The Publisher: Henry Luce and His American Century by Alan Brinkley (Knopf, 560 pages, $35.00)

To the list of endangered species, headed by the Giant Panda and the White Rhinoceros, another genus should be added: the American Press Lord. One by one, journalism’s great leaders—Joseph Pulitzer, William Randolph Hearst, Adolph Ochs, Col. Robert R. McCormick, Otis Chandler, Katherine Graham, and Henry Luce—have been swallowed up by history.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

Even so, a romantic aura surrounds them, decades after their deaths. Some of it can be attributed to the long line of movies about newsgathering, ranging from Citizen Kane and The Front Page to All the President’s Men and The Insider. But mostly it comes from the realization that blogs and cable news networks are replacing print media or rendering it irrelevant. Whatever the press lords’ flaws (and they had many), their properties showcased the work of memorable writers, editors, and photographers. Quite a contrast to most periodicals now on sale at the supermarket.

Perhaps the most influential of those bygone publishers has become the most obscure. Yet in his day—1923, the date of the first issue of Time, to 1967, the year of his death—Henry Luce was a famous festival of contradictions, at once admired for his vision and excoriated for his views. He stood foursquare for American exceptionalism, for example, yet opened news bureaus in Europe, Asia, and Africa. He hated Franklin D. Roosevelt and ceaselessly boosted Republican candidates, yet knowingly hired card-carrying Communists. His Time praised the Italian fascist Benito Mussolini as a “person of high moral integrity” who deserved “unstinted praise and congratulations.” Yet when many American publications fell for Joseph Stalin, Luce’s magazines had his number down to the tenth decimal point, referring to the Generalissimo as “Dictator Stalin,” and characterizing him as a “coldblooded man of deeds” with a “mask of oriental ruthlessness.”

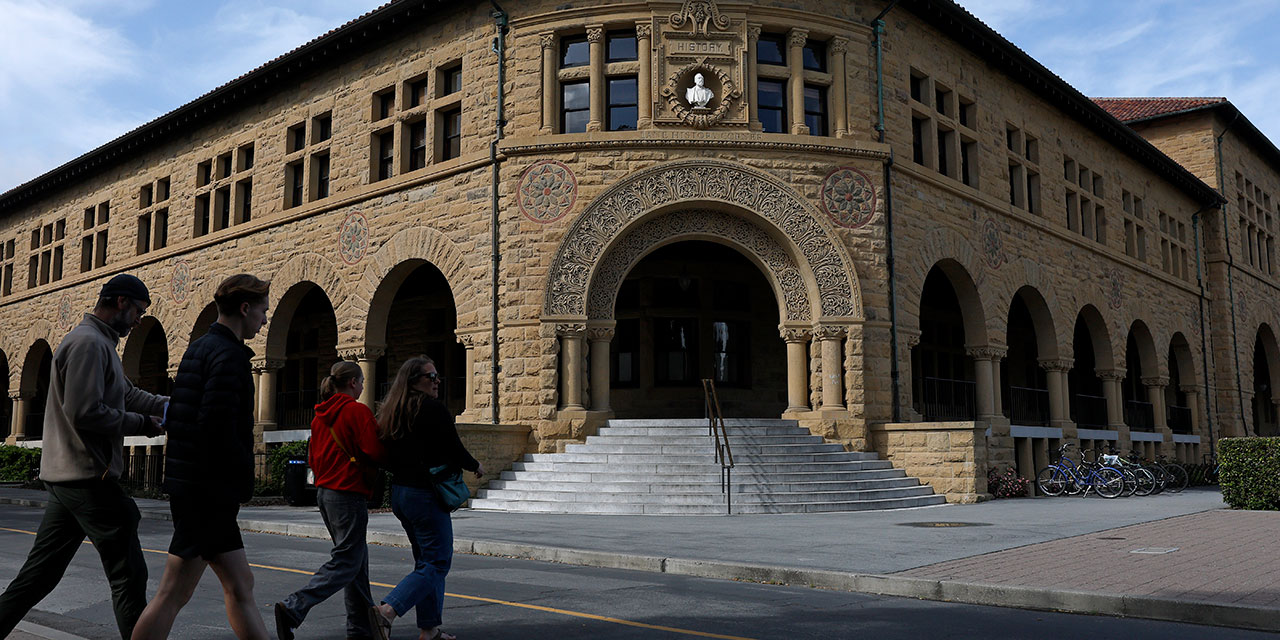

Alan Brinkley, the Allan Nevins Professor of American History at Columbia University, is the author of several previous books, most notably Voices of Protest: Huey Long, Father Coughlin, and the Great Depression. He knows how to place an individual in context, and his latest work, The Publisher, shrewdly examines the sources of Luce’s ambiguities and his extraordinary rise to prominence.

The super-American was born in imperial China, the son of a Presbyterian missionary. The reverend Henry Winters Luce was determined to have his “brilliant” son return to the States when he came of age. And so, at 14 Henry Robinson (“Harry”) Luce entered Hotchkiss prep school and then went on to his father’s alma mater, Yale. There Harry was tapped for the exclusive undergraduate society, Skull and Bones. One day he and a fellow member, Britton Hadden, discovered that they shared the same ambition. After graduation, the two young men scraped up enough cash to realize their dream: a magazine with “a comprehensive view of the week’s news that could be read in less than an hour.”

Their timing was metronomic. America’s burgeoning middle class felt the need to keep up with, and interpret, current events. Two 24-year-olds, Hadden and Luce, furnished them with the means. Time took a taxonomic approach to the news, breaking it down into departments like Nation, Science, Religion, and Sport, and enlivening the prose with Homeric “wine-dark sea” constructions. No one had seen anything like it, and subscribers soon numbered in the millions. So did the bank accounts of the partners. They were rich and celebrated before their 30th birthdays.

Hadden never reached his 32nd. He died of a streptococcus infection in 1929, leaving Luce to run the nascent Time Inc. empire by himself. He retained much of Haddon’s quirky prose style—as a celebrated New Yorker parody put it, “backward ran the sentences until reeled the mind,” and “where it will all end, knows God.” But Luce was impervious to criticism. As Brinkley notes, the surviving partner went from strength to strength. In 1930 he founded Fortune magazine, the most elegant business-oriented publication of its epoch. Luce commissioned prominent artists to design the covers, among them Rockwell Kent, Diego Rivera, Charles Sheeler, and Ferdinand Leger. Fortune gave Margaret Bourke-White her first major assignments, thrusting her into the all-male world of photojournalism. Aware that businessmen could not write poetry, but that poets could write about business, Luce hired Archibald MacLeish and James Agee.

A great many of the personalities who surrounded Luce leaned left (Ralph Ingersoll, the editor of Time, departed to found the radical newspaper P.M.) Often they collided with their boss, but that was just fine with Luce. He didn’t mind the heat as long as it was accompanied by light. In later years the corporation produced Life, a magazine, Brinkley observes, that aimed to be “the celebratory face” of the “new suburban civilization.” Life also leapt off the newsstands, followed by the popular March of Time documentaries that covered the American experience, with particular attention paid to World War II. And, in 1954, at Luce’s insistence, the company published Sports Illustrated over the objections of some top executives. (One of them, conscious of baseball’s status as the nation’s number one sport, pleaded, “Harry, what are they going to read in the winter?”) SI also became a phenomenal profit-maker, taking advantage of the new TV coverage of basketball, football, and golf.

In those days, Harry could do little wrong—except in his marriage. To Brinkley’s credit, he keeps gossip to a minimum. Luce’s second wife, playwright Clare Booth, was an unhappy woman, and as the years passed their union became less of a romance and more of a business arrangement. “The paintings he gave to me for my birthdays and Christmases,” lamented Clare, “were not really gifts to me,” but the property of Harry’s estate.

Brinkey’s main focus is on the man in his Time. En route, The Publisher offers a refreshing change from the previous Luce biography, W.A. Swanberg’s Luce and His Empire, a compendium of 1960s bromides, portraying the mogul as a war-mongering despot whose periodicals conspired to drown human rights in a sea of capitalism. Naturally, it won a Pulitzer Prize in 1973. Brinkley is too much of a gentleman to take on his predecessor point by point, but he refutes him by pointing out that Luce actually “embraced many of the great changes” of the 20th Century—the “growth of the welfare state, civil rights for minorities, and, at least tentatively, the emergence of feminism and gender equality.” Moreover, he “understood the broad transformation of the capitalist economy in the postwar years, supported unions to ensure that the profits were not reserved to a few, and applauded what he considered ‘modern’ industrial leaders who believed in progressive corporate responsibility.”

No doubt Luce was a complicated man, hard to know, and even more difficult to work for. But those who would denigrate his achievement have only to read Brinkley’s fair-minded assessment to see how wrong they are. If they’re too lazy to do that, they can examine the pages of America’s shrinking newspapers and newsmagazines, with their predictable bumper-sticker editorials, recycled columnists, and harrumphing op-ed pieces. Giants really did roam the earth in days gone by. Their triumph is the work they produced and inspired. Their tragedy is the failure to throw long shadows.