloomberg ran even in Brooklyn to offset losses among nonwhite and upscale liberal whites in the Bronx and Manhattan. Both men received nearly identical shares of the citywide vote in their initial, close victories, while winning similar shares of the vote in each of the five boroughs.

Unfortunately, the kinds of voters Giuliani and Bloomberg relied on have strikingly declined in number since the early 1990s. Census data compiled by New York University’s Furman Center show that non-Hispanic whites constituted 43 percent of the city’s population in 1990 but only 33 percent in 2010. The decline was even more precipitous in the two boroughs that formed the Giuliani-Bloomberg coalition’s base. In 1990, 85 percent of Staten Islanders and 48 percent of Queens residents were non-Hispanic white. By 2010, non-Hispanic whites made up only 73 percent of Staten Island’s and 28 percent of Queens’s residents. Their nonwhite replacements, largely Hispanic and Asian, are much likelier to back Democrats, regardless of the circumstances.

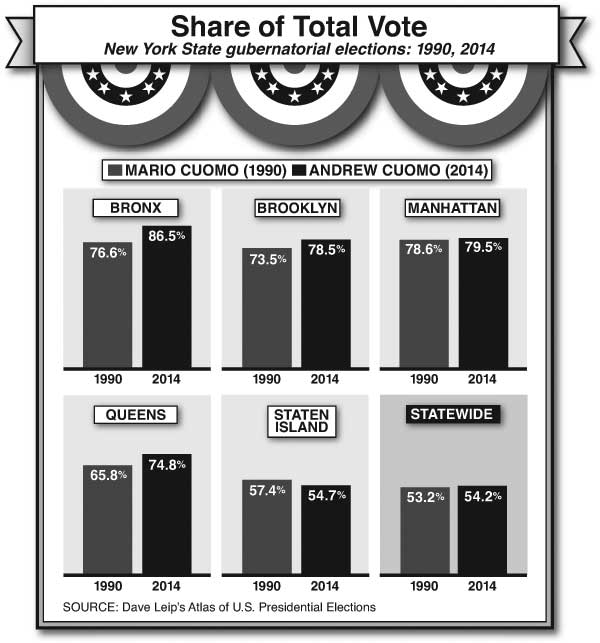

One can see the effect of these changes on the city’s partisan proclivities by comparing the gubernatorial-election results of the two Cuomos: Mario and Andrew. Both father and son had relatively easy reelection campaigns at the bookends of the era we’re examining, 1990 and 2014. Both won nearly identical shares of the vote at the statewide level: Mario got 54.3 percent in 1990, and Andrew garnered 53.2 percent in 2014. Yet their shares of the vote in New York City differed in important ways. The chart on page 43 shows how Andrew Cuomo received significantly higher shares of the vote in four of the city’s five boroughs than his father did two decades earlier—and this with a Green Party candidate siphoning between 2 percent and 7 percent of the vote away from him. (Mario Cuomo faced no significant left-wing opposition in his 1990 race.) The conclusion is clear: New York City’s underlying demographic changes have turned an already-liberal city sharply left.

These changes don’t simply apply to partisan races where city issues are irrelevant. Their effect was already apparent in Mayor Bloomberg’s surprisingly close 2009 reelection. While he won nearly the same share of the citywide vote (50.7 percent) that he received in 2001 (50.3 percent), the distribution among the boroughs was very different. Bloomberg’s vote share dropped in four of the five boroughs, including an 11-point drop in Staten Island. He won reelection only because he carried Manhattan, with 55.8 percent of the vote—much more than the 50.9 percent that Giuliani got on the island in his landslide 1997 reelection.

Gotham’s demographics have continued to change since 2009. The Census Bureau estimates that New York’s population has increased by 375,000 people since the census of April 2010. More than 452,000 people have emigrated from foreign countries to the city since then, while more than 400,000 people left New York to live elsewhere. No accurate estimates of the city’s racial and ethnic composition currently exist, but these data suggest that the decline in the white percentage of the population and, with it, New York’s drift to the Democrats continue apace.

These data also show that determined reformers need to find new ways of influencing politics and building coalitions. They have several options from which to choose.

The first might be called the “Club for Growth” approach. The Club for Growth is an advocacy group that contributes to the campaigns of fiscally conservative candidates for national offices, including in the House and Senate. The Club has been most active in Republican Party primary elections, but a New York version would take the city’s partisan leanings as a given and seek to build reform constituencies within the Democratic Party. Like the national Club for Growth, the New York Club would focus its efforts on primary elections. It would target non-mayoral races—including those for borough president, city council, and other citywide electoral offices—and seek to elect promising candidates.

Such an effort could work only if the leaders and campaign staff are themselves active Democrats. People like Eva Moskowitz, Ray Kelly, and Joel Klein—all Democrats but not de Blasio–style progressives—come to mind. All are civic leaders in important reform efforts that Republicans and Independents can also support. They and others like them could form an urban version of the Democratic Leadership Council of the 1980s and 1990s, which organized moderate and center-left Democrats to take back their party from the Left. A New York Club for Growth would have the same goal and presumably attract similar supporters.

Wealthy Republicans and Independents could contribute to this effort, but most of the support must come from those perceived to be loyal Democrats. Any effort by non-Democrats to tip the outcome of Democratic primaries would be viewed as a hostile takeover and hence be less likely to succeed. The New York Club would also need a clearly defined statement of principles and an agenda. The national Club offers a clear philosophy and uses a rigorous screening process to assess prospective candidates on key issues. Donors and candidates know exactly what they’re signing on to.

The necessarily partisan focus of a New York Club for Growth might discourage many participants. New York’s election laws, however, provide an almost unique way for individuals to influence elections: third-party cross-endorsement. New Yorkers have used this approach for decades to pressure Democrats and Republicans to select nominees amenable to the third party.

New York is one of only two states that permit a party to endorse a candidate running on another party line and place the candidate’s name on its own ballot line, as well. This gives these smaller parties power: if one of the major parties wants its voters’ support, that party must nominate a candidate amenable to those voters’ views. This, in turn, gives the major parties the ability to broaden their appeal without watering down their core views. Liberal Party members who would never vote Republican, for example, voted, on the Liberal Party line, for Republican mayoral candidates in many twentieth-century elections.

A Republican has never been elected in New York City without the cross-endorsement of an important third party. Fiorello La Guardia enjoyed crucial support from the American Labor Party, while the Liberals provided the needed cross-endorsement for John Lindsay and Rudolph Giuliani. Even Michael Bloomberg required the cross-endorsement of the Independence Party to gain enough votes to outpoll his Democratic rivals. The fact that de Blasio’s 2013 opponent, Joe Lhota, received the cross-endorsement only of the small Conservative Party was an early signal that he would fall well short of winning.

Those considering the third-party option must decide whether it is easier to start a new party or work within an existing one. Starting a new party is daunting; state law only grants a party automatic ballot status if its gubernatorial candidate wins 50,000 votes. Reformers who wish to use the third-party approach would probably meet with more success by building support within a third party that already has ballot status. They could then endorse suitable gubernatorial candidates, ensuring their spot on city ballots, and focus on using cross-endorsement to influence candidates for city office.

The party likeliest to be open to such cooperation is the conveniently named New York Reform Party. Formed by 2014 Republican gubernatorial candidate Rob Astorino as the Stop Common Core Party, the Reform Party has qualified for ballot status through 2018 because Astorino received the required 50,000 votes on its party line. Yet the Reform Party currently has almost no registered members. Only 900 people in the entire state—and only 138 in the city—were registered as of November 1, making Reform easily the smallest party in the state. Even the party that Governor Andrew Cuomo created for his 2014 reelection, the Women’s Equality Party, has nearly 2,300 statewide registrants.

An expanded Reform Party could operate like the union-backed Working Families Party does—using the resources at its disposal to encourage major-party candidates to seek its endorsement or risk losing votes to its own candidate. In most areas of the city, an active Reform Party could become the dominant source of opposition to city hall, going to the tiny Republican Party for its cross-endorsement, rather than vice versa. An active Reform Party could also be the best vehicle to build a political constituency among New York’s new nonwhite voters, who might find the national Republican brand off-putting and prefer a less ideological brand of politics at the local level.

While potentially more effective than a New York City Club for Growth, the Reform Party option has its own downsides. Helping to run and maintain a political party, even a small one, demands lots of work and commitment, as well as a ground presence that enrolls and organizes voters. The Working Families Party uses its constituent unions to provide the manpower and the organizing muscle, while the New York Conservative Party relies on its status as the only party firmly committed to pro-life and social conservative causes to recruit members. Unlike the Club approach, the Reform Party option requires more than a few well-heeled citizens and an effective campaign staff: it calls for sustained, passionate citizen involvement.

One can envision the charter school movement providing some of the necessary backing and manpower. Charter schools are always under assault from progressives and unions, and charter school parents and advocates currently rely on lobbying officeholders to maintain support. Combining in a third party could strengthen their hand politically and give them a regular voice in city affairs. More than 95,000 children currently attend charter schools, and that number has grown by an average of 10,000 per year for each of the last four years. There could be enough politically interested parents and activists to form the backbone of a third party committed to expanding educational choice.

Police officers—if not their union—could also provide crucial support. De Blasio’s tenure should show cops that their honored place in New York’s civic life—and the job perks that go along with it—is not secure. Using the Reform Party as their vehicle would give the police leverage with any mayor. Citizens involved with the Police Foundation could offer additional manpower and financial backing.

Small-business people represent yet another possible constituency. They presumably pursue their interests via their elected council members, but a vibrant, pro-small-business Reform Party would give them political clout in every district in the city. Since many small-business people are also recent immigrants, especially Chinese and Koreans, focusing a party on their concerns would help address the city’s demographic changes, incorporating newly arrived New Yorkers into a civic-minded philosophy.

A serious organizational effort would likely succeed in taking over the Reform Party. Indeed, Curtis Sliwa, founder of the Guardian Angels and talk-radio host, has already mounted a takeover challenge that party founder Astorino is challenging in court. Given the party’s minuscule size, however, a second, more serious, challenge would easily swamp any resistance from Sliwa or Astorino—assuming that they’re not included in the new, potentially much more significant, organization.

Some Giuliani-era supporters might wonder why a revitalized Republican Party couldn’t play a leading role in these efforts. Theoretically, it could, of course, but the city’s GOP has become primarily a platform for local leaders to cut deals. They would likely resist efforts to make the party more open and issue-driven, so any such battle would be an uphill one. And, like it or not, national partisan identity has a role in civic politics. Many reformers are national Democrats and find committing to a new Republican Party unacceptable for reasons that extend far beyond New York City—especially with Republican Donald Trump assuming the presidency.

Another option exists: changing the city’s elections from a partisan to a nonpartisan system. Nonpartisan elections for local office are the norm in more than 80 percent of American cities, according to Randy Mastro, former deputy mayor under Rudy Giuliani. Twenty-three of the 30 largest U.S. cities elect their mayors via a nonpartisan system. Partisan identification is perhaps the strongest weapon in the progressive arsenal: many Democrats simply won’t vote for a Republican, making the Democratic Party primary—where progressives have more impact—the effective general election. Remove the partisan barriers, however, and voters could focus more on the candidates and less on their affiliations. This would probably help reform-oriented candidates.

Advocates for nonpartisan elections will need to garner more support than Mayor Bloomberg did when he attempted to push this change through in 2003. Despite spending millions of dollars of his own money, Bloomberg couldn’t convince New Yorkers, who rejected the proposed change by a 71 to 29 margin. A close examination of the results, though, shows that partisanship was an important predictor of opposition. Queens and Staten Island voted against the proposal by significantly lower margins than did the other three boroughs. Moreover, within each borough, a “yes” vote for nonpartisan elections tracked closely with opposition in the prior year to the Democratic nominee for governor, Carl McCall. The worse McCall did, the higher the support for nonpartisan elections. This strongly suggests that even Bloomberg-supporting Democrats and Independents perceived the measure as a Republican power play. When push came to shove, these voters, crucial to the Giuliani-Bloomberg coalition, backed their party over their mayor.

Any attempt to reintroduce nonpartisan elections must overcome this obstacle. A significant faction of Democrats would need to conclude that their interests are better served by reducing the power that progressives hold within the party-primary system and endorsing a new election framework that allows them to join with Republicans in an informal coalition.

Similar considerations led Chicago to abandon its partisan mayoral-election system in 1995. The victory of progressive African-American Harold Washington in the 1983 and 1987 Democratic primaries meant that more moderate Democratic officeholders found themselves shut out of the mayoralty. Richard M. Daley, who eventually became mayor after Washington’s untimely death in office, backed changing the system in 1986 precisely to end the potential lock that Washington’s faction would otherwise have on the mayor’s office. No candidate backed primarily by progressive elements has won Chicago’s mayoralty since the change; nor has any significant Republican even run for the office. Both Daley and current mayor Rahm Emanuel were therefore able to count on support from the city’s small Republican base and fend off opponents from their left. This GOP support was essential to Emanuel’s 2015 reelection in the face of an aggressive challenge from progressive Democrat Jesus “Chuy” Garcia. A nonpartisan mayoral-election system won’t guarantee that a reform-minded mayor would win, but it would presumably increase his or her chances.

One might take issue with this argument by pointing out that Chicago, which hasn’t elected a Republican mayor since 1927, is a mess, while New York voted for five consecutive Republican mayoral terms in the 1990s and 2000s and saw substantial positive change as a result. Yet with the accelerating demographic shifts in the city, it seems more probable that reform efforts will come in the future from centrist Democrats, who might find nonpartisan elections just the vehicle they need.

Any of the foregoing proposals requires significant ongoing effort and political cooperation. Reformers might find it easier to create temporary coalitions around specific issues. In these cases, they should consider aggressive use of voter-sponsored initiatives to amend the city charter.

Voters last exercised this power in 1993 to impose term limits on the mayor and city council. The process itself is complicated; but essentially, an initiative endorsed by 45,000 registered voters can be placed on the ballot for approval. Any initiative receiving a majority of votes then becomes part of the city’s charter, and its provisions have the effect of law.

This method of political influence avoids some of the problems inherent in the other approaches. Reform groups need not settle on a common, comprehensive platform, as would be required to launch a third party or to follow the Club for Growth model, nor would they have to put aside partisan interests, as would be necessary to change the municipal-election system. They need only agree on a single, specific proposal and go their separate ways after the measure wins or loses.

Voters from left and right have taken this route to influence government policy in cities around the country. Conservatives have used voter initiatives, for example, to enact tax and spending limitations or crime-control measures. Liberal groups have used them to pass targeted tax hikes for spending programs or to ensure specific funding levels for public schools.

“Reformers who close their eyes to the city’s new political and demographic realities won’t have much success.”

Under current state law, New Yorkers can put this tool to use only for matters deemed to be of local concern. Courts have kept some voter initiatives off the ballot on grounds that such proposals covered matters of state, not local, interest. This limitation kept two measures seeking to reduce class sizes in city schools off the ballot in 2003 and 2005. Advocates for specific reforms, therefore, can’t be certain in advance that their measure will be permitted to go forward for a vote.

The looming vote on a statewide constitutional convention could offer a way to circumvent this barrier. The state constitution requires that a vote be held every 20 years to evaluate the need for a constitutional convention. The vote will occur this year. City reformers could push for a convention and, if one takes place, use the process to revamp the constitution to expand the role of voter initiatives and referenda. This would offer greater leeway to protect and extend effective policies on a case-by-case basis.

Reformers might also propose structural changes that would reduce mayoral power. These could include, say, making police commissioner an elected position, thus removing policing policy from the mayor and placing it effectively with the people. This would not be an untested innovation: 98 percent of the nation’s county-level sheriffs are elected, and police commissioners are elected directly in England and Wales. Should a majority of New Yorkers want a tougher crime policy than the mayor does, moving to an elective arrangement could prove effective in maintaining Giuliani-Bloomberg-style policing. Recall initiatives, in which citizens can remove officeholders before their terms expire, offer another option. A recall would let a majority of voters overcome partisan divisions to issue a strong negative verdict when a mayor strays too far from widely shared values.

New Yorkers who love their city have every reason to be worried. While Mayor de Blasio has so far respected many of the policies that turned the city around, his rhetoric and history indicate that he is an ardent foe of the vision of government pursued by Mayors Giuliani and Bloomberg. One can read too much into de Blasio’s 2013 victory. As with all elections, personality, tactics, and circumstances mattered. De Blasio’s clever campaign ads had as much to do with his primary win as any voter endorsement of his broader progressive philosophy. Yet it’s also possible to read too little into that win. The city’s demographics have changed a lot, weakening the political coalition that elected Giuliani and Bloomberg. Politics remains the art of the possible, but it requires art and skill to discern what is possible and how to achieve it at any given time. Reformers who close their eyes to the city’s new political and demographic realities won’t have much success. Bold new approaches, combined with an appreciation for the values of the city’s new residents, would give reformers a fighting chance. All those who love the vibrant, innovative, cultured place we call New York should eagerly join the fight.

Photo: Rudolph Giuliani and Michael Bloomberg defeated Democratic opponents for mayor in five consecutive elections with backing from important third parties. (RICHARD B. LEVINE/NEWSCOM)