Certain must-pass ideological litmus tests have arisen for the 25 declared candidates (so far) seeking the Democratic Party presidential nomination. Perhaps chief among them is subscription to the belief that the American criminal-justice system is racist and overly punitive. This Democratic unanimity makes sense in light of the criticism that many of the leading candidates have faced from activists, left-wing media, and other, more “woke,” presidential hopefuls for their earlier acceptance, or even endorsement, of proactive policing, quality-of-life enforcement, and incarceration as reasonable methods of combating crime.

JOE BIDEN’S ROLE IN ’90S CRIME LAW COULD HAUNT ANY PRESIDENTIAL BID, ran a prescient 2015 New York Times headline. Doubtless sensing vulnerability, the former vice president and current Democratic front-runner made a Martin Luther King Day speech to Al Sharpton’s National Action Network this year, telling the audience that “I haven’t always been right” about criminal justice and that “white America has to admit there’s still a systematic racism, and it goes almost unnoticed by so many of us.”

That hasn’t stopped some of Biden’s Democratic opponents (not to mention President Trump) from pushing the incarceration button. California senator Kamala Harris, one of his leading rivals, hit Biden for backing the 1994 omnibus crime bill, which, she says, contributed to “mass incarceration in this country.” Harris herself, though, has met criticism for being too tough on crime in her days as a prosecutor and as California attorney general. New Jersey senator Cory Booker—one of the most outspoken of the candidates on criminal-justice reform—has also had his reformist credentials questioned, with a recent Times story criticizing his “zero-tolerance” approach to crime when serving as Newark’s mayor from 2006 to 2013, citing ACLU complaints. But all the Democrats are striking the same chord. “More people [are] locked up for low-level offenses on marijuana than for all violent crimes in this country,” Massachusetts senator Elizabeth Warren, another top-tier Biden challenger, declared at last year’s We the People Summit. Bernie Sanders, the Vermont senator known best for his left-wing economic populism, has described felon disenfranchisement as racist voter suppression. And South Bend mayor Pete Buttigieg told Out that incarceration is “clearly worsening some of the patterns of racial inequality in our country.”

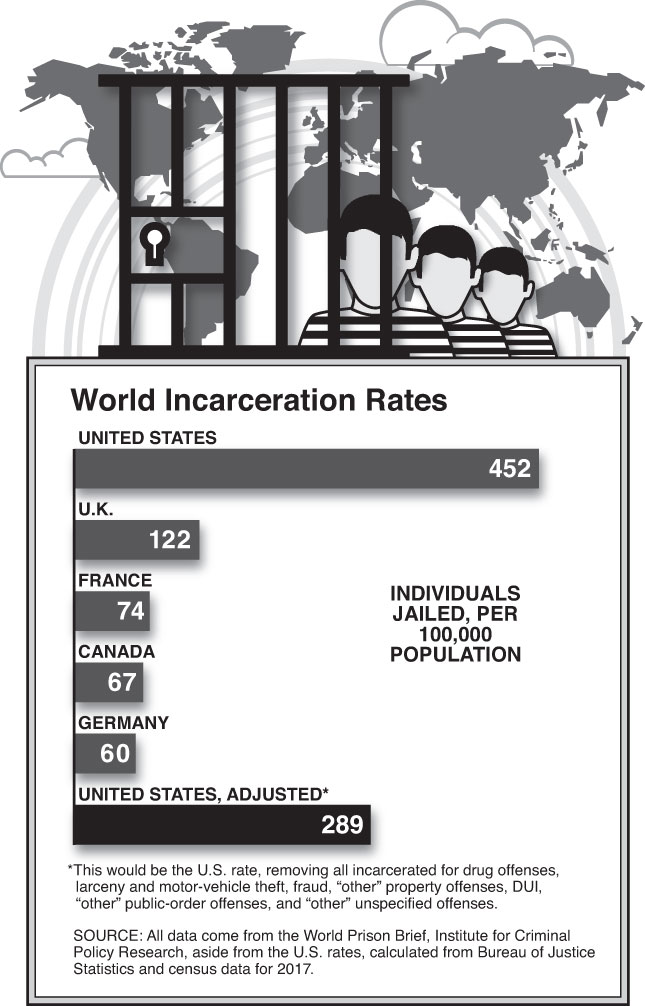

Eight of the declared candidates contributed to a recent compendium published by the Brennan Center for Justice, titled Ending Mass Incarceration. The essays provide a useful summation of Democratic talking points on criminal justice. That the United States over-incarcerates is evidenced, reformers say, by the numbers: though it has about 5 percent of the global population, the U.S. houses about a quarter of the prisoners worldwide. America’s high incarceration rate, goes another assertion, is driven by the unjust enforcement of “low-level” and “nonviolent” offenses, particularly drug crimes. A further charge: the system is racist, given how much more likely blacks are to be behind bars compared with whites. Finally, they say that sentences have gotten way too long.

True, for a subset of America’s prison population, incarceration does not serve a legitimate penological end, either because these individuals have been incarcerated for too long or because they should not have been incarcerated to begin with. Justice dictates that we identify these individuals and secure their releases with haste. But none of the above claims advanced by the presidential hopefuls is correct—and acting on any of them would be disastrous.

Start with drugs. Contrary to the claims in Michelle Alexander’s much-discussed 2010 bestseller The New Jim Crow, drug prohibition is not driving incarceration rates. Yes, about half of federal prisoners are in on drug charges; but federal inmates constitute only 12 percent of all American prisoners—the vast majority are in state facilities. Those incarcerated primarily for drug offenses constitute less than 15 percent of state prisoners. Four times as many state inmates are behind bars for one of five very serious crimes: murder (14.2 percent), rape or sexual assault (12.8 percent), robbery (13.1 percent), aggravated or simple assault (10.5 percent), and burglary (9.4 percent). The terms served for state prisoners incarcerated primarily on drug charges typically aren’t that long, either. One in five state drug offenders serves less than six months in prison, and nearly half (45 percent) of drug offenders serve less than one year.

That a prisoner is categorized as a drug offender, moreover, does not mean that he is nonviolent or otherwise law-abiding. Most criminal cases are disposed of through plea bargains, and, given that charges often get downgraded or dropped as part of plea negotiations, an inmate’s conviction record will usually understate the crimes he committed. The claim that drug offenders are nonviolent and pose zero threat to the public if they’re put back on the street is also undermined by a striking fact: more than three-quarters of released drug offenders are rearrested for a nondrug crime. It’s worth noting that Baltimore police identified 118 homicide suspects in 2017, and 70 percent had been previously arrested on drug charges.

Not only are most prisoners doing time for serious, often violent, offenses; they’ve usually received (and blown) the second chance that so many reformers say they deserve. Justice Department studies from 2000 through 2009 reveal that only about 40 percent of state felony convictions result in a prison sentence. A Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) study of violent felons convicted over a 12-year period in America’s 75 largest counties shows that 56 percent of the offenders had a prior conviction record.

Even though most state prisoners are serious and serial offenders, nearly 40 percent of inmates serve less than a year in prison, with the median time served about 16 months. Lengthy sentences tend to be reserved for the most serious violent crimes—but even 20 percent of convicted murderers and nearly 60 percent of those convicted for rape or sexual assault serve less than five years of their sentences. Nor have sentences gotten longer, as reformers contend. In his book Locked In, John Pfaff—a leader in the decarceration movement—plotted state prison admissions and releases from 1978 through 2014 on a graph. If sentence lengths had increased, the two lines would diverge as admissions outpaced releases; in fact, the lines are almost identical.

Getting these facts straight is important, especially since reformers unfavorably contrast the U.S.’s criminal-justice system with those of other nations—Western European democracies, in particular—with significantly lower incarceration rates. Because so few American prisoners are serving time for trivial infractions, aligning America’s incarceration numbers with those of, say, England or Germany would require releasing many very serious and frequently violent offenders. Yet many in the decarceration camp have been calling for just such a mass release. The #cut50 initiative, founded by activist and CNN host Van Jones, aims to halve the prison population. Scholars at the Brennan Center have called for an immediate 40 percent reduction in the number of inmates.

Such drastic cuts could produce significant crime increases, as communities lose the incapacitation benefits that they currently enjoy. Already, there’s no shortage of cautionary examples. In March, the New York Police Department released a montage of security-camera footage that captured ten gang members in East New York, a Brooklyn neighborhood, as they hunted down and killed a man in broad daylight. The chilling images show the victim, 21-year-old Tyquan Eversley (out on bail, facing a rap for armed robbery), running, as his armed assailants give chase. Eversley gets entangled in barbed wire after jumping a fence into someone’s backyard; one of his pursuers hurls what looks like part of a cinder block over the fence at him, as another points his gun over the top and fires five fatal rounds. The rock-slinging thug, according to the NYPD, is 25-year-old Michael Reid, who has since been identified and arrested. Reid, it was subsequently reported, had been recently released from federal custody and was wearing an ankle monitor at the time of the murder.

On the morning of May 25, 2019, according to prosecutors, two men—29-year-old Michael Washington and 23-year-old Eric Adams—drove down a residential street in the Austin neighborhood of Chicago, on the city’s South Side. Leaked surveillance video from a police camera showed the car as it passed a small group of people near a parked vehicle. One of them was an unarmed 24-year-old black woman, Brittany Hill, holding her one-year-old daughter, who waved at the car just before the vehicle’s occupants opened fire. Hill shielded her child from the bullets but was fatally wounded in the abdomen (just below where she was holding her child) and collapsed in the gutter. Washington was on parole at the time of the shooting, after serving time for a drug charge. Citing prosecutors, the Chicago Sun-Times reported that “Washington has nine felony convictions, including for a 2004 second-degree murder charge and a 2001 battery charge that was reduced from attempted murder in a plea agreement.” Adams, the second alleged shooter, also had an active criminal-justice status at the time of the shooting. He was on probation following a conviction for aggravated unlawful use of a weapon in 2018. In addition to the gun offense, Adams’s Chicago police record includes arrests for public-order offenses relating to marijuana possession and gambling.

With these three men, it’s not hard to argue that the criminal-justice system failed the public. All three had troubling criminal histories, signaling a general disregard for law and social norms. Yet they were deemed fit for parole or probation, resulting in two murders. In each case, both the perpetrators and the victims were black. Though the decarceration crowd continues to point to racial disparities in criminal enforcement, the data on criminal victimization suggest that the burden of any crime increase that accompanied large-scale prisoner releases would mostly fall on low-income black communities. Though black men constitute about 7 percent of the population, they accounted for 45 percent of America’s 15,129 homicide victims in 2017, FBI numbers show. A BJS study of homicides committed from 1980 to 2008 found that the victimization rate of blacks was six times that of whites. The black homicide-offending rate was about eight times the white rate. These differences, not racial animus, go a long way toward explaining the oft-lamented fact that black men are six times likelier to be incarcerated than white males.

Countless citizens on Chicago’s mostly minority South and West Sides have been victimized by offenders like Washington and Adams who’d gotten one too many “second” chances. A January 2017 University of Chicago Crime Lab study found that, of those arrested for homicides or shootings in Chicago in 2015 and 2016, about “90 percent had at least one prior arrest, approximately 50 percent had a prior arrest for a violent crime specifically, and almost 40 percent had a prior gun arrest.” On average, someone arrested for a homicide or shooting had nearly 12 prior arrests, the study noted—and almost 20 percent had more than 20 priors. You find more of the same in crime-wracked Baltimore. According to the Baltimore Sun, “85 percent of the 118 murder suspects identified by police [in 2017] had prior criminal records,” with nearly 36 percent being “on parole or probation” at the time of the alleged crime.

The serial offender isn’t just a problem in the highest-crime American cities. Data show that such crime has been occurring in urban jurisdictions across the country for years. The BJS study on violent felons convicted in large counties found that offenders on probation, parole, or released pending disposition of a case constituted 37 percent of those convicted during the 12-year period examined. With so many of the nation’s most serious crimes perpetrated by people with an active criminal-justice status—and with 83 percent of released prisoners arrested for a new crime within nine years of getting out—the safety benefits of incapacitation become startlingly clear.

Large-scale decarceration would also undermine the criminal-justice system’s retributive function, one of the four penological justifications for incarceration (with rehabilitation and deterrence joining incapacitation to constitute the other three). When I studied criminal law as a first-year law student, my textbook defined “crime” as conduct that, “if duly shown to have taken place, will incur a formal and solemn pronouncement of the moral condemnation of the community.” Incarceration, in other words, is more than just a way to protect society from wrongdoers; it’s also a key way that society condemns wrong and destructive behavior.

Small wonder that recent polling shows little support for decarceration. A 2016 Morning Consult /Vox poll found that 65 percent of respondents somewhat or strongly opposed “reducing sentences for crimes in general,” versus just 24 percent supporting such measures. The same poll reported only 32 percent of respondents strongly or somewhat supporting reduced sentences for nonviolent offenders likely to re-offend, and the support was lower still for easing sentences for violent criminals both likely and unlikely to commit further crimes.

America’s incarceration numbers would be even higher if more perpetrators of serious crime were apprehended. Most of the crimes that so many Americans believe—with good reason—should result in time behind bars go unanswered. Either the crimes aren’t reported or police prove unable to close the cases.

The FBI tracks and reports on eight “index crimes” committed in the United States. Half of those offenses are violent, and half concern property: murder and nonnegligent manslaughter, rape, robbery, aggravated assault, burglary, larceny theft, motor-vehicle theft, and arson. Since 2010, the U.S. has averaged about 1.2 million violent index crimes and 8.5 million property index crimes yearly. Keeping in mind that many similar crimes never get reported to the FBI, note that police clear just 46.8 percent and 18.9 percent of violent and property index offenses, respectively. Put differently, since 2010, about 5.1 million violent index crimes and 54.9 million property index crimes have gone unpunished—which works out to more than 7.5 million of these offenses yearly. Even assuming that certain criminals commit a disproportionate number of the crimes, one can say with confidence that, in any given year, a large number of people who should be in prison are not.

The U.S. incarcerates more people than any other nation, but international comparisons ignore important differences between other countries and ours. For instance, as is often pointed out by the same Democrats when discussing gun control, the U.S. has significantly higher murder and violent-crime rates than many other developed nations, and those rates of serious crime drive much of the disparity in incarceration—not low-level and nonviolent drug offenses. Likewise, the racial disparities in our prison population are a function of racial disparities in serious criminal offending, not systemic bias. Contrary to the decarceration narrative, most of those imprisoned in America are highly likely to reoffend; most prisoners have committed just the kinds of serious violations that most Americans agree should put them away; and plenty of criminals already walk our streets today who committed their crimes without detection, were released from prison or jail sooner than they should have been, or received too-light sentences, given the level of their actual infractions.

Democrats and their progressive allies are thus wrong that the United States has a mass-incarceration problem. While we should, of course, seek to improve the criminal-justice system’s imperfections, voters should resist drastic, far-reaching reforms. The real-world consequences of those reforms would be disastrous, especially for the nation’s most vulnerable neighborhoods.

Photo: Studies show that only about 40 percent of state felony convictions result in a prison sentence and that 56 percent of violent offenders had a prior conviction record. (JIM WEST/ALAMY STOCK PHOTO)