Five years ago, New York proved how easy it is to shut down a city by decree. In mid-March 2020, under a state and local Covid-19 lockdown that lasted, in varying forms, until the summer of 2021, the city’s restaurants, stores, theaters, and hotels abruptly closed, and its subways and streets emptied.

Since then, New York has proved something else: it’s far harder to start a city back up. Even after offices partially reopened in June 2020, many workers stayed home, leaving nearby eateries and shops empty. Broadway stayed dark for more than a year, and as habits changed, reopened theaters filled fewer seats. Some shifts were positive, or at least softened the blow—outer-borough neighborhoods benefited as people spent more locally—but high post-pandemic costs, driven by inflation, mean that even busy restaurants now struggle to break even. Idleness—fueled by school closures, reduced in-person mental-health services, and a pre-Covid turn toward criminal-justice leniency—has worsened crime and disorder.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

Across two paired governorships and mayoralties—those of Andrew Cuomo and Bill de Blasio, followed by Kathy Hochul and Eric Adams—New York’s leaders compounded these stresses with missteps of their own. They failed to control looting during the summer of 2020, for instance, and they did little to ease the rising tax and fee burdens on small businesses as inflation surged. By 2023, the city’s mismanagement of the migrant crisis had turned nearly 200 hotels into city-funded shelters, rather than using these spaces to welcome back tourists.

And yet, New York is surviving—if not thriving—defying the worst pandemic-era predictions. Few today would call the city “completely dead,” as James Altucher infamously did in 2020. But to a visitor from 2019, today’s city would feel “off”: more fragile, less safe. Life often seems normal, but success is measured by clawing back what was lost. You notice that you’ve taken 20 subway rides without incident. You realize, at 3 am, that the drag racing that once kept you up has quieted. Going to the theater no longer feels miraculous; seeing someone in a mask is now less common. Both crime and economic data reflect this uneasy normal: things are okay, but far from where they could be—and where they were, not long ago.

New Yorkers from all walks of life—retail managers, tenement owners, residents from Greenpoint to Fordham Road—experienced the pandemic’s early months differently, and they are now navigating an uneven recovery. A half-decade ago, as Covid still defined day-to-day life, City Journal profiled more than half a dozen New Yorkers, capturing their struggles and hopes for the city. Five years later, how are most of them doing—and how can New York do better?

Statistics highlight New York’s uneven recovery. How you see it depends on what business you’re in and with whom you’re comparing yourself. On the surface, the city’s economy appears to have bounced back—something unimaginable in spring 2020. In December 2019, New York had a record 4.160 million private-sector jobs. By December 2024 (the most recent data available), that number had grown to 4.246 million—a nearly 2.1 percent increase. Considering that one in five jobs had vanished by May 2020, this is no small feat. More economic activity is also visible on the transit system, though work-from-home habits persist: subway ridership hovers just above three-quarters of pre-Covid levels.

Yet compared with the national recovery—or New York’s own past—these indicators look less impressive. Nationwide, by December 2024, the country had 4.9 percent more jobs than five years earlier. And consider how quickly New York rebounded from previous crises: five years after the September 11 attacks, the city had added 4 percent more private-sector jobs; five years after the 2008 financial crisis, it had gained 8.9 percent more private-sector jobs.

The city’s job mix has shifted significantly since the Covid lockdowns. The laptop crowd—back in the office at least a few days a week—has fared well, buoyed by a national economy that continues to grow. Outside of finance, professional and business services—including much of the tech sector—make up New York’s largest private-sector employment base after the heavily government-subsidized “eds and meds” sector. As of December 2024, the city had nearly 800,000 professional and business service jobs, 1.1 percent more than before Covid. Finance and insurance have done even better, though from a smaller base, adding 5.3 percent more jobs, for a total of 368,200.

Other sectors have struggled. With commercial real estate in a prolonged slump, real-estate jobs are down 2.8 percent over five years, to 134,600. The information industry—including print and broadcast media—has been hit hardest, losing 8.3 percent of its jobs (now totaling 206,500), reflecting longer-term, Internet-driven declines in ad revenue more than pandemic-related effects.

The pandemic took its heaviest toll on industries that have long provided steady work for hundreds of thousands of New Yorkers without college degrees—or even English skills. The city’s retail sector is still missing tens of thousands of jobs, with employment down 14.9 percent since 2019, to 309,100. Leisure and hospitality have fared slightly better but are 3.7 percent below pre-Covid levels, at 456,600 jobs. Within that sector, arts and entertainment have lost 8 percent of their pre-pandemic workforce, now employing 88,000, while full-service restaurants are down 4.4 percent, employing 162,300.

As for crime: through the first two months of 2025, New York has seen some welcome news, with felony crime down 15 percent compared with the same period in 2024. The bellwether category of petit larceny has also dipped 5.5 percent. Yet both are still far higher than in 2019—up 22.1 percent and 29.6 percent, respectively. Still, on his fourth attempt, Mayor Eric Adams in November 2024 finally appointed a capable manager, Jessica Tisch, as police commissioner. The city also stands to benefit from recent adjustments to the state’s 2017–19 criminal-justice reforms, which now give judges greater discretion to detain repeat offenders.

These broader trends are reflected in personal stories. After three months of pandemic closure, New York began reopening its restaurants in June 2020—at first, only for outdoor dining, one of the few bright spots of that dark summer. Curbside and streetside cafés have since endured, bringing new life to neighborhoods. Anella, then a 12-year-old bistro in Brooklyn’s well-kept, mid-rise Greenpoint, reopened to enthusiastic support from the professional work-from-home crowd, still hunkered down locally rather than commuting to Manhattan. But even with a flexible landlord who didn’t immediately demand back rent, Anella struggled with challenges like government-mandated reduced seating capacity, its then-owner, Blair Papagni, told me at the time.

Anella closed for good in 2022. It’s hard to say for certain why any particular restaurant shuts its doors, says Andrew Rigie of the New York City Hospitality Alliance, which represents the industry. But he notes that restaurants have contended since 2020 not only with back rent payments but also with rising costs for labor and ingredients. “Operating costs continue to rise,” he observes, with “sales at many restaurants slumped through January and February” and some restaurants “still burdened with pandemic-era debt,” owed to both landlords and financial backers.

Yet Anella’s fate is also a story of urban adaptation. The storefronts along Greenpoint’s main streets are today well-occupied and eclectic, thanks to the neighborhood’s mix of residents, from high-earning newcomers to longtime homeowners and renters. Office workers spending a few days a week working from home are still eating and shopping a lot in their own neighborhoods. By last summer, a new restaurant had taken Anella’s place—Mariscos El Submarino, the second location of a popular Jackson Heights seafood spot. The coolly lit space, co-owned by a couple with Mexican roots, features cartoon sea creatures on the walls and a brightly colored bar. One recent afternoon, as customers browsed menus and a man worked on a laptop, a waiter told me that business was good.

The contrast between Anella and its successor also underscores how Covid accelerated a trend in all but the wealthiest neighborhoods: a shift from elaborate full-service restaurants to mid-price places with simpler menus. This change can also be seen in the rise of high-end bakeries across Manhattan. Selling $5 croissants and $9 pastries, these bakeries aren’t cheap, but they offer affordable treats compared with restaurant meals, and their high-volume, high-margin model suits high-rent areas.

The city can’t and shouldn’t try to save individual restaurants, but it could do more to support the industry. As Rigie observes, New York could ease the burden on owners still struggling with post-pandemic challenges by streamlining permits for the permanent outdoor dining program that replaced the temporary Covid-era version. It could also be more flexible in allowing covered outdoor cafés during winter, as it did during the pandemic but stopped doing last year. And though city hall has long vowed to eliminate sidewalk scaffolds—meant to protect pedestrians from falling debris during building inspections and repairs—they remain prevalent for months on end, crowding outdoor dining spaces and deterring customers.

In Manhattan’s Chinatown, “for lease” signs are more common than in Greenpoint. The area has been hit by the ongoing loss of warehouse-style supply stores, the slow recovery of global tourism (with high-spending visitors from China still largely absent and others taking shorter trips), and the sluggish return of downtown office workers. Five years ago, Jan Lee, a longtime civic leader and small-property owner with three generations of family ties in the neighborhood, worried about the post-lockdown future of one of his commercial tenants. Today, that tenant—a small high-end cosmetics store—continues to struggle and owes significant back rent. Even as Lee has deferred payments and may lose the tenant, he notes, “I still have to pay my property taxes.”

Lee explains why Chinatown’s longtime property owners rely heavily on income from ground-floor retailers and restaurants. In mid-rise buildings like the tenement he owns, most residential tenants are rent-regulated and many have lived there for decades. These long-term tenants pay very low rents—sometimes not even three figures monthly.

Lee by no means advocates displacing low-rent tenants, but he notes that a 2019 change by the state legislature has made it even harder for property owners to keep up with costs. The law sharply limits how much owners can invest in rehabilitating apartments when they become vacant and new tenants then move in. Now, owners can pass through only $50,000 in costs—spread over 12 to 13 years—and only if the previous tenant lived there for 25 years or more. At a minimum, Lee says, the regulation “needs to be linked to square feet.” He adds that, during the pandemic, even when units became vacant, many owners were “afraid to rent,” worried about getting involved with un-evictable squatters.

Even as it has grown harder to earn income from these properties, city property taxes keep mounting. In one Mott Street building, taxes increased from $56,000 to $96,000 over 14 years. Taxes often outpace building income because the city assesses properties like Lee’s partly based on their potential value, not actual cash flow. Lee knows of three tenement properties in the area now in foreclosure.

He nevertheless is optimistic about Chinatown, in part because Covid sparked renewed civic engagement, especially among younger residents. Several new nonprofits “are doing amazing work,” he says, including Welcome to Chinatown, cofounded by Victoria “Vic” Lee (no relation), whose family has lived in the neighborhood for three generations. Before the pandemic, she worked in corporate travel for a Fortune 500 company. As lockdowns began, she and partner Jennifer Tam launched the nonprofit to help local businesses survive. Recognizing that one-size-fits-all solutions like gift cards didn’t suit Chinatown’s cash-based culture, they raised funds to buy meals from local kitchens and deliver them to essential workers. Throughout 2020, Lee says, “we were making deliveries, making payments” to shuttered or struggling restaurants. What began as a temporary fix, she now realizes, addresses “complex and deep” challenges facing the neighborhood.

The pair are putting their corporate skills to work to connect would-be entrepreneurs with property owners and area investors, suppliers, and customers, recently launching Welcome to Chinatown’s new “small business innovation hub.” Located in a central storefront on the Bowery (formerly a plumbing-supply store), the hub hosts networking events to match potential funders and entrepreneurs as well as tutorials and will offer co-working space by reservation. One theme is succession planning: owners of small family businesses, including the fresh grocery stores on which Chinatown residents rely for cheap, quality nutrition, may not know how to pass down or sell a business.

A further idea is to connect small-property owners with potential tenants. Welcome to Chinatown could also create “incubation spaces” to help identify the right long-term tenant. If a potential tenant and landlord are hesitant to commit to a standard five-year lease, Welcome to Chinatown may offer grants to help defray the rent, with the assistance shrinking as the business gets established.

Another problem that Chinatown has faced since the pandemic is largely within the city’s control: soaring crime and disorder. “It feels like it’s the 1970s out here,” says Jan Lee. The area’s crime rate is now 17.2 percent above 2019 levels. Chinatown has also been shaken by high-profile incidents of random violence, hate crimes, and killings—including the 2022 death of Christina Yuna Lee, murdered by a longtime violent offender who had been released on bail for an earlier subway crime.

At a recent public outdoor event, Lee recalls, he invited the Guardian Angels volunteer anticrime patrol to be on hand in case of trouble. The Angels peacefully intercepted one agitated vagrant, offering him water and calming him down. But unarmed civilians can only do so much without effective law enforcement and adequate mental-health treatment—both of which, despite some recent progress, continue to lag.

The streets of Manhattan’s downtown and midtown business districts are no longer depopulated, but both continue to be affected by other Covid-associated trends: the shift from in-person to online shopping and remote work. No, office workers aren’t in their pajamas five days a week anymore, but they still tend to come in only two or three days a week, instead of four or five; a mid-2024 Partnership for New York City survey of white-collar firms found that in-office work had recovered to slightly below three-quarters of pre-Covid levels—and plateaued.

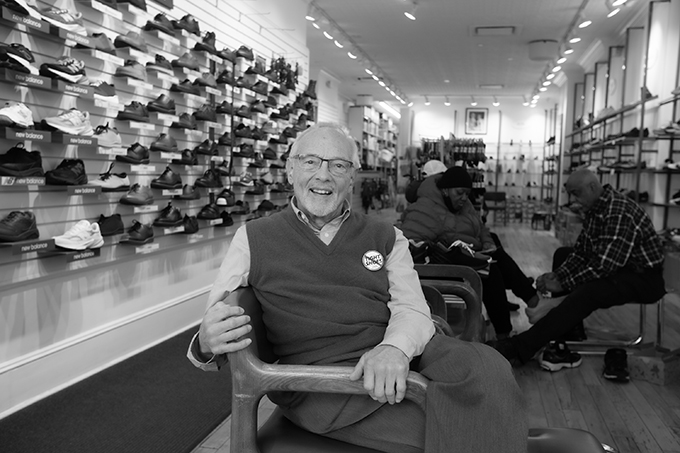

Five years ago, Robert Schwartz, owner of Eneslow Shoes—a century-old retail enterprise that his family has run for nearly 60 of those years—made a trenchant observation about his two Manhattan locations: “The problem with Manhattan business is that there is no business,” he said. Business at his Park Avenue store, just south of midtown, had fallen 97 percent when he reopened after the six-week Covid shutdown. Today, that store is shuttered, never having recovered more than 20 percent of its pre-pandemic business. Schwartz has one location left in Manhattan, on Third Avenue, and another store in Queens. The Manhattan retail business, he says, “has been far worse than my greatest fears.”

Schwartz says that Covid lockdowns sped up shifts already under way, with an estimated 70 percent of mid-price shoe shopping now done online. Manhattanites, he says, “won’t even cross the street” to shop in person. Work-from-home also left lasting habits, like dressing casually for the office. “They’re all walking around in their Hokas,” he says of former customers, who have traded seasonal and dress shoes—“winter boots, summer sandals, special-occasion shoes”—for pricey sneakers, even at banks and law firms. Though Schwartz stocks Hokas, many customers buy them online. His two remaining stores survive partly because competitors have closed.

The fate of one shoe store may seem insignificant, like that of one restaurant. But Schwartz’s story is echoed in those of thousands of small stores—many independently owned—selling clothes, appliances, bicycles, housewares, and more. Schwartz once employed 35 full-time workers; now it’s 20, many part-time. As big banks and drugstores also close branches, commercial real-estate investors are left with millions of square feet of vacant retail space, especially in core Manhattan, and no clear idea of how to fill it. One expanding replacement—the urgent-care medical industry—is heavily subsidized by government health insurance. And city policy has made things worse. In core Manhattan, retail tenants paying over $250,000 a year in rent still face a “commercial rent tax,” Schwartz observes, though they already contribute to property taxes through their landlords.

To thrive in the post-Covid, heavily online Manhattan retail world, brick-and-mortar retailers need to offer a unique product. Mood Fabrics, a two-story emporium tucked upstairs in an older Garment District building, does that. One recent mid-afternoon weekday, about two dozen customers, from Italian tourists to professional buyers, perused the store’s rolls of cotton, silk, and wool. “This is an experience,” says manager Eric Sauma. “People need to see it, touch it.” Five years ago, emerging from full lockdown, Sauma estimated that he was doing about half of his pre-Covid business; now, business is almost back to normal. Mood Fabrics has flourished with the reopening of Broadway shows and the revival of tourism. The company may also marginally gain from the impending closure of Joann Fabric, a national mainstay, he says.

Five years ago, Sauma voiced concerns about growing disorder in the area, just south of the Port Authority Bus Terminal and not far from Penn Station. Though he still thinks that “the city should do something” about the problem, he has grown wearily used to it, and he has a new anxiety: national tariffs on imports. He notes that “a lot of material”—fabric—“still comes from China” and thinks that, if the Trump administration must levy tariffs, it should do so on finished products, not on raw materials.

North of Manhattan on the Bronx’s Fordham Road, a commercial thoroughfare, retail is a different business, partly because many customers get paid in cash and therefore must pay cash themselves, and partly because customers don’t have secure spaces for package delivery. Just under five years ago, the biggest concern of Wilma Alonso, president of the Fordham Road Business Improvement District, wasn’t nearby residents’ lack of money to spend—most people who had lost their jobs fully replaced their income via extraordinary federal benefits—but the looting that hit the area during the first week of June 2020. Most businesses “have recovered from the looting,” Alonso says. In the past few years, the road has become a “sneaker mecca,” with “the highest concentration of stores that sell sneakers per capita in the whole country.”

But, she says, the 2020 looting was a “foreshadowing of the awful consequences from the bail reform laws. It’s what has made retail theft in New York City, including on Fordham Road, challenging. While the looting was a short-term circumstance, retail theft has been a long-term consequence of bail reform.” The area’s foot traffic has recovered, with most people having returned to work, and it has even seen some adaptation of its own, with new chain restaurants opening. But “we are still trying to navigate the numerous quality-of-life issues our businesses face,” Alonso says, particularly an increase in illegal street vending, with untaxed merchants who don’t pay rent selling wares on the street, in competition with storefront vendors who must comply with local and state laws. “It is affecting businesses’ bottom lines.” Alonso appreciates Governor Kathy Hochul’s efforts to put more money in customers’ pockets, via the tax rebates that the governor has proposed in her latest budget, but says that “leaders in Albany [should] visit one of our businesses, talk to a business owner who is struggling with rising costs and the day-to-day of simply doing business,” and consider “reducing bureaucracy.”

Five years ago, Jordan Barowitz, then with the Durst Organization and now running Barowitz Advisory, predicted that people would return to the office—and he was partly right. His biggest concern at the time was city hall’s inertia in encouraging that return. Mayor Adams, for all his flaws, has improved on Bill de Blasio in one respect, Barowitz says: he understands the importance of getting workers back to their desks. “The city has certainly rebounded from Covid,” Barowitz notes, “but there’s been a certain inelasticity that’s troubling for New York and its history of amazing bounce-backs. Quality of life and public safety haven’t returned to pre-Covid levels.”

Commercial real estate, he adds, is a “tale of two markets,” with premier, Class A buildings thriving, while older ones struggle. In retail, “the outer boroughs are stronger than pre-pandemic,” but midtown and downtown “haven’t fully come back.”

One positive post-pandemic sign, Barowitz thinks, is closer attention to the city’s housing imbalances. The City of Yes—Adams’s program to incentivize developers to build more housing—“is a great thing . . . a substantive step in the right direction.” But the plan, which anticipates 6,500 new units a year, won’t unleash enough construction to bring prices substantially down. One issue is that “the economics of building rental housing are just not there, despite rents being so high.” The reason: “land, construction, operating costs are through the roof.”

If multiple industries are holding their own in New York, one has surged: tech. Five years ago, Julie Samuels, executive director at the Tech:NYC trade group, told me that tech was the only industry actively bullish on the city, leasing more space even as other types of employers were pulling back on new rental agreements.

Her optimism has held up. Google, for example, has doubled its workforce since 2018, to 14,000, and last year expanded its local headquarters by opening the refitted St. John’s Terminal, originally a port facility, downtown. OpenAI has just leased floors in SoHo’s historic Puck Building—more proof that New York’s older properties can be an asset as new businesses adapt them.

A big subset of tech workers, Samuels says, love living in the city; they are “committed New Yorkers who just happen to work in tech.” Engineers enjoy watching how complex systems work, or don’t work, and New York is a complex system. “They’re systems people,” she says, “always thinking about trying to make things work better.” Hybrid workweeks, too, function better in places like New York than in those built around long car commutes, such as Silicon Valley; workers here can take short subway rides or walk to the office.

From a tech standpoint, the city also has benefited from relative success. Though New York’s quality of life has deteriorated, tech hub San Francisco’s is worse. In the decade leading up to and through the pandemic, Samuels says, “San Franciso felt a lot more unsafe.” But while residents and businesses looking to leave the Bay Area have been an “opportunity” for New York, she cautions, they’re also a “warning”: if crime and disorder persist or worsen, people and companies will look elsewhere.

New York’s arts industry was the last to reopen after Covid, with theaters closed well into 2021, and it is besieged today. One challenge is its inflated cost structure: live performances require real, live people—musicians, actors, museum guards, and so on—whose living costs keep going up. Since Covid, the Met Opera has drastically cut the number of annual productions, and Broadway attendance is below pre-pandemic levels. Eye-watering ticket prices, often over $100, are as much a sign of difficulties as success—productions can’t survive without them, but they deter repeat customers. This spring, the Guggenheim Museum announced layoffs.

Another major headwind for the arts is its dependence on out-of-towners. “We’re starting from almost zero, in terms of how long it will take tourists to come back,” said Ken Weine, a longtime arts executive, in 2020 when he was at the Met Museum (he has since moved on). Five years later, tourists still haven’t fully returned. “It is a very complex time for the cultural sector,” Weine says. New York’s institutions continue to produce “world-class” work, despite soaring rents and costs—as anyone who has seen an off-Broadway show recently can attest. But a key post-Covid reality is that many big-spending international visitors are staying away. Pre-pandemic, New York drew a million visitors from China alone; now only a small fraction of that number are coming to the city. Making matters worse is the collapse of small media outlets that once provided free advertising through show listings, making it “much more difficult and expensive” to reach audiences, says Weine.

To look now at photos of Manhattan from spring 2020 is to glimpse a world that hardly seems real: Times Square empty, the Met Museum steps deserted, restaurants shuttered with hand-lettered messages promising a quick return, subway cars devoid of passengers. New York has moved beyond those eerily silent days and the dystopian chaos that followed. It’s a good sign, for example, that storefronts weren’t boarded up before last year’s presidential election, unlike in 2020, when months of looting preceded the vote. But today’s city is far from its pre-Covid normal. The greatest risk, five years on? That in the absence of crisis, New York will settle for stagnation.

Top Photo: “It feels like it’s the 1970s out here,” says Jan Lee, a longtime Chinatown property owner and civic leader concerned about crime and disorder in the neighborhood. (Photo by Harvey Wang)