In 1962, as tensions ran high between school districts and unions across the country, members of the National Education Association gathered in Denver for the organization’s 100th annual convention. Among the speakers was Arthur F. Corey, executive director of the California Teachers Association (CTA). “The strike as a weapon for teachers is inappropriate, unprofessional, illegal, outmoded, and ineffective,” Corey told the crowd. “You can’t go out on an illegal strike one day and expect to go back to your classroom and teach good citizenship the next.”

Fast-forward nearly 50 years to May 2011, when the CTA—now the single most powerful special interest in California—organized a “State of Emergency” week to agitate for higher taxes in one of the most overtaxed states in the nation. A CTA document suggested dozens of ways for teachers to protest, including following state legislators incessantly, attempting to close major transportation arteries, and boycotting companies, such as Microsoft, that backed education reform. The week’s centerpiece was an occupation of the state capitol by hundreds of teachers and student sympathizers from the Cal State University system, who clogged the building’s hallways and refused to leave. Police arrested nearly 100 demonstrators for trespassing, including then–CTA president David Sanchez. The protesting teachers had left their jobs behind, even though their students were undergoing important statewide tests that week. With the passage of 50 years, the CTA’s notions of “good citizenship” had vanished.

So had high-quality public education in California. Seen as a national leader in the classroom during the 1950s and 1960s, the country’s largest state is today a laggard, competing with the likes of Mississippi and Washington, D.C., at the bottom of national rankings. The Golden State’s education tailspin has been blamed on everything from class sizes to the property-tax restrictions enforced by Proposition 13 to an influx of Spanish-speaking students. But no portrait of the system’s downfall would be complete without a depiction of the CTA, a political behemoth that blocks meaningful education reform, protects failing and even criminal educators, and inflates teacher pay and benefits to unsustainable levels.

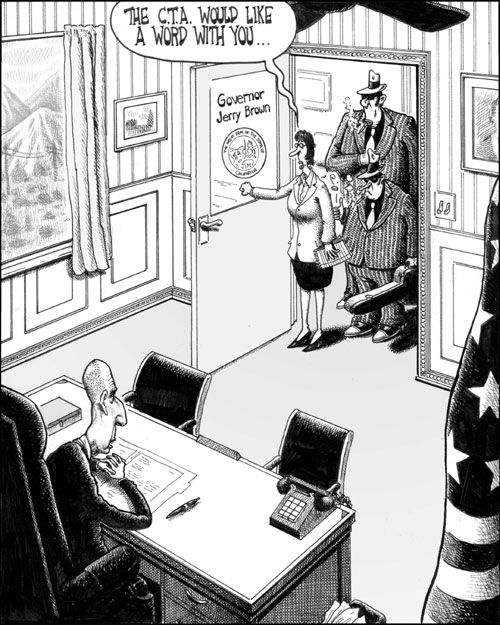

The CTA began its transformation in September 1975, when Governor Jerry Brown signed the Rodda Act, which allowed California teachers to bargain collectively. Within 18 months, 600 of the 1,000 local CTA chapters moved to collective bargaining. As the union’s power grew, its ranks nearly doubled, from 170,000 in the late 1970s to approximately 325,000 today. By following the union’s directions and voting in blocs in low-turnout school-board elections, teachers were able to handpick their own supervisors—a system that private-sector unionized workers would envy. Further, the organization that had once forsworn the strike began taking to the picket lines. Today, the CTA boasts that it has launched more than 170 strikes in the years since Rodda’s passage.

The CTA’s most important resource, however, isn’t a pool of workers ready to strike; it’s a fat bank account fed by mandatory dues that can run more than $1,000 per member. In 2009, the union’s income was more than $186 million, all of it tax-exempt. The CTA doesn’t need its members’ consent to spend this money on politicking, whether that’s making campaign contributions or running advocacy campaigns to obstruct reform. According to figures from the California Fair Political Practices Commission (a public institution) in 2010, the CTA had spent more than $210 million over the previous decade on political campaigning—more than any other donor in the state. In fact, the CTA outspent the pharmaceutical industry, the oil industry, and the tobacco industry combined.

All this money has helped the union rack up an imposing number of victories. The first major win came in 1988, with the passage of Proposition 98. That initiative compelled California to spend more than 40 percent of its annual budget on education in grades K–12 and community college. The spending quota eliminated schools’ incentive to get value out of every dollar: since funding was locked in, there was no need to make things run cost-effectively. Thanks to union influence on local school boards, much of the extra money—about $450 million a year—went straight into teachers’ salaries. Prop. 98’s malign effects weren’t limited to education, however: by essentially making public school funding an entitlement rather than a matter of discretionary spending, it hastened California’s erosion of fiscal discipline. In recent years, estimates of mandatory spending’s share of the state’s budget have run as high as 85 percent, making it highly difficult for the legislature to confront the severe budget crises of the past decade.

In 1991, the CTA took to the ramparts again to combat Proposition 174, a ballot initiative that would have made California a national leader in school choice by giving families universal access to school vouchers. When initiative supporters began circulating the petitions necessary to get it onto the ballot, some CTA members tried to intimidate petition signers physically. The union also encouraged people to sign the petition multiple times in order to throw the process into chaos. “There are some proposals so evil that they should never go before the voters,” explained D. A. Weber, the CTA’s president. One of the consultants who organized the petitions testified in a court declaration at the time that people with union ties had offered him $400,000 to refrain from distributing them. Another claimed that a CTA member had tried to run him off the road after a debate on school choice.

Weber and his followers weren’t successful in keeping the proposition off the ballot, but they did manage to delay it for two years, giving themselves time to organize a counteroffensive. They ran ads, recalls Ken Khachigian, the former White House speechwriter who headed the Yes on 174 campaign, “claiming that a witches’ coven would be eligible for the voucher funds and [could] set up a school of its own.” They threatened to field challengers against political candidates who supported school choice. They bullied members of the business community who contributed money to the pro-voucher effort. When In-N-Out Burger donated $25,000 to support Prop. 174, for instance, the CTA threatened to press schools to drop contracts with the company.

In 1993, Prop. 174 finally came to a statewide vote. The union had persuaded March Fong Eu, the CTA-endorsed secretary of state, to alter the proposition’s heading on the ballot from PARENTAL CHOICE to EDUCATION VOUCHERS—a change in wording that cost Prop. 174 ten points in the polls, according to Myron Lieberman in his book The Teacher Unions. The initiative, which had originally enjoyed 2–1 support among California voters, managed to garner only a little over 30 percent of the vote. Prop. 174’s backers had been outspent by a factor of eight, with the CTA alone dropping $12.5 million on the opposition campaign.

As the CTA’s power grew, it learned that it could extract policy concessions simply by employing its aggressive PR machine. In 1996, with the state’s budget in surplus, the CTA spent $1 million on an ad campaign touting the virtues of reduced class sizes in kindergarten through third grade. Feeling the heat from the campaign, Republican governor Pete Wilson signed a measure providing subsidies to schools with classes of 20 children or fewer. The program was a disaster: it failed to improve educational outcomes, and the need to hire many new teachers quickly, to handle all the smaller classes, reduced the quality of teachers throughout the state. The program cost California nearly $2 billion per year at its high-water mark, becoming the most expensive education-reform initiative in the state’s history. But it worked out well for the CTA, whose ranks and coffers were swelled by all those new teachers.

The union’s steady supply of cash allowed it to continue its quest for political dominance unabated. In 1998, it spent nearly $7 million to defeat Proposition 8—which would have used student performance as a criterion for teacher reviews and would have required educators to pass credentialing examinations in their disciplines—and more than $2 million in a failed attempt to block Proposition 227, which eliminated bilingual education in public schools. In 2002, the union spent $26 million to defeat Proposition 38, another school voucher proposal. And in 2005, with a special election called by Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger looming, the CTA came up with a colossal $58 million—even going so far as to mortgage its Sacramento headquarters—to defeat initiatives that would have capped the growth of state spending, made it easier to fire underperforming teachers, and ensured “paycheck protection,” which compels unions to get their members’ consent before using dues for political purposes. (A new paycheck-protection measure will appear on the November 2012 ballot.)

Cannily, the CTA also funds a wide array of liberal causes unrelated to education, with the goal of spreading around enough cash to prevent dissent from the Left. Among these causes: implementing a single-payer health-care system in California, blocking photo-identification requirements for voters, and limiting restraints on the government’s power of eminent domain. The CTA was the single biggest financial opponent of another Proposition 8, the controversial 2008 proposal to ban gay marriage, ponying up $1.3 million to fight an initiative that eventually won 52.2 percent of the vote. The union has also become the biggest donor to the California Democratic Party. From 2003 to 2012, the CTA spent nearly $102 million on political contributions; 0.08 percent of that money went to Republicans.

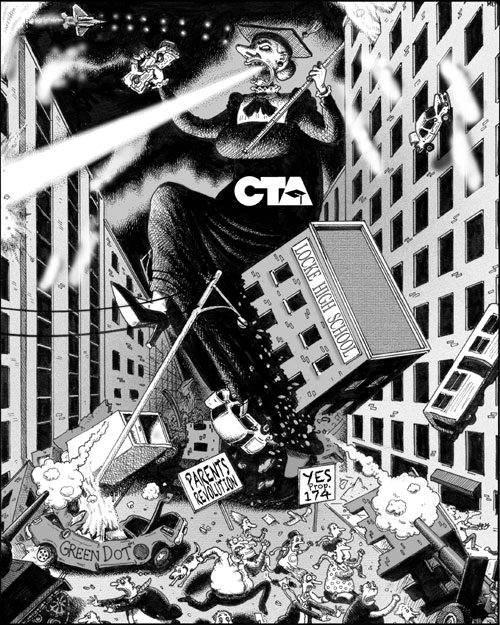

At the same time that the union was becoming the largest financial force in California politics, it was developing an equally powerful ground game, stifling reform efforts at the local level. Consider the case of Locke High School in the poverty-stricken Los Angeles neighborhood of Watts. Founded in response to the area’s 1967 riots, Locke was intended to provide a quality education to the neighborhood’s almost universally minority students. For years, it failed: in 2006, with a student body that was 65 percent Hispanic and 35 percent African-American, the school sent just 5 percent of its graduates to four-year colleges, and the dropout rate was nearly 51 percent.

Shortly before Locke reached this nadir, the school hired a reform-minded principal, Frank Wells, who was determined to revive the school’s fortunes. Just a few days after he arrived, a group of rival gangs got into a dust-up; Wells expelled 80 of the students involved. In the new atmosphere of discipline, Locke dropped “from first in the number of campus crime reports in LAUSD [Los Angeles Unified School District] to thirteenth,” writes Donna Foote in Relentless Pursuit: A Year in the Trenches with Teach for America. Test scores and college acceptance also began to rise, Foote reports.

But trouble arose with the union when Wells began requiring Locke teachers to present weekly lesson plans. The local CTA affiliate—United Teachers Los Angeles—filed a grievance against him and was soon urging his removal. The last straw was Wells’s effort to convert Locke into an independent charter school, where teachers would operate under severely restricted union contracts. In May 2007, the district removed Wells from his job. He was escorted from his office by three police officers and an associate superintendent of schools, all on the basis of union allegations that he had let teachers use classroom time to sign a petition to turn Locke into a charter. Wells called the allegations “a total fabrication,” and the signature gatherers backed him up. The LAUSD reassigned him to a district office, where he was paid $600 a day to sit in a cubicle and do nothing.

Luckily for Locke students, the union’s rearguard action came too late. In 2007, the Los Angeles Board of Education voted 5–2 to hand Locke High School to Green Dot, a charter school operator. Four years later, as the final class of Locke students who had attended the school prior to its transformation received their diplomas, the school’s graduation rate was 68 percent, and over 56 percent of Locke graduates were headed for higher education.

One of the most noticeable changes at Locke has ramifications statewide: when Green Dot took over, it required all teachers to reapply for their jobs. It hired back only about one-third of them. That approach is unimaginable in the rest of the state’s public schools, where a teaching job is essentially a lifetime sinecure. A tiny 0.03 percent of California teachers are dismissed after three or more years on the job. In the past decade, the LAUSD—home to 33,000 teachers—has dismissed only four. Even when teachers are fired, it’s seldom because of their classroom performance: a 2009 exposé by the Los Angeles Times found that only 20 percent of successful dismissals in the state had anything to do with teaching ability. Most terminations involved teachers behaving either obscenely or criminally. The National Council on Teacher Quality, a Washington-based education-reform organization, gave California a D-minus on its teacher-firing policies in its 2010 national report card.

Responsibility for this sorry situation goes largely to the CTA, which has won concessions that make firing a teacher so difficult that educators can usually keep their jobs for any offense that doesn’t cross into outright criminality. With the cost of the proceedings regularly running near half a million dollars, many districts choose to shuffle problem employees around rather than try to fire them.

Even outright offenses are no guarantee of removal, thanks to CTA influence. When a fired teacher appeals his case beyond the school board, it goes to the Commission on Professional Competence—two of whose three members are also teachers, one of them chosen by the educator whose case is being heard. The CTA has stacked this process as well by bargaining to require evidentiary standards equal to those used in civil-court procedures and coaching the teachers on the panels. One veteran school-district lawyer calls the appeals process “one of the most complicated civil legal matters anywhere.” As the Times noted, “The district wanted to fire a high school teacher who kept a stash of pornography, marijuana and vials with cocaine residue at school, but [the Commission on Professional Competence] balked, suggesting that firing was too harsh.” The commission was also the reason that, as the newspaper continued, the district was “unsuccessful in firing a male middle school teacher spotted lying on top of a female colleague in the metal shop”; the district had failed to “prove that the two were having sex.”

Another regulatory body dominated by CTA influence is the state’s Commission on Teacher Credentialing (CTC), the institution responsible for removing the credentials of misbehaving teachers. A report released in 2011 by California state auditor Elaine Howle found that the commission had a backlog of approximately 12,600 cases, with responses sometimes taking as long as three years. Because the CTC—which was created by an act sponsored by the CTA—is made up of members appointed by the governor, the CTA is able to bring its political pressure to bear on determining the commission’s makeup. In September 2011, for instance, one of Governor Jerry Brown’s appointments to the CTC was Kathy Harris, who had previously been a CTA lobbyist to the body.

The CTA’s most recent crusade for job security made clear that the union was prepared to jeopardize the financial future of California’s schools. Last June, it vigorously pushed (and Governor Brown hastily signed) Assembly Bill 114, which prevented any teacher layoffs or program cuts in the coming fiscal year and removed the requirement that school districts present balanced budget plans. The bill also forced public schools to prepare budget estimates that didn’t take into account the state’s downturn in revenues—meaning that schools could budget for activities even though there wasn’t money to pay for them. Since then, state officials have forecast that revenues for the 2012 fiscal year will be $3.2 billion lower than they were when the schools were making their budgets. Eventually, accommodations to reality will have to be made—at which time the CTA will, of course, use them to plead hardship.

Such pleas seem impudent coming from the highest-paid teachers in the nation, with an average annual salary of $68,000. For a bit of perspective, if two California teachers get married (not an unusual occurrence) and each makes the average salary, their combined annual income would be $136,000, nearly $80,000 more than what the state’s median household pulls down. That’s for an average annual workload of 180 days, only two-thirds of the average total in the private sector. Don’t forget retirement benefits: after 30 years, a California teacher may retire with a pension equal to about 75 percent of his working salary. That pension averages more than $51,000 a year—more than working teachers earn in more than half the states in the nation. And that’s just an average; from 2005 to 2011, the number of education employees pulling down more than $100,000 a year in pensions skyrocketed from 700 to 5,400.

With the state’s economy in tumult, however, prospects for the teachers’ retirement fund look grim. CalSTRS is now officially estimated to have about $56 billion in liabilities and about 30 years left before it runs dry, though many outside analysts think that those numbers are too optimistic. A report by the Legislative Analyst’s Office in November 2011 estimated that restoring full funding to CalSTRS would require finding an extra $3.9 billion a year for at least 30 years.

If California is to generate the economic growth necessary to mitigate its coming fiscal reckoning, it will need to retain its historical role as a leading site for innovation and entrepreneurship. But that won’t be possible if its next generation of would-be entrepreneurs attends one of the Golden State’s many mediocre or failing schools. And what little economic dynamism is left in California will be impeded if the union gets its way and the state increases its already weighty tax burden.

Meaningful change probably won’t come from elected officials, at least for now. The CTA’s size, financial resources, and influence with the state’s regnant Democratic Party are enough to kill most pieces of hostile legislation. For years, school reformers fantasized about a transformative figure who could shift the balance of power from the union through force of charisma and personality, taking his case directly to the people. Yet when that figure seemed to emerge in Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger, even he proved unable to alter the status quo, with his 2005 ballot initiatives to reform tenure, school financing, and political spending by unions all going down to decisive defeat. It’s unlikely that salvation will come from Governor Brown, either. The man who originally opened the door for the CTA’s collective bargaining has remained a steadfast ally of the union, firing four pro-reform members of the state board of education in his first few days in office and appointing a new group that included Patricia Ann Rucker, the CTA’s top lobbyist. Brown also avoided including any changes to CalSTRS in his October announcement of proposed pension reforms, probably because he had learned Schwarzenegger’s lesson that irking the CTA can lead to the demise of a broader agenda.

Parents, however, are starting to revolt against CTA orthodoxy. Unlike elected officials, parents—who want nothing more than a good education for their kids—are hard for the union to demonize. In early 2010, a Los Angeles–based nonprofit called Parent Revolution shocked California’s pundit class by getting the state legislature to pass the nation’s first “parent trigger” law, which lets parents at failing schools force districts to undertake certain reforms, including converting schools into independent charters. The law caps the number of schools eligible for reform at 75, but if early results are successful, it will become hard for Californians to avoid comparing thriving charter schools with failing traditional ones.

The CTA is fighting back, of course. In 2010, when 61 percent of parents at McKinley Elementary School in the blighted L.A. neighborhood of Compton opted to pull the trigger, the CTA claimed that “parents were never given the full picture . . . [or] informed of the great progress already being made”—despite the fact that McKinley’s performance was ranked beneath nearly all other inner-city schools in the state. Several Hispanic parents in the district also said that members of the union had threatened to report them to immigration authorities if they signed the petition. Eventually, the Compton Unified school board—heavily lobbied by the CTA—dismissed the petition signatures, with no discussion, as “insufficient” on a handful of technicalities, such as missing dates and typos. Though the union’s power had proved too much for the McKinley parents, an enterprising charter school operator opened two new campuses in the neighborhood anyway.

Institutions like Locke High School, Green Dot, Parent Revolution, and the Compton charters are glimmers of hope for California’s public school system. Despite their inferior resources, they have fought the CTA not by participating in direct political conflict but by undermining the union’s moral standing. These organizations reframe the education question in starkly humanitarian terms: In the California public school system, are anyone’s interests more important than the students’? It was a question that the CTA itself might have asked back when teachers entered the classroom to “teach good citizenship.”