I know the American People are much attached to their Government,” Abraham Lincoln said in his Lyceum Address of January 1838, when he was a rising, almost-29-year-old state politician in Illinois. Curiously, American government was itself just shy of 62 years old, which, in politics, is not a long time for attachments to develop. The United States had no long descent to trace from toga-draped elders; it had no official language, no state church, and no national university. It was built around a Declaration and a Constitution whose creators were guided by what they had read in a dozen or so treatises of Enlightenment political theory. By all traditional understandings of government, the American republic should have been impossible. The reactionary Frenchman Joseph de Maistre sneered that “the government of a nation is no more its own work than its language” and cannot “be made as a watchmaker makes a watch.”

Still more dubious, the government that the Constitution mandated was to be a republic with a strong pull toward democracy—exactly the kind of government that in classical history was admired for its nobility but pitied for its fragility and that had never worked effectively, except in small-scale, face-to-face environments. And the 13 former British colonies that established their independence as American states would be joined together only as a federal union. “It will not be an easy matter to bring the American States to act as a nation,” predicted the Earl of Sheffield in 1784. “We might as reasonably dread the effects of combinations among the German as among the American States.” Even our allies agreed: “In all the American provinces,” wrote France’s chargé d’affaires in America in 1787, there will be “little stability.”

Sure enough, the republic fractured within three decades into rival political parties, suffered through two serious outbreaks of conspiracy and rebellion (the Whiskey Rebellion of 1794 and Aaron Burr’s 1805–06 plot to set up his own private fiefdom in the Mississippi River Valley), blundered into a near-fatal war with Great Britain in 1812, and then endured the economic panic of 1819. Political life seemed to grow rowdier with every decade. Members of Congress brawled on the floor of the House of Representatives. Elections were riotous affairs where voters were “open to the promptings of every rascally agitator,” where threats and intimidation turned away “numbers of native-born citizens,” like the Baltimore lawyer in 1860 who “would say they had wives and children, and would not like to risk their lives in a useless attempt,” and where the indifferent jackanapes denounced by Francis Parkman “cares not a farthing for the general good” and “will sell his vote for a dollar.”

But far from this proving to them the folly of their government, Americans believed in it with an almost religious reverence. They did not merely create a republic; they created a highly democratic one, absorbing the democratic principle into their pores. “There is no such thing as class distinction here,” wrote a Swedish immigrant in 1846, “no counts, barons, lords or lordly estates. . . . Neither is my cap worn out from lifting it in the presence of gentlemen.” The democratic citizen, wrote novelist James Fenimore Cooper, “insists on his independence and an entire freedom of opinion.”

No one understood Americans’ devotion to their democracy or shared it more thoroughly than Lincoln. For the safekeeping of their democracy, Americans “would suffer much for its sake. I know they would endure evils long and patiently, before they would ever think of exchanging it for another.” Certainly, he would. “We have the best Government the world ever knew,” Lincoln told a newly recruited regiment of New Yorkers 26 years later—a government in which “the people” had the “right to decide the question,” whatever the question might be. And it was one that he was happy to share as broadly as possible: when “I see a people borne down by the weight of their shackles—the oppression of tyranny . . . rather would I do all in my power to raise the yoke, than to add anything that would tend to crush them.”

This was not because Lincoln had no eye for Americans’ political excesses. But what mitigated the baleful tendency of passion in democracy was law. In one American law treatise and discourse after another in the 50 years after independence, the law was held up as “a moral science of great sublimity,” wrote Baltimore jurist David Hoffman in 1817; it was nothing less, said the Irish exile William Sampson, than “the public reason, uttered by the public voice.” The vocation of the lawyer, then, was (according to Hoffman) “the conservation of the rights and prosperity of the citizen, and the vigorous maintenance of the legitimate and wholesome powers of government,” while the responsibility of “the good citizen” was “to love the laws, and . . . to obey them.” Aristocracies were “governments of will”; democracies were “governments of law.” So long as Americans allowed themselves to be ruled by reason, they would choose to be ruled by law, and all would eventually be well with their democracy. But if Americans should surrender to “the dictates of passion and venality, rather than of reason and of right,” warned Brown University president Francis Wayland, at “that moment . . . will the world’s last hope be extinguished, and darkness brood for ages over the whole human race.” Even democratic government’s most reckless champion, Andrew Jackson, was—at least at first—a lawyer. The man who proposed to save it from Jacksonian passion—Abraham Lincoln—was a lawyer, too.

In 1828, Andrew Jackson won his second bid for the presidency and rode to power the following March as the champion of the Democratic Party and “the direct representative of the American people,” one who would be “responsible to them” rather than to the legislative and judicial branches of the federal government. With that mandate, Jackson’s two terms as president wrought calculated havoc on the nation’s bankers and banking system, expelled Indian tribes from their homelands, and turned presidential appointments into a “spoils system,” all while he positioned himself as the people’s tribune. He was the first singular example of what James Madison most feared from democracy: a weakness for demagogues who would play to fear, anger, and contempt, and persuade Americans to put more faith in power than in liberty.

Jackson left office in 1837, just in time for the nation’s economy to collapse into another financial panic. “At no period in its history has there been as great a degree of general distress as there is at this day,” wailed a short-lived New York Democratic newspaper. “Of its mechanics and other working men, at least 10,000 are without employment, and their wives and families . . . are suffering . . . heart-rending want.” Want kindled fury, and not just over the economy. More than 140 riots erupted, and mob violence in Boston, Philadelphia, and New York overran businesses, struck out at landlords, “monopolists and extortioners,” and targeted white abolitionists and free blacks, who looked like a source of labor competition. In New York, “a mob of several hundred” ransacked merchants’ warehouses for flour. William Ellery Channing, addressing a convention of the American Anti-Slavery Society, was attacked with “repeated showers of stones and rotten eggs.” What had been “a government of laws,” complained Channing, now looked like a “reign of mobocracy and terror.”

Lincoln had already complained, in January 1837 as a member of the Illinois state legislature, about the “lawless and mobocratic spirit . . . which is already abroad in the land; and is spreading with rapid and fearful impetuosity, to the ultimate overthrow of every institution, or even moral principle, in which persons and property have hitherto found security.” The rising tide of “mobocracy” brought Lincoln, a year later in January 1838, to the Baptist Church in his hometown of Springfield to address the monthly session of the city’s Young Men’s Lyceum. The Lyceum had been casting a worried eye on the upsurge in mobs, taking as its December 1837 topic of discussion, “Do the signs of the present times indicate the downfall of this Government?” Lincoln’s speech a month later was his answer to that question.

Americans, he began, had inherited “the fairest portion of the earth” as well as a “government . . . conducing more essentially to the ends of civil and religious liberty, than any of which the history of former times tells us.” Creating that government had been an immense task, but, having accomplished it, it remained now for the newest generation to preserve and hand on—“undecayed by the lapse of time and untorn by usurpation”—the “political edifice of liberty and equal rights.” Simple enough. But the evidence of the preceding year was that a successful handing-on was by no means certain. And the force that would dash that handing-on to the ground came not from war or invasion but from Americans themselves and a “growing disposition to substitute the wild and furious passions, in lieu of the sober judgment of Courts; and the worse than savage mobs, for the executive ministers of justice.” Was democracy inevitably the victim of the passions?

Lincoln’s suspicion of passion had deep roots, stretching back to the eighteenth-century Enlightenment, for law was simply the public embodiment of the Enlightenment’s reverence for reason. After all, Lincoln was born in 1809, at the end of what is sometimes called the “long eighteenth century,” and his intellectual growth was steeped in the classics of the Enlightenment: Thomas Paine, Constantin Volney, Adam Smith. Central to the Enlightenment was its preference for reason over authority and hierarchy—which is to say, the justification of our beliefs and actions by material or logical evidence, not by testimony or personal emotion. The Enlightenment did not discover reason (as though no one had ever been reasonable before the Enlightenment’s progenitors appeared at the turn of the seventeenth century); the religion of the Old Testament urged, “Come now, and let us reason together,” and the theologians of the Middle Ages devised scholastic inquiries that were monuments to rational inquiry. But the premises on which they erected those rational structures were inherited from authority, and especially the authority of the Bible or Aristotle, or both in tandem. What distinguished the Enlightenment’s reason was the breaking up of the authority of those premises, and the employment of reason as an authority itself, to persuade rather than to threaten.

The first of the ancient premises to crack under the inspection of reason were scientific ones—that the physical universe was a hierarchy, from the earth at the base, through the realms of the planets and stars, to the high heavens—and Galileo and Newton began the cracking. It was only a matter of time before reason deconstructed the political hierarchies of Europe as well. “We live in a century in which the philosophical spirit has rid us of a great number of prejudices,” claimed Denis Diderot in his Encyclopédie in 1749—a century that his countryman Anne-Robert-Jacques Turgot described as “the century of reason.” And under the reign of reason, politics was no more exempt from scrutiny than physics. Once Americans decided that “no truly natural or religious reason can be assigned” to the rule of dim-brained or tyrannical monarchs, then (as Tom Paine declared) “distinction of men into kings and subjects” vanished.

But the reign of reason was itself threatened, partly by the bad example of what happened in the 1790s in Jacobin France, where another revolt against hierarchy turned into an incestuous bloodbath, and partly because of suspicions on the part of many European thinkers (like de Maistre) that reason could not penetrate every secret—or worse, that if it did, it would render them pale, bloodless, and boring. Reason had no greater admirer than Immanuel Kant; yet even Kant warned that reason made mistakes that experience did little to correct. The reasoning mind could deal only with the appearances of things, not the things in themselves, which required an entirely different way of knowing, apart from reason. Enter the Romantics, looking to find the real springs of human identity in the nonrational—in personal experience or identity, in the bonds of tradition, in the sublime, in the occult power of class, nations, soil, race, religion—in passion.

The Enlightenment eyed passion warily, uncertain whether to banish or co-opt it. Anthony Ashley Cooper worried that passion, necessary as it might be to human instinct, could inspire demonic furies, “especially where religion has had to do.” Passion can put people “beyond themselves . . . and in this state . . . the fury flies from face to face, and the disease is no sooner seen than caught.” Especially in politics, “the prudent, the equitable, the active, resolute and sober character” will (according to Adam Smith) generate “prosperity and satisfaction,” but “the rash, the insolent . . . and voluptuous . . . forbodes ruin to the individual, and misfortune to all who have anything to do with him.” A century and a half later, those fears were confirmed all too well, as the “political passions” of the Romantics—“the thirst for immediate results, the exclusive preoccupation with the desired end, the scorn for argument, the excess, the hatred, the fixed ideas”—came within an ace of destroying civilization itself.

It’s unlikely that Lincoln ever laid eyes on Kant, but his school textbook, The Columbian Orator, taught him that, “guided by reason,” nations have “established society and government” that can even “remedy the imperfections, of nature herself.” Reason, for Lincoln, was the guidance of human affairs by “observation, reflection and experiment,” and there was no better example of that guidance than the American Revolution. “Fatally enamoured of their selfish systems of policy,” the British “were deaf to the suggestions of reason and the demands of justice,” and it cost them an empire. So it could only be a “Happy day,” Lincoln would exclaim, “when, all appetites controled [sic], all passions subdued, all matters subjected, mind, all conquering mind, shall live and move the monarch of the world. Glorious consummation! Hail fall of Fury! Reign of Reason, all hail!”

No wonder, then, that in the ears of the Springfield Lyceum, Lincoln identified the mobs of the previous year as an unlovely manifestation of passions that had usurped reason and thrown aside truth and as a sign of political doom for democracy. The American republic, precisely because it was founded on “the capability of man to govern himself,” was most in danger from Americans who had surrendered that “capacity” to passion through “the increasing disregard for law which pervades the country.” In Lincoln’s concept of democracy, reason stood on one side, passion and “outrages committed by mobs” on the other.

He had no difficulty summoning examples: lynching gamblers in Vicksburg; the so-called Madison County slave insurrection of 1835, which led to such reckless retaliation that “dead men were seen literally dangling from the boughs of trees upon every road side”; in St. Louis, a “mulatto man, by the name of [Francis] McIntosh” who was “chained to a tree, and actually burned to death” in 1836; and the “hundreds and thousands” who “ravage and rob provision-stores, throw printing presses into rivers, shoot editors, and hang and burn obnoxious persons at pleasure, and with impunity.” (The editor he had particularly in mind was Elijah Lovejoy of the Alton Observer, who was shot to death by a mob that had attacked his abolitionist newspaper two months before Lincoln spoke to the Lyceum.) A government that rests itself on the people and that does not require a monarch or a class of nobles or an oppressive imperial army to establish order will rapidly lose its self-respect if the people conduct themselves in this way. “Good men, men who love tranquility, who desire to abide by the laws, and enjoy their benefits” but who now see “their property destroyed; their families insulted, and their lives endangered” will become “disgusted with, a Government that offers them no protection,” and will soon enough welcome a monarch or a dictator—anyone who will bring order out of chaos. This, after all, had been the pattern followed by one republican experiment after another—in France with Napoleon, in the South American republics with Bolívar and San Martín, in Mexico with Agustín de Iturbide and Santa Anna.

But worse, if self-government collapsed in the United States, it would drag down with it all hope for liberal democracy everywhere. Despite democratic America’s excesses over the years, nowhere had a democratic republic been more prosperous, and nowhere had successive changes of administrations been more peaceful. If, despite that, democracy yielded to the destructive uproar of passion—if Americans had forgotten the principles of the Revolution that quickly—then “it will be left without friends, or with too few, and those few too weak, to make their friendship effectual” and spell the end of “that fair fabric, which for the last half century, has been the fondest hope, of the lovers of freedom, throughout the world.” Self-government—a principle that Lincoln later cast in terms of “government of the people, by the people, for the people”—can’t survive by passion. It lives only by reason, and the instrument of reason in political life was law.

So the solution to the problem of passion was, for Lincoln, “simple”: treat laws as absolutes, almost as mathematical axioms. “Let every American, every lover of liberty, every well wisher to his posterity, swear . . . never to violate in the least particular, the laws of the country; and never to tolerate their violation by others.” That oath would serve as a surrogate for passion, a “political religion of the nation,” in which “all sexes and tongues, and colors and conditions” should “sacrifice unceasingly upon its altars.” Even when laws proved unwise, let them “be religiously observed” until a proper process of repeal could be effected. Lincoln had no sense of how a civil disobedience to laws could work; it was either strict adherence or “mob law.”

Obedience to the laws would become the American democracy’s fountain of youth, constantly replenishing its stability and prosperity. That did not mean that law was the solution to every situation. In the broadest sense, “the theory of our government is Universal Freedom” for the exercise of the “equal rights of men,” which would thereby “secure the blessings of freedom.” Lincoln had no notion that democratic government was responsible for securing a vague “common good.” Laws should be effective, fair, reverenced—and few. “Government is not charged with the duty of redressing, or preventing, all the wrongs in the world,” he wrote in 1859 in notes for speeches he would give in Ohio. The power of law to promote a “general welfare” was preventive rather than regulative—to “redress and prevent, all wrongs, which are wrongs to the nation itself” and thus “avoid planting and cultivating too many thorns in the bosom of society.” Its scope should be modest: “The legitimate object of government, is to do for a community of people, whatever they need to have done, but can not do, at all, or can not, so well do, for themselves in their separate, and individual capacities.”

For that reason, we could sort the laws that Lincoln hoped Americans would religiously obey into two simple and general categories: “those which have relation to wrongs, and those which have not.” The first category largely involved criminal law—“all crimes, misdemeanors, and nonperformance of contracts.” The other was related to civil law: “All which, in its nature, and without wrong, requires combined action, as public roads and highways, public schools, charities, pauperism, orphanage, estates of the deceased, and the machinery of government itself.” Lincoln was no libertarian. There had to be some common rules for “[m]aking and maintaining roads, bridges, and the like; providing for the helpless young and afflicted; common schools; and disposing of deceased men’s property.” His earliest election speeches for the Illinois legislature teem with pledges to promote road and bridge construction, the creation of a state bank (on the model of the Second Bank of the United States, so hated by Andrew Jackson), “setting a limit to the rates of usury,” lobbying Congress for the sale of public land in Illinois, and even claims for “an estray horse, mare or colt.” And he mocked those who greeted any proposal “to remove a snag, a rock, or a sandbar from a lake or river” with the incessant cry of “no.” Yet the abiding rule for him remained: “In all that the people can individually do as well for themselves, government ought not to interfere.”

But law could not banish passion from American life by its own strength, and nothing underscored that challenge more than the attempt in 1861 of 11 Southern slaveholding states to secede from the Union and form their own slave Confederacy. For nothing seemed to mark secession more than passion. “Madness rules the hour,” Nathan Appleton, the pioneer merchant of American industry, wrote to a Charlestonian, and “loyal men . . . live under a reign of terror which dismays, silences and paralyzes them.” Across the South, denunciation, shaming, shunning, and silencing became the preferred responses. Secession-minded politicians drove wildly toward disunion, “as if they were afraid that the blood of the people will cool down.” Across the South, “a system of espionage prevails which would disgrace the despotism and darkness of the middle ages,” complained Michigan congressman Henry Waldron. “The personal safety of the traveler depends, not on his deeds, but upon his opinions.” Frederick Law Olmsted found that, “in Richmond, and Charleston, and New Orleans,” free society seemed to have disappeared into the grasp of a system of “citadels, sentries, passports, grape-shotted cannon, and daily public whippings,” while the South Carolina legislature was preparing “bills in relation to free negroes, itinerant salesmen, and traveling agents”—as though the murders of Lovejoy and McIntosh were examples of proper response. The Confederacy had become, on a national scale, the mobs he deplored a quarter-century earlier in the Lyceum speech.

In 1861, as much as in 1838, Lincoln identified passion as the culprit at the root of this ideological bullying, and he even scolded his own party in 1860 for trying to fight Southern passion with Northern passion. “Let us do nothing through passion and ill temper,” he said, and he told the New York state legislature that we must “restrain ourselves” and “allow ourselves not to run off in a passion.” But Southern passion was the element he feared most. “We must not be enemies,” he pleaded in his Inaugural Address. “Though passion may have strained, it must not break our bonds of affection.” Southerners would find that they “can have no conflict without being yourselves the aggressors.” Passion, whether in the form of Jacksonian mobs or paranoid slaveowners, might threaten to send democracy off its legal rails, but he, for one, would resist it by every means at hand. The stakes were too high not to. “This country, Sir, maintains, and means to maintain, the rights of human nature and the capacity of man for self-government,” he told a newly arrived European envoy in November 1861. And he reminded Congress that the war “presents to the whole family of man, the question, whether a constitutional republic, or a democracy—a government of the people, by the same people” can be broken up and “organic law” shouldered aside. The result, as he had warned the Lyceum, was that this would “practically put an end to free government upon the earth.” He did not “deny the possibility that the people may err in an election,” he said after his own election as president, but the solution is not an illegal riot. If the people “err,” then “the true cure is in the next election.”

Lincoln promised to employ “all indispensable means” in suppressing the Confederate rebellion. But as much as he would reach for whatever tools he thought might save democracy, they would still be the reasonable tools of law. No “spirit of revenge should actuate his measures,” he told a Maryland legislative delegation, and, writing to a Louisiana Unionist in 1862, he promised that “I shall do all I can to save the government.” But “I shall do nothing in malice. What I deal with is too vast for malicious dealing.” He made no claim to possessing all wisdom; quite the contrary, he told one of his generals, irked at what the general thought was a slight, “I frequently make mistakes myself, in the many things I am compelled to do hastily.” He would instead be guided by “the dictates of prudence, as well as the obligations of law.” Above all, he would not let himself believe that reason wouldn’t eventually prevail, even among the Southern public. “At the beginning,” the fire-eaters and warmongers in the Confederacy “knew they could never raise their treason to any respectable magnitude, by any name which implies violation of law.” But Southerners, as much as any other American, were “possessed as much of moral sense, as much of devotion to law and order, and as much pride in, and reverence for, the history, and government, of their common country, as any other civilized, and patriotic people.”

Lincoln had appealed to that devotion in 1838. It would be pleasant to say that his words had proved the charm then, but we have no evidence that anyone was paying much attention to a garrulous lawyer from Springfield, Illinois. In 1861, with Lincoln as president, Americans had no choice but to listen to him. Yet it is not clear that the country heeded his plea for reason and law. Lincoln himself was anxious that too many Northerners at the war’s end were as governed by “hate and vindictiveness” as the secessionists had been at the beginning, and fully as eager to bring down unconstitutional vengeance on Southern heads. Is there, after all, “in all republics, this inherent, and fatal weakness?” he asked. It is a question that, to Lincoln’s dismay, was not precisely answered, except by an assassin’s bullet.

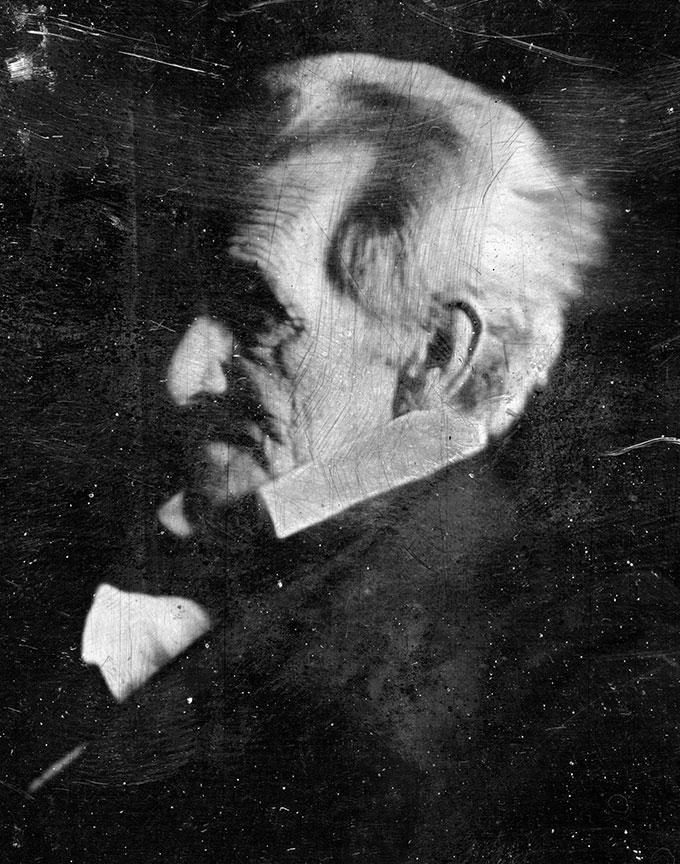

Top Photo: For Lincoln, Americans had “the best Government the world ever knew”—a government in which “the people” had the “right to decide the question,” whatever the question might be. (Photo by: Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty Images)