Through a Different Lens: Stanley Kubrick’s Photographs, Museum of the City of New York, through October 28

The Museum of the City of New York on Fifth Avenue does serious, inventive work at the intersection of art and history. Its new show, Through a Different Lens: Stanley Kubrick’s Photographs is a must-see example. Starting at 17, Kubrick (1928-1999) worked for Look magazine for five years as a staff photographer in the years immediately after World War II. After 129 assignments and 12,000 photographs, he started making films. This pivotal experience propelled him to a career directing Spartacus, Dr. Strangelove, 2001: A Space Odyssey, A Clockwork Orange, and other great, break-the-mold films.

The show’s curators have taken an artist about whom so much has been written—Kubrick is a cult figure and endlessly dissected—and given us something new. And what’s new about Kubrick takes us to his earliest days when his camera changed from a toy to a tool, and photography for him went from a game to a calling. The exhibition is chronological and shows the development from Kubrick the kid, clearly guided and a rote recorder, to Kubrick at only 22, the conceptualizer and risk-taker. The museum did something similar last year with its great Todd Webb show, when it took a little-known photographer, also living in New York in the 1940s, and presented work fresh to many of us.

The visitor to Through a Different Lens could join me on one of my favorite chases: find among the juvenalia the seeds of genius. Or, enjoy the photographs as the treats they are. On view is the work of an engaging, entrepreneurial, and brilliant high school senior from the Bronx let loose with a camera on America’s biggest and most dynamic city, just shaken from a laser-like focus on war and, before that, the stupor of the Great Depression.

Kubrick wasn’t the first photographer to find raw material on the subway, but he was certainly among the most dogged. He spent hundreds of hours underground, many of them from midnight to dawn, when riders were most bedraggled and most unguarded. He was then and always a perfectionist. This relentless chaser of the right moment would take hundreds of shots, often sequenced and close to moviemaking, to get what he wanted. He experimented with exposure times and cameras to overcome the triple challenges of subway photography: moving cars, bad lighting, and his target subjects getting off the train. He learned that perfectionism takes patience and persistence. It’s painful for the subject but for the taskmaster, too. For Kubrick, even then it was hard to tell the difference between discipline and obsession.

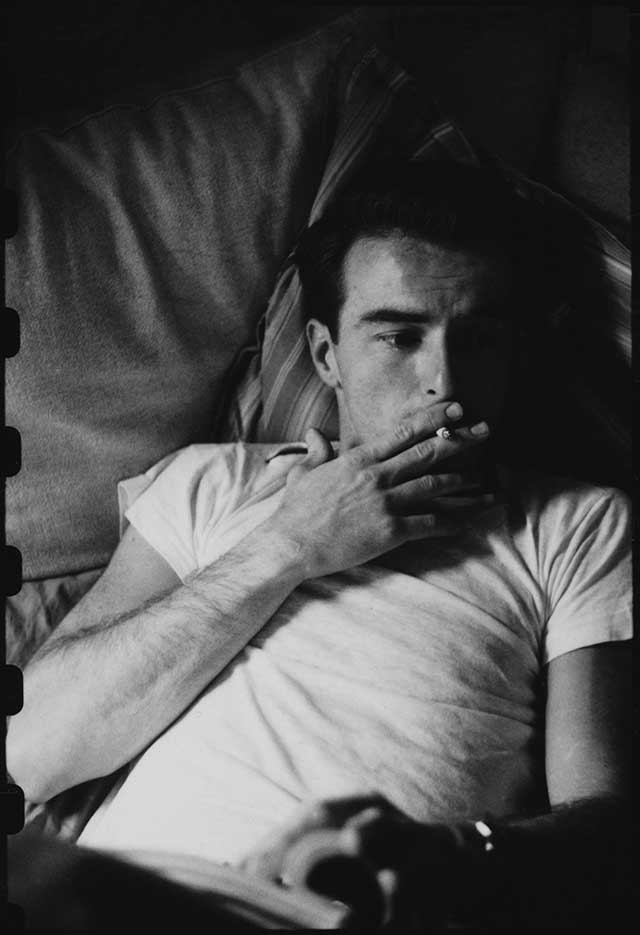

It’s safe to say that in these early years he mastered the elements of photography. He was paid a pittance, supervised lightly, and cultivated by grizzled old-timers at Look who knew a prodigy when they saw one. An informal “Bringing Up Stanley Club” steered advice and juicy assignments his way. As time passed, he developed his own storylines. His handlers sent him to photograph celebrities: the already famous, like Frank Sinatra, and emerging stars like Montgomery Clift. He learned how to deal with them and catch with the camera what made them irresistible.

Kubrick had an eye for incongruity. It’s hard to fathom an odder couple than Dwight Eisenhower and Columbia University, yet in 1948 Europe’s liberator sought to crack a very different brand of nuts from the Nazis in accepting the school’s presidency. Kubrick did a sequence of photographs of life on campus during Ike’s early days. He was the same age as the students but never went to college. He fastened on a world as different from his own as it was from Ike’s, finding a photogenic otherness in its rituals.

Kubrick used infrared film and flash, which was rare among magazine photographers. It opened the door to vignettes where furtive behavior lent itself to unusual poses and mood-making contrasts of light and dark. The street photographer Weegee was already using these techniques to catch people unaware and primal. Weegee’s photography book, Naked City, appeared in 1945. Jules Dassin’s 1948 film, The Naked City, also set in New York, pioneered on-location shooting and became a commercial hit. Kubrick’s early aesthetic had a peer, if not an inspiration, in film noir’s gritty, “you are there” feel. The best postwar Italian movies, like Open City and The Bicycle Thief, had big American audiences, too. Kubrick saw hundreds of movies during his time as Look’s roving reporter. For him, inspirations fortified one another and stimulated his creativity.

Kubrick developed enormously as an artist in the years following his beat with Look, so seeking a direct trail from his teenage years to films like his last, the darkly sinister Eyes Wide Shut, is likely to produce lots of false leads and dead ends. Kubrick surely learned the ins and outs of tracking shots from his magazine work, whether tailing Ike or, more memorably, a shoeshine boy named Mickey. He always used tracking shots in his films. After all, the computer Hal is cinema’s most novel and assiduous stalker and snoop. Aside from his nighttime use of flash, Kubrick the film director usually preferred source lighting—the lighting of necessity for street photographers. Kubrick was no Norman Rockwell; he never did wholesome or winsome. His Look photographs and his best movies give pride of place to the most freakish among us.

You don’t learn courage; you have it or you don’t. You can, though, learn how to make instinct a powerful tool. As a teen, and a precocious one, Kubrick learned he could go places that no one else could. That, along with his smarts and all-seeing eye, and a big dollop of Bronx-style chutzpah, launched him like a rocket.

Top Photo: Self-Portrait / Images courtesy of the Museum of the City of New York.