Black Lives Matter, though less prominent in the headlines of late, continues to be quite a growth story. What began in 2013 as a hashtag propagated by a few activists and academics rapidly grew into a nationwide protest movement and then into an institutional establishment, with local chapters around the U.S. and even a few abroad. With lavish funding and generally supportive media attention, the BLM network has become the progressive Left’s primary organ of antiracism activism. Now it seeks to sustain and expand upon that success. In its most ambitious venture yet, the group has moved beyond the streets and into the nation’s public schools.

No one should be surprised. As BLM statements repeatedly make clear, the movement has always linked the charges of police misconduct that brought it into existence with a comprehensive critique of the American polity. “State violence” against blacks “takes many forms,” the BLM network’s “About us” statement declares. The first plank of a widely publicized platform issued in 2016 demands “an immediate end to the criminalization and dehumanization of Black youth,” including “an end to zero-tolerance school policies and arrests of students, the removal of police from schools, and the reallocation of funds from police and punitive school discipline practices to restorative services.” BLM founder Opal Tometi heads the list of signatories of a 2018 letter urging teachers to support a “new uprising for racial justice” in the nation’s schools.

Neither Tometi nor BLM’s other two founders, however, initiated the latest campaign. In keeping with activists’ pride in their network’s decentralization—a self-conscious departure from the top-down organizational model that they ascribe to the civil rights movement—the present venture is akin to a franchising operation, with local cells of teachers’ union activists as the operators. K–12 educators sympathetic with the movement have successfully promoted the “Black Lives Matter at School” program, bringing its activist spirit and ideology into a growing number of secondary and even elementary classrooms.

One figure in the drive stands out: Jesse Hagopian, a teachers’ union activist and high school ethnic-studies teacher in Seattle. A veteran advocate for increased public school funding and opponent of high-stakes standardized testing, Hagopian first came to public notice in 2011, when he and fellow demonstrators tried to pull off a “citizens’ arrest” of the Washington state legislature, on the grounds that lawmakers had failed to comply with a state constitutional mandate to fund the schools adequately. For Hagopian, the funding and testing issues are tributaries of his main interest, the combating of “institutional racism”—a cause to which he was first awakened, he reports, by his course work in media studies and critical race theory at Macalester College, a notoriously left-leaning liberal arts school in St. Paul, Minnesota.

The catalyzing event for Hagopian’s BLM work occurred in September 2016. A local group, led by a student support worker, staged a demonstration called “Black Men Uniting to Change the Narrative” at Seattle’s John Muir elementary school. A decision by the school’s teachers and staff to wear BLM T-shirts in solidarity sparked public controversy, which, in turn, prompted a teachers’ union subgroup, Social Equity Educators (SEE), to plan a citywide event, “Black Lives Matter at School Day,” to be held a few weeks later. Endorsements flowed in from the Seattle Education Association (SEA), the Seattle School District administration, and the local NAACP branch. Thousands of BLM T-shirts were sold, and SEE and SEA disseminated BLM instructional resources to teachers and parents. According to participants’ chronicle of events, on October 19, the appointed day, “thousands of educators . . . reached tens of thousands of Seattle students and parents with a message of support for Black students and opposition to anti-Black racism.” The coauthors of that chronicle, Hagopian and local education professor Wayne Au, enthused over Seattle’s institutional and parental support “for a very politicized action for racial justice in education.”

Seattle was only a beachhead. Au circulated a letter that within days had gained the support of 250 education professors across the country. The parallel letter of support signed by Tometi received the signatures of big-name progressives, including Melissa Harris-Perry and Jonathan Kozol. News of the Seattle event spread, inspiring like-minded teacher groups in Philadelphia and Rochester, New York, to plan similar BLM days—or, in the Philadelphia case, a full BLM school week, in 2017.

Activist teachers formed a national committee and prevailed on the National Education Association to adopt a resolution of endorsement. Thus was conceived the BLM at School National Week of Action, to be held annually the first week of February to set the tone for Black History Month. The following year, school districts in more than 20 major cities, including New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, Washington, D.C., Boston, and Seattle incorporated BLM at School Week into their curricula. This past February, amid favorable publicity, school districts in more than 30 cities and counties participated.

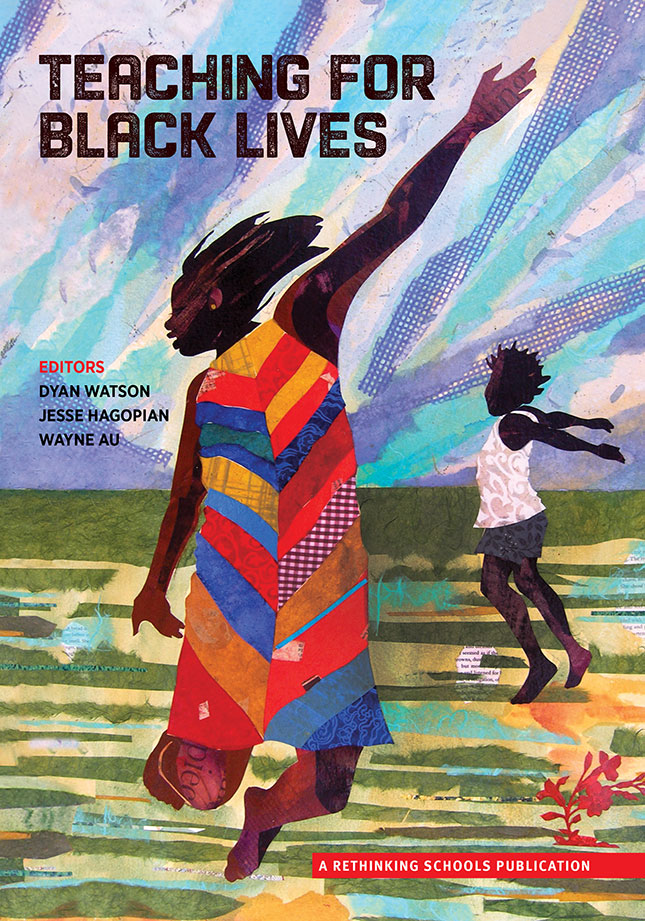

Hagopian, Au, and education professor Dyan Watson provide a pointed description of the movement’s goals in their introduction to Teaching for Black Lives, a textbook meant for use in the BLM at School efforts. The objective, they write, is to show how educators “can and should make their classrooms and schools sites of resistance to white supremacy and anti-Blackness, as well as sites for knowing the hope and beauty in Blackness.” That ambition, in their view, cannot be satisfied by the opportunity to shape instruction for just one week per school year. As becomes clear in organizers’ statements of principles and demands, as well as in the burgeoning mass of instructional material that participating teachers have contributed (including lessons for every grade level), the ultimate objective is to catechize the nation’s students, from kindergarten through high school, in BLM’s race-based vision of the world.

Profiles of Hagopian leave the impression of a genuinely bighearted man, devoted to his students’ well-being. Yet those who believe that being antiracist today means supporting the BLM agenda should consider more carefully the ideas that the movement is urging us to embrace.

In the BLM statement “What We Believe,” which includes the “13 guiding principles” from which the school curricula are developed, one finds affirmations reminiscent of the best of the black freedom movement of a half-century ago: “We acknowledge, respect, and celebrate differences and commonalities”; “We work vigorously for freedom and justice for Black people and, by extension, all people.” Likewise, in the National Black Lives Matter in School Week of Action Starter Kit appears this comforting guidance on how to discuss BLM with young children:

We can also mention the movement as a group of people who want to make sure that everyone is treated fairly, regardless of the color of their skin. We can say . . . “The Civil Rights Movement, with people we know about, like Martin Luther King, Jr., and Rosa Parks, worked to change laws that were unfair. The Black Lives Matter movement is with people who want to make sure that everyone is treated fairly, because, even though many of those laws were changed many years ago, some people are still not being treated fairly.”

Looking beyond those relatively anodyne representations, however, one finds unambiguous expressions of social-justice extremism. Among BLM’s 13 principles, for instance, are various commitments to intersectionality—that is, the focus on overlapping categories of racial, gender, or sexual victimization. BLM dedicates itself to dismantling “cisgender privilege,” “freeing ourselves from the tight grip of heteronormative thinking,” and “disrupting the Western-prescribed nuclear family structure requirement.” The Starter Kit section on teaching young children declares: “Everybody has the right to choose their own gender by listening to their own heart and mind. Everybody gets to choose if they are a girl or a boy or both or neither or something else, and no one else gets to choose for them.”

BLM’s teaching about race is no less radical. The first sentence of the introduction to the Teaching for Black Lives textbook reads: “Black students’ minds and bodies are under attack.” Anecdotes of abusive treatment follow, preparing the central thrust of the BLM-at-school pedagogy: “The school-to-prison-pipeline is a major contributor to the overall epidemic of police violence and mass incarceration that functions as one of sharpest edges of structural racism in the United States.” The stoking of readers’ anger continues with this distorted characterization of the galvanizing event for BLM’s street protests: “In August of 2014, Michael Brown was killed in the streets of Ferguson, Missouri, his body left in the streets for hours as a reminder to the Black residents in the neighborhood that their lives are meaningless to the American Empire.”

Instances of such incendiary rhetoric recur in the recommended instructional materials. The animating idea throughout is that African-Americans, intersecting with a familiar roster of other aggrieved identity groups, face systemic oppression, as they always have in America—even today, 50 years into the post–civil rights era. For all such groups and their “allies,” the proper relation to society must therefore be one of opposition, and a primary function of the education system must be to instruct students in the rationale, means, and ends of resistance—the more radical, the better.

Commonly recognized eminences such as Frederick Douglass and Martin Luther King, Jr., may be honored for their resistance, so far as it extended, but the real heroes, according to BLM’s pedagogues, are the most extreme figures and factions in the history of black protest. Presenting U.S. history as an unbroken chain of oppression, BLM’s instructional materials endeavor to burnish the reputations of black nationalists and socialists including Malcolm X and the Nation of Islam, Black Power founder Stokely Carmichael, and the leadership of the Black Panther Party. In a chapter devoted to them in Teaching for Black Lives, the Panthers are characterized as “one of the most important human rights organizations of the late 1960s,” a group whose “revolutionary socialist ideology” is credited for inspiring noble endeavors to provide decent housing, education, and health care to impoverished black communities and whose history “holds vital lessons for today’s movement to confront racism and police violence.”

“The real heroes, according to BLM’s pedagogues, are the most extreme figures in the history of black protest.”

Perusing the recommended BLM instructional materials, one confronts many questions—commonly pressed in the form of accusations—concerning race- and gender-related injustices in America. Undertaken in a spirit of genuine openness, such questioning would be perfectly consonant with the classical liberalism of America’s Founders, exemplifying a Madisonian mistrust of majority factions or a Jeffersonian vigilance against encroaching government. To assess the quality of the conversation that BLM’s enthusiasts would initiate in the schools, though, one must also consider questions not recommended for student reflection. Even as Teaching for Black Lives extols the Black Panthers as human rights champions and decries their persecution by law enforcement, for instance, it ignores the real-world track record of the revolutionary socialism that the Panthers espoused, leaving students to suppose that socialism in practice meant nothing more than feeding, educating, and healing the needy. Likewise, BLM advocates solicit no inquiry into the despotic character of Panther leader Huey Newton, a man prone to fits of psychopathic violence.

In their zeal for intersectionality, in turn, BLM’s leaders and pedagogues announce their determination to “disrupt the Western-prescribed nuclear family structure,” while withholding any suggestion that students inquire into the effects—above all, on children—of fatherlessness, rampant among disadvantaged black and Hispanic-Americans, and increasing among disadvantaged whites. Likewise, urging students to affirm fluidity and autonomy in gender identities, they acknowledge no questions concerning the physical and psychological risks associated with gender-reassignment therapies, nor any reason to wonder what will remain of antidiscrimination protections for women if subjective choice overrides the biological fact of sex. Nor do they invite students to wonder, on the same grounds, whether racial identity can also be a matter of human will—and, if so, what would remain of protections against discrimination by race.

The most conspicuous unasked questions pertain to the movement’s core allegations about police abuse and the “school-to-prison pipeline.” Students, likely to be frightened or incensed by charges of an epidemic of antiblack violence perpetrated by law enforcement and of systematic bias practiced by school authorities, are not encouraged to ask—indeed, are discouraged from asking—such questions as the following, which I propose:

What were the results of the Obama administration directive, based on the allegation (propagated by BLM) of antiblack discrimination in schools’ disciplinary policies, that schools cease enforcing disciplinary rules that had a disparate impact on racial- or ethnic-minority students? Did classrooms become more orderly and conducive to learning, or less so?

With respect to claims of an “epidemic” of racially biased killings—“extrajudicial executions”—of black people by police officers, what do available data reveal of the absolute numbers of police deployments of deadly force in recent years? What do they reveal about the numbers of people shot by police, relative to the numbers shot by non-law-enforcement, “private-sector” perpetrators?

What do the data reveal about the numbers of black suspects shot by police relative to nonblack suspects? How do those numbers compare with the numbers of serious crimes committed by blacks relative to those committed by nonblacks?

Since the rise, beginning in 2014, of public accusations of racial bias in police officers’ deployment of violent force, how have officers responded in the policing of high-crime areas? What has happened to the violent-crime rates in those areas in that time period?

What evidence warrants BLM activists’ sweeping allegations of a U.S. “war against Black people,” of America’s “systemic violence against Black people,” of “a world where Black lives are systematically and intentionally targeted for demise,” and the like?

Perhaps those responsible for BLM at School Week avoid such questions because they presume the answers, or view the questions as biased. Whatever their reasons, were they to confront those questions squarely, they would discover what readers of City Journal likely know—that empirical evidence radically complicates their view of the American polity as an enduring antiblack despotism.

A fair-minded inquiry would note recent findings that a relaxation of school disciplinary policies does not improve outcomes, either in classroom orderliness or student performance—to the contrary. With respect to the charges of abusive and biased policing, BLM sympathizers willing to confront the evidence would discover that homicides by private actors vastly outnumber deployments of deadly force by police officers, and the vast majority of those involve perpetrators and victims of the same racial groups; that the majority of those killed by police were either armed or violently resisting arrest; and that the percentages of police killings that involve black suspects are roughly proportionate to the percentages of violent crimes by black offenders, while black citizens are much more likely than those of any other racial group to be victimized in violent crimes. They would also discover that murders in many of the nation’s large cities significantly increased in 2015 and 2016, reversing a long-running decline. The increase was coincident with the rise of BLM antipolice protests; some researchers have attributed the upsurge to the protests’ demoralizing effects on police.

Given these data, if the propagators of BLM’s vision of racial justice decline to address seriously the questions that that vision raises, they would leave their movement exposed to the most challenging question of all: Which black lives really matter to BLM—those of the law-abiding or the lawless, the peaceful or the violent, the orderly or the disorderly?

For many, what legitimates BLM’s bid to shape the minds of students is the notion that the group is the rightful heir of the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s. Despite BLM leaders’ invocations of King and the “beloved community,” that notion is profoundly mistaken.

BLM does have a valid claim on a portion of the past century’s black freedom struggle—but it is the portion associated with the movement’s derailment, not its lasting successes. Whereas the old, and now broadly revered, African-American protest tradition, which reached its culmination in the classical phase of the civil rights movement, ultimately succeeded because it aimed to complete America, BLM’s explicit objective, inspired by the Black Power factions of the late 1960s, is to transform America. The trouble with BLM is that its activists and theoreticians cling uncritically to an ideologically blinkered rendering of America as an empire of seemingly incorrigible bigotry. That vision of America is a hallucination that, propagated in schools, promises to lower rather than to lift the life prospects of vulnerable young people.

In the preface to his biography of Frederick Douglass, Booker T. Washington remarks: “Douglass’s career falls almost wholly within the first period of the struggle in which [the racial] problem has involved the people of this country—the period of revolution and liberation. That period is now closed. We are at present in the period of construction and readjustment.” Washington published those words in 1906, when Ida B. Wells had been loudly engaged for over a decade documenting the rising incidence of antiblack lynchings, especially in the former Confederate states. Washington’s judgment was certainly overstated, likely deliberately so; he knew that the work of liberation was far from complete. Even so, in his mapping of the stages of progress, one finds a farsighted wisdom. For African-Americans, as for all others, the essential work of moral and political life is twofold. One element is resistance to injustice—revolution and liberation, as Washington put it, the altering or abolishing of unjust political or social orders. The other is construction, the task of establishing justice and virtue. The first stage, Washington advised, must be conceived as instrumental and transitory; it must at some point give way to building.

Washington’s remark contains a subtler suggestion as well. The work of construction—the cultivation of the virtues requisite to material success, citizenship, and moral health, and the creation and preservation of the institutions that make them possible—must be undertaken before liberation has been fully achieved, because full liberation is achievable only by means of these virtues.

The Washingtonian wisdom doesn’t deny that reasons for protest occur in post-civil-rights-era America. Serious misconduct by government officials does take place; law-enforcement officers’ deployments of violent force, while often justified, are sometimes not justified. Men are not angels; angels do not govern men. The need for Madisonian and Jeffersonian vigilance is permanent. But the ethos of protest, taken to excess, is debilitating, too often pursued to the exclusion, and even denigration, of the constructive virtues.

For BLM, black Americans are frozen in time, confined in a revolutionary moment in which, now as ever, the one thing needful is protest; the work of liberation is the only work; the heroes of resistance are the only heroes. The supposition seems to be, to adapt Allan Bloom’s phrase, that the liberated will somehow possess all the virtues, absent any deliberate effort to nurture them.

The heroes of righteous protest, those who labored tirelessly and ingeniously over the course of many decades to bring down slavery and governmentally enforced discrimination, are not the only heroes. Nor is their preeminence as honorees equally suitable for all seasons. Where are the justice and wisdom in propagating, in 2019, a pedagogical vision that confines African-Americans’ life possibilities to the activities of protest and resistance? Rather than beglooming students’ imaginations with oppression stories—as though the main object of their education should be to swell the ranks of street protesters, classroom agitators, community organizers, diversity consultants, and the like—shouldn’t a genuinely antiracist education inspire them with stories of positive accomplishment, drawn from authors ranging from William Wells Brown to W. E. B. Du Bois to Carter Woodson to Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, highlighting the fact that, throughout U.S. history, African-Americans have been inventors and discoverers, producers of great works of art, leaders in industry and commerce, and founders and sustainers of schools and churches and businesses and other institutions of social uplift?

Now, above all, as the nation’s schools devote earnest effort to the incorporation of African-Americans’ history into their curricula, it is a moral, an intellectual, and a civic imperative to honor the wisdom of Booker T. Washington and of similar unsung others. It is time to honor the builders.

Top Photo: The cover of the textbook used as part of the BLM curriculum, which seeks to make “classrooms and schools sites of resistance to white supremacy and anti-blackness.” (COURTESY OF THE PUBLISHER, RETHINKING SCHOOLS)