When hedge-fund manager John Paulson donated $8.5 million last year to Success Academy, a public charter school network in New York City, he acted in a long tradition of America’s wealthiest citizens financing educational opportunities for the less fortunate. Today, this philanthropy brings to mind names like Bill Gates, Sam Walton, and Eli Broad. A century ago, it included Andrew Carnegie, John D. Rockefeller, J. Pierpont Morgan, George Eastman, and John Wanamaker.

Then, as now, an overriding goal of these benefactors was to improve the social condition of the poor in general, and the black poor in particular. Then, as now, detractors accused wealthy givers of ulterior motives—of advocating the “wrong kind” of education or of donating out of a desire to undermine democratic governance, secure wealth, and burnish their image. What’s not in dispute, however, is that the traditional public schools continue to do an abysmal job of educating low-income minorities, and thus demand remains acute for educational philanthropy that offers alternatives for the underprivileged.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

Paulson didn’t pick Success Academy out of a hat, of course. The charter network is based in New York City, where two out of three students perform below grade level and one in four schools fails 90 percent of its charges. Blacks and Hispanics, who constitute 67 percent of the system’s students, are faring worst. In 2014, 29 percent of New York City public school students passed the state reading exam, and 35 percent passed the math exam. But just 18.5 percent of black students and 23.2 percent of Hispanic students in the Big Apple were proficient in math, and only 19 percent of black and Hispanic test-takers passed the reading portion.

By contrast, Success Academy, which, like other charters, operates free of the bureaucracies and union work rules that govern traditional public schools, has enrolled the same disadvantaged kids from the same neighborhoods with the same pathologies, yet produced dramatically better results. “Though it serves primarily poor, mostly black and Hispanic students,” reported the New York Times, “Success is a testing dynamo, outscoring schools in many wealthy suburbs, let alone their urban counterparts.” In 2015, 11,000 students—all chosen by lottery—were attending 34 Success Academy schools in New York City. Some 93 percent passed the state math test, beating even the 75 percent pass rate for Scarsdale, an upscale suburb where median family incomes are just under $241,000 and the poverty rate is 2.1 percent. On the reading test, 68 percent of Success students passed, compared with 64 percent for Scarsdale.

The New York Post has declared Success Academy the top public school system in the Empire State, and it’s hard to argue otherwise. In 2015, Success students scored in the top 1 percent in math and the top 3 percent in reading among all schools in the state. At 72 percent, the math exam passing rate among Success students with disabilities was more than double the city’s passing rate among students without disabilities. Success schools also have made huge strides toward closing the racial-achievement gap. Nationwide, black students on average perform two grade levels behind their white peers. That’s not the case at the Success Academy, where black students outperformed New York City white students by 35 points in math and by 14 points in reading. Is it any wonder that the charter network had more than 22,000 families enter the lottery for only 2,300 open seats in 2014? Is it any wonder that John Paulson was so eager to help Success Academy expand? Like his philanthropic predecessors, he prioritizes improving black outcomes, not preserving a public education framework that continues to ill-serve poor minorities.

The Founders viewed education as crucial to self-government. A plaque outside Federal Hall in lower Manhattan commemorates Congress’s passage of the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, which stipulated that “Religion, morality and knowledge being necessary to good government and the happiness of mankind, schools and the means of education shall forever be encouraged.” Though most states in the antebellum South passed legislation making it a crime to teach enslaved children how to read or write, thousands learned anyway. The value of an education was not lost on blacks, who took great risks to become literate.

Frederick Law Olmsted, who chronicled his tours of the slave South, wrote, for example, about the public whipping of a free black man in Washington, D.C., after officials discovered him running a secret school for slaves. Thomas H. Jones—enslaved in North Carolina for 45 years before escaping and becoming an abolitionist—recounted his furtive efforts to educate himself while working as a clerk in his master’s store. Jones’s master arrived earlier than usual one morning, as Jones, who had only recently learned to write his name, was in the stockroom studying his new spelling book. Hearing his master coming, Jones tossed the book behind some barrels. His master saw the movement, though, and accused Jones of stealing. “Without a moment’s hesitation, I determined to save my precious book and my future opportunities to learn out of it,” writes Jones. “I knew if my book was discovered that all was lost, and I felt prepared for any hazard or suffering rather than give up my book and my hopes of improvement.” Jones immediately had his resolve tested. “He charged me again with stealing and throwing something away, and I again denied the charge,” writes Jones. “In a great rage, he got down his long, heavy cow-hide and ordered me to strip off my jacket and shirt, saying with an oath, ‘I will make you tell me what it was you had when I came.’ . . . He cut me on my naked back, perhaps thirty times, with great severity, making the blood flow freely.” Jones endured a second whipping—“with greater severity and at greater length than before”—and then a third before his master finally gave up. “I was determined to die, if I could possibly bear the pain, rather than give up my dear book,” he writes. “This was my best, my constant friend. With great eagerness I snatched every moment I could get, morning, noon and night, for study. I had begun to read; and oh, how I loved to study, and to dwell on the thoughts which I gained from reading.”

Though educating blacks was not forbidden in the antebellum North, not all black Northerners had access to public schools. Racially mixed schools were uncommon, even above the Mason-Dixon Line, and many black schools lacked white support and struggled financially. Nevertheless, the 1850 census showed that more than half of the 500,000 free blacks and about 5 percent of the 4 million slaves in the U.S. could read and write. “[B]efore northern benevolent societies entered the South in 1862, before President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, and before Congress created the Bureau of Refugees, Freedom and Abandoned Lands (Freedmen’s Bureau) in 1865, slaves and free persons of color had already begun to make plans for the systematic instruction of their illiterates,” notes historian James Anderson, a professor of the history of education at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Within two generations of emancipation, a majority of blacks would be literate—“an accomplishment seldom witnessed in human history,” observes economic historian Robert Higgs.

After the Civil War, Southern Republicans undertook a kind of nation-building in the region, where “slavery had sharply curtailed the scope of public authority,” writes Eric Foner in his history of Reconstruction. Before the war, blacks had been under the authority of their owners, not the government. “With planters enjoying a disproportionate share of political power, taxes and social welfare expenditures remained low and southern education, as one Democrat admitted after the war, was a ‘disgrace.’ ” In some places, public schools, hospitals, and penitentiaries were nonexistent and had to be established. Pre-Reconstruction, Tennessee was the only Southern state with a tax-supported school system. Even when these institutions did exist, they typically were underfunded and in no position to handle the greatly expanded citizenry.

Officials at the Freedmen’s Bureau, set up by the federal government to assist former slaves, “viewed schooling as the foundation of a new, egalitarian social order,” writes Foner. But “no state could meet entirely the enormous costs of building a school system virtually from scratch, and traditions of local autonomy and low taxation valued by native whites, Republican as well as Democrat, limited the authority of state education officials.” As late as 1900, Kentucky was the lone Southern state with compulsory school-attendance laws, which were already the norm in the North.

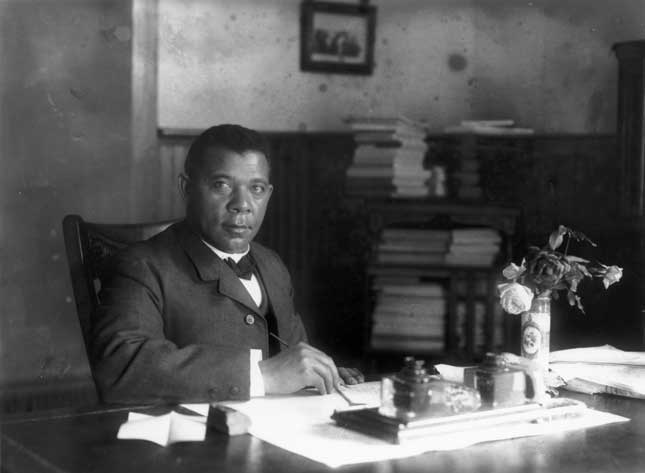

By all accounts, blacks left bondage eager to learn. “They rushed not to the grog-shop but to the schoolroom,” wrote Harriet Beecher Stowe. “They cried for the spelling-book as bread, and pleaded for teachers as a necessity of life.” Booker T. Washington, the educator and former slave, wrote that “few people who were not right in the midst of the scenes can form any exact idea of the intense desire which the people of my race showed for an education.” Progress was made, but the pace was fitful. By 1875, for example, about half of both black and white children in Florida, Mississippi, and South Carolina were attending classes, but more than 70 percent of the black population remained illiterate. And even these black gains would be jeopardized as Reconstruction wound down in 1877, federal troops withdrew, Southern states passed Jim Crow laws, and white supremacy reasserted itself.

Leading philanthropists intervened on behalf of blacks. In 1880, Georgia was home to the nation’s largest black population, yet had no institutions of higher learning for black women. The next year, two teachers from Massachusetts, Sophia Packard and Harriet Giles, founded the Atlanta Baptist Female Seminary for freed slaves. In 1882, Packard and Giles recruited John D. Rockefeller as the school’s major donor. “Inspired by these women, Rockefeller, though socially conservative, became unalterably committed to black education,” writes Rockefeller biographer Ron Chernow. The school was renamed in honor of Rockefeller’s wife, Laura Spelman, and her family of staunch abolitionists. Today, Spelman College is one of the premier historically black institutions of higher learning in America. Morehouse College, another highly regarded black school, is located on land donated by Rockefeller and named after Henry Morehouse, an official at the Home Mission Society in the 1880s who helped channel Northern philanthropy to black schools in the South.

Writes Chernow: “As one chronicler of Rockefeller philanthropy has noted, ‘The Rockefeller files are more extensive on this subject of the welfare of the Negro race than on almost any other.’ ” Indeed, Chernow continues, “the black women’s college in Atlanta became a Rockefeller family affair, as John was joined in his interest by his Spelman wife, sister-in-law, and mother-in-law. When it came to black education and welfare, Rockefeller displayed unwonted ardor.” Nor was Rockefeller’s interest in black learning limited to Georgia or to higher education. In 1902, he and his son, John D. Rockefeller, Jr., put up $1 million to create the General Education Board, dedicated to promoting “education within the United States without distinction of race, sex or creed.” Initially focused on creating high schools and promoting educational standards for Southern blacks, the GEB would become the world’s foremost educational philanthropy.

“Once Reconstruction was over, you had a more or less endemic situation where public funding for schools went disproportionately to white public schools and black public schools became starved for financial support,” according to historian Mary Hoffschwelle, who teaches at Middle Tennessee State University. “By the end of the nineteenth century, you had essentially a very stunted development of black public education in Southern states. In many communities, it was limited to elementary grades. Only in towns and cities were there a few examples of secondary schools, and public collegiate education was limited as well.”

At the end of the nineteenth century, the nation’s preeminent black educator was Booker T. Washington, a star graduate of Virginia’s Hampton Institute, the teacher-training school for blacks that Congregationalist missionaries had established in 1868 on a site where runaway slaves sought refuge during the Civil War. When Washington was at Hampton (where he also taught) in the 1870s, resources weren’t the only problem that black schools faced, as an 1875 New York Times story, cited by Washington biographer Robert Norrell, made clear. “In the 10 years since the end of the war, hundreds of new black schools had been burned across the South, dozens of teachers terrorized and killed,” recounts Norrell. “One of Booker’s classmates, the reporter wrote, had escaped the Ku Klux Klan only by hiding, and his two fellow teachers had been murdered.”

Washington moved to Alabama in 1881 to serve as the first president of what became the Tuskegee Institute, a school modeled on Hampton. He and the Hampton-Tuskegee approach to black education drew prominent critics. “You scratch one of these colored graduates under the skin and you will find the savage,” said Senator Ben Tillman of South Carolina. “Booker T. Washington simply equips the negro for more deadly competition with the white man; a hundred more colleges like his would only arouse more race antagonism.” Georgia governor Allen Candler publicly denounced higher education for “the darky” and Northern efforts to finance it. “Do you know that you can stand on the dome of the capitol of Georgia and see more negro colleges with endowments than you can white schools?” he complained.

Even some who shared Washington’s objectives disliked his methods. Black Northerners, such as the scholar W. E. B. Du Bois, preferred a liberal arts curriculum over Tuskegee’s emphasis on practical learning. But “there was a lot of both” going on, says Hoffschwelle. “At the grassroots level, you had both vocational and academic education advancing hand in hand.”

The philanthropists generally favored the Tuskegee approach. “A key factor in Washington’s rise to fame was the support of industrial philanthropists, who virtually developed Tuskegee Institute and played the central role of projecting Washington onto the national scene,” writes Anderson. “Through their influence Booker T. Washington and the Hampton-Tuskegee Idea were heavily advertised in national periodicals and magazines during the late nineteenth century.” Washington, adds Anderson, “knew full well that Tuskegee would quickly fall were it not for the philanthropists’ political and economic support.”

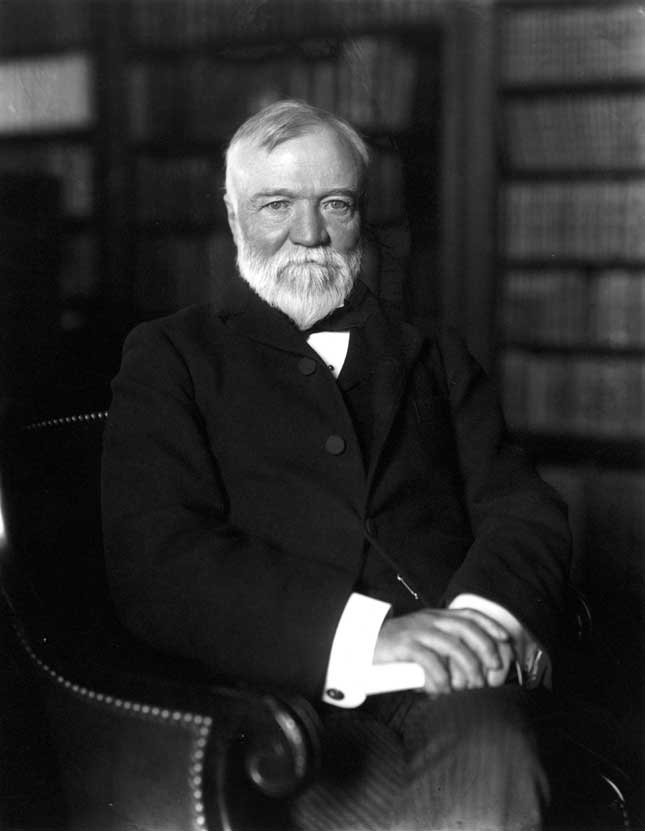

The school’s endowment-fund committee included department-store magnate Robert Ogden, investment banker George Peabody, and railroad executive William Baldwin. Tuskegee’s most significant donation, however, came courtesy of Andrew Carnegie, who gave the school $600,000 in U.S. Steel bonds in 1903. Washington’s autobiography, Up from Slavery, had caught Carnegie’s attention. The gift more than doubled Tuskegee’s endowment, and Carnegie came to trust Washington’s judgment. “Carnegie had huge confidence in him,” Norrell explains. “Carnegie got in his dotage”—he died in 1919, at age 83—“and people were coming to him all the time for money, and he would say, ‘Well, you have to go see Booker Washington.’ He wouldn’t give money to anyone in the South, black or white, without consulting Booker T. Washington.”

Washington also wanted more focus on the elementary schooling of blacks, so that they could better handle the work at places like Tuskegee. Once again, he looked northward to the moneyed class; this time, he found a willing midwesterner named Julius Rosenwald. The Chicago-based Rosenwald had made his fortune running Sears, Roebuck and Company, the nation’s then-largest retailer. A son of German immigrants, Rosenwald already was known for giving generously to local Jewish charities and the University of Chicago when he came across two books in the summer of 1910 that would have a major impact on his future philanthropy. The first: Washington’s best-selling Up from Slavery. The second was a biography of William Baldwin, the white New England businessman and Washington associate with a keen interest in helping black Southerners. “It is glorious, a story of a man who really led a life which is to my liking and whom I shall endeavor to imitate,” Rosenwald later wrote.

The next year, Rosenwald offered to donate $25,000 to Tuskegee. Washington asked if he could use a portion of the money to help build a handful of black elementary schools nearby. The first Rosenwald school was built in Loachapoka, Alabama, in 1913, to the delight of the local black community. “Pleased with this initial success, the Sears, Roebuck president gave money to help build 80 more schools,” writes Norman H. Finkelstein in Schools of Hope. The collaboration with Washington “was just the beginning of what would become Julius Rosenwald’s most important legacy. Over the next two decades, he would be responsible for helping to build more than 5,300 schools.”

The Rosenwald Rural Schools Initiative, as it came to be known, was a matching-grant program designed to narrow racial learning gaps in the South, where nearly 90 percent of black Americans then lived. Rosenwald put up a portion of the costs on the condition that the balance come from the local community in the form of cash and labor. The arrangement was consistent with Washington’s self-help philosophy and even garnered support from white communities, including white property owners, who sometimes donated land.

In 2011, a Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago study detailed the impact of this Washington-Rosenwald alliance. According to the authors, Daniel Aaronson and Bhashkar Mazumder, blacks born in the South between 1880 and 1910 completed three fewer years of schooling than whites. Both groups made gains over that period, but blacks experienced no relative progress. Yet for blacks born between World War I and World War II, the educational gains relative to those of whites were dramatic, thanks largely to the Rosenwald initiative. “In addition to making schooling more accessible, the program represented a sea change in the quality of schools,” the authors note. “The buildings were constructed based on modern designs that ensured adequate lighting, ventilation and sanitation. Classrooms were required to be fully equipped with books, chairs, desks, blackboards, and other materials to ensure an adequate learning environment.” Teachers also received better training and salaries.

“The Gilded Age philanthropists who helped educate black Southerners regularly found themselves excoriated by elites.”

These changes increased not only the quality of education but also the percentage of black children attending school. “Within a generation, the racial gap in the South declined to well under a year and was comparable in size to the racial gap in the North,” observe Aaronson and Mazumder. “Our main finding is that rural black students with access to Rosenwald schools completed over a full year more education than rural black students with no access to Rosenwald schools, a magnitude that, in the aggregate, explains close to 40 percent of the observed black-white convergence in educational attainment in the South for cohorts born between 1910 and 1925.” Those today who obsess over racial imbalances in our schools might consider that, even in the Jim Crow era, black children needed quality schools more than they needed white classmates.

Washington died in 1915, at 59, but Rosenwald and the Tuskegee Institute continued the school-building project for another three decades. By the time the Rosenwald Fund closed in 1948—in accordance with the wishes of its namesake, who died in 1932—more than one in three black children in the rural South had attended a Rosenwald school. In addition to constructing school buildings and training teachers who later would educate the likes of Congressman John Lewis and poet Maya Angelou, Rosenwald’s philanthropy supported the careers of a who’s who of black America in the first half of the twentieth century. Recipients of his largesse included the painter Jacob Lawrence; the photographer Gordon Parks; the poet Langston Hughes; the contralto Marian Anderson; the 1950 Nobel Peace Prize winner Ralph Bunche; and the noted authors James Baldwin, Zora Neale Hurston, and Ralph Ellison. The Rosenwald Fund financed one-third of the NAACP’s litigation costs in Brown v. Board of Education, the landmark Supreme Court ruling against state-sponsored segregation that would lead to the obsolescence of Rosenwald schools.

In Rosenwald, a documentary released last year, historian David Levering Lewis says that Julius Rosenwald and his education fund served as “a virtual Department of Education” for blacks. “Without that initiative, we would have a different America.” Julian Bond, the late civil rights leader and Martin Luther King, Jr. confidante, is also interviewed in the film. “You can look at the people who got grants from Julius Rosenwald and say these people are the predecessor generation to the civil rights generation that I’m a part of,” says Bond.

If the Gilded Age philanthropists who helped educate black Southerners after Reconstruction are viewed in a kinder light now, they regularly found themselves excoriated by political and intellectual elites in their day. Julius Rosenwald received criticism for building schools that accommodated legal segregation. Andrew Carnegie’s ulterior motive, said critics, was cheap labor for American industry. John D. Rockefeller’s charitable giving was dismissed as little more than an attempt to lighten his tax bill and soften his public image. “[T]he one thing that the world would gratefully accept from Mr. Rockefeller,” said Samuel Gompers, president of the American Federation of Labor, “would be the establishment of a great endowment of research and education to help other people see in time how they can keep from being like him.”

Today’s leading education philanthropists—Bill Gates, Eli Broad, the Walton family—encounter obstacles quite different from those of their predecessors. Thanks to the civil rights victories in the second half of the twentieth century, segregationists and apathetic government officials no longer stand in the way of a decent education for blacks. By the time sociologist James Coleman published his landmark study on educational opportunity in 1966, spending per pupil already was nearly identical in black and white schools. Since 1970, federal education spending has increased by an inflation-adjusted 375 percent, and the public school workforce has grown 11 times faster than enrollment. Harvard’s Paul Peterson notes that, since the 1960s, per-pupil spending has more than tripled after inflation, while the number of students per teacher has fallen by a third.

For education philanthropists, it’s not overall education expenditures but how that money gets spent that remains a major concern. The U.S. spends more than $600 billion annually on K–12 schooling. Many wealthy donors know that they can’t compete dollar-for-dollar with public spending and the special interests that protect the education status quo. The National Education Association, which represents public school teachers, is by far America’s largest union. Along with its sister organization, the American Federation of Teachers, and thousands of state and local affiliates, it is also the country’s most consequential labor group. The unions “influence schools from the bottom up, through collective bargaining activities that shape virtually every aspect of school organization,” writes Stanford University political scientist Terry Moe. “And they influence schools from the top down, through political activities that shape government policy.”

Given that annual philanthropic K–12 education largesse represents only about 1 percent of total education spending, Gates, Broad, Walton, and others would have no hope of counterbalancing this union influence anytime soon. But wealthy donors have found ways to make a difference at the margins. They have backed teacher-training programs like Teach for America, which, unlike the vast majority of graduate education programs, recruits the smartest students from the most selective colleges and then dispatches them to underperforming school districts. They have pushed for teacher evaluation systems that factor in student test scores and have supported efforts to reward instructors based on effectiveness rather than just seniority. Most important, they have facilitated more school choice for needy families via vouchers, tax-credit programs, education-savings accounts, and other means. Alternative models, from Catholic schools to nonsectarian private schools to public charters, have long shown that ghetto kids are as educable as other children and that the problem tends to be the school, not the student.

Teachers’ unions oppose alternatives to traditional public schools, regardless of effectiveness, because a union’s primary concern is the welfare of its dues-paying members, not students. For the NEA, the AFT, and the politicians who carry their water, public education is first and foremost a jobs program for adults. Teachers’ unions fight so hard to keep bad schools from closing and poor kids from leaving them because those schools mean jobs for their members. The quality of the education is a secondary concern—which makes the education establishment’s argument that it is philanthropists who are acting out of self-interest especially, well, rich.

When John Paulson announced his multimillion-dollar charter school donation to help New York City’s Success Academy network expand, he pointed out that a decent education was “the best way to reduce poverty long term” and that “Success Academy’s proven record in improving the quality of education for our neediest children has been extraordinary.” But Paulson got the Rockefeller treatment from a union front group called Hedge Clippers, which targets financiers trying to expand school choice for the poor. “What he is doing is neither charitable nor noble,” said the organization in a statement. “He is using his so-called philanthropy as a convenient tool to whitewash his image and appear as the savior of low-income children.”

Michael Mulgrew of the United Federation of Teachers, the New York City affiliate of the AFT, accuses parental-choice philanthropists of “trying to turn schools into profit centers.” Hazel Dukes, an NAACP official, says that hedge-funders are “hijack[ing] the language of civil rights.” And the education historian Diane Ravitch, referring to the efforts of Gates, Broad, the Waltons, and other deep-pocketed supporters of school reform, has warned that “the question of democracy looms large as we see increasing efforts to privatize the control of public schools.” Ravitch adds: “Some think they are leading a new civil rights movement, though I doubt that Dr. King would recognize these financial titans as his colleagues.”

The notion that the new education philanthropists want to line their pockets is unfounded—these dollars, by and large, flow to nonprofits—and the source of Ravitch’s “doubt” is unclear. Martin Luther King was a graduate of Morehouse College. His mother attended Spelman. Both schools owe large debts of gratitude, if not their existence, to the Rockefeller fortune. King’s father attended Dillard University in New Orleans, which enjoyed the patronage of Rosenwald. There is no reason to believe that King didn’t share the same appreciation as contemporaries like Julian Bond of the crucial role that these “financial titans” played in educating black people. Similarly, Booker T. Washington and W. E. B. Du Bois had their philosophical differences, but they shared an appreciation for supporters of black education willing to upend the status quo. “The death of Julius Rosenwald,” said Du Bois in 1932, “brings to an end a career remarkable especially for its significance to American Negroes.” Since then, the careers of other remarkable philanthropists have continued to offer better life chances for disadvantaged black children.

Top Photo: Hedge-fund manager John Paulson, who donated $8.5 million to Success Academy in 2015 (FRED R. CONRAD/THE NEW YORK TIMES/REDUX)