Before there was Pop Art there was popular art, and the most popular art was the comic strip, and the most popular of the comic-strip artists was Al Capp. Last year marked his centenary, a time when his accomplishments should have been celebrated nationwide with exuberant features and illustrations. Instead, Capp’s name was neglected by everyone except pop historians and those with indelible memories of Dogpatch, U.S.A. The reasons have less to do with fashions in newspaper comics than with trends in newspaper politics. In the mainstream media, the man in cap and bells wins ovations so long as he toes the line, mocking red-staters and GOP conservatives. But woe to the jester who kids the Left.

The eldest child of Latvian-Jewish immigrants, Alfred Gerald Caplin was born in 1909 in New Haven, Connecticut. He enjoyed a typical New England boyhood until the age of nine. In autumn 1918, he sneaked aboard an ice truck, jumped off—and fell into the path of an oncoming trolley car. His left leg was severed in mid-thigh. “There came a great noise—a great cry—a crash—and darkness,” he recalled. “And the gate of the garden closed.” When Alfred’s wound healed, he received the first of many prostheses. “I was indignant as hell about that leg,” he continued. “It was hard to handle, and it squeaked.” At the same time, though, he learned “the secret of how to live without resentment or embarrassment in a world in which I was different from everyone else.” It was to be “indifferent to that difference.”

Otto Caplin wasn’t much of a provider, but he gave his son something more valuable: encouragement. Otto was a compulsive doodler, and he saw that his boy had a gift for drawing. He praised Alfred’s efforts and urged him to do more of them. Soon, working with a pencil and sketch pad was one of only two things that interested the dark-haired, handsome youth. The other was girls. After failing geometry for nine consecutive terms, Alfred dropped out of high school and began to explore the world beyond New Haven. The limping hitchhiker roamed as far south as Appalachia, where illiterate but hospitable farmers allowed him a free overnight berth—and where he made the acquaintance of their comely daughters. Alfred began wondering how he could combine these interests; when he returned home, he thought there might be a way. He had read enticing stories about Bud Fisher, the creator of Mutt and Jeff, who “got $3,000 a week and was constantly marrying French countesses. I decided that was for me.”

When Alfred was 19, the Caplin family moved to Boston, where Otto hoped (vainly) to earn big money as a salesman. Alfred picked up a few pointers at Boston’s School of the Museum of Fine Arts, but the talent, humor, and ambition were already in place. What they needed was an outlet. In 1933, the young artist packed up his portfolio, journeyed to New York, and wangled an interview with one of America’s top cartoonists. Ham Fisher was the creator of Joe Palooka, whose comic-strip exploits had made the big time, with radio shows and films built around the amiable prizefighter. Busy with innumerable projects, Fisher hired Caplin as an assistant.

Theirs was not a happy or long-lived association. Alfred furnished Joe Palooka with ideas, drawings, and characters (among them a few Appalachian walk-ons); Ham supplied minimum wages. As Time later noted, “Capp parted from Fisher with a definite impression (to put it mildly) that he had been underpaid and unappreciated. Fisher, a man of Roman self-esteem, considered Capp an ingrate and a whippersnapper.”

On his own time, the whippersnapper came up with Li’l Abner and with a nom de strip, Al Capp. The central character was a strapping, empty-headed mountain boy, Abner Yokum—a portmanteau moniker that blended “yokel” and “hokum.” In Abner’s hick town of Dogpatch, the farms produced only turnips. The comedy was Manichean: the local women were either gorgeous or gorgons, the men either virtuous or villainous. They all spoke in a unique Southern vernacular: “amoozin’ but confoozin’ ”; “if I had my druthers”; “corn-tinue.” And their dialogue was punctuated with G-rated expletives like “Gulp!” and “Sigh!”

United Features Syndicate took a chance on the strip, and Li’l Abner debuted on August 13, 1934, at the nadir of the Depression. No one had seen anything like it. Capp combined narrative skill, native wit, and an ability to draw pneumatic women. (“Anyone who likes small bosoms,” he proclaimed, “let ’em read Orphan Annie.”) That year, Abner became the sleeper of the comic pages. By 1937, it was running in 250 newspapers; by the 1950s, about 1,000 papers brought it to more than 60 million readers.

Dogpatch became as familiar as William Faulkner’s Yoknapatawpha County, and a lot more entertaining. There was, for example, Sadie Hawkins Day, the one time in the year when women were encouraged to run after men. The pursuit takes place at a racetrack, with an official, “Marryin’ Sam,” waiting at the finish line. Upon arrival, the ladies and the bachelors they have snagged are joined in unholy matrimony. The idea caught on. In 1939, a double-page spread in Life reported: “On Sadie Hawkins Day, Girls Chase Boys in 201 Colleges.” A dozen years later, the day was celebrated, on and off campus, in some 40,000 venues.

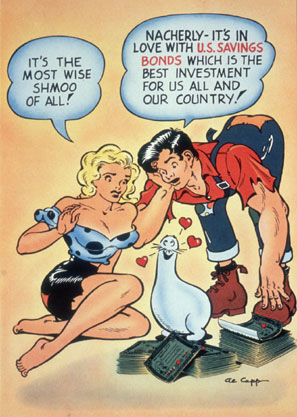

In the summer of 1948, Li’l Abner ventured into the Valley of the Shmoos. These armless, harmless, pear-shaped creatures lived—and died—to please humanity. Shmoos happily immolated themselves for the hungry, leaping into a frying pan (after half an hour on the heat, they tasted like chicken) or into a broiling pan (in which case they tasted like steak). Shmoos produced eggs, milk, and butter; their pelts made perfect boot leather or house timber, depending on how thick they were sliced. Unfortunately, the generous animals wreaked havoc on business: who would pay for food or shelter when Shmoos were around? So they were annihilated by “Shmooicide Squads” funded by J. Roaringham Fatback, the gluttonous Pork King. The satire caught on nationally, accompanied by attacks from both the Left and the Right, notes comic-book publisher Denis Kitchen. “Communists thought Capp was making fun of socialism and Marxism. The right wing thought he was making fun of Capitalism and the American way.” For Al, every knock was a boost. “If the Shmoo fits,” he proclaimed, “wear it.”

Molasses-brained Abner was semiliterate, but he could read the dialogue balloons in Fearless Fosdick, a hilarious send-up of Chester Gould’s plainclothes sleuth, Dick Tracy. The strip-within-a-strip set Fosdick, Abner’s “ideel” man, against a series of antagonists, including Rattop, Bombface, and Sidney the Crooked Parrot. In every adventure, malefactors filled the hero with huge bullet holes. But Fearless, looking like a piece of animated Swiss cheese, perennially responded, “Fortunately, these are mere flesh wounds,” and saw to it that good triumphed over evil. The parody lasted 35 years; many weeks, Fosdick received more fan mail than Tracy himself.

Li’l Abner costarred a procession of colorful folk whose names described their characters or their physiognomies. Among the ladies: Appassionatta Von Climax, Stupefyin’ Jones, and Moonbeam McSwine. The men included Romeo McHaystack, B. Fowler McNest, Battling McNoodnik, Slobberlips McJab, Bounder J. Roundheels, Oldman Riva, Sir Orble Gasse-Payne, and Skelton McCloset.

Li’l Abner leaped from the newspapers and took off in all directions. In 1940, RKO produced a film based on the strip; it featured some former Keystone Kops, as well as Buster Keaton as a character named Lonesome Polecat. Four years later, Li’l Abner inspired a series of animated cartoons for Columbia Pictures. Three years after that, Capp was wealthy enough to buy back his contract from United Features, thereby enabling him to profit from every aspect of the strip, from theatrical adaptations to product endorsements. The lifelong teetotaler pitched Schaefer beer as well as Wildroot Cream Oil; Abner’s parents, Mammy and Pappy Yokum, pushed Cream of Wheat and Grape-Nuts along with Ivory soap and Fruit of the Loom underwear. In the next decade, Dogpatch became the backdrop of a Broadway musical with Peter Palmer as Abner, Edie Adams as his perpetual girlfriend Daisy Mae, and pulchritudinous showstoppers Tina Louise and Julie Newmar as, respectively, Ms. Von Climax and the truly Stupefyin’ Jones.

Under reader pressure, Capp allowed Abner and Daisy Mae to marry in 1952, an event reported worldwide—indeed, the wedding made the cover of Life. Capp himself was on the cover of Newsweek and became the subject of a two-issue profile in The New Yorker. This burgeoning celebrity was a delight to Al, his wife, Catherine (whom he had met in art school), their three young children, and millions of fans.

But it was not pleasing to Ham Fisher. As the years wore on, Abner Yokum completely eclipsed Joe Palooka. Fisher bad-mouthed Capp at meetings of the National Cartoonists Society, insisting that the younger man’s bumpkins derived from work he had done on Joe Palooka. Capp returned fire, caricaturing Fisher in Li’l Abner as avaricious cartoonist Happy Vermin. For lagniappe, he published an essay in The Atlantic Monthly. Though “I Remember Monster” never referred to Capp’s ex-employer by name, it described a cruel, parsimonious boss widely understood to represent Fisher. Ham retaliated, accusing Al of sneaking pornography into the backgrounds of his comic strip. Exhibit A was a sheaf of X-rated drawings, showing steamy bimbos in compromising positions. Fisher submitted them to Capp’s syndicate and to a New York judge. The aim was to embarrass Capp publicly—and to get him thrown out of the Society. Capp countered with irrefutable evidence. He showed the court and the Society his original, unsullied drawings, suggesting that “someone else” had drawn the blue material. The judge let the matter drop; so did the Society.

But the vendetta was far from over. In 1954, when Capp made an offer to buy a Boston television station, the Federal Communications Commission received an envelope with no return address. It contained more pornographic Li’l Abner drawings. At Capp’s urging, the Society held an investigation. Fisher was accused of forgery and expelled. The following year, he committed suicide in his studio. By then he had become a lonely outcast, living in obscurity and disgrace. His body was not found for almost three months.

Capp said nothing when he heard the news, but he made certain that he would never be accused of shortchanging or maligning his own assistants. When Time put him on its cover, the working routine of Li’l Abner became a matter of record. It began, Al demonstrated, with his own pencil sketches and dialogue. Andy Amato and Walter Johnson added backgrounds and objects to the drafts. Harvey Curtis did the lettering. The fifth member of the team, Frank Frazetta, added fine touches to characters and scenes. (He later became well-known for his painted book covers and movie posters and for the sex satire Little Annie Fanny in Playboy.)

Still, the main credit belonged to the man whose signature decorated the bottom of the comic strip. After all, Al Capp was the one who produced the ideas and the characters that kept America laughing. The satirist’s energy seemed limitless. “Is there hypocrisy and injustice waiting for me to take ’em on?” he remarked. “Glad to oblige.” As if he didn’t have enough on his drawing board, Capp cocreated two more newspaper strips, Abbie an’ Slats with Raeburn Van Buren and Long Sam with Bob Lubbers. He also worked on the shorter top-of-the-page cartoons Washable Jones, Small Fry, and Advice fo’ Chillun.

But it was Li’l Abner that prompted the National Cartoonists Society to present him with a Reuben, its highest award. And it was Li’l Abner that garnered a long list of celebrated admirers, among them Charlie Chaplin, Harpo Marx, theatrical caricaturist Al Hirschfeld, economist John Kenneth Galbraith, and Queen Elizabeth II. John Updike called Abner a “hillbilly Candide”: the strip’s “richness of social and philosophical commentary approached the Voltairean.” That jibed with John Steinbeck’s assessment that Capp was “the best satirist since Laurence Sterne,” worthy of a Nobel Prize in Literature.

Al was interviewed by Jack Paar and Steve Allen on The Tonight Show and was the guest of avid intellectuals in Italy. “What was your motivation for creating Li’l Abner in 1934?” one of them asked. Capp: “Hunger. I was very hungry in 1934. So I created Li’l Abner. It became big business and I became overweight. Since then my motivation has been greed.” He appeared at colleges nationwide, exhorting students to think for themselves, and at gatherings of disabled veterans, encouraging them to be indifferent to the difference. Though Capp voted for Democrat Adlai Stevenson in 1952 and 1956, President Eisenhower asked him to chair the Cartoonists Committee of the Treasury Department’s People-to-People program, encouraging the purchase of U.S. Savings Bonds. Al also was a member of the National Reading Council, a group dedicated to promoting literacy.

During the sixties, Capp lived in Cambridge, Massachusetts. For him, news of student protests against the Vietnam War, against President Nixon, against college administrators, against the police, and finally against anyone who dared to espouse traditional values weren’t remote events reported in the same papers that carried Li’l Abner. They took place in Al’s own neighborhood: Harvard Yard. He saw what was happening and took notes.

For decades, the New Deal Democrat had been sniping at plutocrats and politicians. Now, provoked by domestic and national circumstances, he turned his artillery on the Left. One group of yapping, in-your-face student radicals called itself the Youth International Party (YIP). The Yippies went for street theater: running a pig for president and flying a flag with a green cannabis leaf superimposed over a red star, for example. Another collection of undergraduate activists, Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), denounced the United States as imperialist and embraced the benefits of drugs, free love, and social revolution in bumper-sticker platitudes.

Capp was having none of it. In Li’l Abner there suddenly marched a repellent group: Students Wildly Indignant about Nearly Everything (SWINE). These unwashed radicals take over the country when a mysterious substance immobilizes anyone who bathes. Capp also introduced a folksinger named Joanie Phoanie, who urges others to violence while she eats caviar in a stretch limo. Many believed this to be a caricature of song stylist and composer Joan Baez, who threatened to sue for libel (but never did).

Never one to duck a confrontation, Capp journeyed north to a Montreal hotel room, where John Lennon and his new wife, Yoko Ono, were staging a “Bed-In for Peace.” After the Lennons received the cartoonist in their pajamas, surrounded by a reverential camera crew, Capp ridiculed the jacket of their latest album, Two Virgins, on which they appeared nude. “I think that everybody owes it to the world to show they have pubic hair,” he said wryly. “You’ve done it, and I tell you that I applaud you for it.” The exchange grew heated. As Capp left the room, Lennon sang a hostile, slightly altered version of his lyric for “The Ballad of John and Yoko”: “Christ, you know it ain’t easy / You know how hard it can be / The way things are going / They’re gonna crucify Capp.”

Hardhat iconoclasm became Al’s preferred mode of expression: “Anyone who can walk to the welfare office can walk to work.” “Abstract art is a product of the untalented, sold by the unprincipled to the utterly bewildered.” “I have never actually seen a French New Wave movie, because of my conviction that they are all Doris Day scripts filmed backward.” Indeed, to emphasize his take on current events, he wrote and illustrated The Hardhat’s Bedtime Story Book, aiming it for the pro-Nixon, salt-of-the-earth, blue-collar workers who had always disdained the Left, Old or New. In his little volume, Capp lampooned those he regarded as the leading Limousine Liberals, including Jane Fonda (who became Jane Porna) and Paul Newman (Paul Newleft).

Though the Capps moved to rural New Hampshire, Al spent a lot of time on the road, facing down college students on campuses across the country. “Today’s younger generation is no worse than my own,” he would begin amiably. Then came the punch line: “We were just as ignorant and repulsive as they are, but nobody listened to us.” The reason journalists and retailers had started to pay attention was purely economic: the students “have $13 billion to spend. Never before has it been so profitable to kiss the ass of the kids. Half of the records they go out and buy today are ‘hate America’ records.”

Capp knew that exaggeration is the royal road to attention, but au fond he was sincere about his political and social beliefs. Back when Al had tilted against the Right, against Senator Joe McCarthy’s irresponsible accusations, and against gluttonous businessmen and establishment politicians, he had been hailed as an exemplar of courage wrapped in comedy. But “when I began to mock the liberals,” he observed, “there came a deluge of hate mail which never ended.”

Capp had altered far less than the groups he now maligned, though. The Democratic Party, to which he had been loyal for decades, had been taken over by its most radical members. During political debates, the upraised fist and accusatory voice had usurped the place of civilized exchanges. On campus, the enemy was no longer defined as someone who threatened democracy, but as anyone who made the mistake of being over 30. Nevertheless, Al explained, the students he blasted were “not the dissenters, but the destroyers—the less than 4 percent who lock up deans in washrooms, who burn manuscripts of unpublished books, who make combination pigpens and playpens of their universities. The remaining 96 percent detest them as heartily as I do.”

No doubt Al Capp was a bitter man by the time he reached his seventh decade. The four-pack-a-day smoker was experiencing severe lung trouble. Li’l Abner was running out of readers. The increasing leg pain made traveling difficult. Capp’s youngest daughter died in her mid-forties, and a beloved granddaughter was killed in a car accident. Yet with all these burdens, his latest assaults were really no more savage than his previous ones. In those strips, the roster of Li’l Abner scoundrels had included the aforementioned robber baron J. Roaringham Fatback, the sclerotic Senator Jack S. Phogbound, and the world’s richest man, General Bullmoose. Readers and critics greeted these reactionaries with the laughter of recognition. Not until Al started lampooning the likes of Ted Kennedy—whom he called O. Noble McGesture—was his strip accused of losing its sense of humor.

Alas, toward the end the cartoonist damaged his own cause. Invited to lecture at the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa, he hit on several coeds. Campus officials forced him to leave. At the University of Wisconsin, a married student accused him of trying to molest her, and a judge fined him $500 for “attempted adultery.” Syndicated columnist Jack Anderson got wind of these incidents, and in 1971 he ran a story portraying Capp as a dirty old man. Newspapers quietly began to drop Li’l Abner. Al got the message and quit in 1977, rather than risk more embarrassment. He explained to readers, “It’s like a fighter retiring. I stayed on longer than I should have. I can’t breathe anymore.” That was an honest self-appraisal. Two years later, he died of emphysema. The newspaper and television obituaries were detailed and affectionate.

In a memorial poem entitled “The Shuttle,” John Updike remembered meeting Capp in a sparsely filled commercial airliner and mentioning a social occasion that they had both attended:

one of those Cambridge parties

where his anti-Ho politics

were wrong, so wrong

the left eventually broke his heartI recalled this to him,

but did not recall how sleepy

he looked to me, how tired

with his peg-legged limpand rich man’s blue suit

and Li’l Abner shock of hair.

He laughed and said to me,

“And if the plane had crashed,can’t you see the headline?—

ONLY EIGHT KILLED

ONLY EIGHT KILLED: everyone

would be so relieved!”Now Al is dead, dead,

and the shuttle is always crowded.

Since that time, Capp has become something of a nonperson, at least in elite press outlets. True, connoisseurs of cartoons know his name—there are some 40 books in print anthologizing or analyzing Capp’s work. And the U.S. Post Office recognized Li’l Abner in 1995 when it chose the strip as an American classic and put it on a 32-cent stamp. But the man himself remains in exile, a sinner who broke from the fold.

A great pity. For Al Capp was, all of his professional life, a soothsayer. Praising the first two-thirds of his work and denigrating the last third is like chortling at the first 60 minutes of a Marx Brothers movie and panning the final 30. Capp had an unerring eye for the poseur in business, in the academy, and in politics—left, right, and center—and his satire was all of a piece. Abner doubters and Al haters should take a long look at The Best of Li’l Abner and The World of Li’l Abner (both can be bought online) and judge for themselves. Capp may have been confoozin’ in real life, but for over 40 years his work stayed amoozin’. No other cartoonist has come close to that achievement; it deserves public recognition. Glad to oblige.