New Chicago mayor Lori Lightfoot took office in May facing major worries, among them the city’s woefully underfunded pensions, a projected $800 million budget deficit, and one of America’s highest large-city crime rates. Yet one of her first moves as mayor was to appoint . . . a chief equity officer. In her view, all of Chicago’s woes are smaller than its bigger one: it is “two cities,” where racial outcomes differ dramatically. The equity job’s purpose, as a local paper described the cabinet position, was to lead local government in “uprooting . . . inequity in just about every sector, including jobs, housing, economic development and education.” Lightfoot was inspired to create the new post partly by the Chicago Public Schools, which the year before had appointed its own equity officer and debuted a “Curriculum Equity Initiative,” which called for course work to be “fair across race, religion, ethnicity and gender; and culturally relevant with the mindful integration of diverse communities, cultures, histories and contributions.”

Many Americans probably have never heard of a “chief equity officer,” but it may be the hottest new job in municipal government. The emergence of the position is part of a broader movement to get local governments to look beyond the fundamental American ideals of equal treatment and opportunity and instead demand equity, which generally means the achievement of similar outcomes for all groups. While certain programs pursued under the equity banner—minority contracting set-asides, say—have been around for years, others are newer and more radical.

The equity movement presumes that any unequal results in society reflect structural or institutional racism, even when officials can’t identify any actual discrimination. To redress these purported inequities, the movement demands that every city department’s mission, and every major decision in local government, be looked at from a racial-equity perspective. In practice, this has meant mandatory bias training for municipal and school employees, in order to root out “policies that work better for white people,” in the words of one advocacy group, and laws passed in a number of cities that limit what employers can ask job applicants (about any past criminal history, especially), as well as other measures.

And equity promoters are pushing even more radical ideals, such as having municipalities pay reparations to minorities who’ve done poorly under local policies. Such revolutionary steps are apparently needed because, as a National League of Cities publication puts it, “no individual jurisdiction has achieved success when it comes to equity.” Only equal outcomes for all, however unlikely—or impossible—to achieve, will suffice. None of this bodes well for America’s urban future.

The equity crusade in local government started slowly about 15 years ago, in progressive cities like Seattle. Local activists there argued that minority residents were being left behind or, worse, actively harmed by the city’s economic growth, so politicians created the Race and Social Justice Initiative in response. As part of the effort, Seattle officials adopted a “racial tool kit” for government that required every city budget to go through a racial-equity analysis, measuring its impact on minority communities. City employees were also required to undertake training on “race, power, and implicit bias,” overseen by Seattle’s Office of Civil Rights. Other policies that boosters say have resulted from the initiative: a law banning firms from asking job applicants about criminal convictions; and a rise in the local minimum wage to $15 per hour.

The equity push has changed Seattle’s ongoing priorities. When, to take just one recent case, former mayor Ed Murray wanted to allocate $149 million in 2016 to build a modern police station that would replace an outdated, overcrowded facility, the city council demanded a racial-equity analysis of the project, which was subsequently canceled because of minority-community hostility.

The equity crusade has spread rapidly to other “woke” cities. Portland modeled its Office of Equity and Human Rights on Seattle’s effort. The office trains public employees in racial equity, which involves instructing them in the history of “public policies designed to favor whites over other races.” Portland has also developed an equity “dashboard” that publicly tracks the racial characteristics of the city’s government workforce. Austin created its equity officer position three years ago, after clamoring from community activists. A city task force recommends that Austin set aside a staggering $600 million to buy housing and reserve it for minority residents, consider reparations for minorities “affected by city codes or policies,” and grant housing subsidies to minority teachers to attract them to the public schools. In 2018, Baltimore joined the movement, with local lawmakers passing a measure that requires every city agency to “adopt a racial-equity lens,” notwithstanding the fact that two-thirds of the city’s residents, most of its elected officials, and many of its key bureaucrats are black.

The justification for this all-encompassing focus on race is a postmodern view on discrimination and prejudice that has migrated from universities into the public sphere. Its advocates contend that America’s major institutions remain deeply racist and that white (especially white male) privilege is the main driver of discrimination, even where no discriminatory behavior is evident. A Seattle government report, “Why Lead with Race,” is typical; it deems institutions as bigoted that “work to the benefit of white people,” as well as to “the benefit of men, heterosexuals, non-disabled people and so on.”

Some local equity initiatives take as their founding documents “equity-indicator” reports from organizations such as the City University of New York’s Institute for State and Local Governance, which simply measure group outcomes; any lag by minorities serves as prima facie evidence of bigotry. A report on Oakland, developed with support from the CUNY institute, for example, helped launch an “equity in Oakland” initiative. The report charted differences in outcomes by race in several areas in the city and concluded that higher graduation rates for white students, lower household incomes for blacks, and lower health-care coverage for Latinos show that “race matters” and that “troubling disparities by race” exist in the city.

“Many Americans have never heard of a ‘chief equity officer,’ but it may be the hottest new job in municipal government.”

The basic, but highly dubious, assumption behind these reports, and the equity movement generally, is that no possible behavioral differences among ethnic or racial groups might account for different life outcomes. Yet, as the eminent economist Thomas Sowell argues in his recent book Discrimination and Disparities, attitudes and behaviors that have nothing to do with bias can vary dramatically among cultural and ethnic groups over time and across societies. For example, he points out that the median age of Mexican-Americans is far lower than that of, say, Japanese-Americans; therefore, Mexican-Americans in the workforce tend to be younger and less experienced than Japanese-Americans, which can explain some of the variance in average income between the two groups—a factor that has nothing to do with discrimination.

Most equity studies avoid discussing obvious, documented differences of behavior. Sowell refers to black parents in the affluent suburb of Shaker Heights, Ohio, who, in the late 1990s, hired John U. Ogbu, a respected researcher on student achievement, to study why their kids weren’t performing as well as whites in the local school system. Ogbu found, among other things, that affluent African-American students were less likely to imitate their successful parents than were white students. “What amazed me is that these kids who come from homes of doctors and lawyers are not thinking like their parents. They don’t know how their parents made it. They are looking at rappers in ghettos as their role models, they are looking at entertainers,” Ogbu said at the time.

After Yale University’s Amy Chua published Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother in 2011, several researchers sought to test her claim that Asian parents demanded more of their children, a plausible explanation for their academic success. One study found that Asian students on average spent more than twice as much time studying as white peers, who themselves studied 60 percent more on average than black students. Asian-Americans create a particular problem for the equity movement’s views on white privilege: Asians now have higher incomes and better educational outcomes than whites, which seemingly wouldn’t be true if the system were rigged for whites. Faced with such facts, equity advocates proffer absurd reasons for why Asians do so well. In New York City, school personnel undertaking equity-bias training claim that the training supervisors told them that Asians were in “proximity to white privilege” and thus also “benefit from white supremacy.” Meantime, a National Education Association paper on “unconscious bias” says that teachers often stereotype Asian-Americans as “model minority” students, giving them an implicit advantage.

Rather than confront behavioral differences, bias training now labels attitudes and habits associated with America’s “strive and achieve” culture as unconsciously racist. Bias training used for teachers in New York City’s public schools includes a slide on the purported characteristics of “white supremacy culture” from the book Dismantling Racism: A Workbook for Social Change Groups. At the top of the list is the quest for “perfectionism,” which gives “undue focus to the shortcomings of someone or their work.” Other characteristics of white supremacy: a “sense of urgency,” “worship of the written word” (because it prioritizes documentation over relating to others), “individualism,” and “objectivity” (because it supposes that nonobjective viewpoints or emotions are bad). The presentation also dismisses the possibility of reverse discrimination, as it “equates individual acts of unfairness against white people with systemic racism which daily targets people of color.” (Of course, affirmative-action programs that disadvantage white and Asian students are, by definition, “systemic.”) As a student counselor in a Boston-area grammar school observed about that institution’s bias training, “What we’re trying to have teachers see here is that white people have benefited their whole lives from white supremacy.”

A training session for Seattle government workers illustrates how such ideas are helping to redefine behavior. Titled “Dropped or Pushed Out,” it presents employees with a scenario: an African-American 15-year-old girl, Gayl, has gotten pregnant after having sex with her 15-year-old Latino boyfriend Diego. Gayl tries to stay in school while raising the child; Diego goes to work at a gas station. When Gayl falls behind on her schoolwork, she meets with a white female social worker and her teacher Carlos, a Filipino. Sympathetic to her situation, the adults offer a range of programs to help, but they also say that they can do little if she doesn’t complete the required work. Carlos tells her, too, that Diego, recently busted for selling pot, “may be more part of your problem than a solution for you.”

After employees contemplate this little story, the training manual asks them: What are the instances of individual racism, institutional racism, and structural racism in Gayl and Diego’s predicament? The assumption is that some discrimination must be at work—though, by traditional definitions of the term, that’s not obvious. At the same time, the training program makes no effort to think about the behavior and choices of the young people, who might, after all, bear some responsibility for their problems.

The equity movement dismisses venerable American ideals of equality. “We’ve got to get beyond talking about equality and talk about equity,” says John Marshall, chief equity officer of the Jefferson County Public School System in Kentucky. He adds: “Equity is providing what is needed to do what is best.”

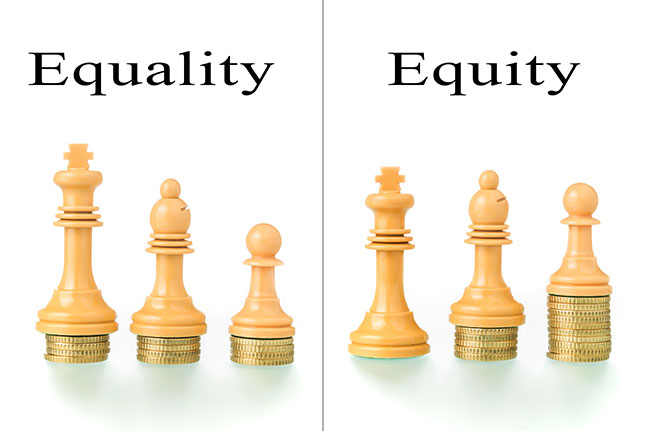

A cartoon used in training sessions for government employees illustrates this view. A panel, labeled “equality,” shows three boys of different heights trying to peer over a fence to watch a baseball game, with each standing on a box; the shortest boy can’t quite see over the fence. In the next panel, “equity,” the shortest boy gets two boxes, so that he can watch the game, too, while the tallest boy, who can see the game without a box, has none.

The cartoon implies that, with just a little benign help, everyone wins. But in the real world, achieving equity has become a rationale for taking from some for the benefit of others. Consider the push against public schools for exceptional students—especially where enrollment is based on merit criteria—for being too segregated. In New York, Mayor Bill de Blasio and his schools chancellor, Richard Carranza, have considered scrapping entrance-exam requirements for the city’s legendary elite high schools, including Stuyvesant (which Sowell attended in the 1940s as a poor kid living in Harlem) and Bronx Science, because high-achieving Asians have been securing a disproportionate number of the seats. The administration explored a new scheme that would offer places at these prestigious schools to students at every public middle school in the city, so that the elite schools would “look like New York City,” in de Blasio’s words. This shift would inevitably deprive Asian students of slots they’ve been earning through superior academic performance. Though parental backlash led de Blasio to reconsider the plan, Carranza raised the stakes when he said of the state law that originally established the admissions tests: “Anyone who is supporting that law—you are supporting a racist law.”

Elsewhere, pursuing equitable outcomes has involved separating young black and Latino students from whites and Asians and enrolling them in special schools. Jefferson County, to take one example, has opened “academies of color,” designed to get more minority students interested in science and technology careers. The curriculum has an Afrocentric orientation to “help reinforce the notion of self-worth” among students.

“Bias training now labels attitudes and habits associated with America’s ‘strive and achieve’ culture as unconsciously racist.”

Such efforts expose one of the most striking contradictions of the equity movement. On the one hand, reports of the type produced by the CUNY Institute for State and Local Governance or New York City’s School Diversity Advisory Group consider neighborhoods or schools that don’t mirror the racial diversity of the broader community to be segregated—and thus racist. Yet equity proponents also tout programs that segregate by race—not just with specialized academies but also with anti-gentrification efforts, the purpose of which is to freeze the racial or ethnic demographics of minority neighborhoods. In both cases, the movement fixates on skin color as all-important. “We’ve been told or conditioned to pretend to be colorblind,” the chief equity officer of Austin, Brion Oaks, said last January. “To do [equity] work effectively, we have to take that away.”

This single-minded racial focus guarantees that many of the equity movement’s programs are, or will prove, ineffective—or, worse, harmful. Consider measures restricting employers’ ability to ask job seekers about arrest and conviction records. They purport to protect minority applicants, assuming that too many of them are denied jobs based on their criminal histories. But research shows that firms that ask applicants such questions are more likely to hire minority men—perhaps because the businesses feel more secure hiring people whom they feel they know better.

The impetus to soften disciplinary standards in urban public schools so that fewer black and Latino kids get suspended or expelled, under the assumption that they’re treated more harshly than white and Asian students, has had truly disturbing results. One of the trendsetters of this approach was former St. Paul superintendent of schools Valeria Silva, who, a decade ago, began denouncing disproportionate minority suspension rates as an expression of a “punishment mentality” and—you guessed it—“white privilege” among teachers. During her tenure, schools dropped some penalties for student misconduct, stopped reporting all but the most violent offenses to local police, and returned special-education students with behavioral problems to general classrooms. Inspired by her example, St. Paul mayor Chris Coleman extended racial-equity initiatives throughout local government; soon, other cities across the country took similar steps.

In St. Paul schools, order collapsed. After several teachers were physically attacked by students allowed to remain in school, despite repeated earlier disciplinary infractions, teachers launched a petition demanding Silva’s dismissal. Parents—some of them minorities—complained that their children were being intimidated and threatened in school by bullying, unchecked students. Some parents who could afford a private education pulled their children from the public schools. In school-board elections, voters replaced members who had hired Silva, and in 2016, the reconstituted board forced her out. “I believe we were crippling our black children by not holding them to the same expectations as other students,” one African-American teacher, Aaron Benner, told the school board. (See “No Thug Left Behind,” Winter 2017.)

The equity movement’s reeducation agenda is sparking resistance in other locales. In New York, three former high-level white female administrators have sued the New York City Department of Education for $80 million, charging that they were demoted unfairly in favor of minority candidates as part of Carranza’s equity goals. “Under Carranza’s leadership, DOE has swiftly and irrevocably silenced, sidelined and punished plaintiffs and other Caucasian female DOE employees on the basis of their race, gender and unwillingness to accept their other colleagues’ hateful stereotypes about them,” the filing said. The suit alleges that the school system’s head of the Office of Equity and Access had said that whites “had to take a step back and yield to colleagues of color” and “recognize that values of white culture are supremacist.” Carranza himself reportedly told employees: “If you draw a paycheck from DOE . . . get on board with my equity platform or leave.”

On the other coast, Santa Barbara parents formed Fair Education Santa Barbara in a reaction against implicit-bias training (an approach based on an increasingly questioned theory that even when individuals don’t consciously discriminate, they do so unconsciously) and cultural-proficiency training now being given to local school personnel and to students. In April, the group filed a lawsuit claiming, as one parent put it, that the school system is advocating “intolerance, not tolerance.” The group included in its lawsuit a statement from a district parent who said that her son came home crying from school one day, saying that “he hated being white.” A former district teacher is quoted as saying that the equity material for students is “completely biased,” leaving students “visibly upset and not wanting to return.” Meantime, in the Kansas City suburb of Lee’s Summit, the school system’s first black superintendent, so enamored of equity that his Twitter handle was @EquitySupt1, was bought out of his contract after two controversial years of imposing equity mandates on teachers.

Despite such examples of failure and pushback, schools in places as varied as California, Illinois, Kentucky, New York, and Tennessee have had to change their discipline policies as a result of equity reports. Teachers remain among the government workers most frequently required to undergo equity training. But advocates are seeking to make even private-sector workers go through such training. A bill in the California legislature would require health-care employees to receive implicit-bias training or lose their medical licenses. Supporters say that the law is necessary because minority health outcomes lag those of whites, though there’s no evidence that bias among health workers is the reason. California is also looking at extending the training to judges, which could have a profound impact on the state’s courts. Equity-minded prosecutors elected in Philadelphia, Chicago, and other cities have already embraced the notion that the criminal-justice system is widely biased against minority offenders. These prosecutors have been leading efforts to decriminalize low-level crimes like fare-beating in subway systems and to reduce sentences, even for violent crimes. That trend would accelerate if large numbers of judges were to accept the claims of the equity movement.

The movement’s next target is likely America’s civil-justice systems. Already, plaintiffs’ attorneys have tried in several civil lawsuits to use the principles of implicit bias as grounds for discrimination claims. In a case stretching over a decade, attorneys representing a handful of Walmart female employees claimed that the retailer discriminated against all 1.6 million of the company’s female workers, based in part on the testimony of a sociologist who argued that the company had created a male-dominated culture where unconscious bias affected many management decisions. In 2011, the Supreme Court rejected that analysis as too general and lacking in “significant proof” of actual discrimination. Similarly, attorneys representing several African-American Iowa state government employees filed suit in 2006, claiming that the state “engaged in practices that resulted in a failure to maintain a diverse, nondiscriminatory workplace through its merit employment system.” The plaintiffs based some of the complaint on the theory of unconscious bias, including testimony from a psychology professor who viewed “implicit bias as pervasive and believed all people fall within a spectrum with explicit bias on one end and limited implicit bias on the other.” Ultimately, however, the state’s supreme court rejected the claims, arguing that attorneys needed to show proof of specific employment practices that were discriminatory.

It is opinions like this that the equity movement is striving to overturn by aggressively promoting the idea that society, including local government institutions, remains persistently discriminatory and that unequal outcomes are sufficient proof of bias. It’s an unfalsifiable idea: if you reject the contention that unseen bias is at work in your school system or court or city hall and demand actual evidence of discrimination, it’s either because you are a part of the supremacy culture or have been co-opted by it.

It’s a way of thinking that postmodernists used in our universities to disarm critics. Now, it’s being employed to spread postmodern theories of race and discrimination throughout local government. If it persists, city hall and public schools may never be the same.

Top Photo: urbazon/iStock