We Have Never Been Woke: The Cultural Contradictions of a New Elite, by Musa al-Gharbi (Princeton, 432 pp., $35)

What is a theory? In philosophy, we usually think of it as a set of propositions. These propositions might be challenged directly, or they might turn out to generate empirical predictions or logical consequences that could be challenged instead. But we can also think of theories as things that live in people’s minds—ideas that shape our vocabularies, our maps of the world, our attunements to perceptions, our instincts about what jumps out as important in our environments. Thinking this way, a theory’s measure is its number of adherents. What ought to be evaluated is how they think when gripped by the theory, not what the theory’s abstract implications might be.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

Theories of politics in particular seem apt for this sort of evaluation. Some political philosophies do not specifically entail that horrible things ought to be done. But if such a theory’s adherents always seem to do horrible things once they get power, that should count against the theory.

Musa al-Gharbi’s book We Have Never Been Woke presents an account of the character and causes of woke politics. It fills a gap in this regard: al-Gharbi, primarily a sociologist, gives a different kind of perspective than, say, Yascha Mounk’s relatively centrist history of wokeness as rooted in radical academic ideas or Richard Hanania’s relatively right-wing history of wokeness as rooted in activist jurisprudence and the administrative state. But at a further remove, We Have Never Been Woke is a story of how theories—both the woke theories criticized and the more classically leftist theories used to criticize them—simultaneously open our eyes to some things while blinding us to others.

The details that stick out to al-Gharbi are often strikingly simple. In the introduction, he recalls how in the fall of 2016, during his first semester as a doctoral student at Columbia University, undergraduate students claimed to be so traumatized in the wake of Donald Trump’s victory that they couldn’t do their work. Such students, al-Gharbi notes, were in fact attendees of an elite institution on their way to an elite life. As they claimed the mantle of the vulnerable and downtrodden, they focused on their own mental health rather than the material struggles of Columbia’s actual working-class community—“the landscapers, the maintenance workers, the food preparation teams, the security guards.” Al-Gharbi cast a similarly sharp eye on the pro-Palestine protests this spring, noting at Compact, where he is a columnist, that while no Columbia student “faced more than a single misdemeanor charge[,] those who faced charges at City College, the nearby public university raided by police the same night, were all hit with felonies.”

The conclusion, which becomes a starting point for the book, is that “we have never been woke.” In other words, if we conceive of wokeness as an ideology or philosophy or set of precepts, it’s not one that “woke” people generally adhere to. Rather, the woke are, in the words of the book’s subtitle, “a new elite” beset by “cultural contradictions,” which emerge from the very motivations and incentives that drove them to become woke to begin with. In another instance of sensitivity, al-Gharbi suggests that researchers in his fields tend themselves to be part of this new elite—and that their work on the sociology of elites, and on issues related to wokeness, thus suffers from persistent blind spots and biases.

The woke are, for al-Gharbi, “symbolic capitalists” whose occupations require the manipulation of words and data and who face a certain amount of inherent economic precariousness, which is compensated by higher social status. It’s widely acknowledged that writers and professors accept lower salaries for this “symbolic capital,” but al-Gharbi is the first to tie this fact rigorously to the rise of wokeness, centered as it is in these professions. The book’s perspective is perhaps best articulated in the following passage:

Elites, especially those who identify with historically marginalized and disadvantaged groups, increasingly define the relentless pursuit of their own self-interest as a “radical” act. High-end consumption is redefined as an act of “self-care” or “self-affirmation” . . . because they . . . are “worth it” and “deserve it.” Likewise, elites from historically disadvantaged groups who accumulate ever more power or influence in their own hands are described as somehow achieving a “win” for those who remain impoverished, marginalized, and vulnerable. . . . [B]ehaviors that would be recognized as exploitative, oppressive, or disrespectful if carried out by people who are white, heterosexual, or male are often interpreted as empowering, righteous, or necessary when carried out by “other” elites and elite aspirants.

In my view, al-Gharbi is more consistently correct about wokeness than any other author on the subject. He accurately traces wokeness to well before Donald Trump’s 2016 presidential candidacy, finding its origin in the Occupy Wall Street protests of 2011, attended, in his view, by many of the same people who wound up embracing full-fledged wokeness. I like to say that it started even earlier that same year: in April 2011, when the Obama administration’s Department of Education issued a “Dear Colleague” letter requiring that universities receiving federal funding adjust their procedures around adjudicating claims of sexual assault.

Indeed, at times al-Gharbi seems to suggest that the desire for more symbolic capital, for more social status, is a more essential human drive than the desire for more money; financial gains hit a threshold of diminishing returns and baseline satisfaction, whereas symbolic gains don’t seem to. And “because status is intrinsically relative . . . status competition much more closely approximates a zero-sum game.” Thus We Have Never Been Woke is ultimately not just a sociological book about a new cultural elite, the causes of the Great Awokening, or the causes of awokenings in general. It is also a philosophical book about ineliminable aspects of the human condition that draws its inspiration from concrete social circumstances.

Al-Gharbi gives a grand theory of awokenings—accounting for not only the recent Great Awokening but also social changes in the leadup to the Civil War, in the 1920s, and in the 1970s—and finds multiple threads of causation common to them.

One such thread is elite overproduction. When too many would-be elites are produced, they don’t get the standing they think they deserve, and sometimes seek to be revolutionaries instead. In cases where elite overproduction occurs simultaneously with more widespread social unrest, would-be elites can co-opt and redirect political movements toward their own goals—which, according to al-Gharbi, is often correlated with plateaus when it comes to those movements’ successes on their own terms. The biggest victories of these redirected revolutions are often “social justice sinecures,” or carved-out positions for the elites among supposedly marginalized groups.

According to al-Gharbi, elite overproduction leads to resentment and reactive calls for revolution: “Frustrated symbolic capitalists and elite aspirants sought to indict the system that failed them—and also the elites that did manage to flourish—by attempting to align themselves with the genuinely marginalized and disadvantaged.” But this isn’t completely clear. If wokeness is a legitimating ideology of a successful and powerful elite class, how can it also be a kind of formation aimed against that class by those who failed to join it? Some disentangling of this sort of tension could have helped highlight the book’s overall thesis amid the forest of fascinating detail.

In the recent Great Awokening, al-Gharbi notes with his characteristic eye, the new group of over-credentialed underachievers mostly consisted of women, and a significant majority of the jobs in the administrative bloat that was created in the wake of woke upheaval—the HR and DEI bureaucracies—went to women. Later on, he writes: “The feminization of the symbolic professions is significant in light of the robust and ever-expanding lines of research in moral and social psychology demonstrating that . . . men and women tend to engage in very different forms of conflict, competition, and status seeking.” This feminization is linked, for al-Gharbi, to the rise of a “victimhood culture” oriented in part around the concept of “trauma.” The psychology of victimhood fits the broader sense of superiority that al-Gharbi attributes to the woke symbolic capitalists: “Research has found that people who understand themselves as victims often demonstrate less concern for the hardships of others; they feel more entitled to selfish behavior; they grow more vicious against rivals . . . [T]hey also gain a sense of moral superiority relative to everyone else.”

Further, the risk-aversion and fear of ostracism that characterizes the psychology of most symbolic capitalists leads to reduced innovation in spheres as diverse as science, business, and pop culture. This section is more speculative than most, but I was happy to see al-Gharbi address the ubiquity of remakes, adaptations, and spinoffs in contemporary cultural output—just what one would expect if culture is dominated by those who have spent their lives getting better and better at following the rules. Progressive culture seems to resemble the political equivalent of bankers showing off their near-identical business cards to one another in American Psycho. Thus We Have Never Been Woke also improves on earlier accounts of wokeness by linking it to other contemporary phenomena that are obviously related but hard to associate as a matter of pure political belief.

Another such phenomenon is widespread mental illness among symbolic capitalists; al-Gharbi writes: “As symbolic capitalists’ attitudes about the social world changed, their emotional states moved in tandem.” It seems to me that it could have been the other way around; either way, I would have loved to read more on that topic.

Beyond symbolic capital, al-Gharbi introduces a new term for a kind of social status arising out of victimhood culture: totemic capital. This is the “authority afforded to an individual . . . on the basis of claimed or perceived membership in a historically marginalized or disadvantaged group.” This—along with a kind of raw assumption of totemic homogeneity—fuels, for instance, the infamous “as a” construction (e.g., “As a mentally ill Jewish-Italian man of size, I find that comment offensive”). It also explains the phenomenon of “race faking,” in which white people, especially white women, purport to be members of minority groups, just as victimhood culture itself explains the prevalence of hate crime hoaxes. Indeed, for al-Gharbi minority elites themselves are engaging in a kind of race faking, “trad[ing] on the struggles and experiences of lower- to moderate-income nonimmigrant and monoracial Black people—enhancing their own credibility and life prospects by purporting to speak on behalf of these others.”

Al-Gharbi deserves credit for mentioning these phenomena (and is even audacious enough to name Elizabeth Warren as a race faker), but he likely underestimates their importance. The problem is that his theory of totemic capital is in tension with his theory of symbolic capital as the root of wokeness. If symbolic capitalists are riding a false egalitarianism into increased social status and power, why would their theory enjoin them to cede authority to totem-bearers? If wokeness developed in the self-interest of elite white liberals, why would it involve such bowing and scraping? Why would it require the handing off of opportunities? The admission that one’s accomplishments aren’t really one’s own, but rather the result of privilege and discrimination? Why do woke whites so favor affirmative action that might hurt their own prospects?

This is where al-Gharbi’s own forms of theory-building, based on various forms of capital, cause him some blindness of his own. Examining the quasi-religious aspects of wokeness would have been useful in this context; his account of symbolic capitalists as self-interested could be rescued if the interest in question is some sort of purging of their souls of original sins, like unconscious bias. And, since al-Gharbi sometimes seems to place wokeness mainly in the minds of white liberal symbolic capitalists, it would make sense to acknowledge that totem-bearers don’t have to be woke in order to gain the sort of symbolic capital that woke whites seem to want. In fact, one might regard wokeness as simply parasitic on the totemic capital that al-Gharbi describes—an essentially derivative phenomenon that is, in some sense, a kind of anti-whiteness.

Similarly, though al-Gharbi analyzes symbolic capitalists’ divergence from their stated egalitarian ideals, he doesn’t seem to question the intuitive appeal of those ideals. This is so even though the apparent hypocrisy seems related to other phenomena he’s skeptical of, like victimhood culture. The third chapter, titled “Symbolic Domination,” begins: “Who are the elites? In contemporary America, it seems no one wants to adopt the label.” But of course elitism is in tension with egalitarianism. At a philosophical level, it’s hard to know how we can evaluate wokeness without evaluating the various egalitarian claims that underpin it. This relates to another tension throughout the book: though at some points al-Gharbi suggests that the woke ideology, with its purpose of legitimating the position of elite symbolic capitalists, is held as a genuine set of core beliefs, at others he seems to suggest that it’s held opportunistically or as a mere pretense.

Because academic and journalistic elites are symbolic capitalists, political analysis of disagreement from dominant elite views in the academy and media often falls into the diagnostic mode. Sharply combining critiques of discourses around terms like “fascism” and “misinformation,” al-Gharbi writes that “interpret[ing] deviance from, or resistance to, our own preferences and priorities in terms of pathologies . . . or deficiencies. . . . Inconvenient social movements are typically explained in terms of some noxious counterelite.” But surely, for all its many virtues, We Have Never Been Woke is a similar kind of diagnostic text, which falls into similar patterns. Al-Gharbi claims, for instance: “Although our language often makes appeals to solidaristic altruism, symbolic capitalists primarily deploy political discourse . . . for the purposes of individual enhancement and personal expression.” Perhaps pathology and deficiency are two of the only options we have when it comes to theorizing about ideology.

It would take too long to catalog all the terrific details and vignettes that made their way into this book. To show that symbolic capitalists often win against the superelite, al-Gharbi mentions the case of Henry Ford II losing out against the social-justice orientation of the Ford Foundation. Discussing campus politics, he writes that “many student clubs at Yale are explicitly oriented around social justice but are also highly competitive to get into.” Virtually every aspect of contemporary culture gets some sort of mention and ends up being related in some way to the same forces that have generated wokeness. We Have Never Been Woke is a great book on wokeness, probably the most incisive and interesting one that’s been written. It also holds appeal as a work on political beliefs, as a work of political sociology, and as an incredibly well-sourced piece of cultural criticism. It is very much worth reading.

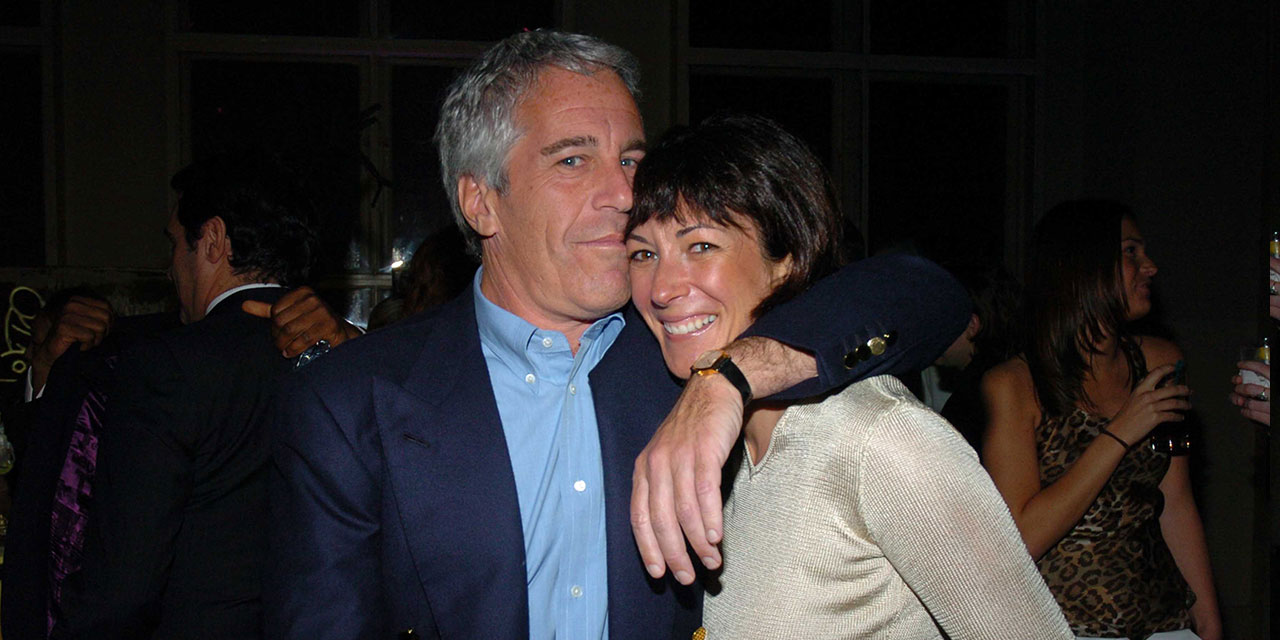

Photo: nemke / E+ via Getty Images