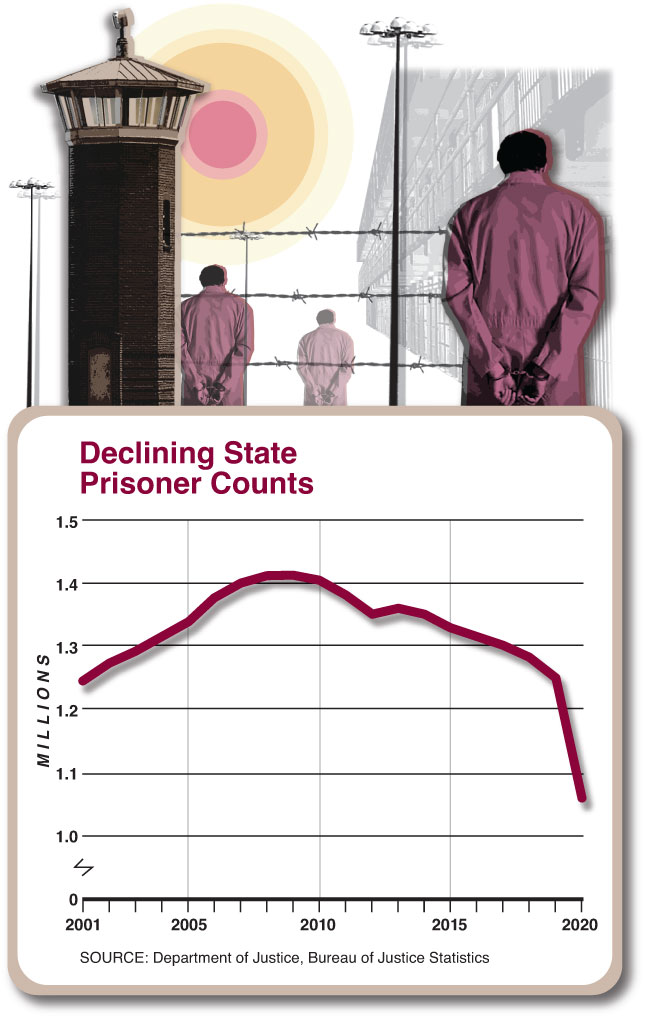

Since President Donald Trump signed the First Step Act in December 2018 to relax federal prison and sentencing laws, the federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) population has plummeted, reaching its lowest total since 2000. The federal government is not alone in trying to reduce confinement: several states have enacted reforms with this goal. According to Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) data, the American jail population declined 25 percent between 2019 and 2020; the jail incarceration rate is currently at its lowest point since 1990. During the same period, the state prisoner population is down 15 percent.

Animating these reforms is a belief that the United States incarcerates too many people and that prison is ineffective or unjust. Many academics, journalists, and activists criticize incarceration as unduly harsh on lawbreakers and corrosive to inner-city communities. Such organizations as the National Research Council of the National Academies, American Society of Criminology, and Academy of Criminal Justice Sciences have assailed the “systematic” and “entrenched” racism that allegedly characterizes our criminal-justice system. For many on the left, incarceration is simply a social evil. Some on the right also back such efforts, convinced that reducing prison populations will save tax dollars or that embracing reform will yield political benefits.

But mass incarceration is an ill-defined notion that ignores what we have learned about the essential role of government in controlling crime. Incarceration, appropriately applied, represents effective public policy, worthy of investment. Compelling data show that prison incarceration in the United States is lower than should be expected. While some states and public officials tout a hard line against crime, the reality is that many serious, recidivistic criminal offenders rarely see the inside of a prison cell. When they do, most get released after serving time well short of their actual sentence. Incarceration is the proverbial revolving door. Nevertheless, the mass incarceration narrative remains potent and retains bipartisan support—but its historical and empirical foundation is weak.

Contemporary reformists argue that rising incarceration rates in the late twentieth century represented a sinister attempt to reimpose a racial caste system after the end of Jim Crow. For much of the twentieth century, they say, despite increases in crime, new criminal statutes, and longer criminal sentences, prison populations and the amount of time served remained relatively unchanged—until the early 1960s, when politicians began to adopt tough-on-crime measures. Indeed, incarceration rates were low for much of the twentieth century, often not exceeding 150 per 100,000, at least using traditional methodology. Between 1880 and 1950, while the number of state prisons rose from 61 to 106, the U.S. population more than tripled, from about 50 million to about 152 million.

But incarceration was more common than this history lets on—and the eventual crackdown on crime, when it came, was long overdue. While incarceration rates seemed low in the early twentieth century, Progressive reformers also built a variety of institutions to detain the poor and infirm, the delinquent, the criminal, and the mentally ill. By 1940, almost 218,000 citizens 18 and older were in prisons, with another 99,000 in local jails and workhouses. And these numbers were far exceeded by the population housed in state mental institutions: more than 591,000, many of whom had committed criminal offenses. By 1950, that number rose to 613,000, with another 178,000 in state prisons, 86,000 in jails and workhouses, and 140,000 in youth facilities. Excluding the mentally handicapped, the total incarcerated population exceeded 1 million, for an incarceration rate of 670 per 100,000—far higher than the typically cited rate of that era of about 100 per 100,000.

As the deinstitutionalization movement targeted psychiatric prisons, individuals who had received treatment and other services in those facilities were set free. What deinstitutionalization advocates could not have forecast was the wave of social unrest and violent crime that emerged in the late 1960s and continued unabated for the next three decades. Yet state prison populations actually declined in the 1960s and early 1970s. There were 189,735 inmates in 1960 but only 176,403 inmates in 1970. “Proof is impossible,” noted William Stuntz in The Collapse of American Criminal Justice, “but the low and falling prison populations of the 1960s and early 1970s probably contributed to rising levels of serious crime during those years.”

As crime rose, the criminal-justice system was revealed to be pathetically underprepared. Limited training, inadequate equipment, and overt corruption plagued many police departments. In the correctional sphere, the number of jail cells and prison beds had not kept pace with population growth, much less with unparalleled increases in crime. Given the scarcity of correctional space, those arrested found themselves returned almost immediately to the streets, where most continued to re-offend.

The issue was not just one of resources. Sentences for serious crimes were brief. In 1933, a person convicted for murder or manslaughter would serve a median 44 months before release; by 1980, the figure had risen somewhat, to 60 months. The median time served for a rape conviction held steady at 36 months. And between 1923 and 1981, the median time served for all offenses fell from 18 months to 16 months.

To manage the growing numbers of people arrested for serious crimes, states began holding people bound for state prisons in local jails. In short order, local jails were overflowing with inmates, and many suits were brought for Eighth Amendment violations relating to overcrowding. States and local jurisdictions also started to manipulate the levers of confinement. Probation caseloads soared as courts diverted many offenders from prison while states simultaneously liberalized conditions for parole and good behavior. Revolving-door justice was born, not because of legislator contempt for public safety but because states had historically not adequately invested in their systems of justice—allocating resources to arrest, prosecute, and confine offenders—and thus were unprepared for how to handle a three-decade increase in serious crime.

“Mass incarceration is an ill-defined notion that ignores what we have learned about controlling crime.”

Increasing crime rates eventually became a federal issue. In 1968, Congress passed the Safe Streets Act, which created the Law Enforcement Assistance Administration, providing block grants for states and cities to improve police education and training, develop and increase funding of institutes for research and training, and expand jail and prison capacity. The new law emerged out of the recognition that investment in the justice system had not kept pace with population growth or crime. Before the Carter administration recommended the elimination of the block-grant program (and Congress agreed, in 1983), it would shift about $55 billion in inflation-adjusted dollars to the states to combat crime.

Federal funds encouraged states to modernize their justice systems, but jail and prison capacity still lagged year-over-year increases in crime until the early 1980s, when many states started funding new prison construction. In 1980, for example, the prison population rose by only 10,613. As more prison space was created through the 1980s, yearly admissions increased, reaching 75,521 in 1990 and approaching 80,000 in 1995. The size of the inmate population likewise grew, from more than 288,000 in 1980 to more than 1 million in 1990, and then to its 2009 apex of 1.4 million state prisoners.

If state spending on criminal justice increased dramatically after 1980, it was long overdue. As criminologist William Spelman notes, state spending also grew precipitously on education, parks and leisure, and health care as most state populations expanded. Hence, states were spending proportionately more on criminal justice, including on prisons, partly because they had spent so little on their justice systems for so long and because states now had more revenue to spend. Contrary to claims that incarceration is too expensive, the cost of housing state inmates has actually declined as a share of overall state revenues: in 1969, the cost was about 8 percent of all state revenues; today, that figure is just 2.9 percent.

This brief summary vitiates the historical arguments of today’s reformists. If mass incarceration ever existed, it was between 1930 and 1960. As crime worsened, governments were slow to react, getting a handle on the problem only well after the crime wave had begun. By then, however, the reformers who gave us institutions of confinement had turned against them, leaving millions of seriously mentally ill people to their own devices and then waging campaigns to reduce incarceration.

Reformists decrying mass incarceration don’t just advance a tendentious history. They also overlook four key facts about the contemporary state of the U.S. criminal-justice system. Both the prevalence of behavioral disorders linked with crime and the annual offending numbers conveyed by victim reports exceed incarceration rates, suggesting that the system has failed to capture a substantial portion of criminal offenders. The system also tends to be far more lenient than activists let on. Finally, the incapacitation of criminals itself offers public-safety benefits.

First, the prevalence problem. Behavioral disorders and pathological criminal prototypes linked with serious offenders are far more common than is incarceration. Over the past 40 years, the prevalence of prison confinement in the United States has ranged from 0.1 percent to 0.9 percent of the population. This pales next to the estimated prevalence of clinical psychopathy (1 percent), clinical antisocial personality disorder (3–4 percent), career criminality (5–6 percent), and life-course-persistent offending (10 percent). Extrapolating from these estimates, one suspects that many criminal psychopaths, career criminals, and offenders with lifelong conduct problems remain free to continue their offending careers. And data from nations spanning North America, South America, Europe, Asia, Africa, and Australia consistently validate the career-criminal prototype, the small group that accounts for more than half of the incidence of crime in a population.

Second, the annual offending problem. Each year in the United States since 1980, the FBI Uniform Crime Reports have counted 10–15 million arrests. The U.S. Department of Justice’s National Crime Victimization Survey has counted 20–42 million victimizations. Yet the total correctional population currently sits at 6.4 million, and the current prison confinement population at 1.47 million, for all offenders cumulatively sentenced over the past decades. Only a small fraction of the victimizations and arrests that occur annually culminate in a prison sentence—partly because of the incapacity of criminal-justice systems to process the magnitude of offending that occurs.

Reformists commonly lament the confinement of older prisoners, but the annual offending problem and the cumulative nature of the prisoner population counter such sentiment. A 2016 BJS report on the aging of the state prisoner population found that nearly one in three prisoners aged 65 and older was serving either a death or life sentence, and would never be released, barring exceptional circumstances. These would include multiple-homicide offenders; those who murdered while committing other grievous crimes such as kidnapping, rape, or armed robbery; and those who murdered police officers. Moreover, an aging prison population reflects not only the advanced age of the most recalcitrant offenders but also their ongoing annual offending. Between 1993 and 2013, the number of prisoners aged 55 and older admitted to state prison rose 400 percent.

Third, the leniency problem. Activist, media, and academic narratives suggest that scores of people are in prison for possessing small amounts of drugs for personal use, being unable to pay their fines and restitution, or perpetrating trivial technical violations of their felony probation or parole. Reformists assert a discriminatory process where offenders who are racial minorities face excessive confinement.

But the truth is that the justice system tends toward leniency. Offenders get plenty of opportunities for community-based supervision, have many of their charges dismissed or reduced, and recidivate frequently before actually being sentenced to prison. Nationally representative BJS data indicate that about one in four criminal cases—including nearly one in three violent criminal cases—is dismissed, and just 54 percent of violent offenses result in prison confinement. Most traffic, misdemeanor, and nonviolent felonies that end in conviction bring their perpetrators fines, restitution, deferred sentences, day reporting, home confinement, electronic monitoring, community service, or the ubiquitous probation. Less serious offenders comply well with these sanctions, complete their sentences, and exit the justice system, but even serious offenders receive these opportunities if their underlying charges are not grave. One example is Tom Latanowich, a 29-year-old probationer in Massachusetts who, in 2018, killed a police officer who was attempting to execute a warrant for his arrest. Latanowich had 111 prior offenses on his arrest record but received probation. His murder trial is ongoing.

Many arrest charges are dismissed, rejected in the interests of justice—meaning that the charges are considered too trivial to expend judicial resources—or are simply not prosecuted. In a population of federal correctional clients on supervised release after a term in federal prison, 36 percent of arrest charges in their criminal careers were dismissed. Are dismissed charges ipso facto evidence that the accused was wrongfully charged? In reality, most criminal charges are dismissed for triviality because the victim or witnesses in the case refuse to cooperate, or because the dropped charges were part of a plea agreement. A 2017 University of Chicago Crime Lab report found that in Chicago in 2016, only 26 percent of murders and 5 percent of shootings were cleared by arrest, and a troubling proportion of those did not result in conviction. The main reason for the low clearance and conviction rates was the unwillingness of victims and witnesses to cooperate with law enforcement and prosecutors.

The correctional domain is especially lenient. With important exceptions, most states and the federal system drastically reduce prison sentences via “good-time” reductions (such a provision was included in the First Step Act). Theoretically, these encourage rehabilitation, allow inmates to serve sentences concurrently, as opposed to consecutively, and impose post-conviction relief due to legislative changes. In practice, serious offenders often serve unserious sentences—undermining truth-in-sentencing and leading to miscarriages of justice. A 2021 BJS report found that the median time served in prison is 1.3 years. For violent crimes, the median is 2.4 years. For murder, the median is 17.5 years, with a mean of 17.8 years. Seventy percent of convicted homicide offenders serve less than 20 years before their initial release from state prison. And prisoners convicted of drug possession—the symbolic victims in the mass-incarceration myth—serve a median nine months in confinement before release. Serious offenders must busily engage in crime to climb the punishment ladder and receive a prison sentence, but once confined, irrespective of their conviction offense, they are soon released.

Finally, the incapacitation problem. Custody provides substantial public-safety benefits simply by incapacitating offenders. Increased incarceration through the 1980s and 1990s helped turn around the mounting levels of violence, though it was not the only factor involved. Studies find large reductions in crime attributed to earlier efforts to incapacitate criminal offenders. Consider, too, a recent BJS report on more than 404,000 state prisoners released from custody in 30 states. BJS found that 68 percent recidivate within three years and 79 percent within six years. For prisoners with the longest criminal histories, recidivism estimates exceed 80 percent. While a stint in prison may not deter future offending, the fact remains that incarcerated offenders can’t harm citizens.

Data also challenge the wisdom of conservative cases for decarceration. In November 2019, for instance, Oklahoma enacted the largest single-day prison commutation in U.S. history. Governor Kevin Stitt described the event as “another mark on our historic timeline as we move the needle in criminal justice reform, and my administration remains committed to working with Oklahomans to pursue bold change that will offer our fellow citizens a second chance while also keeping our communities and streets safe.” But while the Oklahoma Pardon and Parole Board recommended 527 inmates for commutation, 65 of those were wanted by another jurisdiction for criminal activity and could not be released. More than one in ten of these “non-violent, low-level offenders,” then, were ineligible for commutation because of the extensiveness of their criminal history. Among the 462 commuted prisoners released, 30 were back in custody by February 2020. That equates to an arrest rate of 6,494 per 100,000—more than double the national arrest rate of 3,011 per 100,000 in the United States.

The mass commutation saved $11.9 million from reduced confinement costs, equivalent to $25,758 per offender. How would those reduced prison costs compare with the per-offender costs of housing assistance, food vouchers, medical care, insurance, unemployment benefits, and substance-use treatment that are standard among inmates reentering society? How to value the public-safety threats arising from recidivism, which, BJS data make clear, is a near-certainty for most felony offenders?

In the final analysis, the U.S. incarceration system remains judicious. The narrative of mass incarceration fails on inspection. This is not to say that we should not question our use of prisons and jails—but a balanced and empirically informed approach would also question the likely consequences of incarcerating too few. The progressive Left remains unwilling to define the boundaries whereby crime reductions are maximized through confinement, or where too little incarceration increases crime and violence—as it has in recent American history, such as now.

The prison boom of previous years was the result of population growth, an explosion in crime and violence, and decades of neglecting our system of justice. When the volume of crime finally exceeded the system’s capacity to manage it, policymakers on the left and on the right responded to their constituents’ demands for public safety by investing broadly in our justice system: better-trained police, expanded probation departments, new intermediate sanctions—and newer, more efficient, and safer prisons. Through the combined efforts of police, prosecutors, judges, correctional officials, and legislatures, the crime surge was eventually blunted to unprecedented lows.

Under normal circumstances, these changes would be understood as the by-product of effective public policy. The wholesale rejection of incarceration as an effective policy tool risks too much. If past is prologue, then we can learn much from the consequences of deinstitutionalization and the failure to invest in all components of our justice system. Both led to more human suffering and to lives lost, as would current efforts to defund the police. We should avoid such mistakes and be reluctant to accept the kinds of promises that jeopardized public safety in an earlier era. “Hell,” wrote Hobbes, “is truth seen too late.”

Top Photo: America’s incarceration rate is currently at its lowest since 1990. (Eric Thayer/Getty Images)