Does egregious police violence hurt community trust? A recent working paper from a group of economists led by Harvard’s Desmond Ang suggests the answer is yes, but readers should be skeptical.

The paper examines what it identifies as civilian behavior in the wake of George Floyd’s killing in Minneapolis last year, comparing changes in shootings (which skyrocketed) to 911 calls (which were flat or fell) across eight cities. This pattern, the paper’s authors argue, shows that “high-profile acts of police violence may severely impair civilian trust and crime-reporting.”

The authors’ research is still just a “working paper,” meaning it has not been formally peer-reviewed or published in a journal and so remains open to criticism and revision. But that has not stopped it from receiving laudatory attention in the press, including a standalone article in the Economist.

That media furor is too much, too soon. The are several methodological issues with the study’s attempt to measure civilian concern. In fact, the study may be detecting not a drop in public trust in the police but rather a decline in policing activity.

Most prior studies of the effects of police violence on public trust have looked at trends in civilian calls to the police (sometimes calls for service) before and after a triggering event. For example, an early paper studied the effect of the 2004 beating of Frank Jude by Milwaukee police and claimed to have identified a marked decline in 911 calls following the incident (this finding has been disputed).

But as Ang and his co-authors argue, 911 call trends are bound up with crime trends; it’s hard to disentangle a drop in reporting from a drop in the need for reporting. And because 911 calls are themselves a source of police information about offending, one can’t look at the ratio of offenses to 911 calls. To resolve this problem, the study uses data from ShotSpotter, the gunshot-detection system deployed in many cities, which, they argue, is an independent source of information about offenses.

These data show a precipitous drop in the ratio of calls to shots fired in the immediate aftermath of Floyd’s death: from 207 to 90, a 56 percent decline. As the authors show in a decomposition, the drop in the ratio of calls to shots fired was primarily the product of a spike in shots fired, as well as by a smaller decline in 911 calls.

But it’s unclear how useful it is to compare shooting incidents with all 911 calls, as there are vastly more calls than shots fired in any given city on any given date. A relatively small decrease in other kinds of calls—such as for traffic violations—can swamp even a doubling or tripling of shootings. We have no way of knowing whether an increase in gunshots did in fact lead to more calls reporting gunshots; if it did, then civilian reporting would not have meaningfully declined.

The paper’s authors deal with this objection by isolating 911 calls whose descriptions relate to “shots fired.” But this likely fails to capture many calls, because 911 data do not necessarily record “shots fired” incidents with this description. It also creates problems for the paper’s finding: as the authors show in the appendix, the ratio of gunshots to “shots fired” calls didn’t begin to fall below pre-Floyd norms until the first week of July, more than a month after Floyd’s death.

There’s another, deeper problem with the authors’ metric: they probably aren’t actually counting calls from civilians. Ang and his coauthors capture 911 calls using data on “calls for service” (CFS), which, they write, “are those that are initiated by citizens dialing 911.” But this is not true: calls-for-service data usually include all contacts with emergency dispatchers—both civilians and police, who regularly call in situations to central dispatchers so as to coordinate with other officers.

This problem crops up in many of the CFS data sets the study uses. For example, the CFS data published by the NYPD “includes entries generated by members of the public as well as self-initiated entries by NYPD Members of Service.” Cincinnati’s CFS data include “calls for service to emergency operators, 911, alarms, police radio and non-emergency calls.” San Diego’s include police-relevant activities like “investigating a crime that has already occurred.” It’s clear from a perusal of these and other public datasets that it is not possible to differentiate civilian calls from police calls.

This is a huge problem for a study that purports to measure how Floyd’s killing affected civilians’ willingness to call the police. As constructed, it actually measures both civilians’ and police officers’ propensity to call 911. When I asked Ang about this, he showed data that excluded calls related to traffic stops and patrols. But both police and civilians can report the same offenses.

This oversight explains the disparity between Ang’s research and my own. When I investigated the effect of Floyd’s killing on 911 calls, I isolated five cities—Minneapolis, New Orleans, Phoenix, Seattle, and Tucson—for which it is possible to identify civilian-initiated calls. None saw a meaningful decline.

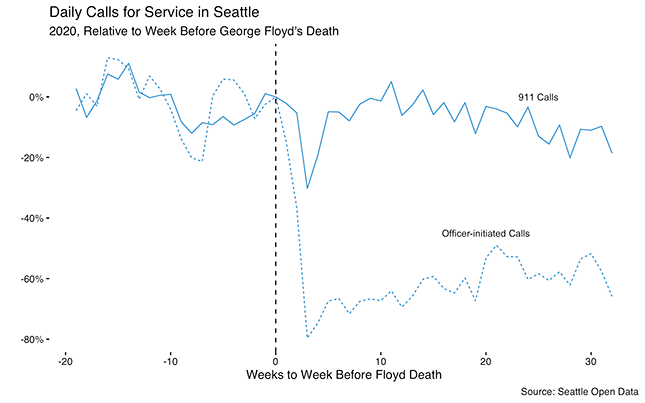

Where does the decline highlighted in Ang’s study come from? The answer, in fact, may be a drop in police calls, not civilian ones. In several of the cities I looked at, officer-initiated calls were the ones that declined. The results from Seattle are particularly stark:

These are results from just one city, but they are consistent with a broader decline in big-city policing capacity (in terms of manpower, proactivity, and other factors) following Floyd’s death. The paper, in other words, may not have been picking up a decline in trust in police but a decline in police activity: the Minneapolis effect.

Of course, it might be the case that—in contrast with evidence from 27 other high-profile cases of police brutality—Floyd’s death really did spark a dramatic drop in civilian engagement. But the working paper doesn’t prove that proposition. Media outlets should stop suggesting that it does.

Photo by JEWEL SAMAD/AFP via Getty Images