Mahmoud Khalil—the green-card holder and Columbia-based Hamas sympathizer whom ICE detained last week—has overnight become a martyr for free speech. Advocates for his release, from Rep. Gerry Nadler and Sen. Chris Murphy to academic nonprofits, have framed Khalil’s detention as a violation of his speech rights. In this version of the story, he is an innocent campus protester caught up in the Trump administration’s crackdown on dissent.

These arguments don’t stand on firm First Amendment footing. As even the most Khalil-sympathetic legal scholars have acknowledged, the relevance of free-speech law in the case is at best unclear. Rather, as litigator Erielle Azerrad has explained, the case for Khalil’s deportation rests squarely on black-letter federal immigration law, and on the plausible threat that he posed to America’s foreign policy interests.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

But Khalil’s defenders are not interested in the particulars of either his actions or the law. Many appear to be following a straightforward syllogism: Khalil protested on campus; thus, he is participating in the grand tradition of campus protests and deserves not only protection, but celebration.

The notion that campus protests are intrinsically noble has been advanced by baby boomers since their college days. That assumption has provided cover for many heinous acts since the 1960s. While students do enjoy First Amendment protections, the uncritical veneration of campus protest often serves to protect dangerous radicals like Khalil. We can’t—and shouldn’t—change the Constitution to regulate campus protests, but we should regard them with far more suspicion than we do.

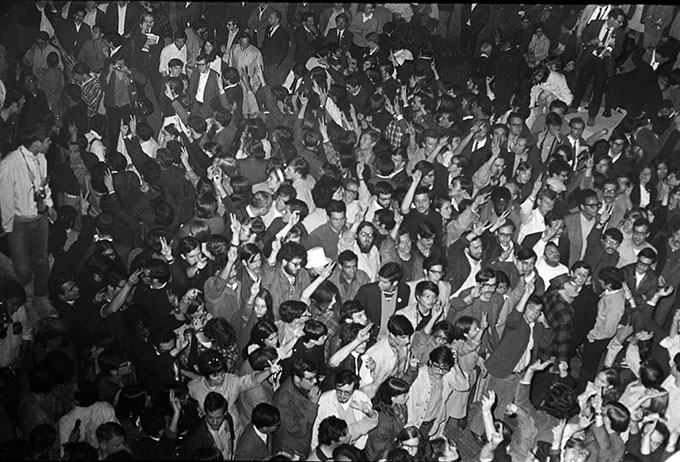

The campus protest paints a powerful picture in our collective imagination. Since the 1960s, marching, carrying signs, and sitting in have been perceived as a college kid’s rite of passage. We dismiss their excesses as the excesses of youth.

In Khalil’s case, the actual content of Columbia’s protests is wildly at odds with this benign picture. Students called routinely for “intifada, revolution,” invoking the violence in Israel that left more than 4,000 dead. Columbia University Apartheid Divest—the group that Khalil helped lead—identified with militants from the global South and called itself part of an insurgency. And multiple student radicals occupied the school’s Hamilton Hall.

Some may assume that this is a departure from the grand tradition of peaceful, law-abiding campus protest. In truth, the Columbia occupiers were taking a page out of their sixties predecessors’ playbook. In 1968, Columbia students occupied university buildings for almost a week before the NYPD forced them out. The next year at Cornell, black students, armed with guns and preparing for revolution, occupied Willard Straight Hall for a day and a half.

Back then, just as now, interference with other students’ lives was not merely permitted but encouraged. Students at San Francisco State University, led by the Third World Liberation Front, shut down the campus for five months amid a strike for an ethnic studies department. During Yale’s famous May Day protests in 1970, faculty won an unprecedented suspension of classes, as the entire university welcomed hundreds of outside radicals in a bid to prevent the protests from turning into riots.

Mainstream history often sanitizes these acts, but they shocked the contemporary public. When, for example, then-Yale president Kingman Brewster sided with his students’ anti-Vietnam actions, he attracted the near-universal ire of the college’s alumni. By the early 1970s, the only thing more unpopular than the Vietnam War were the students protesting it.

Khalil and friends’ tactics, in other words, are not a departure from the tradition of campus protest but a continuation of it.

The reason that such protests endure is straightforward. College campuses are full of the young and idealistic, whom professional activists are well-trained in manipulating. In his case study of Yale’s May Day protests, for instance, John Taft documents how the Black Panthers berated, cajoled, and pressured students into cautious pro-protest stances. When the organizers of Yale’s own encampment last year taught students to call for Intifada, they deployed the same tactics.

Maintaining the benign popular conception of campus protest is part of the hoodwink. As long as we agree that campus protests are generally praiseworthy, radicals will be able to hide behind that notion to advance their agenda. And when consequences come—as they have for Khalil—activists will use the popular notion of the innocent campus protester to avoid them.

The important thing, then, is to stop valorizing campus protests. College students have free speech rights—but so do Nazis and Communists. First Amendment protection is not grounds for approbation of all views.

In fact, we should regard the whole class of campus protesters with suspicion. College students have no special moral insight, and they are often dupes for well-funded, well-trained activists. That was as true in the 1960s as it is today.

Undoing the cult of campus protest would not merely correct such foolishness. It will also disempower the civil terrorists who occupy buildings, harass students, and pick fights with cops—then plead protester’s privilege when confronted.

Activists can keep selling this line, but Americans should stop buying it. People like Mahmoud Khalil aren’t heroes. They’re thugs who deserve the legal consequences they face. Their status as campus protesters should no longer be a shield behind which they can hide.

Top Photo by Robert Nickelsberg/Getty Images)