Conservative reformers greeted President Bush’s late-April proposal for “progressive indexing” of Social Security benefits with dismay—and prominent conservative leaders haven’t said much about it since. They’re wasting an opportunity. Yes, Bush’s proposal was meant as a giveaway to liberals—a politically calculated trade to win their support for reining in Social Security’s unsustainable growth. And it’s a fair deal, provided that conservatives get what they’ve always wanted from reform: personal accounts within Social Security, to entice millions of middle-income Americans to join the investor class.

The president’s progressive-indexing idea is hardly revolutionary. It represents a change in degree, not in philosophy. Social Security benefits are already a radically “progressive” income-transfer program, in which low-wage earners make out, relatively speaking, much better during retirement than do middle-income and top earners.

Unlike the graduated income tax, which imposes a higher rate on higher earners, Social Security levies the same rate on all earners (within a $90,000 annual earnings cap) during their working lives. But the system pays back higher-income participants at lower rates when they retire. Workers get more “credit” for the payroll-tax payments they make on the first few hundred dollars they earn each month, and that credit drops precipitously for additional earnings.

For Social Security purposes, politicians already define high earners as those who make just $45,400 a year. So all middle-income earners underwrite a delayed income-transfer system to the poorest earners. In other words, this is already a tightly compressed welfare system. Though middle-income folks don’t pay much attention to how much money they will eventually lose in retirement income to lower-income retirees, conservative leaders shouldn’t be shy about reminding them that Social Security, despite the myths surrounding it, is by no means a fair retirement program.

Though the president’s proposal is still vague, its basic elements are clear enough. Let’s start with the bad part before looking at what makes the overall scheme so attractive, and then consider how its underlying principles can best be realized.

Bush would pare back Social Security’s future payouts to middle and top earners, giving a huge relative boost to retirees whose lifetime earnings were low. Right now, the Social Security Administration determines a new retiree’s initial benefit according to a formula based on how quickly U.S. wages increased during that worker’s career. The president would like to preserve that formula for the bottom 30 percent or so of earners. But for higher earners, the initial benefit would be based on how quickly prices, rather than wages, increased during a worker’s career—in other words, at the rate of inflation. Since wages usually rise more quickly than prices, future benefits for lower-income people would grow much faster over time than would benefits for middle- and higher-income people.

This doesn’t sound like enlightened reform, and understandably it has annoyed some conservatives. Columnist George Will objected on ABC’s This Week in late April: “So what [Bush is] doing is making Social Security less and less relevant to a majority of the American people. You’re stigmatizing it . . . by . . . means-testing Social Security so it becomes a poverty program.” Republican senator George Allen of Virginia worried that the plan would “reduce the retirement security for . . . middle-income working people.” Cato Institute senior fellow Alan Reynolds warned, “Any Social Security ‘reform’ that [is] increasingly generous to those who paid the least in taxes would be increasingly perceived as grossly unfair and therefore politically untenable.”

But they’re forgetting the good news in Bush’s proposal: personal accounts, which will make Social Security more relevant to middle and upper earners, not less, since it will give them the ability to save for a middle-class retirement within Social Security, not despite it. Reform without personal accounts, or with tiny personal accounts for top earners, isn’t real reform.

With the establishment of personal accounts, progressive indexing won’t mean a benefit cut for middle and upper earners. In its entirety, Bush’s proposal would simply shift massive future liabilities from the government to the free market.

Here’s how it would work. Social Security benefits currently rise faster than inflation, because, as noted, growth in future benefits keeps pace with average wage increases, and wages historically rise faster than prices. The Social Security Administration’s actuary estimates that wages will keep rising slightly over 1 percent faster than prices each year for the next 50 years or so.

Wages rise faster than prices because productivity growth and technological advances, not just inflation, push them higher over time. American workers produce more each year with less capital and less time, so their wages rise while prices stay down. Retirees now see the results of that wage growth in their Social Security checks—but the burden is entirely borne by younger taxpayers who must fund that growth in future benefits, and that burden is becoming unsustainable.

Personal accounts within Social Security would let current workers continue to benefit from those same economic advances. After all, the same worker productivity that allows wages to rise also shows up in robust corporate profits, which in turn fuel strong stock- and bond-market returns. Future retirees would reap those returns through their personal accounts, where some of their tax dollars would go to building up nest eggs for retirement.

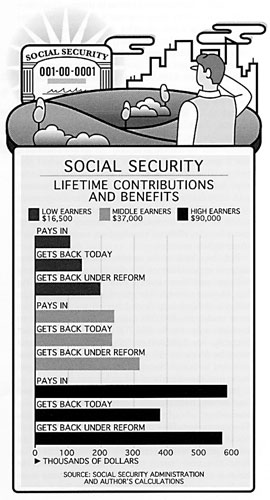

Just compare the returns on Social Security of three hypothetical young earners under the way things are supposed to work now—though remember, the current system is unsustainable—and then under City Journal’s fleshed-out version of Bush’s still-sketchy proposal.

A nurse’s aide who earns about $16,500 a year, or slightly less than half of the average American wage, over, say, a 44-year career, contributes about $106,900 to Social Security under today’s system (in today’s dollars, but adjusted for 1 percent real wage growth). In return, if she retires at 65, in 40 years or so, she can expect to receive an $11,900 annual benefit during her golden years. If she lives for 12 more years, it comes out to about $142,800. In today’s dollars, she’ll get back 34 percent more than what she put in (though without reform, the Social Security Administration estimates the government will only have the money to pay her 74 percent of that). This isn’t terrible, but she’d earn as much or more investing her money in government bonds, without needing an income transfer from richer earners.

But then look at the senior manager who earns today’s equivalent of six figures straight out of college and then every year thereafter during his 44-year career. He pays about $583,300 in today’s dollars into Social Security over his lifetime under the $90,000 cap. But he can expect to receive only about $31,700 a year from Social Security—or $380,400 in total, if, like the nurse’s aide, he lives for 12 years after he retires. How relevant is Social Security to him, when he’ll get back just two-thirds of what he put in?

But forget the extremes: look at a unionized bus driver, who steadily earns the average American wage, about $37,000 a year, throughout his 44-year career. He contributes about $239,800 to Social Security during those years—and, for 12 years after retirement, can expect to receive $19,500 a year, for a total of $234,000 back. He loses a tiny bit of all that money each year over all those years, but his adult children get nothing back for all his hard work should he die a widower at 70. (Of course, if he dies early and leaves behind a wife who made less than he did during her own working years, she’ll receive a survivor’s benefit.) This is a far cry from the myth of a safe retirement program designed for and embraced by the middle class.

But now let’s throw well-structured personal accounts into the mix. Our $90,000 high-achiever is still sending $583,300 to Social Security—but he’s allowed to invest a full one-third of his annual contributions in a personal account. At an average 5.2 percent annual return, he’s got $687,500 in his personal account upon retirement. He’s got to give some of that back to Social Security, under a complicated formula to be used in conjunction with personal accounts to make up for the money that was diverted from “the system” all those years—but even after accounting for that “clawback,” he’s got $300,700 in the bank.

Let’s say he earns 3 percent interest on that sum during retirement, or $9,000 annually. He could choose to withdraw that amount each year to add to his traditional Social Security benefit while barely touching the principal—and upon his death, his legacy would be more than a quarter-million dollars to his adult children or young grandchildren. The income from his personal account, conservatively invested, nearly replaces the $9,300 or so lost each year from his traditional benefit after the switch to progressive indexing (as the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities estimates the loss). Plus, that nest egg survives him and could help send two grandchildren to college. He finally has a stake in Social Security.

The same holds true for our average-guy bus driver, who could expect to leave $123,600 to his heirs, even if he chooses to supplement his traditional Social Security benefit with a modest withdrawal of income from his personal account of an extra $3,700 a year. His traditional benefit would be cut by about $3,300, to about $16,200 a year. But the extra income from the personal account, not to mention the inheritable asset, would more than make up for the cut. All told, including the personal account, he would be getting back 33 percent more than he put in.

And even our poorest earner, should she elect to invest in a personal account, could leave $55,100 to her own children upon her death, assuming she has chosen to withdraw her 3 percent interest of nearly $1,700 a year from that personal account to supplement her traditional retirement benefit—which, remember, hasn’t been cut. This is an invaluable sum to a poor worker who has lived hand to mouth all her life. Just like the rich, she has finally built up some family capital to pass to future generations—even if, since the poor have a shorter average life span than the rich, she doesn’t live to collect many years of her traditional benefit.

No, decent market returns are not guaranteed. But if free markets work at all, that superior benefit should be waiting for these workers when they retire. Moreover, if personal accounts don’t keep growing over the next 75 years because corporate profits have stalled, we’re all in trouble. Wealth creation, tax payments, and government revenues would shrink. And if corporate America is doing that badly, wages wouldn’t rise, Social Security benefits under the current formula would stagnate, and government wouldn’t have the wherewithal to pay them anyway.

Bush’s plan for personal accounts doesn’t envision letting Americans gamble their Social Security money on, say, biotech stocks. Workers could only invest in a small selection of conservatively diversified funds, like those available to federal workers under the Thrift Savings Plan. A full 20 years before a worker retires, his personal account would automatically start to shift into ever-less-risky investments—from a larger percentage of high-quality stocks into a larger percentage of high-quality government bonds, for example, as each year passes—to protect him from market volatility as he approaches retirement.

These sophisticated financial instruments—called “life-cycle funds”—tailored at low cost to fit the needs of masses of middle-income workers, just weren’t available 30 years ago. But they are now, and it’s foolish not to take advantage of advances in information and financial technology to ease our collective Social Security burden without forcing undue risk onto individual workers and retirees. And as columnist John Tierney recently pointed out in the New York Times, one of the unheralded benefits of the beautifully engineered personal accounts within Chile’s version of Social Security is that the lowest-income workers have the same access to good mutual funds within the very successful program as do the highest-income workers.

Democrats—and many Republicans—are not meeting Bush halfway, despite his willingness to preserve Social Security as a universal social program. Bush would retain its enduring principle: all workers pay in, and all retirees draw benefits out. Progressive indexing would also protect and expand Social Security’s original mission: “By providing more generous benefits for low-income retirees, we’ll make this commitment,” Bush said in April. “If you work hard and pay into Social Security your entire life, you will not retire into poverty.” Critics charge that personal accounts combined with progressive price indexing will “kill Social Security”—because, if all goes as planned, future middle-income and affluent retirees won’t get much of a traditional Social Security benefit. Most of their returns will come from their personal accounts.

In fact, this neat evolution does the opposite of killing Social Security. Social Security as it now exists is an unfunded Ponzi scheme that, as fewer workers must support growing numbers of retirees, and as each generation’s collective retirement benefits grow with real wage growth, is unsustainable. Polls have consistently shown that Americans worry, understandably, that Social Security won’t be there when they retire. In June, 51 percent of respondents to a New York Times/CBS poll said that they don’t think Social Security will be able to pay their future benefits—and 70 percent of Americans under 45 were doubtful that Social Security will be there when they retire. And middle-aged Americans, particularly those with defined-benefit corporate pension plans rather than personal 401(k) accounts, have closely followed the recent news that United Airlines will flout its pension obligations to its longtime employees, as the steel industry did a few years back (and as the auto companies might do too).

Progressive indexing, even with modest personal accounts in the mix, would solve much of Social Security’s long-term solvency problem. The only other way that politicians could fund Social Security, without increasing general taxes sharply, would be to raise the payroll tax on earners drastically (as they have nearly two dozen times over 70 years, from an original 2 percent to today’s 12.4 percent) or to hike the $90,000 earnings cap for Social Security taxes drastically. But even Democrats know that an 18 percent Social Security tax would kill Social Security’s support among middle-income earners. And a severe hike or elimination of the payroll-contribution cap, as Democratic Representative Robert Wexler proposed in May, would destroy the concept of Social Security. Sure, eliminating the cap would be just as progressive as Bush’s progressive-indexation plan. But if high-income workers were forced to pay Social Security taxes on all of their income without receiving correspondingly higher benefits, their capped benefits would have almost no relationship to their higher contributions, which would be merely a confiscatory tax. Then Social Security would really be welfare—just for more people.

Reform-minded conservatives must keep engaging the Dems. The reformers still have plenty of room for compromise as a reform package goes through the legislative process. But one area where the reformers can’t give an inch is the creation of large personal accounts within Social Security. Bush has already made their job more difficult, by indicating that he would sign legislation calling for an initial cap on personal accounts of just $1,000 a year for high-income workers, rather than allowing them to invest a full third of their payroll taxes in personal accounts. That would allow such workers to accumulate only $100,000 in their personal accounts at the end of their working lives—a little less than a third of what they would have under a full contribution. Such a modest account would not be a fair deal for these workers; their tiny personal accounts could not make up for the growth that would be lost through progressive indexing. Reformers must ensure that top earners can contribute at, or near, the full one-third of their payroll taxes. A gradual transition to personal accounts is fine, but reformers must ensure that the change is not so gradual that upper-middle-income workers don’t have a chance to accumulate substantial assets within Social Security in their lifetimes. In June, 45 percent of Americans polled told the same New York Times/CBS poll that they liked the idea of owning their own Social Security accounts, although many were worried about investing that money in the stock market, probably because reformers haven’t made their case for carefully regulated investments to the public. Further, half of those who said they were against personal accounts changed their minds when they were told they could leave assets in those accounts to their children.

Reformers have powerful arguments to make to middle-income Americans to build on this support. Americans are already worried about the fate of their own pensions and skeptical that they will ever see any return from their payroll taxes. Reformers should address those fears, pointing out that under today’s Social Security system, workers are investing in nothing more than futures contracts on politicians—that is, in the ability and willingness of future politicians to keep today’s promises. It wouldn’t be long before workers began to realize that the safest pension is the one each holds in his own personal account, not the one promised by a corporation or by the government.