Liu Xia, widely recognized and admired by the artistic and intellectual community in Beijing, may be the most important photographer in China today. She is also, however, a forbidden artist. Six of her photographs, shown below, never received the Chinese government’s permission to leave China; they had to be smuggled out. Liu Xia herself disappeared this past January, placed under house arrest somewhere in Beijing by police without so much as an indictment, much less a trial. Nobody knows where she is.

Why such censorship for rather abstract photos? Why do they make the Chinese government so angry? Not because Liu Xia is a political activist; like most artists, she longs for freedom, but she isn’t an active dissident. No, the repression has only one explanation: Liu Xia is the wife of Liu Xiaobo, the 2010 Nobel Peace Prize recipient, jailed for 11 years for threatening the security of the state. His only crime was to have written a petition—an act permitted by the Chinese constitution, by the way—asking for dialogue with the Communist Party in order to organize a transition toward democracy. This petition, circulated on the Web, was signed by several thousand Chinese scholars and artists.

When Liu Xia is asked why she has shaved her hair, she answers that she will let it grow again when China is free. She wonders, too, why the West doesn’t support Chinese democrats as it once supported Russian dissidents. “Aren’t we human?” she asks. “Or are you waiting until all democrats in China are exterminated—and then you will cry for us?”

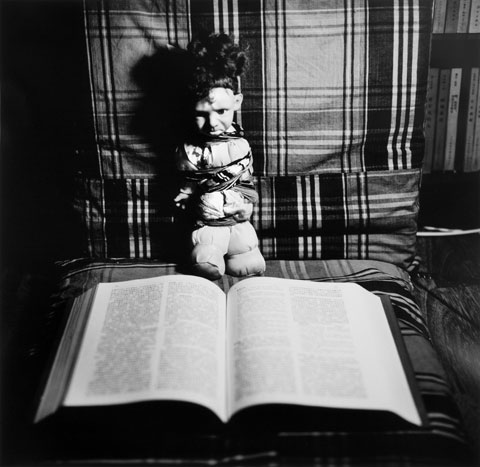

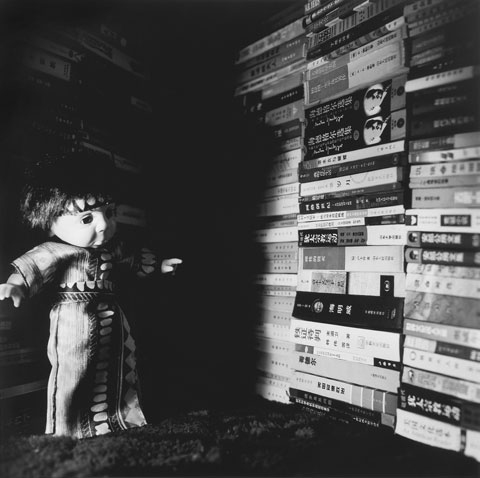

Today, an exhibit of Liu Xia’s photographs opens in the Boulogne Museum, near Paris. This is the first time that the photos are being shown in public; until now, they could be seen only in private, either at Liu Xia’s apartment or circulated among enlightened amateurs in Beijing. The exhibit, The Silent Strength of Liu Xia, highlights the artist’s use of black and white—an homage to the ancient art of calligraphy, the source of all the arts in China. In Liu Xia’s work, we see the strange puppets that she calls her “ugly babies” wandering like ghosts in Beijing. The idea, sadly irrelevant in the end, was that the censors wouldn’t be as alarmed at photos of dolls as at photos of real people. In the final photograph, though, we do see Liu Xiaobo.

Liu Xia is not the only major Chinese artist punished for failing to serve the Party. Gao Xingjian, a Nobel laureate for literature, has been exiled and lives in France. Ai Weiwei, whose sculptures have been shown in New York, was jailed this year for two months without explanation; today, in Beijing, he isn’t allowed to talk to foreigners. One might expect the Communist Party to celebrate the Chinese cultural renaissance being created by the country’s world-recognized artists. Since it doesn’t, the obvious conclusion is that the Party fears the creativity of its own subjects—a common feature of all doomed oppressive regimes.