Theodor Geisel’s Dr. Seuss books are so popular, and printed and reprinted in so many editions, that you can find used copies of classics like The Cat in the Hat on eBay.com for under $5—shipping included. You can typically even snap up a first edition of something like Hooray for Diffendoofer Day! for just $4.99, plus $3.45 shipping. Yet on Tuesday, sellers suddenly inundated eBay.com with new, pricey Seuss listings. A 1964 edition of And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street went onto the site at an astonishing $400!

Though that sounded expensive, within an hour some 140 would-be sellers had examined the listing. A newer, less prestigious Grolier Book Club edition of the same book was offered for a more modest $80. By 11:30 Tuesday morning, someone had already snapped it up. The buyer must have considered himself fortunate, because by noon a similar edition of the book had already received 17 offers, in the process getting bid up to $127, with four days left to go in the auction. Potentially the biggest jackpot of the day, however, would go to the person listing an edition of 13 stories of Dr. Seuss, all packaged together. Several hours and 20 bids later, the price had hit $162, with six days of bidding left.

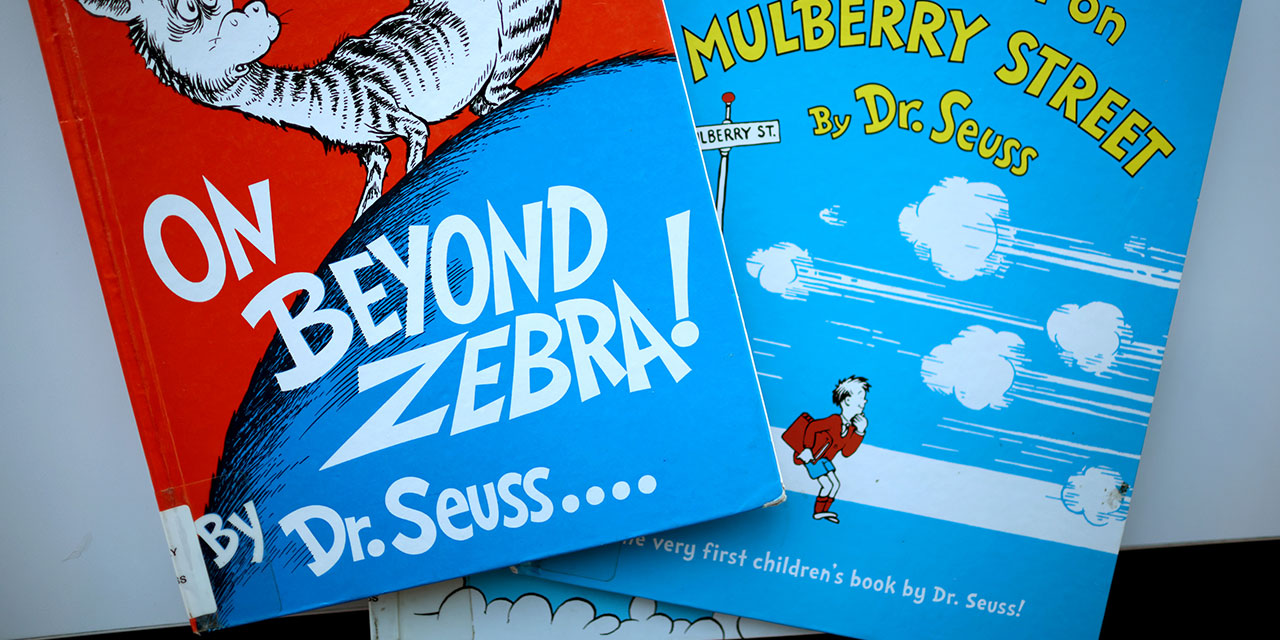

Book collectors are an enterprising lot. The sudden online Seuss surge was the result of news that Geisel’s descendants, who have controlled the rights to his books since his death in 1991, had decided to stop publishing six of his titles (Mulberry Street, If I Ran the Zoo, McElligot’s Pool, On Beyond Zebra!, Scrambled Eggs Super!, and The Cat’s Quizzer) because critics allege that they contain racist or insensitive imagery. An academic journal, Research on Diversity in Youth Literature, has even accused Geisel of white supremacy for a “preponderant influence or authority demonstrated by White characters over others” in his books and for Orientalism, defined as distorting “differences between Middle Eastern, Southeast Asians, South Asians, and East Asians” and portraying these “cultures as exotic, backward, uncivilized.”

It’s hard to know what was more shocking: that the beloved Seuss and his seemingly innocent narratives had become the subject of the cancellation cult, or that there was a journal apparently devoted to ferreting out racist imagery in children’s books. The books haven’t exactly been hiding somewhere, unread. Publishers have sold an estimated 600 million copies of Seuss, many of them presumably read by parents, teachers, librarians, and assorted other educated and tolerant people over many decades and lauded by prominent politicians, including Barack Obama and Kamala Harris. It took a peer-reviewed academic journal to persuade us—or at least to persuade Geisel’s family—that the children’s book master was in fact a bad influence. (Not missing a beat, the Biden administration subsequently declined to mention the author’s books on Read Across America Day, held annually on Geisel’s birthday.)

One irony of this latest cancel-culture episode is that Geisel himself was a man of the Left, a progressive who opposed fascism, decried “red baiting” in the 1950s, and devoted an entire book to educating kids about the budding environmental movement of the early 1970s, as described in a 2011 article, “Dr. Seuss’s Progressive Politics.” With the outbreak of World War II, Geisel even put aside writing children’s books and worked as an editorial cartoonist for PM, a liberal New York newspaper published during the war and noteworthy for refusing to accept advertising so as not to compromise its values. Geisel’s cartoons from that era revealed a man who vigorously opposed fascism, steadfastly supported Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s prosecution of the war, and lambasted the president’s congressional opponents, especially Republicans.

When Geisel resumed writing children’s books after the war, it was with an eye toward shaping young minds. As entertaining as the Seuss books are, you don’t need to be a literary critic to see the messages in many of them. Horton Hears a Who!, a book about an elephant who persuades his neighbors to protect a small, vulnerable group of people known as the Whos, is seen as a “parable about protecting minority rights,” a plausible reading of a book by a man who, in a 1947 university lecture, urged writers to avoid racist stereotypes. In Yertle the Turtle, an arrogant king of his local pond is indifferent to the suffering of his subjects, who complain, “I know up on top / You are seeing great sights / But down at the bottom / We, too, should have rights.” The Lorax, adapted by Hollywood as both a TV series and a movie, tells the story of the Once-ler, a creature who finds and cuts down a precious tree to sell and is warned by the Lorax, who “speaks for the trees,” of the consequences of a business built on using up natural resources. Geisel himself called the book, published in 1971 in the wake of the first Earth Day, “propaganda.”

Not surprisingly, social media became a battleground over the family’s decision to cancel the six Seuss books. One defender of the move said that it was time for critics to “evolve.” But Geisel has hardly had that opportunity himself. The academic attack on him in Research on Diversity in Youth Literature includes a section on cartoons he published during his college years in the 1920s deemed anti-Semitic and anti-black. It apparently counts for nothing that, for the rest of his life, he pursued progressive causes, decried the targeting of Jews in Germany, criticized the segregationist policies of the U.S. armed forces during World War II, and became an early supporter of the Civil Rights Movement. The Geisel episode is further evidence that, these days, anything remotely suggesting an unacceptable opinion by twenty-first-century standards, issued at any point in an artist’s life, is sufficient cause for cancellation.

In a sensible world, Geisel’s heirs would leave it to parents, educators, and librarians to determine whether Dr. Seuss books should remain available to kids. After all, it’s not as if five-year-olds are logging onto eBay and ordering copies of And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street on their own—especially not at today’s prices.

Photo Illustration by Scott Olson/Getty Images