Aging middle-class Americans worry about retirement, and for good reason. The financial and economic crises of the last several years have left the country 10 percent poorer, obliterating $6.1 trillion in wealth, some of which people were saving for retirement. When the TV talking heads aren’t reminding us about plummeting house prices, they’re speculating about not whether, but by how much, politicians will cut Social Security and Medicare benefits. The baby-boom generation must wonder if it’s about to go bust.

The problems aren’t limited to the boomers themselves. As America ages, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid expenditures will inexorably rise, leaving less money for infrastructure, defense, and other important things. There’s also the risk that tens of millions of boomers, discovering that they haven’t saved enough money for their dotage, might all sell their assets at the same time and severely pare back their spending, plunging the economy not just into recession but into long-term stagnation.

Americans in their late forties through their early sixties shouldn’t stock up on cat food quite yet, though. Nor should we accept as inevitable a future in which the elderly consume so many public resources that they suppress growth for decades. Mass retirement will transform America, yes; and for some people, the transformation may be unpleasant. But it need not drag the nation under.

At first glance, the situation does look bleak: more retirees, less money. This year, the oldest of the 78 million babies born between 1946 and 1964 are turning 65 and becoming senior citizens. Because of the immense size of this baby-boom generation, the number of senior citizens will more than double between now and 2050, from 40 million to 89 million. And because the nation’s overall population will grow more slowly, older folks will make up an ever-larger share of it, increasing from 13 percent now to 20 percent in 2050.

Thanks to Botox and treadmills, the boomers are aging well. Their finances? Not so much, as some Federal Reserve numbers show. Baby boomers, like most Americans, have seen no wage gains for two decades. In 2007, families headed by younger boomers—those aged 45 through 54—earned a median income of $64,200, almost exactly the same, in inflation-adjusted dollars, as families in the same age group earned in 1989. (The comparison doesn’t work well for the older boomers—those aged 55 through 64—because, as we’ll see, people are retiring later these days, which skews their incomes.)

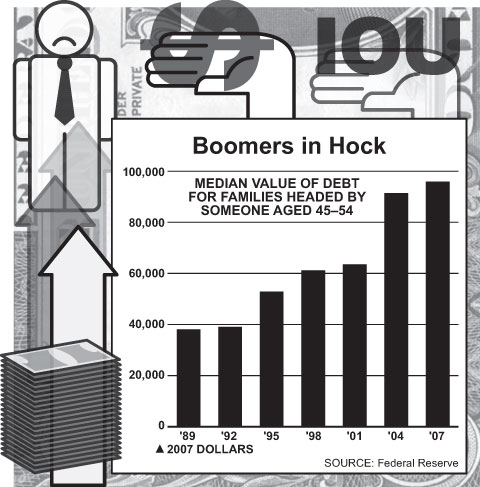

For years, boomers made up for their stagnant wages by borrowing, helping expand the credit bubble. Two decades ago, the average American family headed by someone in his late forties or early fifties owed $38,100, in 2007 dollars; by the time the global debt mania peaked in 2007, such families had more than doubled their indebtedness, to an average of $95,900. (All numbers in this story are adjusted for inflation, and this particular figure doesn’t include the 13 percent of such families that had no debt at all, a number that has remained fairly stable for 20 years.) Older boomers, too, dramatically increased their debt relative to earlier generations, from $15,400 in 1989 to $60,300 in 2007—and the percentage that didn’t owe money fell from 29 percent to 18 percent.

Everyone knows the chief culprit behind the debt explosion: mortgages. In 2007, the typical younger boomer family with a mortgage—66 percent of the group—was $110,000 in house-secured debt. That was nearly triple the amount that a similar family owed two decades earlier ($41,900). The average older boomer family with a mortgage, meanwhile, owed $85,000 in 2007, well over twice the $32,200 that the equivalent family owed in 1989. More older boomers, too, had mortgage debt: 55 percent, compared with 37 percent in 1989. Another sign that the boomers weren’t paying down their mortgages enough in preparation for retirement was that in 1989, 45-to-54-year-olds owed a full 35 percent less in mortgage debt than people a decade younger did. By 2007, the figure had fallen to 14 percent.

Until the real-estate bubble burst, middle-aged Americans told themselves that they were nurturing nest eggs, investments that would more than enable them to pay back what they owed. The facts seemed to bear them out: over the two decades leading up to 2007, the values of homes owned by people aged 45 to 54 exploded, rising 68 percent after inflation, to an average of $230,000. Older boomers made similar gains. Boomers also diligently socked away money in retirement accounts. By 2007, the two-thirds of younger boomers who had such accounts held $63,000 in them, on average; older boomers held $100,000.

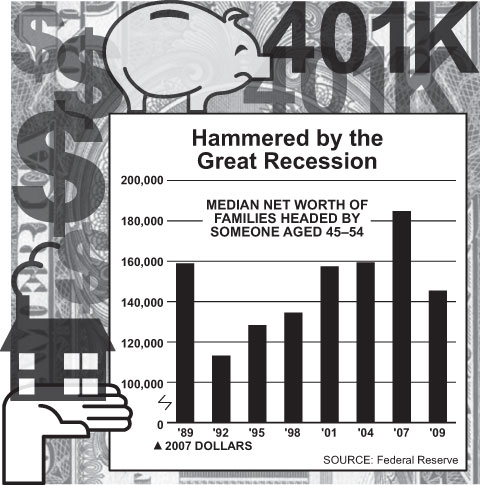

Thanks to the rising value of real estate and of stocks, younger boomers had managed, on the eve of the financial crisis, to amass an average net worth—assets minus debt—of $184,900, a modest but very real gain of 16 percent relative to their counterparts 20 years ago. Older boomers had $254,100, a striking 61 percent better than the previous generation.

By 2009, though, all of the younger boomers’ gains were gone. When their stock and house values crashed but their massive debt remained, younger boomers’ average wealth contracted to $145,400, 9 percent below what folks had two decades ago. Older boomers fared better, but still lost 15 percent, with their wealth shrinking to $214,800.

At first glance, that decline seems catastrophic. That $145,400, even if it grew 5 percent a year for another 20 years until retirement, would generate only the future equivalent of $15,400 in 2011 dollars in annual retirement income. As for older boomers, because they have much less time for their assets to grow, their current $214,800 would generate only about $14,000 a year in retirement income. True, older boomers are likelier to have corporate pensions to supplement their assets. But for most Americans, those sums would offer a bare subsistence, not a fulfilled existence—especially if politicians slashed Social Security, too, as conventional wisdom has long regarded as inevitable.

It’s no surprise, then, that folks feel queasy about their retirement prospects. The Employee Benefit Research Institute (EBRI) conducts an annual survey, sponsored largely by financial groups, to quantify this unease. The 2011 edition found that “Americans’ confidence in their ability to afford a comfortable retirement has plunged to a new low.” Half of workers of all ages were “not at all confident” or “not too confident” that they could save enough before they stopped working, up from 29 percent in 2007, before the financial crisis. Of people aged 45 through 54, 29 percent lacked any confidence in their retirement prospects, more than double the 11 percent similarly worried in 2007.

Part of the solution to the retirement crisis is to shorten the years of retirement. “Working longer is the key to a secure retirement for the vast majority of older Americans,” notes Alicia Munnell, a Boston College management prof and director of the school’s retirement-research center. If you’re working, you’re not consuming your savings as much; in the best case, you’re still adding to them.

The idea of working until the end—or closer to it—isn’t new. Many of today’s retirees have enjoyed decades of relaxation financed by company pensions and Social Security, but for most of history, voluntary retirement was the exception, not the rule. “Up to the end of the nineteenth century, people generally worked as long as they could,” Munnell writes. “At the end of their lives, they had only about two years of ‘retirement,’ often due to ill health.”

As the century turned, however, more Americans began to enjoy leisure time before they died. Many older couples survived on Civil War veterans’ pensions and, beginning in 1935, on welfare benefits for the elderly, followed by Social Security. After World War II, companies began to lure and keep workers by providing them with pensions, which often encouraged workers to retire before 65, notes Jack VanDerhei, director of research at EBRI. Responding to such signals, twentieth-century workers got used to the idea of retiring.

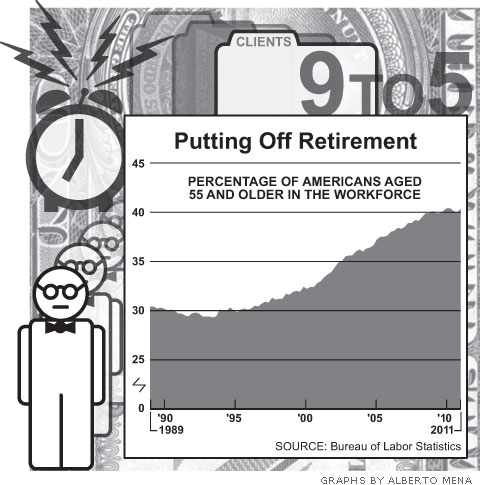

But a reversal began in the 1980s, as retirement ages for men started to rise. Men today retire at 64, on average, up from 62 two decades ago, Munnell has found. (Women now retire at 62, but comparisons with previous eras are tricky, since back then, most married women didn’t work throughout their lives.) In 2010, according to the U.S. Census, 62 percent of men aged 60 to 64 were either working or looking for work, a significant increase from 56 percent a decade before. Among men 65 and older, 22 percent were in the labor force, up from 16 percent a decade earlier. The change shows up in Social Security statistics, too. Social Security lets people retire as early as 62, but to get full benefits, you have to be a few years older. By the mid-2000s, more than 20 percent of men were delaying collecting until they had reached full retirement age, up from 17 percent in the mid-eighties. For women, the figure had moved from 12 percent to 16 percent.

Washington is partly responsible for the shift. Nearly three decades ago, President Reagan and the Democratic Congress enacted a law that gradually increased the age at which people could retire and get full benefits, from 65 at the time to 67 in 2027. People retiring this year, for example, must be 66 to receive full benefits—though a Nixon-era change gives them even higher benefits if they wait until 70. In 2000, President Clinton and the Republican Congress added a further encouragement to work longer, repealing a hefty tax slapped on those who chose to keep working while collecting Social Security, as long as they waited until the full retirement age to collect.

The corporate world, too, has contributed to people’s retiring later, though in a different way: moving from guaranteed lifetime pensions, based on workers’ salaries, to matching employees’ own retirement savings. That encourages people to work longer. In 1980, when the baby boomers were young, 60 percent of private-sector workers with retirement plans could rely on guaranteed employer pensions. A decade later, the figure was down to less than a third; today, it is 7 percent. (That doesn’t include the 22 million Americans who work for government, many of whom will receive pensions when they retire.)

So far, people have changed their behavior only gradually. But as those who have received the new signals during their entire working lives approach traditional retirement age, it’s probable that more and more of them will keep working. Making that outcome even more likely, baby boomers have absorbed the cultural lesson that idleness isn’t a good thing, often from watching their parents stagnate in long retirements. “We don’t believe we’re reaching retirement age,” says Hershel Chicowitz, who runs the Baby Boomer Headquarters website and newsletter. Chicowitz thinks that many boomers will just “keep working” or start second careers as they enter “old age.” The 2011 EBRI survey backs him up: 36 percent of the respondents figured that they’d retire later than 65, a jump from 25 percent in 2006 and more than three times the 11 percent figure of 1991. Three-quarters of those surveyed said that they’d work at least part-time after “retiring.”

Most people can work for a few more years, maybe even a decade, but they can’t work forever. Barely a quarter of those aged 65 to 74 were in the workforce last year, according to the census. The number declines precipitously as you get into even older age groups, to less than 9 percent of those aged 75 to 84 and less than 3 percent of the 85-and-up bracket. There’s no way around it: baby boomers will eventually have to retire, and to do that, they’ll need more savings than they’ve managed to accumulate.

This isn’t to say that they won’t have any income from Social Security, as some politicians and pundits have warned. “As far back as I can remember, people said, ‘Don’t count on Social Security; it will be gone,’ ” says Chicowitz. Indeed, a full 87 percent of workers told EBRI last year that they feared Social Security cuts.

But the situation isn’t quite that dire. For decades—until last year—workers paid more into Social Security than retirees took out. That “trust fund” of extra money, amounting to $2.6 trillion, went into a big pile of IOUs from the U.S. Treasury, helping the government spend money on everything besides Social Security, from food stamps to national defense. Now, Social Security’s annual surpluses are turning into deficits. To finance the annual deficits, the system this year is turning to its trust fund. But it will take a long time to exhaust the reserves: the trust fund won’t run dry until 2037, when the youngest boomer is 73.

At that point, if nobody has acted to reform Social Security, a 24 percent reduction in benefits would kick in automatically. But some kind of reform is almost certain. After all, those millions of boomers vote, making it highly doubtful that Washington would close the Social Security deficit entirely through slashing benefits. Even raising the “early” retirement age is unlikely. If politicians were going to do that, they would have done it in 1983, when the boomers were still young. Making such a move now would provoke well-founded complaints that mandating a longer work life, rather than merely encouraging it through incentives, would unfairly harm workers who have done heavy labor all their lives.

Reform isn’t the impossible task that it seems, either. Henry Aaron, the Brookings Institution’s Social Security guru, estimates that over the next 75 years, Social Security will take in about 14 percent of payroll and send out about 16 percent. “Minor adjustments are sufficient to close the funding gap,” he says. Of course, as Social Security lends less and less to the Treasury, that will create a problem for the rest of the government, which will find itself with a lot less money. But as Aaron also notes—and as the Standard & Poor’s August downgrade of the U.S. credit rating reminded voters—Washington must confront that fiscal issue long before 2037. As Alan Glickstein, a senior retirement consultant at benefits consultancy Towers Watson, sums up: incremental reforms will probably continue to modify Social Security, “but it will still exist and be recognizable in its current form.”

Social Security will get poorer Americans “a good chunk of the way there” in replacing preretirement income, observes Glickstein—up to 90 percent of it for some retirees. But middle-class workers can’t rely on Social Security to replace anywhere near their preretirement income. Social Security replaces only about a third of earnings for retirees who made $55,000 a year, with the figure falling to 15 percent for high-five-figure earners. If Americans don’t save and invest enough today, it could mean smashed dreams tomorrow—as well as deflation for the broader economy, as tens of millions retreat from consumption.

But “there doesn’t have to be a crisis,” says Michael Falcon, head of retirement at J. P. Morgan Asset Management for the United States and Canada. Generally, Falcon says, a retiree will need an annual income that’s 80 percent of his preretirement income. He adds that frequently “we see a U shape,” with people spending lots of money in their early retirement on exotic trips, less as they get older and less adventurous, and then, as they get really old, lots of money again on health care.

Hitting that 80 percent mark isn’t impossible, but it’s certainly daunting. Recall that in 2007, the average family headed by younger boomers earned $64,200. In retirement, such a couple will need 80 percent of that per year—roughly $51,400. They’ll get about $17,500 from Social Security if they stop working at 62, or $24,900 if they wait until 67. That leaves a gap of $26,500 to $33,900. But remember, even after the market crash of 2008, the average younger boomer family had $145,400 in net worth. If those assets grow by 5 percent annually for another two decades, until they retire, the couple will make up for about half of the gap.

Can they come up with the remaining $15,000 or so? Retiring much later would help, with Social Security providing $30,900 a year for those waiting until 70—an extra $6,000 annually above retirement at 67. Some boomers will have additional income from a traditional pension, though many of these accounts are modest, as companies started freezing their contributions to such plans more than two decades ago. For people without such pensions, the answer, even if it’s only a partial one, is to save as much as possible while they’re still working. Falcon says that workers should be saving and investing a minimum of 10 percent, and perhaps as much as 14 percent, of their pretax income. Vanguard, the mutual-fund giant, recommends 12 to 15 percent. Americans currently save only about 5 percent—up from the near-zero levels of half a decade ago but still nowhere near enough. Vanguard notes that, including employer matches, the average participant in the 401(k) plans that it administers for employers contributes only about 9 percent of his income, and that only about one-third of its participants presently meet its suggested investment threshold.

Additional saving may not close the entire gap. But it can turn a catastrophic decline in living standards into a smaller adjustment. Of course, looking at averages this way ignores the worst-off—in this case, the millions of boomers who have saved nothing at all. It’s growing rather late for them.

Washington has already taken modest steps toward encouraging people to save more. In 2006, President George W. Bush signed a law that allowed employers to enroll workers in 401(k) plans automatically, so long as they didn’t specifically opt out. “It’s one of the best things Congress has done” to increase 401(k) participation, says VanDerhei of EBRI. Vanguard says that the change has led more people who earn less than $30,000, in particular, to invest.

The nation needs a more dramatic shift from spending and borrowing to saving and investing, however. Here, the pols can use the tax code as a signal. Right now, people can contribute only $5,000 a year before taxes to personal-retirement accounts outside their employer plans—a ridiculously low amount. The government should invite people to save all they can, eliminating the annual limit and imposing only a lifetime limit of $1 million. Those who don’t like the 401(k) plans that their employers provide or simply want to save more outside those plans would then have a substantive choice. The president and Congress should also eliminate capital-gains, dividends, and interest taxes on anyone, say, earning less than $250,000 a year, since these taxes discourage people from investing.

Washington must be sure, though, not to encourage everyone to invest in the same thing simultaneously, as happened during the Clinton era, when the government eliminated capital-gains taxes on home sales for middle-class earners but not on any other types of investments. If everyone buys the same thing, its price goes so high that eventually it has to crash. The Bush administration’s 2006 pension-reform law is troubling in this regard, by the way, since it favors the “target-date fund,” through which investors “target” the year they’d like to retire and let investment managers choose a mix of stocks, bonds, and other assets based on that date. Such funds can be a useful tool, but with so many boomers expecting to retire on the same target date, there’s a real risk that fund managers will find themselves buying and selling the same classes of securities simultaneously.

Workers need to invest more but also need to earn better returns. In fact, an 8 percent return on existing investments, rather than 5 percent, would solve much of the problem for younger boomers. It’s good news, then, that the average 401(k) investor has stuck to stocks, even though they’ve had a bad decade. As of 2010, Vanguard points out, its investors aged 45 to 54 had 73 percent of their accounts in stock or the stock portions of mixed funds; for 55-to-64-year-old investors, the figure was 61 percent. Those numbers have stayed pretty much the same since the financial crisis began, meaning that people have largely done what they’re supposed to do during times of upheaval, which is not to panic and sell. Vanguard chalks up some of the sanguinity to middle-aged investors’ memories of the 1983–2000 bull market: they believe that gains are possible if they sit tight.

If the government simply stuck with shoring up Social Security and modifying the tax code to encourage investment, and avoided getting heavily involved in other areas of retirement, retirees would likely benefit. Grown more confident that Social Security would always be their fallback, Americans might be more willing to invest their other retirement money, even after they’ve stopped working, and thus create additional income for themselves.

The biggest unknowable risk for future retirees is health care. VanDerhei notes that if you take health costs into account, a retiree may need not 80 percent of his preretirement income but more than 100 percent of it. The problem isn’t so much regular or even catastrophic costs, which Medicare and supplementary insurance cover. It’s long-term care: nursing homes for the elderly with dementia, for example, and in-home care for people whose frailty keeps them from caring for themselves. Medicare does not cover such costs; Medicaid does. But Medicaid requires its beneficiaries to be, practically speaking, poor. Of course, you will be poor after shelling out for a nursing home for a while—but so will your surviving spouse, who will have to live in severely straitened circumstances for the rest of his or her life.

If you look hard enough, you can purchase long-term care insurance while you’re still young and healthy. It’s expensive, though, partly because insurance companies are suspicious of their customers, recognizing that those who buy this protection probably have a reason for it. Someone who knows that his parents spent a long time in nursing homes, for example, is more likely to buy care insurance than someone whose parents were healthy until the end.

Potential customers return the suspicion. As three National Bureau of Economic Research fellows determined in a recent paper, many Americans fear that they could spend money on insurance premiums for long-term care, only to watch the insurance companies go bust 20 years down the road. “As events during the recent recession illustrate, long-term contracts are not always honored,” the authors write. “The risk of insurance companies going bankrupt . . . may be [a] reason why demand for long-term care insurance is limited.” One reasonable-sounding solution would be for the government to guarantee such contracts. Yet the logical way to do it would be folding them into the government’s own insurance program, Medicare, which would require raising Medicare premiums significantly. For the time being, that’s a political nonstarter.

The best thing for now may be to take advantage of the fact that Medicaid is a state-administered program and to encourage states to experiment more. Congress should reward states that save money and improve treatment, perhaps allowing someone who cares for an infirm spouse to purchase care directly, aided by a government matching sum. Such reforms may be inevitable, in fact, since it’s impossible for almost any retiree to make over 100 percent of his preretirement income. Moreover, the boomers are likely to resist bankrupting themselves for miserable care. “I don’t see the boomer generation sitting in some nursing home,” says Chicowitz. As demand for long-term care changes, supply will have to change, too.

America has significant retirement problems, but we may still be better off than the rest of the world. “The U.S. challenge of financing the transition of the baby boomers into retirement is modest compared to the demographic challenge faced by most other high-income countries,” write Brookings scholars Barry Bosworth and Kent Weaver in a recent paper. Though our proportion of the working-aged to the retired will decrease, the fall will be less dramatic than in other developed countries. The nation in 2030 will have 204 million citizens of working age—still nearly three times the number of those 65 and older.

Whatever happens, it’s not going to be the static crisis that spreadsheets would predict. As the boomers were born, they sparked the construction not just of homes but of entire towns and school districts; as they went to work, they created day-care centers for their children. As they age, they’ll surely continue to change the economy, though the effects are hard to predict. When boomers exchange their bigger houses for smaller ones, house prices may fall even more than they already have, helping younger Americans to use their own savings more productively and generating more wealth. When boomers leave the workforce, wages for younger people may rise, pressuring supply to keep up with demand. Retirees may support younger generations—just as the homemakers who stayed out of the workforce half a century ago contributed to the economy with their unpaid labor—by babysitting their grandchildren, freeing up mothers to work and perhaps encouraging higher fertility. Instead of selling their homes, boomers may invite younger generations to come live with them.

The most disturbing statistic on older-worker employment is this: in 2010, only 77.6 percent of men 55 to 59 years old were working or looking for work—down from 78.5 percent in 2007 and 79.1 percent in 1999. Hammered by the slumping economy, late-middle-aged folks have increasingly dropped out of the workforce and waited to start collecting Social Security. In 2009, only 14 percent of new male Social Security beneficiaries were of “full retirement age”—a precipitous fall from the 26 percent figure of the previous year. It was the lowest rate ever. Unless older unemployed people get back to work soon, they’ll never go back, and they’ll become poorer retirees than they needed to be.

What this means is that fixing our economy now is the most important task of all. Let the housing market find its bottom, so that people who want to cut losses on bad housing debt have the information they need to make such a momentous decision. Invest massively in infrastructure. Fix the tax code to channel money out of debt and into innovation. Fix immigration so that we continue to attract the world’s smartest people. These measures would get people back to work soon and prepare the nation better for the future, making it likelier that those who will shoulder the burden of caring for an aging population are able to do it.

Top photo: sompong liabsanthia/iStock