Nut Country: Right-Wing Dallas and the Birth of the Southern Strategy, by Edward H. Miller (University of Chicago Press, 256 pp., $25)

In September 2015, a reported 20,000 people packed a basketball arena in downtown Dallas, Texas, for a rally hosted by developer-turned-showman-turned-presidential candidate Donald Trump. In his trademark firehose style, Trump promised to build a wall on the southern border, belittled the intelligence of the political class, and identified a “silent majority” of Americans as his base. Edward H. Miller would likely find Trump’s high-octane performance a throwback to an earlier Dallas, reminiscent of the city’s fervid 1960s political atmosphere. In Nut Country: Right-Wing Dallas and the Birth of the Southern Strategy, Miller tracks the rise of ultraconservatives in Dallas and argues that this cohort had an outsize influence on national politics.

The book’s title borrows a phrase coined by President John F. Kennedy. “We’re heading into nut country today,” he reportedly remarked to Jackie Kennedy before his fateful 1963 visit to Dallas. There was plenty to justify JFK’s characterization. Perhaps no other large American city at the time featured a higher concentration of prominent right-wingers. W.A. Criswell, leader of the First Baptist Church, offered a spiritual defense of segregation (he later recanted). Bruce Alger, the first Republican congressman to represent Dallas since Reconstruction, cast the lone vote against 1958’s school lunch program, denouncing it as “socialized milk.” General Edwin Walker, who lost a Democratic primary for Texas governor in 1962, had been pushed out of the military for promoting the John Birch Society to men under his command.

The alpha and omega of the hard Right, however, was the Dallas Morning News, which both fomented and reflected the radicalism of its home city. Anticipating the heated style of conservative talk radio, its editorials lambasted “gimmiecrats” for leading the nation “into European-style socialism,” fumed against an Earl Warren-led Supreme Court that had become a “Judicial Kremlin,” and mocked the “weak sisters”—a frequent epithet—of the Kennedy administration. The paper’s bombastic tone emanated from publisher E. M. “Ted” Dealey, who inherited the paper from his father and transformed it into a vehement anti-Communist organ. Dealey had a Trump-like penchant for insult and willingly delivered his brickbats in person. During a White House visit, for instance, he told Kennedy: “We need a man on horseback to lead this nation, and many people in Texas and the Southwest think that you are riding Caroline’s tricycle.”

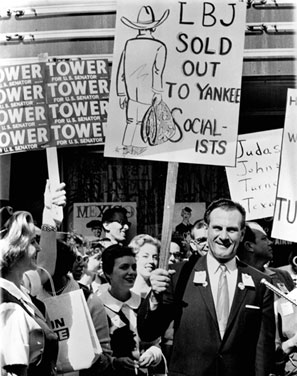

Opposition to Kennedy ran deep in Dallas, as his running mate Lyndon Johnson’s campaign visit to the Adolphus Hotel four days before the 1960 election showed. A sign-waving horde organized by Alger (who personally held a placard reading “LBJ Sold Out to Yankee Socialists”) confronted Johnson and his wife Lady Bird in the lobby, decrying the Texan as a traitor for joining a ticket headed by a supposed leftist and certified Easterner. Accounts differ about what transpired; some described it as little more than a peaceful, if energetic protest, whereas the Johnson crowd claimed to have been roughhoused and even spat upon. Regardless, Johnson, the consummate politico, exploited the situation for all it was worth, taking 30 minutes to walk from the hotel entrance to the elevators—reporters’ flashbulbs snapping all the way. The subsequent press photos seemed to depict the Johnsons enveloped by a sea of hostile protestors, and the coverage sparked sympathy for the vice-presidential nominee. Though the Kennedy-Johnson ticket ultimately won Texas by almost 50,000 votes, the incident cemented Dallas in the national psyche as a place where extremism flourished. Richard Nixon, Kennedy’s Republican opponent in 1960, believed that backlash from the protest cost him the state.

Miller ably sketches the colorful denizens of nut country but trips up when he turns to the the subject of his book’s subtitle—the oft-invoked Southern Strategy. In short, the strategy refers to Republican efforts to win the South by targeting white voters disenchanted with an increasingly leftward-tilting Democratic Party, particularly on civil rights. The GOP accomplished this, Miller argues, by appealing to white prejudice in the former Confederate states.

Without question, many politicians of all stripes made such appeals—GOP strategist Lee Atwater infamously admitted as much—but Miller paints with a very broad brush, detecting ill will in nearly every political utterance made by Republicans of the period. He contends that many Dallasites were “uncomfortable with overt racism” but nonetheless “susceptible to sophisticated encoded appeals to unacknowledged bigotry.” Thus, Republicans adopted the “color-blind language of justice for all” in wooing voters. Yet, Martin Luther King appealed to color-blindness as well, as did political allies like Johnson and Senator Everett Dirksen.

Miller’s argument becomes increasingly strained as he attempts to tie the book’s narrative to the present day. The post-2010 GOP, he claims, is “intransigent in its commitment to obstruct Obama’s inaugural call for ‘a new era of responsibility’ and post partisanship”—as if Republican resistance on policy matters like Obamacare or the federal debt stems from an aversion to bipartisanship rather than principled disagreement. All this Republican-created “gridlock,” Miller asserts, makes it “impossible to deal thoughtfully” with a host of pressing issues, such as “an emboldened Russia.” (Of all the criticisms hurled at congressional Republicans, the soft-on-Russia charge may be a first.) In one especially strange aside, Miller claims that birthers have “heartened” the Republican Party—ignoring how the Republican establishment has (rightfully) shunned these conspiracists.

Today’s “far right embraces absolutism and opposes any efforts to find middle ground,” Miller maintains. The same could be said of today’s far Left; amid all the breathless coverage of the tumultuous Republican primary, the media have devoted far less attention to Bernie Sanders, a self-declared socialist polling at levels not seen since the days of Eugene Debs. And ideological absolutism is hardly limited to one side: just ask the Brookings Institute scholar forced out by Senator Elizabeth Warren after having the temerity to suggest that some regulations actually impose costs.

Some parallels do exist between the era Miller chronicles and our present political culture—call it the Birchers-to-Birthers continuum. The “shrill rhetoric” he describes is mirrored by many ideological movements of today, and moderate and conservative elements of the Republican Party remain at loggerheads. True to form, Texas has provided some vivid demonstrations of that infighting, with the primary fight between David Dewhurst and Ted Cruz being one of the more recent examples. Thus, Miller’s book is both informative and timely. Too often, however, the author’s unsubstantiated political barbs mar an otherwise intriguing work.