Educational Pluralism and Democracy, by Ashley Rogers Berner (Harvard Education Press, 200 pp., $35)

Should all parents be free to choose the school they believe is best suited to their children—and should that choice be supported by public funds? Does the government, whether state or federal, have an obligation to see that all schools offer an academically strong curriculum, including core concepts necessary to the goal of preserving “the full history of the United States” in a way that honors “cultural minorities while simultaneously inculcating democratic values”?

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

Johns Hopkins professor Ashley Rogers Berner has been exploring these questions since the publication of her 2017 book, Pluralism and American Public Education: No One Way to School. In her latest book, Educational Pluralism and Democracy, she seeks to chart a way forward for the adoption of curricular reform alongside the growing state-level adoption of universal school choice. It’s a daunting task, as she concedes: “We seem currently betwixt and between, with red states expanding access, blue states removing it, and curriculum wars ongoing.”

Berner defines educational pluralism as “a way to structure education in which the government funds a wide variety of schools but holds all of them accountable for academic results.” Five of the eight states that recently adopted universal choice require participating schools to follow a state testing mandate, which seems to meet this definition.

Berner has a larger vision, though, one equally hard to argue against--and to realize. She wants to see all schools in a pluralistic system offer a curriculum rich in content and not limited to the Common Core’s “twenty-first century skills,” focused on reading, mathematics, and critical thinking. The skills emphasis constrained what schools taught, as states had to follow federally required testing programs in English and mathematics. What was tested became what was taught.

Berner and her Johns Hopkins colleagues have developed a system, Knowledge Map, that measures the value of educational curricula and materials and tries to answer the question: “What knowledge would kids gain if they read this material?” To date, they have applied it to more than 70 English language arts (ELA) and social studies curricula. Analyzing such curricula created by school districts, they found that the vast majority did not build student knowledge or consistently use high-quality sources; their assessment of 12 published ELA curricula found “very different levels of knowledge building in key domains.”

This work informs Berner’s recommendations for how state education officials, individual schools, and school networks should provide the content-rich curriculum that she argues all students should receive in a pluralistic system. She lauds Louisiana for developing ELA exams aligned to two of the state’s commonly used curricula. These middle school exams do test skills, but they also urge students “to think deeply about specific sources they’ve read in class, integrate new but related content thoughtfully, and synthesize ideas in an end-of-grade essay.” These exams followed Louisiana’s earlier effort to ensure that schools chose high-quality curricula and learning materials.

Berner concludes with a discussion of how educational pluralism can become the norm in the U.S. It will require a cultural shift, she argues, pointing to two historical examples: the decades-long campaign for same-sex marriage in the U.S., and the nineteenth-century abolitionist movement in England, which led to the outlawing of slavery.

Berner rightly acknowledges the need to build consensus on educational content, shifting from a movement led by policy elites to one that organizes across sectors and builds bipartisan alliances, engaging local parents, community leaders, and clergy. I’ve been involved in the second type of effort; it is incredibly hard work, but also effective and rewarding. Such endeavors work best when focused on specific problems.

The cultural changes that Berner desires are vast and thus harder to accomplish. Berner’s first three recommendations are feasible: find the right message, build strong networks, and address practical issues together. Her fourth is less so: forge a grand political bargain. One model she offers is Illinois’ 2017 adoption of a tax-credit program to fund scholarship programs for private school choice, with the requirement that schools accepting scholarships must use the state’s annual assessment system. This isn’t a great example: it lacked the deep curricular reforms that Berner seeks, and, more importantly, the program did not last. Illinois ended it legislatively in 2023.

Berner seems to see educational pluralism as an alternative to the argument that school choice alone is enough. I came away from her book better informed but skeptical about her idea that the key question is how to build a political consensus from outside the schools. Rather, we should be asking ourselves what type of system will allow schools themselves to strengthen their curricula: is it a system in which the state education department and teachers’ unions call the shots, or one that gives parents the power of the purse through universal school choice? I lean toward the second answer. The universal-choice states have created an environment in which new and innovative school networks can form, using tools like Berner’s Knowledge Map to assess the quality of their educational content. If such a system spreads, perhaps a broader public discussion about educational content and quality would follow.

I also wonder about how technology, social media, and artificial intelligence might be rendering moot the debate about choice versus curriculum. If students aren’t reading books, and if AI is facilitating cheating on school assignments, then even the imposition of strong curricula will not result in real learning gains. And that means we face even bigger challenges.

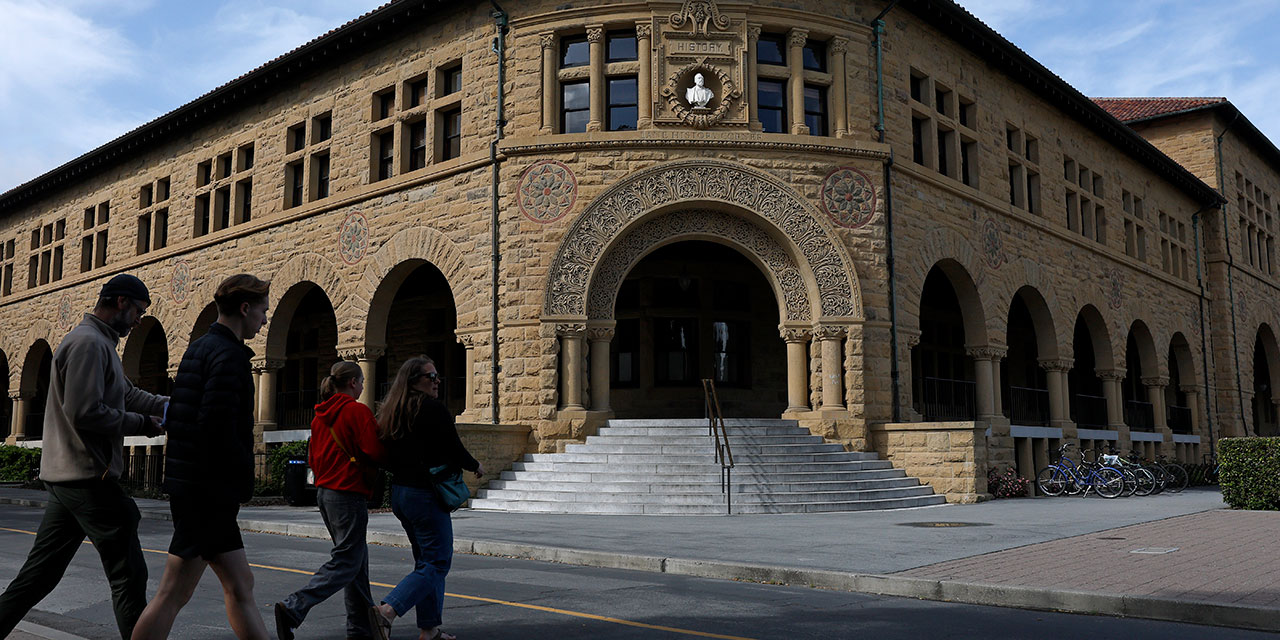

Photo by Allen J. Schaben/Los Angeles Times via Getty Images