America has always contained striking economic disparities, particularly along geographic lines, but those that exist today are different, and more disturbing, because they seem more permanent. Poorer areas are no longer catching up with richer ones. Migration rates have fallen dramatically, and joblessness has become a fixture of many local economies.

From the perspective of New York or Silicon Valley, it’s tempting to divide the country between the prosperous coasts and the faltering flyover states, but that simple dichotomy is misleading. Our pacesetting coastal cities are extremely successful, but much of what I will call America’s western heartland enjoys growing employment, with low joblessness, including Minnesota, Texas, and the Dakotas. In my analysis, I divide America’s 48 contiguous states into the coasts, the eastern heartland, and the western heartland. The split between east and west is based on whether the state joined the union before 1840. This framework produces a more accurate view: that there is a band of economic dysfunction in America’s eastern heartland, starting in the Mississippi Delta, running through Appalachia, and ending in the Rust Belt. The eastern heartland is ground zero for rising male mortality, the opioid crisis, and social-welfare dependence. Industry has fled the eastern heartland for decades; manufacturing has happily relocated to the better-educated, more pro-business western heartland. In a postindustrial America, capital has little incentive to relocate to low-wage areas. Out-migration takes the form of an exodus of the skilled, which leaves struggling regions further lacking the human capital that could spark economic regeneration.

The dire social problems of the eastern heartland, particularly long-term joblessness, call for a serious policy response. The best way to reduce joblessness is to make work pay more, for employees and employers, by reducing the implicit tax on employment generated by social-welfare policies like disability insurance and SNAP payments (food stamps), which discourage work because benefits get cut when an individual exceeds a certain threshold of earned income; and by expanding policies like the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), which subsidizes working. The need to make work pay more is particularly acute in the eastern heartland, so we could subsidize work more in that region. Education reform is at least as important, and community colleges must do more to train employable students. Finally, the eastern heartland should become more business- and entrepreneur-friendly by reducing regulation.

In the decades after World War II, the income differences across American regions shrank. In 1950, Mississippi was America’s poorest state, and 18 other states enjoyed incomes more than twice as high. Today, Mississippi remains America’s poorest state, but no other state doubles its per-capita income.

America was then a country of migrants. African-Americans fled the Jim Crow South to northern cities of opportunity. Urbanites left behind their crowded apartments and embraced car-based living in the suburbs and exurbs. Industrial capital and Rust Belt capital moved to the warmer, more pro-business Sun Belt. Between 1950 and 1992, more than 6 percent of Americans moved across counties every year.

The free movement of workers and capital narrowed America’s economic differences. The long-impoverished South got richer, as industry moved in and many of the poorest moved out. The gap between white and African-American earnings narrowed substantially, partially because of the Great Migration northward.

Migration has been an economic engine for America, as well as a safety net. Nineteenth-century farmers became far more productive by abandoning New England’s poor soil and moving to Iowa and Illinois. John Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath tells how the Joad family flees Oklahoma and the Dust Bowl and eventually finds hope on the West Coast. Their regional flight to safety mirrors the much longer trips taken by immigrants who found in America a refuge from the potato famine and the Cossacks’ charge.

For 350 years, American migration and immigration were abetted by ample living space. Chicago innovators like George Washington Snow and Augustine Taylor developed the balloon frame in the early 1830s, making home-building cheaper and easier for the nineteenth-century farmers who moved west. Few rules limited the tenements built for the new residents of nineteenth-century New York and Chicago. New York permitted 100,000 units annually in the early 1920s. After World War II, mass suburbanization made abundant land available, and a white exodus freed up urban space for African-Americans coming north.

But U.S. migration rates have dropped substantially over the last quarter-century. Since 2008, the cross-county migration rate has never risen above 3.9 percent, less than two-thirds of the pre-1992 minimum migration rate. Economists Peter Ganong and Daniel Shoag have found that while migration flowed strongly to high-wage areas between 1940 and 1960, that process stopped in 1980. Only the very skilled still move in large numbers to high-wage, high-cost areas, like Silicon Valley.

Changes in the housing supply have contributed to making America no longer a nation in motion. Since 1965, regulations have limited building in America’s most productive areas, including New York, Boston, and Greater San Francisco. Productive cities can’t grow without new housing, and without enough housing supply, they become unaffordable to ordinary Americans. Many low-skilled workers would get a wage boost by moving from Detroit to San Francisco, but that increase wouldn’t cover Bay Area costs of living.

The evolution of work may be an even more important cause of America’s growing immobility. Historically, agricultural productivity depended mainly on the combination of muscle and soil quality, so nineteenth-century American farmers moved in search of better farmland. Industrial productivity depended on worker grit, machines, and smart leadership. Industrial innovators produced enormous numbers of jobs for less educated Americans. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, innovators like Henry Ford largely stayed put in their northern redoubts, with easy water- and rail-based transportation access to the world. But Ford’s automated assembly line offered workers five-dollar days, which induced hundreds of thousands to come to Detroit. After World War II, capital and managers, like the fictional industrialist whose murder motivates the classic 1967 film In the Heat of the Night, moved south to take advantage of low-cost, nonunionized Southern labor. As University of Minnesota economist Thomas Holmes’s research shows, industry increasingly moved from pro-union to right-to-work states after 1947.

The postindustrial world doesn’t rely much on muscle, however. The innovations of the insightful are more likely to need other machines and other skilled workers. The Googleplex is a hub for the highly skilled, not 100,000 assembly-line laborers, and Google’s success provides little reason for less skilled Americans to decamp to Mountain View. Nor is there much reason for Google to consider relocating to Appalachia to reduce labor costs. Some Southern cities, like Austin, Atlanta, Charlotte, and Raleigh, compete effectively by offering a combination of high skills, lower costs, and business-friendly government, but cheap, unskilled labor has little appeal in our automated age. Even old-economy industries, such as car manufacturing, have become so capital-intensive that they can no longer be drawn to an area by cheap, unskilled labor. The prototypical low-skill job today, and of the future, is in the service sector, because machines can replace the heft of a bicep more readily than the charm of a smile. The service sector thrives where other industries, such as finance or technology, generate plenty of spending money. Consequently, in New York, Dallas, and Boston, among other economic high-achievers, service employment abounds.

Even in highly productive areas like San Francisco, though, service-sector wages are limited by innovative, online alternatives. As long as Amazon Prime beckons, the salaries of local salespeople can’t be that high. As long as “grocerants” sell precooked meals, how much can fast-food workers’ wages grow? Only health care and social assistance remain relatively immune to technology-induced downsizing, because the federal government pays much of the bill.

In the agricultural and industrial age, people and capital moved over space to correct temporarily high or low wages: in our age of information and services, little impetus exists for skills and capital to relocate to low-skill, low-wage areas. Even the service economy, employing fewer low-skilled people in wealthier areas, seems to have a limited appetite for employment growth. Consequently, while local unemployment and low wages were temporary phenomena in the age of manufacturing, they have become more entrenched today.

“Declining male employment reflects less demand for brawn and more unwillingness of men to work for low wages.”

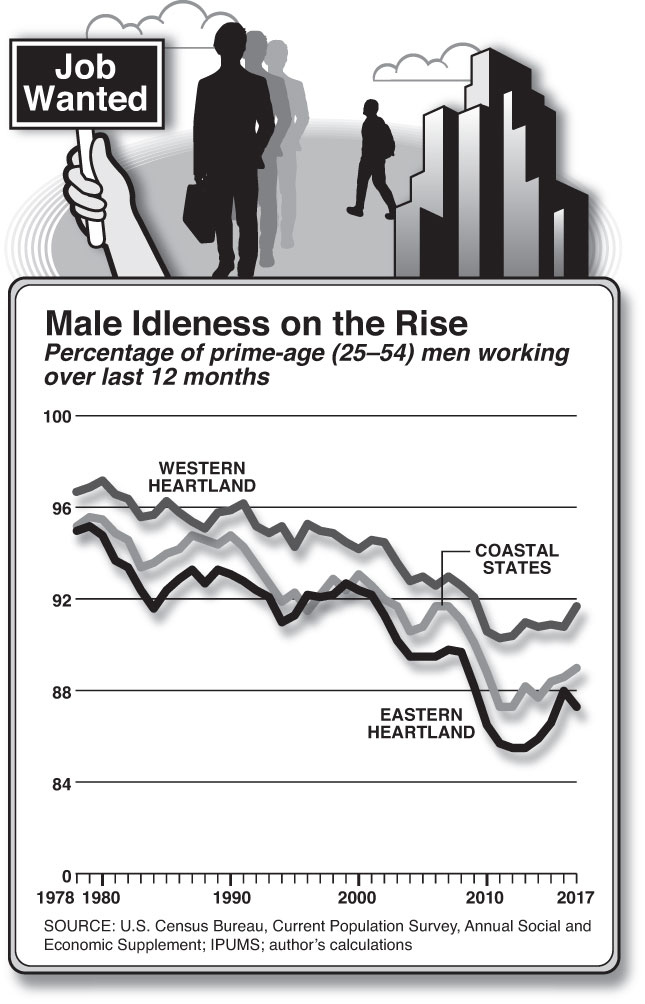

America’s geographic sclerosis has been accompanied by a national increase in male joblessness. The two phenomena reflect similar forces, especially the changing nature of work. I focus on male joblessness, primarily because female labor-force participation is a more complex phenomenon and because the lives of nonemployed men look quite different from the lives of nonemployed women.

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, 95 percent of men between 25 and 54 were regularly employed. Since 1970, the share of nonemployed men has risen steadily. For much of the past decade, more than 15 percent of these “prime-aged” men have been jobless. This drastic change can be missed by looking only at the unemployment rate, which captures the share of jobless men looking for work. Nowadays, most nonemployed men have given up looking for work.

National nonemployment numbers hide enormous and persistent spatial disparities. In Alexandria, Virginia, less than 5 percent of prime-aged men are nonemployed, whereas in Flint, Michigan, male joblessness exceeds 35 percent. Moreover, these gaps have become distressingly permanent. Every census micro-sample area with a male joblessness rate higher than 10 percent in 1980 also had a joblessness rate above 10 percent 30 years later—and much higher than 10 percent, in many cases.

Declining male employment reflects both reduced demand for human brawn and an increasing unwillingness of men to work for low wages. (See “The War on Work,” The Shape of Work to Come, 2017.) Real wages for poorer Americans have grown slowly, but they are still higher today than they were in the late 1970s. Uber is an employment option for almost everyone with a car. Yet far fewer men choose to work today than they did in the past. In 1955, and even more so in 1905, if a man didn’t work, he didn’t eat. A jobless man certainly didn’t live in a decent house and watch television for five hours a day, which is the daily average for nonemployed men.

Average household income for men who have been jobless for over a year is $38,200, which reflects a combination of other earners in the household (parents as well as partners) and public generosity. More than four-fifths of long-term jobless men live with someone else, and their family income exceeds $42,700. The situation is much tougher for the 15.1 percent of jobless men who live alone. Most of their $12,700 average annual income comes from public sources, especially disability insurance.

Private and public generosity has made joblessness less horrific; it has also reduced the incentive to get a job. Moreover, the rules surrounding well-meaning public programs have increased the costs of earning more. Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) payments will stop if an individual earns more than $1,180 per month. Section 8 housing vouchers and food stamps generate implicit taxes on earnings. These public benefits do reduce poverty—but they also discourage working.

America’s primary social-insurance programs are national in scope, but they are administered at the state or even housing-authority level. Yale Law professor David Schleicher has argued that the difficulties in transferring benefits across space may also reduce migration and hold people in depressed housing markets. Housing advocates have long worried that Section 8 housing vouchers depress the migration that can create upward mobility.

A copious literature reveals that joblessness is far more damaging than income inequality. Joblessness is strongly associated with suicide, opioid abuse, and family breakdown. The share of men who report that they are unsatisfied with their lives is 2 percent among employed men with annual family earnings of more than $50,000, 4 percent for those employed with family earnings between $35,000 and $50,000, and 7 percent for those employed with family earnings below $35,000. These numbers seem low relative to the 18 percent of the jobless who report themselves unsatisfied with their lives. These connections become highly visible in the geography of prime male joblessness in the United States.

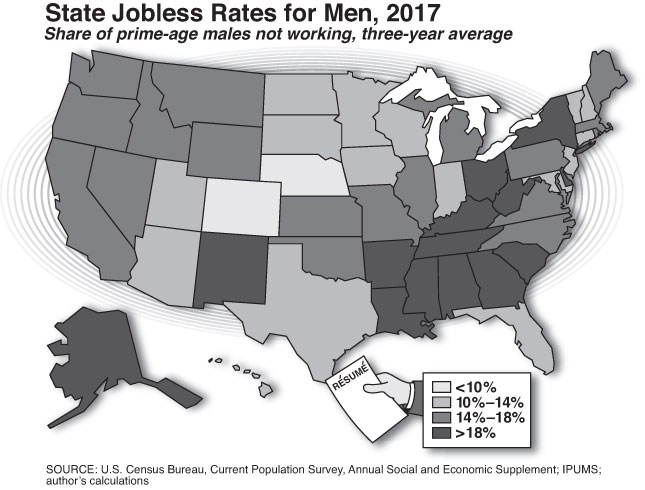

Male joblessness is highest in the eastern heartland, starting in Louisiana and Mississippi and running up through Appalachia into Ohio and Michigan. This spatial pattern can also be seen for opioid use, or per-capita spending by the federal government, which is highest in the most desperate areas. (The pattern for female joblessness is different and more north–south, perhaps reflecting the South’s more traditional social norms.) The map on page 39 illustrates that the eastern, but not the western, heartland states are where nonworking males are concentrated—and the areas where the rising mortality levels identified by Princeton professors Anne Case and Angus Deaton are most pronounced.

The map makes several key points about America’s three regions. First, joblessness is actually lowest in the western heartland, not on the coasts. That means that high-density, high-education San Francisco’s isn’t the only economic model that promotes employment. Texas and the Dakotas also have low joblessness rates, and for the eastern heartland, their models may be far more relevant than Silicon Valley’s.

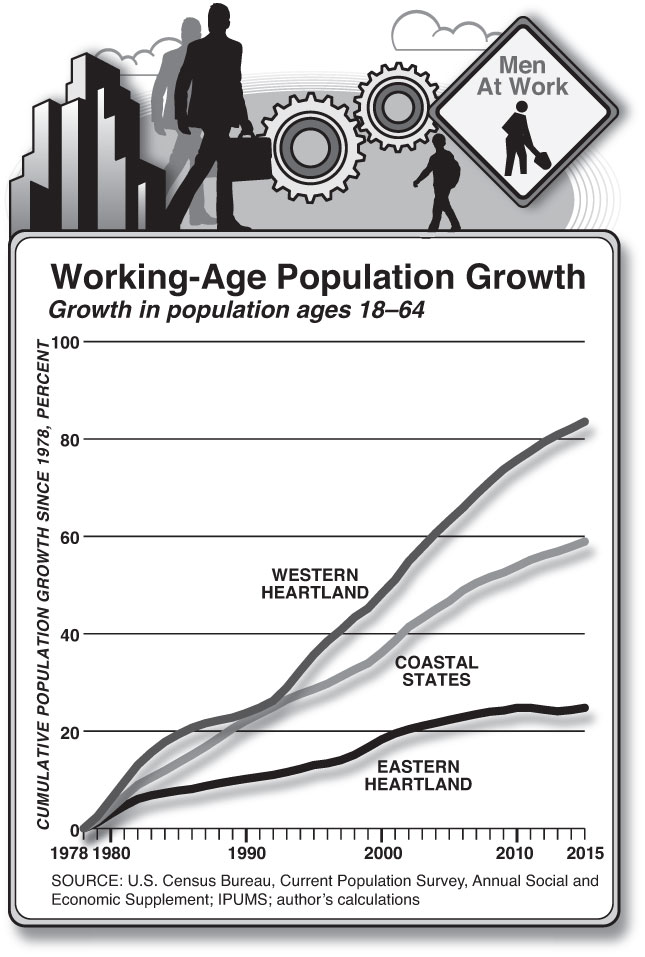

Second, while overall GDP has grown at a roughly equal rate for the coasts and the western heartland, the two regions have experienced success in different ways. Per-capita income growth has been higher on the coasts, and incomes are now much higher in coastal America than in the other two regions. But the growth in the working-age population has been much faster in the western heartland than in the other two regions. This dichotomy should be familiar. When Texas succeeds, its economy provides moderate prosperity to many. When Silicon Valley succeeds, its economy provides extreme prosperity to a few. By either measure, though, the eastern heartland has fallen behind. The region’s population growth is far less than that of the coasts, and its income growth is lower than that of the western heartland.

Perhaps the most disturbing gap between the regions is in mortality. In 1970, the eastern heartland had the highest mortality rate and the western heartland the lowest. Until the early 1980s, the three regions moved in parallel, and then AIDS pushed mortality on the coasts upward. By the 1990s, mortality on the coasts was falling again and is now compatible with mortality in the western heartland. But the eastern heartland’s mortality rate is much higher than both, and slightly higher than it was in the mid-1980s. Rising death rates could reflect economic hopelessness, as Case and Deaton suggest. They certainly represent another indication of the misery that so often accompanies joblessness.

Two factors have shaped why the eastern heartland has performed so poorly, both in joblessness and in overall economic performance: human capital and political institutions. Education correlates strongly with economic success at the individual, national, and regional levels. Human capital is particularly valuable in enabling adaptation to new conditions. Seattle and Detroit were both once industrial hubs, but Seattle’s education base enabled it to reinvent itself for the information age. Detroit’s far lower education levels have made its postindustrial transition far more troubled.

The eastern heartland traditionally has had some of the lowest education levels in America. Farm states such as Iowa pioneered the American high school movement, and they also anticipated a post-agricultural world where children would need other skills. The eastern industrial states saw little need to educate children who were headed straight to the factory floor. The southern parts of the eastern heartland were the poorest parts of the Jim Crow South. They did a particularly lousy job of educating their African-American citizens, but their white schools were hardly educational exemplars. In the late 1970s, the share of adults in the western heartland with a college degree was about 25 percent—the same as the share in the coastal states. The eastern heartland lagged far behind. Since then, the coastal states have surged ahead.

The eastern heartland is also home to America’s most corrupt states, at least as measured by federal corruption charges against local officials. Mississippi and Louisiana are perpetual leaders in this category, but Illinois, Kentucky, and Tennessee also rank high among America’s most corrupt states. Corruption is often accompanied by excessive regulation, doubtless because fewer rules mean fewer opportunities for extorting bribes to look the other way. The eastern heartland has often taken the lead in mandating licensing for occupations such as opticians, which pose few public safety concerns. By contrast, the states of the western heartland have been more likely to adopt pro-business rules, such as right-to-work laws. Thomas Holmes’s work shows that such rules powerfully attracted industry after World War II.

Is there a simple explanation for the antibusiness institutions of the eastern heartland? Mancur Olson’s justly famous Rise and Decline of Nations argued that insiders tend to protect themselves by building institutions that penalize outsiders. Restaurants get food trucks banned; unions make it impossible, or at least difficult, for nonunionized companies. The eastern heartland developed earlier in the country’s history, so it had more insiders trying to prevent competition.

If this view is correct, America’s oldest cities—New York and Boston—should be particularly prone to insiderism and cronyism, and they are; yet they still succeed. New York’s enormous human capital base, legacy of entrepreneurship, and sheer scale have allowed it to thrive despite frequently problematic political institutions and regulations that handicap entrepreneurs. By contrast, much of the eastern heartland has neither strong education nor robust institutions, and it consequently suffers.

When President Lyndon B. Johnson visited Martin County, Kentucky, in 1964 to promote his War on Poverty, two reasonable approaches for solving Appalachia’s extreme deprivation existed. The first, championed by Johnson and John F. Kennedy, was to throw resources, such as transportation spending, at this depressed area and hope for an economic transformation. The second was to accept that Appalachia was terribly positioned for long-term success and to help its poorer residents move elsewhere.

Fifty years later, Martin County remains poor. Astoundingly, only 26 percent of the county’s men over the age of 16 have jobs. Yet despite low levels of employment, only 30 percent of the families in the county live in poverty, thanks to the safety net. Only 6.3 percent of the population in the county has a bachelor’s degree or higher, which suggests only modest prospects for success in a working world that strongly values education. With 50 years of hindsight, it seems clear that exit, not a hoped-for Martin County renaissance, was the more likely path to individual prosperity. If applied widely, that logic suggests that America should focus on enabling migration to rich areas rather than on strengthening poor areas.

But out-migration is slow, especially today. Moreover, the tendency of skilled people disproportionately to leave declining areas means that those areas will only get more troubled as they shrink. We cannot overrule the tides of regional evolution, but we can make decline less painful. In particular, we can structure our social policies to fight joblessness more aggressively where joblessness is most severe.

Those looking to boost employment have lots of tools to choose from, though these tend to be costly, whether financially or otherwise. Supporters of protectionism, for instance, are correct that tariffs on steel might save some jobs in the steel industry, but many jobs would be lost in the other industries that use steel, including construction. Customers ultimately pay for new tariffs.

Expanding public employment is another option—by spending on infrastructure, say. Yet in today’s economy, such projects are more likely to benefit skilled technicians than the currently nonemployed. And when such infrastructure is targeted toward high-joblessness areas, we risk getting the worst kinds of public boondoggles, like Detroit’s People Mover Monorail.

The most simple and direct way to fight joblessness is to make work pay more, both for individual workers and for employers, and to reduce the implicit tax on employment generated by social programs. University of Chicago economist Magne Mogstad found that when Norway let disabled workers keep more of their earnings, employment among this population increased significantly. The United States could reduce the effective tax on earnings of the disabled or the effective taxes that come from food stamps and housing vouchers.

Reducing the “tax” that social programs create on working inevitably means that some working people will also receive benefits from those programs. If the number of beneficiaries rises, the total costs of these social programs will also go up, unless we also reduce the core benefit level. To keep costs constant, the most natural approach is to offset a reduction in the tax on working with a reduction in the size of the benefit for those who don’t work.

We should also ask whether employment subsidies, such as the EITC, could do more for our legions of nonemployed men. Since 1975, and especially after 1986, the EITC has increased the returns for working, especially among single mothers. The benefits reach a maximum for families with two children and income of $14,000. Extensive studies have shown that the EITC boosted employment for single mothers, illustrating the power that incentives have to generate employment. But the EITC’s benefits are fairly negligible for childless households, and its structure will actually deter working by the second member of a lower-income household, since the first worker has assuredly earned the $14,000 maximum. Only a tiny number of long-term jobless men live with more than one child and a nonworking spouse, so the EITC does nothing for this group.

But it could. We could design an employment subsidy that effectively upped the wage for all workers. The aid could be given to the worker, as in the EITC, or paid to the firm. Standard economics suggests that some of this wage bonus will find its way to the worker, but it makes sense to encourage entrepreneurs to think more about ways to employ marginal employees. A wage bonus would be more expensive if it applied to every American worker earning less than, say, $25,000 per year, but the cost could be mitigated if the bonus applied only to workers reentering the labor market after a period of nonemployment or after serving in the army. It’s common sense, and more cost-effective, to target limited resources toward the most at-risk populations.

At the heart of every income-based social-welfare program is a trade-off: directing resources to needy Americans is vital, yet doing so also discourages work. In the case of food stamps and Section 8 housing vouchers, each program generates a 30 percent implicit tax on earnings, because program benefits drop by 30 cents with every dollar of earnings beyond a basic threshold. Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society programs and their successors have created a more humane society in many ways, and the material suffering in places like Martin County has diminished substantially, but these programs have also made it easier to subsist, jobless, year after year. Their generosity has abetted the rise of long-term nonemployment in regions like eastern Kentucky, which has less educational attainment and labor demand. These social programs have much less of an adverse impact on employment in high-skill, high-wage states. A social-insurance program that pays an individual $10,000 per year as long as he doesn’t work will do little to deter employment in Santa Clara County, California, where 74 percent of households earn more than $50,000 and the unemployment rate is just 3.2 percent—but it will have a major impact in Martin County, Kentucky, where 74 percent of households earn less than $50,000 and such a low percentage of adults over age 16 are employed.

A similar dynamic pertains to progressive calls, in cities like Seattle, San Francisco, and New York, for a much higher minimum wage. The work of economist Jacob Vigdor and others finds that this higher wage depresses low-wage employment in Seattle, but that city’s superhot local economy mitigated the negative impact. By contrast, a $13 minimum wage in Appalachia would surely destroy many of the area’s remaining discretionary jobs.

There is little need for a strong employment subsidy in Silicon Valley. Most workers getting such a bonus would probably be working, anyway. Employment subsidies will do the most good if they are targeted toward regions with high levels of joblessness. Employment subsidies for low-wage workers will not bring back a declining region, but they will help ensure that residents are less likely to be jobless. Spatial targeting also makes sense because we want employers to generate jobs. If we make the subsidies particularly strong in distressed areas, employers will be focused on providing employment in those areas, where joblessness, responds more to extra labor demand.

The great potential drawback for place-based policies is that they will encourage people to stay in distressed areas. Yet with the decline in American mobility, out-migration is less likely to be the solution, anyway. If the extra aid is structured around a job subsidy, at least we won’t be creating pockets of permanent joblessness, because people can get the subsidy only if they work.

If the employment subsidy is offset by cuts to other forms of local spending, there will be less risk of thinking that we can revitalize a moribund local economy. To offset extra employment subsidies in high-joblessness areas, we could cut highway spending in those regions, since much of low-density America is already well-endowed with roads relative to the level of demand. Medicare and Medicaid spending per enrollee is often higher in distressed states, too, despite low wage levels. Perhaps funding for employment subsidies could come from streamlining health spending. Money could be squeezed out of programs that deter employment, in states where employment is a problem, and moved into programs that encourage working.

What we must recognize is that joblessness is an American curse but one that afflicts some regions more than others. The impulse to fight inequality by giving more money to the unemployed through schemes like the Universal Basic Income is a chimera. The UBI and other like-minded programs will only make joblessness more severe and America more miserable. A few extra dollars are not as important as a sense of purpose and achievement. We should subsidize employment, not joblessness, and we should promote employment most strongly in areas where joblessness is most pervasive.

Top Photo: J.D. Pooley/Getty Images