Today’s reform will be tomorrow’s problem, goes an old political science axiom. Consider how the Interstate Commerce Commission, created in 1887 to end monopoly abuses by railroads on their branch lines, evolved within a few decades into a railroad cartel. Not until 1980 was the ICC stripped of its power to set rates, allowing transportation companies to begin competing again.

The corporate income tax has a similar history. It started as an innovative way to make the rich “pay their fair share.” But the interplay between the corporate income tax and the personal one over the last century has been the main driver of American tax complexity, transforming our tax code into a legal Jabba the Hutt; it had swollen to 73,954 pages as of 2013. Worse, the corporate income tax has had no end of perverse effects on the American economy—reducing wages, raising prices, lowering stock values, forcing manufacturing overseas, encouraging political corruption, and much more. It’s time to abolish it.

Like all wars, the Civil War was horrendously expensive. The federal government piled on taxes, including the country’s first personal income tax, to help pay for it. At war’s end, federal outlays fell sharply, declining 72 percent by 1867, and many war taxes were repealed—including, by 1872, the income tax. The main remaining sources of federal revenue were the tariff—which remained high to protect manufacturers from foreign competition—and excise taxes on commodities such as tobacco and liquor. Together, these levies generated more than 90 percent of federal revenues.

Both the tariff and excise taxes are consumption taxes and, as such, are inescapably regressive. The poor, by definition, must consume most of their income while the affluent can save much of theirs, escaping consumption taxes on it. Political pressure mounted to bring back an income tax to make the federal tax system more equitable.

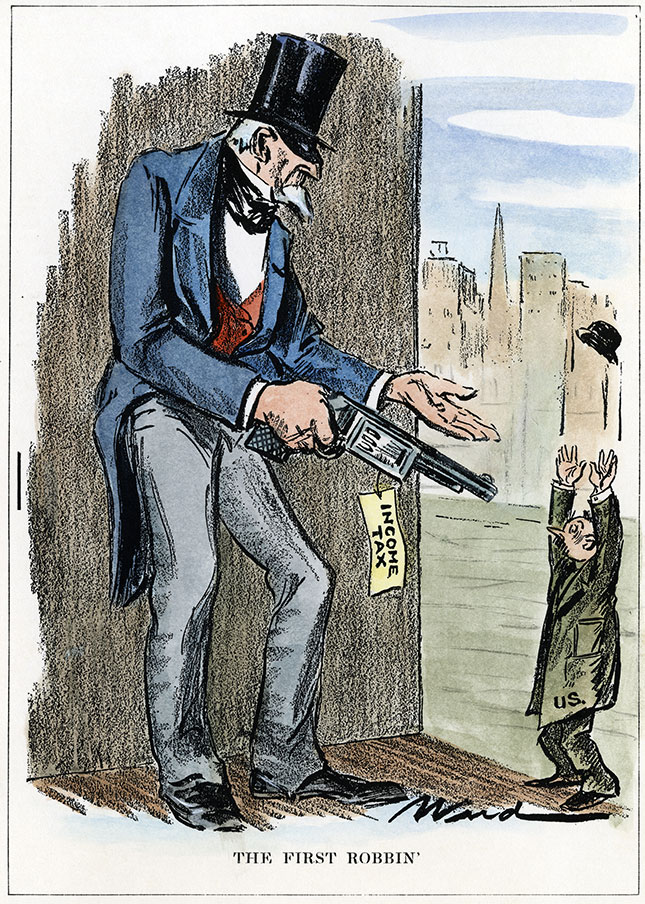

In 1894, with Democrat Grover Cleveland in the White House and Democratic majorities in both houses of Congress, an income tax made it into law. It differed sharply from the Civil War tax, which had exempted only the poor. Instead, it was aimed exclusively at the affluent, imposing a 2 percent tax on incomes over $4,000 of persons as well as corporations. Only about 85,000 households in the United States—less than 1 percent of the total—enjoyed incomes that high.

Unsurprisingly, the tax was immediately challenged. Charles Pollock, who owned ten shares of Farmers’ Loan & Trust in New York, sued to prevent the bank from paying the tax, which the bank did not want to do, anyway. It was a contrived case: Pollock, a man of ordinary means, assembled a legal team headed by Joseph H. Choate, perhaps Wall Street’s leading lawyer. (President William McKinley would appoint Choate ambassador to Great Britain four years later.) Contrived or not, the case received enormous press coverage, attracting far more public attention, for example, than Plessy v. Ferguson, the notorious 1896 Supreme Court decision that established the separate-but-equal doctrine in race relations.

The Pollock case made it to the Supreme Court in April 1895, with Justice Howell Jackson abstaining due to illness. The court considered three questions. Was a tax on the interest paid on state bonds a violation of state sovereignty? The Court ruled 8–0 that it was. Was a tax on the income from real property a direct tax—forbidden by the Constitution unless apportioned among the states according to population, something obviously impossible in this case? The Court ruled 6–2 that it was.

But when it came to the third question—Was a tax on corporate and personal income also a direct tax?—the court divided 4–4, resulting in that portion of the law being upheld. This was not a satisfactory outcome in so widely followed a case, so the court ordered a rehearing, and Justice Jackson, known to support the income tax, rose from his deathbed (he died three months later) to hear the case. Nearly everyone expected that the tax would be upheld 5–4, thanks to Jackson’s additional vote. But when the decision came down in May, it was 5–4 against. (It is generally believed, though not certain, that it was Justice George Shiras who switched his vote.)

But if the tax was dead, the political pressure to tax the incomes of the largely untaxed rich only grew. In 1909, advocates proposed that Congress simply pass again the 1894 tax bill—and, in effect, dare the Supreme Court, by then more liberal, to overturn it. This notion horrified the newly elected president, William Howard Taft, who revered the Court and would later serve as chief justice, an office he greatly preferred to the presidency. Taft felt that such a case would hurt the Court’s prestige and its position as the final arbiter of the Constitution.

“The incentive took hold to find ways to reduce the tax bite, and lawyers and tax accountants quickly began finding them.”

Taft, a gifted lawyer, devised a lawyerly alternative way to tax the incomes of the rich. He proposed an amendment to the Constitution that would overturn the Pollock decision by empowering the federal government to impose a personal income tax. Meantime, until the amendment could be ratified, he asked for a 2 percent income tax on corporations with incomes over $5,000. At the beginning of the twentieth century, corporate stock was, overwhelmingly, owned by the rich. So taxing corporate profits, it was thought, was, in a very real sense, taxing the rich.

To get around the Pollock decision, Taft argued that it was not a tax on income but rather an excise tax, measured in income, on the privilege of doing business as a corporation. The tax was lowered to 1 percent in conference and became law in August 1909. The Supreme Court later unanimously upheld it. Taft intended for his corporate tax to be only a temporary expedient. Once the Sixteenth Amendment establishing an income tax was ratified, as it was at the end of his term, he believed that the corporate tax would be abolished.

The Republicans were then the majority party, but Theodore Roosevelt’s third-party run in 1912 allowed the progressive Woodrow Wilson to win the White House and brought in an aggressively liberal Democratic Congress as well. It lost no time in writing an income-tax bill, which imposed a levy that started at 1 percent, with a personal deduction of $3,000 ($4,000 for married couples), and rose progressively after $20,000 of income, maxing out at 7 percent for incomes above $500,000—a Forbes 400 level at that time. There were other deductions, such as on dividend income up to $20,000.

But rather than abolish the corporate income tax, the new law raised it, eliminating the $5,000 deduction. Thus, the United States now had two separate income taxes, with no coordination between them. It still does.

The new taxes were, to be sure, very low. An upper-middle-class couple with a comfortable annual income of $5,000 would have owed just $10. With taxes this low, Americans had little incentive to avoid them.

That changed when the United States entered World War I. To finance the war, both income taxes were sharply raised. By the end of the war, the corporate rate stood at 35 percent, while the personal rate climbed to 77 percent. Rates fell considerably in the early 1920s, but rose again during Herbert Hoover’s administration, and even more under the New Deal policies of Franklin Roosevelt.

The incentive took hold to find ways to reduce the tax bite, and lawyers and tax accountants quickly began finding them, often by playing one income tax off against the other. Many wealthy people, for instance, simply incorporated their holdings so that they could mostly pay the lower corporate rate, paying the higher personal rate only on what they withdrew. In February 1933, shortly before his inauguration, Franklin Roosevelt was relaxing on board Vincent Astor’s palatial yacht off Florida. He was astonished to learn that many wealthy individuals had incorporated their yachts in order to pay the expenses of running them out of pretax income and deducting the cost of “renting” them as a business expense.

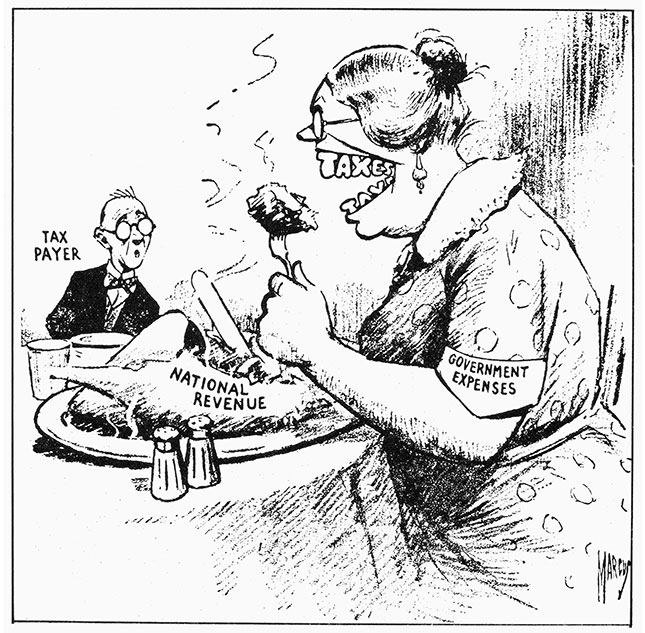

Businesses, seeking to compensate top employees with what amounted to tax-free income, elaborated the art of the expense account. Some even provided CEOs with luxury apartments as untaxed perks. The government’s need for revenue and everyone’s interest in paying as little as possible produced the political equivalent of what biologists call “coevolution”: as prey animals evolve to get better at avoiding predators, the predators evolve to get better at catching them. As accountants and lawyers found new ways to avoid income taxes, Congress tried to forbid these maneuvers, regulate them—or even encourage them. The tax code began to expand.

The original income-tax section of the tariff bill of 1913 ran a mere 13 pages. By 1942, the Revenue Act ran 208 pages, or 16 times as long. And of those 208 pages, 162—fully 78 percent of the text—dealt with closing or regulating the loopholes found in earlier revenue acts.

This expansion has continued ever since. Between 2001 and 2010, the tax code was amended no fewer than 4,130 times. Some amendments closed new loopholes, but others proved, in effect, to be new loopholes themselves. Many gave special treatment to just a few individuals or corporations. Thousands of lobbyists in Washington work solely on tax policy. In other words, the tax code’s byzantine complexity helps not only the rich and influential but also the members of Congress themselves, who can trade favorable tax treatment for campaign contributions. After all, if the best place to hide a book is in a library, the best place to hide a tax fiddle is in a tax code consisting of 74,000 pages of numbing prose.

Who pays the corporate income tax? Not the corporations—they’re just pieces of paper. The corporation writes the check, yes, but only people can actually pay taxes. As originally intended, the stockholders pay part of it because the tax makes the corporations less profitable, so their stock prices (and possibly dividends) are lower. But the workers also pay, receiving lower wages than they otherwise would, while customers pay higher prices. The exact ratio varies with each corporation’s competitive situation, but the Adam Smith Institute’s Ben Southwood calculates that, on average, workers pay 57.6 percent of the corporate income tax through lower wages. So a tax that began under William Howard Taft to assess the incomes of the rich mostly hits the average person.

By 2017, the United States had the highest corporate income tax in the developed world. And America was the only nation that taxed corporations on their global earnings, once repatriated, not just their domestic ones, as other countries did. The Trump administration took major steps toward reform, lowering the tax from 35 percent to 21 percent and joining the rest of the world in taxing only domestic profits, allowing $2.5 trillion in corporate profits parked overseas to be repatriated at much lower rates. Still, as the corporate income tax has entirely lost its original reason for being, it should be abolished altogether.

Abolition would certainly be expensive in the short term. The corporate income tax in fiscal year 2019 yielded about $245 billion, or 7 percent of total federal revenues. But much of that money would be made up quickly. With no corporate income tax, there would be no reason to tax dividends and capital gains at lower rates than ordinary income. That change would not only raise revenue but also put an end to a perennial bit of liberal demagoguery. And with no corporate income tax, the engine of tax complexity would disappear (as would a very large section of the tax code).

Today, corporate managers are mostly concerned with after-tax profits, since that’s what the stock market cares about. But after-tax profit is an artifact of lobbying success in Washington. With no corporate tax, the managers would care about what are now considered pretax profits, an artifact of wealth creation—the very reason that corporations exist.

With no tax, corporate profits would rise substantially, leading to increased dividends (fully taxable) and greater investment. And with higher profits, stock prices would rise commensurately. (Trump’s corporate tax reform was a factor in the notable rise of the stock market, pre-Covid.) Rising stocks would unleash a considerable “wealth effect,” as people saw their 401(k)s and mutual funds fattening in value—boosting the economy.

With no corporate income tax, no reason would exist to distinguish between profit and nonprofit corporations. Nonprofits would not have to jump through hoops to qualify for that designation, and the IRS would have one less means of corruption available to it.

If the United States were to adopt the world’s lowest corporate tax rate—zero—foreign companies would flock to invest here to avoid taxes at home. This development would force other countries to lower or eliminate their own taxes, spreading the boom worldwide.

Eliminating the corporate income tax would also strike a powerful blow against crony capitalism. Most federal government favors to industries come in the form of tax abatements. And subsidies for politically fashionable but unprofitable technologies, such as wind and solar power, are also part of the ever-expanding corporate tax code. Without a corporate tax code, there can be no favorable tax treatment and no subsidies except direct ones, and these would be much easier to hold to account.

So fundamental a change in the American tax system would be extraordinarily challenging to enact, of course. All laws, however perverse, produce winners and losers and, over time, entrenched constituencies. And among the big winners created by the corporate income tax are the members of Congress themselves.

The American Left has a vested interest, too. It has always used “corporations” as an all-purpose villain. The Left would be loath to part with that target and would probably fight to save it, helped by often economically illiterate journalists.

The Biden administration will not pursue abolition of the corporate income tax—in fact, it’s proposing an increase, from 21 percent to 28 percent. But the task is achievable for a popular and determined future president, one who ran on the issue and who enjoyed solid majorities in both houses of Congress. The Trump administration, in its lone term, moved the ball in the right direction. The job remains to be completed.

Top Photo: Pgiam/iStock