The most gifted illustrator of his time has become as obsolete as the linotype machine and the rotogravure. Scholars remember Winsor McCay, of course. So do collectors: one of his full-color drawings recently went for six figures, and even his black-and-white panels are priced upward of $40,000. But the general public has lost touch with this giant of popular art. A reunion is long overdue.

McCay’s origins are wrapped in mystery. He claimed to have been born in Michigan in 1871, yet his gravestone puts his year of birth at 1869, while census data say the year was 1867—in Canada. One thing is certain: he grew up in a Detroit suburb. His teachers proclaimed him an artistic wunderkind, but his father, a real-estate agent, wanted him to be an entrepreneur, and with good reason. In a luminous coffee-table biography, New York University professor John Canemaker notes that Winsor had a younger brother, Arthur, who suffered from such severe mental illness that he had to be institutionalized. McCay senior knew that his sick son would need increasing attention and money, and he wanted his healthy son to earn his own keep as early as possible. Winsor defied his father by dropping out of business school, but, writes Canemaker, he “no doubt saw much of his brother in himself, and he feared and hated the horrible possibility that he would suffer Arthur’s unfortunate fate . . . so he kept on drawing for escape, for survival, and for salvation.”

At first, McCay supported himself by sketching quick portraits at Wonderland, a nearby amusement park. During the same period, an instructor taught him the elements of perspective and color theory. That knowledge paid dividends in Chicago, where he found work painting circus ads and posters. When better opportunities beckoned in Cincinnati, he moved there, doing chalk talks in local arenas—sketching people, places, and things as he chatted away—and drawing comic strips for the Cincinnati Enquirer.

McCay married in 1891 and, over the next seven years, gained a son, a daughter, and a mounting pile of bills. In dire need of extra income, he began to freelance for Life, then a humor magazine. Those early drawings announced the arrival of a major talent. One anti-imperialist pen-and-ink sketch showed Uncle Sam throwing dartlike American soldiers at a Filipino target. Another drawing presented a six-part cowboys-and-Indians episode that anticipated wide-screen Westerns by 60 years. No other commercial artist could approach McCay’s finely detailed lines and mordant wit.

The McCay name soon generated buzz in New York City, the epicenter of big-time journalism. Late in 1903, the New York Herald proffered a position as editorial cartoonist at a modest increase in salary. When Winsor hesitated, the paper volunteered to move the McCay family from Cincinnati to Gotham, gratis. McCay changed jobs. Within a few years, he changed some other things as well, among them the history of comic strips, newspaper illustration, and animated movies.

McCay began his Herald career with caricatures of officeholders. One typical panel featured 23 politicians reading or palavering, each one a remarkable likeness. But the artist was just marking time, waiting for the chance to create his own comic strip. Back then, newspaper comics were not a back-section afterthought; they were the main attraction. Ever since the invention of the four-color press in the mid-1890s, publishers had been booming their “Sunday funnies.” William Randolph Hearst’s New York Journal was typical. Its readers were promised “eight pages of iridescent polychromous effulgence that makes the rainbow look like a piece of lead pipe.”

Hearst wanted the newcomer to play on his team, but McCay was content to stay at the Herald, trying out new ideas on a weekly basis. His first comics failed to catch on. Then, in 1904, the artist hit pay dirt with Little Sammy Sneeze. Every Sunday, a boy tried and failed to suppress his sneeze, which was powerful enough to topple skyscrapers, destroy circuses, and crack the panels of the comic strip itself. Sammy was a one-joke affair, but Herald readers delighted in the familiar. Every weekend, they laughed uproariously, right on cue.

Late that year, McCay abandoned Sammy for Dream of the Rarebit Fiend. In this strip, various people found themselves in bizarre situations: a dentist climbed inside a patient’s mouth to check out a molar; a baby’s blocks fell and brought a city down with them; a stroller ran into 14 distorted images of himself, like those in a funhouse mirror. Then, in the last panel, the protagonist awoke and commented on his wild dream. McCay rendered every scene brilliantly—and, as the drawings show, with few erasures. Apparently, he saw everything in his mind ahead of time.

These Sunday funnies might have struck readers simply as vaudeville farce in cartoon form, complete with harrumphing businessmen, tyrannical mothers-in-law, imperious physicians, demanding wives, and meek clergymen. In fact, McCay was using the strip as a kind of exorcism. Dream of the Rarebit Fiend, observes Canemaker, often dealt with “delusions of persecution, hallucinations, irrationality, and insanity”—the very afflictions that had ravaged the cartoonist’s brother.

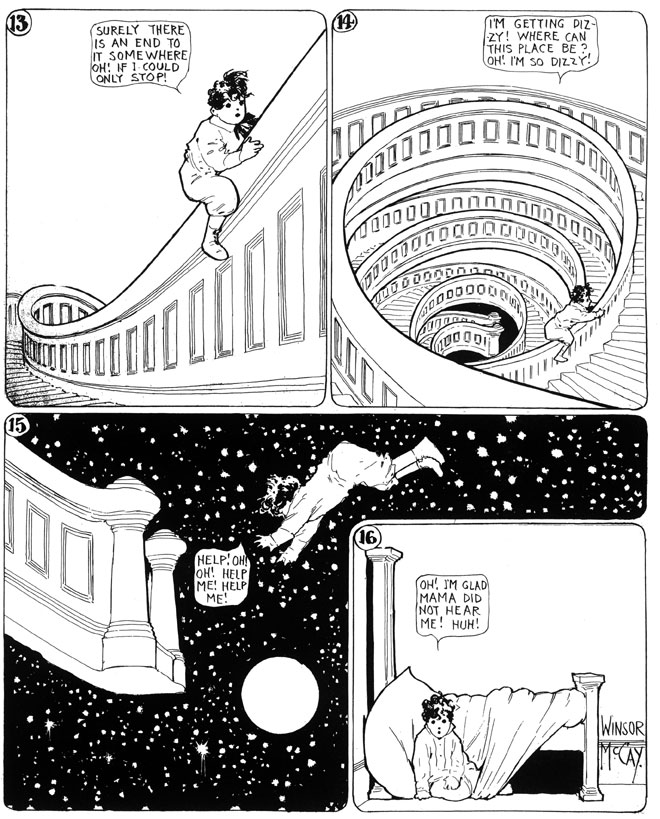

In 1905, Freud’s dream theories were the new, new thing—anatomized in professional journals, discussed in literary salons, and, inevitably, featured in magazines and newspapers. McCay had already ventured into dream territory, but in October he began a still more Freudian endeavor. No newspaper publisher, no comic-strip colleague, no reader had ever seen a full-color Sunday spread like Little Nemo in Slumberland. Unlike Rarebit, Nemo charted a complex and continuous story line. A fresh-faced boy, modeled on McCay’s seven-year-old son, Robert, bounds through an exotic and vibrant world. Two companions flank Little Nemo. Flip the Clown is based on a “rotund figure with a greenish cast to his face” whom the artist had seen smoking a cigar on a Brooklyn street. Accompanying Flip is Impie, a grass-skirted black child from the fictional Candy Islands.

In Slumberland, the rules of physics and logic are suspended. Inanimate objects take on lives of their own. Strange animals—a blue camel, a green dragon, a 100-foot-tall turkey—clamber over the ground or soar through the Milky Way. The ground opens up and swallows a pedestrian; free fall, one of humanity’s basic fears, is an ever-present threat. McCay insisted that he was only creating “well-drawn clean humor.” But something else was surfacing in his work. Nemo had tapped into his creator’s unconscious. The fact that McCay had surrounded him with visual comedy could not disguise the strip’s darker implications.

The episode of Queen Crystalette is typical. Nemo rises from his bed to get a glass of water and suddenly finds himself in a country whose citizens are made of glass. The little boy is taken to the queen, a lady so delicate she can barely return his bow. Nemo, says the narration, is “blind and deaf with infatuation.” He passionately embraces the regal figure and kisses her—whereupon she shatters like a tumbler dropped on stone, as does her retinue. Nemo, “heartsick and frightened,” wakes up with the “groans of the dying guardsmen still ringing in his ears.”

McCay’s fellow artists acknowledged Nemo as the most inventive and beautiful Sunday strip of the young century. General readers weren’t far behind. And in their wake came America’s most celebrated operetta composer, Victor Herbert, who turned Nemo into his next Broadway show. “The idea appeals to me tremendously,” he told a reporter. “It gives opportunities for fanciful incidents and for ‘color.’ It’s all in dreamland, you know, and that gives great scope for effects.” Herbert’s Little Nemo opened at the Victoria Theater on October 20, 1908, played for 15 weeks, and went on tour for two years.

By then, McCay had become something of a theatrical attraction himself, touring the vaudeville circuit as a chalk-talker. The highlight of his act was called “The Seven Ages of Man.” He began by drawing a pair of babies. For the next 20 minutes—a new picture every 30 seconds—McCay moved them in stages from infancy through childhood and adolescence to maturity and old age.

Dazzling as it was, “The Seven Ages” was merely a prelude to McCay’s next accomplishment. Movies were becoming America’s favorite form of entertainment, and he decided to achieve on film what he had done in the mind’s eye. He would have his characters go from place to place with articulated motion—make them walk and soar and emote as they only appeared to do in comics. There had been earlier attempts at animated shorts, but they were primitive, with herky-jerky figures drawn with little refinement or imagination. McCay sought to revolutionize animation. His assistant, John Fitzsimmons, recalled that he “timed everything with split-second watches. That’s how he got nice smooth action. For every second that was on the screen, McCay would draw sixteen pictures. . . . He had nothing to follow, he had to work everything out himself.”

Nemo was McCay’s first animated subject. Thousands of drawings brought the dreamer and his sidekicks to life. Shown in theaters, McCay’s ten-minute film puzzled as much as it enchanted. “It was pronounced very lifelike,” the artist recalled, “but my audience declared that it was not a drawing, but that the pictures were photographs of real children.” Fellow cartoonists knew better. One said that he had “witnessed the birth of a new art.”

Walt Disney would eventually take that art to another plane, but in 1910, Winsor McCay was the prime mover of American animation. Altogether, he produced, directed, and drew nine films, frame by frame. They ranged from Bug Vaudeville, featuring a butterfly corps de ballet, and Flip’s Circus, a centaurs’ pastoral, to the hand-colored How a Mosquito Operates. In the last, an immense, formally dressed insect named Steve lands on a drunk. He drills away, swelling larger with each new penetration. Soon too wobbly to get airborne and too voracious to survive, he explodes in a wash of blood.

If McCay’s self-proclaimed philosophy—“Mankind’s greatest disease is laziness”—was true, the artist was the healthiest man in New York. In addition to drawing comic strips and knocking about the vaudeville circuit, he announced plans for a new animated movie based on “the great monsters that used to inhabit the earth.”

Gertie the Dinosaur was one of the first instances of “anthropomorphic animation,” in which an animal was endowed with humanlike characteristics and personality. McCay, present at every showing, stood to the right of the screen. As he gestured, a diplodocus made its tentative entrance. Cracking his whip, ringmaster-style, McCay beckoned the long-necked creature to come all the way into the screen. Gertie walked with the ponderous steps of a great reptile, her legs fully articulated, her body suggesting bulk and authority. As the emcee put her through her paces, the animal occasionally tried to bite him. Each time, he ducked and then bawled her out; when he did, Gertie’s eyes brimmed with tears. Minutes later, her mood changed: she assumed comic attitudes, hurled a rock at a mastodon, sipped from a pond, and blithely executed some dance steps. As the pièce de résistance, McCay stepped offstage—and appeared a second later onscreen in an animated version of himself. He was borne away, bowing, in Gertie’s mouth. The film was a box-office sensation.

When Gertie was still in production, McCay had asked permission from the Herald’s editors to take the show to Europe. That would have meant a long absence, and they refused. He waited until his contract expired and jumped to Hearst’s American in 1911 at an enormous salary increase. With the extra money, he was able to maintain a grand home in Sheepshead Bay, along with several cars, one of them a top-of-the-line chauffeur-driven Packard. Few luxuries were out of his reach now. However, McCay’s new boss demanded more from his expensive hire than decorative Sunday pieces. After a settling-in period, McCay was named the American’s principal editorial cartoonist. Hearst assumed that this assignment would consume all the artist’s energy and time.

He was mistaken. True, Nemo would cease to dream, and there would be no more vaudeville performances, but the filmmaker would continue his work. In 1915, a German U-boat torpedoed a British luxury liner off the coast of Ireland. The notoriously Anglophobic Hearst ordered his papers to hold Britain responsible for the catastrophe. “Whether the Lusitania was armed or not,” explained an American editorial, “it was properly a spoil of war, subject to attack and destruction under the accepted rules of war.”

The Anglophilic McCay disagreed. In his view, Kaiser Wilhelm’s country was the guilty party and King George’s the injured one. Perhaps the Lusitania had been secretly carrying arms (later evidence revealed that the ship had explosives hidden aboard), but that was beside the point. Some 1,200 innocent civilians had died in the attack, among them 128 U.S. citizens. The chief was wrong, McCay decided.

In 1916, with two assistants, McCay began work on his most ambitious enterprise. For the first time, the animator used “cels”—celluloid sheets—to convey the action drawings; behind them was an immobile horizon. After nearly two years of work, The Sinking of the Lusitania appeared, widely promoted as “The Only Record of the Crime That Shocked Humanity!” Audiences were astounded by McCay’s ability to make them feel the vessel’s mid-ocean pitch and roll. In his film, the Lusitania sails on undisturbed—until the camera abruptly changes its point of view. Diving underwater, it shows fish getting out of the way as the German torpedo speeds toward its destination. Seconds later, a huge explosion ignites the sky. Hysterical passengers and intrepid officers crowd the screen. Lifeboats are thrown into the water and occupied, but only a few passengers can be rescued before the Lusitania lurches and goes under. Many prominent personages are aboard, among them millionaire sportsman Alfred Vanderbilt and theatrical producer Charles Frohman. The showman’s last words provide a brief uplift: “Death is but a beautiful adventure of life.” Then all is grief and horror. At the finale, a young mother tries to raise her baby above the waves, hoping against hope. As the two drown, a title appears, expressing McCay’s outrage: “The man who fired the shot was decorated for it by the Kaiser!—And yet they tell us not to hate the Hun.”

The Sinking of the Lusitania was a national triumph. By 1918, America had entered the Great War, the original Nemo had become Sergeant Robert McCay of the 27th Army Division, and the public had ratified the animator’s personal views. It was the publisher who was out of step. Citizen Hearst retreated, printing little American flags on the American’s front page and acknowledging “popular sentiment in these troublous times.”

At the peak of his prowess and reputation, McCay left serious animation forever. Perhaps he felt he had nothing more to prove; perhaps the labor-intensive work had exhausted him. And he abandoned the comics page, too, vanishing into editorial work for the rest of his career.

McCay’s immediate boss was Arthur Brisbane, grandfather of the New York Times’s current public editor. Biographer W. A. Swanberg described the elder Brisbane as a “vest-pocket Hearst, . . . a madman for circulation, a liberal who had grown conservative, an investor.” The editor had a ham hand, though, and McCay’s colleagues didn’t expect the artist to remain long in his position. After all, McCay was well-to-do and could have walked away to an early and luxurious retirement.

Instead, he settled in at the American, content to follow instructions from on high. In one typical drawing, an isolationist Uncle Sam sits out “Old World Political Storms”; in another, a dig at society’s “freeloaders,” a hog and a human being nap on a lawn. The caption reads: “You Can Forgive the Pig—Not the Man.” Clearly, these were made-to-order cartoons.

But the truth was that McCay’s political and social opinions were often in lockstep with management’s. Now that the armistice was in effect, for example, he and Hearst agreed to give peace a chance. McCay drew the interior of a museum with a mastodon, a dinosaur, and a torturer’s rack. A figure marked WAR looms in the doorway. A museum guide welcomes him: “Oblivion’s Cave, Step Right In.” In another cartoon, a monstrous Tammany tiger stalks outside the White House under the disapproving gaze of Thomas Jefferson’s ghost. One of McCay’s last cartoons depicts a figure named DOPE who peddles his merchandise to an eager throng, unaware that they have three destinations: the penitentiary, the cemetery, and the madhouse.

At the time of McCay’s fatal stroke in 1934, he looked roughly a decade older than his actual age, which was somewhere in his mid-sixties. Unwilling and perhaps unable to stop for rest, he had burned himself out. By then, the worlds of cinema and Sunday comics had changed beyond recognition. Mickey Mouse was an established star, Donald Duck quacked in the wings, and the development of Snow White was under way. In the comics, the popularity of Flash Gordon and Mandrake the Magician indicated a new appetite for superheroes, which Batman, Superman, and Captain Marvel would soon satisfy. Intricate, whimsical fantasy no longer satisfied the public taste.

For more than three decades, McCay and his oeuvre fell into obscurity. Then, in 1968, a mini-revival began. The Musée des Arts Décoratifs at the Louvre exhibited some panels from Little Nemo, Little Sammy Sneeze, and other McCay creations. The artist was hailed in a history of comics as “the greatest innovator of the age,” someone who deserved a place “within the great intellectual and aesthetic current leading from Breughel to the surrealists.” Nine years later, the Whitney Museum in New York ran Gertie and other McCay films. Academy Award–winning animator Chuck Jones remarked: “The two most important people in animation are Winsor McCay and Walt Disney, and I’m not sure which should go first.”

Comic-strip artists belatedly acknowledged their forerunner. Milton Caniff of Terry and the Pirates remembered a childhood spent studying the vibrant line, layout, and color in Little Nemo. He found the draftsmanship incomparable and expressed profound gratitude “for the education McCay gave a kid in the boondocks—without ever knowing the kid was enrolled in his class.” Illustrator Burne Ho- garth, founder of the School of Visual Arts, thought that McCay stood “very high with the great figures of this 20th century art form. . . . There is no credible figure today who can match this kind of output and intense artistic zeal.” Maurice Sendak, the doyen of children’s books, assayed Little Nemo and found it “nearly all pure gold.” Its creator was “one of America’s rare, great fantasists.” (Sendak’s In the Night Kitchen is a self-proclaimed homage to McCay.)

Today, Amazon.com offers a small choice of reprints of the strips, among them paperback selections from Little Nemo in the Palace of Ice and Rarebit Fiend, as well as a hardcover edition of Canemaker’s biography. But no major gallery has mounted a true retrospective of an American master, whose vivid and fantastic productions, unlike the pop art pieces that aped them, were the real thing.