Back in 1966, when I was a senior at New Rochelle High School, my friends were flabbergasted when I told them that I’d be going to Pomona College. I was an okay student—hardly a star in our nerd group—but who’d have guessed that I’d be reduced to going someplace no one had heard of? Zach Bloomgarten was heading to Princeton; John Stanley (aka “Child of Knowledge”) to Cornell; Jimmy Richmond was off to Harvard. But, as the joke soon went, “Stein’s going to an agricultural school.”

“It’s out in California,” became my shorthand explanation, to relatives and the few others who pretended interest. “It’s one of five schools in the Claremont”—brand-new word here—“consortium.”

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

“Oh, okay.” Pause. “Then maybe after a while, you’ll transfer, right?”

There’s a lot less of that these days, of course, with the fixation on where a kid will go to college often beginning at birth. Even those who know nothing else about Pomona often know that it regularly appears on lists of the top small colleges, along with schools like Amherst and Swarthmore. In fact—take this, Child of Knowledge!—it is currently rated Number One overall in the Forbes college rankings. “Oh, yeah, great school!” is what I’m far more apt to hear now.

But here’s the irony: back then, in its relative obscurity, Pomona really was a great school. This wasn’t because it was tough to get into, which, if you were a Californian, it actually was—it’s likely that I got in only via affirmative action, i.e., geographical balance—but because it was a serious place, committed to high standards, as reflected in the quality of its faculty and the breadth of its curriculum. Even if, like me, you were a liberal arts major with only the vaguest of notions of what to do after you graduated, you were pretty sure to emerge at least somewhat well-rounded, having been exposed to a range of competing ideas and challenged in unexpected ways.

Now? “What’s happened at Pomona,” observes a somewhat younger long-ago grad, who maintains professional ties to the school, after we’d shared reminiscences of Mr. Poland’s legendary French Revolution seminar, “is the same as what’s happened at a lot of other schools—except maybe even more so.”

Which, given the competition, is some indictment! But no one who’s followed the devolution of Pomona over the years will find much reason to doubt such an assessment—not with militant leftism and the celebration of victimhood increasingly dominant features of campus life, and dissent from reigning PC orthodoxies increasingly unwelcome. When the nation’s campuses erupted this past fall, with student social-justice warriors issuing ever more strident threats and demands, it’s no accident that Claremont was prominently involved, along with Missouri and Yale. The only surprise was that Claremont’s ground zero wasn’t Pomona; or single-sex Scripps, a bastion of strident feminism; or proudly radical Pitzer; but Claremont-McKenna, long known as among the more ideologically diverse liberal arts schools in the country and, within Claremont itself, challenged for that designation only by math- and science-focused Harvey Mudd.

As at Yale, the initial protests at Claremont-McKenna involved Halloween costumes, here touched off by a photo of the school’s junior-class president, Kris Brackmann, alongside a pair of fellow students dressed in ponchos and sombreros. In a flourish right out of the Cultural Revolution, Brackmann not only met the militants’ demand that she resign but also urged that anyone misguided enough to support her instead “learn from my mistakes in order to best help me create a safe environment for everyone.”

But it was what came next—the public exposure of a private e-mail from Assistant Vice President and Dean of Students Mary Spelling to a Mexican-American student—that truly sent the Claremont community around the bend. An ostentatiously sensitive progressive, with a particular commitment to “fighting campus rape culture,” the dean had sought to express her sympathy for the student’s sense of isolation as a minority. “We have a lot to do as a college and a community,” she wrote. “Would you be willing to talk to me about these issues? . . . We are working on how we can better serve students, especially those that don’t fit our CMC mold.”

Don’t fit our CMC mold! This could not stand! Following furious protests led by CMCers of Color, the hapless administrator threw in the towel, with the usual helping of self-abnegation, noting that she hoped that her decapitation would “help enable a truly thoughtful, civil and productive discussion about the very real issues of diversity and inclusion facing Claremont-McKenna, higher education and other institutions across our society.”

Not that this was about to satisfy the crybullies. They saw the problem as going far beyond one ham-handed liberal administrator; the real issue was the deep-seated racism of the institution itself. And we were off to the races, with students at the other schools, in turn, issuing demands of their respective administrations. Pomona’s, presented to President David Oxtoby by “a group of marginalized students who have not been served by Pomona College,” included the “hiring of full time counselors who are specially trained in queer and trans mental health issues,” the establishment within two years of a Native American and indigenous-studies department, and a department of disability studies, and ensuring that, by 2025–26, at least half of all tenure-track faculty positions be set aside for underrepresented minorities. Yet, for many of us Claremont grads taking in the spectacle from afar, there was in the reports a saving grace—indeed, even reason for pride.

WE DISSENT, screamed the Zolaesque headline of the November 13 editorial in the Claremont Independent, the schools’ conservative paper, and it truly was a cri de coeur. Written as a letter to the community, it condemned the militants who brooked no dissent or even dialogue, ramming their ideology down others’ throats, as well as the craven administrators who let them get away with it. Yet also, it concluded, “we are disappointed in students like ourselves, who were scared into silence. We are not racist for having different opinions. We are not immoral because we don’t buy the flawed rhetoric of a spiteful movement. We are not evil because we don’t want this movement to tear across our campuses completely unchecked. We are no longer afraid to be voices of dissent.”

The Independent’s editor and coauthor of the editorial, Pomona junior Steven Glick, admits being taken aback when he arrived in Claremont from his home in Chicago for freshman orientation. “The first day, we got together in groups to go over everyone’s list of triggers and their preferred gender pronoun. I was shocked, couldn’t believe these were real things that people actually did, but it immediately drove home that that’s the way it is at the school, the accepted set of norms.” Still, he says, since he avoids liberal arts classes and hangs out with fellow economics majors and athletes, the political correctness affects him less than it otherwise might; and, while it’s safe to assume that every new acquaintance will lean left, the militant activists remain a minority. This was apparent in the reaction to the editorial. “All we said was, ‘Hey, not everyone supports these protests,’ and we got a lot of support for saying it. Because some people actually do want to be able to talk freely about these kinds of issues.”

On the other hand, Glick had a job at Pomona’s writing center, working with students needing help on papers, and in December, his boss called him in and told him that his presence there “made it hard for it to be a safe space.” Glick’s shift was canceled, and he was given an essay to read: Andrea Smith’s “Heteropatriarchy and the Three Pillars of White Supremacy.”

I arrived at Pomona in the fall of 1966, and left in May 1970, skipping graduation to head back home, via Las Vegas, in Wamba, my beloved ’62 Pontiac Tempest LeMans convertible. What happened in the intervening time was as dramatic as the rise in tuition from my freshman year’s $1,600 to 2015’s $47,620. For, as at so many schools, those years began the process that has inexorably led to where we are today. I had never been in California before, and I recall my surprise at how little the campus resembled those of the ivy-covered schools familiar from the movies. But the charms of the place quickly grew on me. There was the lovely weather, of course, and the distinctive scent of eucalyptus-lined streets, and, after the first heavy rain briefly banished the smog, the startling appearance of majestic, snowcapped Mount Baldy looming just 15 miles away.

The kids were different, too, sometimes even in how they expressed themselves. I’d never before heard “bitchin’ ” as an expression of approval, for instance, or “back East,” to indicate everything on the map to the right of Colorado. Even more striking, while not necessarily more earnest than the ones from home, the local students were far less given to cynicism or irony. It’s no coincidence that over those four years, every one of my closest friends would end up hailing from back East.

The bigger shock, and disappointment, was Pomona’s conservatism. By 1966, Vietnam had been the dominant issue in progressive circles for several years; a red-diaper baby, I’d picketed the White House and marched down Fifth Avenue with thousands of others, chanting, “Hey, hey, LBJ, how many kids did you kill today?” But at Pomona, it might as well still have been the 1950s. Most even dressed that way. With a handful of exceptions—including the student-body president, as deceptively clean-cut as everyone else—no one seemed to give a damn about the war.

I don’t want to take undue personal credit, or blame, for all that followed. But if the antiwar movement at Pomona can be said to have had a father, I was the father’s sidekick. The guy in question was named Andy, and he lived across the hall in the freshman dorm. As the son of a Wall Street trader from Scarsdale, he was a natural confrere; for though he was for the war, he was at least interested enough to argue intelligently. He was also a born entrepreneur, which is why he approached me one afternoon with a moneymaking scheme. Since candlelight vigils for peace were happening on other campuses around the country, he observed, why not organize one here? We could buy, say, 500 candles wholesale and sell them at double the cost.

And that’s exactly what we set about doing, scooting into L.A. to make the buy, and spreading the word about the upcoming event. A few days before the big night, we even got word that the local weekly, the Claremont Courier, wanted to interview us.

The reporter turned out to be only a few years older than us, maybe 22, and very pretty, and also a fan. “I think what you guys are doing is just great,” she began. “So tell me, when did you turn against the war?”

“Oh, I’ve been against it for a while.” I said. “Pretty much from the beginning.”

“What about you, Andy?”

I’ll never forget the quick, desperate, please-don’t-give-me-away look he shot me. “Uh, well, it’s actually just lately I’ve turned against it.”

The vigil was a huge success, both commercially and ideologically. In its aftermath, seemingly in a nanosecond, even (and sometimes especially) the otherwise politically indifferent were all in with the notion, as one of the era’s slogans had it, that “war is not healthy for children and other living things.” The evolving zeitgeist was such that a confident anti-warrior—say, me—could sit down beneath the Orozco mural in Frary Dining Hall, and over the course of a lunch, throwing around references to the works of Bernard Fall and the idea that Vietnam was a civil war, walk away with two or three quasi-solid converts. Attendance steadily grew at the weekly “silent vigil for peace” on the lawn in front of The Coop, and soon lots of beards were sprouting on campus, including mine, as well as the female equivalent of longer, straighter hair. Though the frats, holdouts of the old order, still held keggers, there was also plenty of grass—better stuff, so it was said, than that to be had back East, since we were so close to Mexico.

“As ‘student journalists,’ we were ideally positioned to cause trouble, and soon found an excellent way to do it.”

To be a conservative, recalls the only out-and-proud one I knew personally, an improbably upbeat kid in my dorm named Bob Loewen, now a retired corporate attorney, “was social poison. If you wanted a date”—he pauses—“let’s just say it wasn’t helpful. Every once in a while, I bump into someone from those days, and they confess that they were a little more right-wing than they let on. But there certainly wasn’t any organized opposition to what you guys were doing. Basically, I was reduced to watching it happen.”

How militant were we? By the standards of the day, not very, and certainly not at the beginning. Our Students for a Democratic Society chapter consisted of a single member, Jim Miller, currently professor of politics and liberal studies at the New School of Social Research in New York and author of, among other titles, the definitive work on Michel Foucault. Grinning maniacally, Miller would show up at otherwise staid demonstrations waving a huge black flag of anarchy.

Then, toward the end of my freshman year, a group of us were able, by default, to take over the moribund Pomona weekly. Founded in 1889, a mere two years after the college itself, Student Life advertised itself as “The Oldest College Newspaper in Southern California” but lately had been wholly supplanted by the Collegian, a daily that was jointly produced by students of all five schools.

Our editorial stance may be neatly summed up by the headline of a piece in our first issue by the paper’s new coeditor, my pal Andy: NO MORE WAR. But that doesn’t entirely do justice to the paper’s sensibility, because from the start there was also a certain antic quality to our efforts. We’d publish anyone with a point of view on just about any subject and, if we had a blank space, throw in a World War I–era ad featuring the Kaiser or cigar-smoking doughboys. Jim Miller, who’d soon be writing for the newly born Rolling Stone, was our rock critic.

Nonetheless, as “student journalists,” we were ideally positioned to cause trouble, and soon found an excellent way to do it. A major issue on the Pomona campus just then, as (in the monkey-do ethic governing such things) at universities around the country, was access to schools’ placement facilities—specifically, whether potential employers deemed objectionable, including the U.S. military, should be allowed on campus to interview and recruit interested students. At Pomona, the issue took on particular resonance at the end of that first year, when eight or ten antiwar students—not me, as I had an art-history final that morning—invaded the interview room to prevent representatives of despised Dow Chemical, makers of napalm, from performing their assigned task. Then, as the company reps drove off, the protesters followed them in their own cars all the way onto I-10, horns honking in triumph.

In response, Pomona’s genial longtime president, E. Wilson Lyon, immediately issued a statement of shock and regret, noting that Pomona’s placement office was nonpolitical, so open to all comers.

And we had our issue.

Early the following school year, an enterprising Pomona student contacted the Communist Party of Northern California, suggesting that it request use of Pomona College’s placement office. A copy of the Communists’ letter arrived at our office the same day the administration received the original. We immediately reproduced it on our front page, beneath the banner headline: COMMUNIST PARTY MAY RECRUIT.

Addressed to the school’s “placement officer” and signed “Albert J. Lima, Chairman,” the letter claimed to seek “at least four students from your school” to help recruit agricultural workers into the CP, at a wage of $40 per week. “As you may know,” it read, “our organization has fraternal relations with a world movement which, in fifty years, has already been successful in leading Socialist revolutions in nations totaling over one billion people. In addition, hundreds of millions of people in other countries look to the Communist movement for their ideas for social revolution. Altogether, our movement now represents the viewpoint of the majority of people in the world.”

Before copies of the issue even arrived at the homes and offices of the many prominent Pomona alums to whom we’d dispatched them, President Lyon issued a statement to the effect that under no circumstances would the Reds be coming, since “the placement office cannot be used as a medium for political propaganda.”

With air force recruiters due several weeks hence, the placement-office issue soon consumed the campus. While by now, a vast majority of students (and also faculty) opposed the war, many felt it wrong to deny interviews to those who wanted them; and there was a further split among those in the ban-the-air-force camp between the majority (characterized by us militants as spineless wimps), who planned silently to picket outside the building, and those willing to put our asses on the line, in the current vernacular, and shut the interviews down. For, indeed, as our classmate and future New York Times editor Bill Keller ominously reported in the Collegian, the administration had deemed any obstructive demonstration “a major offense,” which would “make a student subject to suspension or expulsion.”

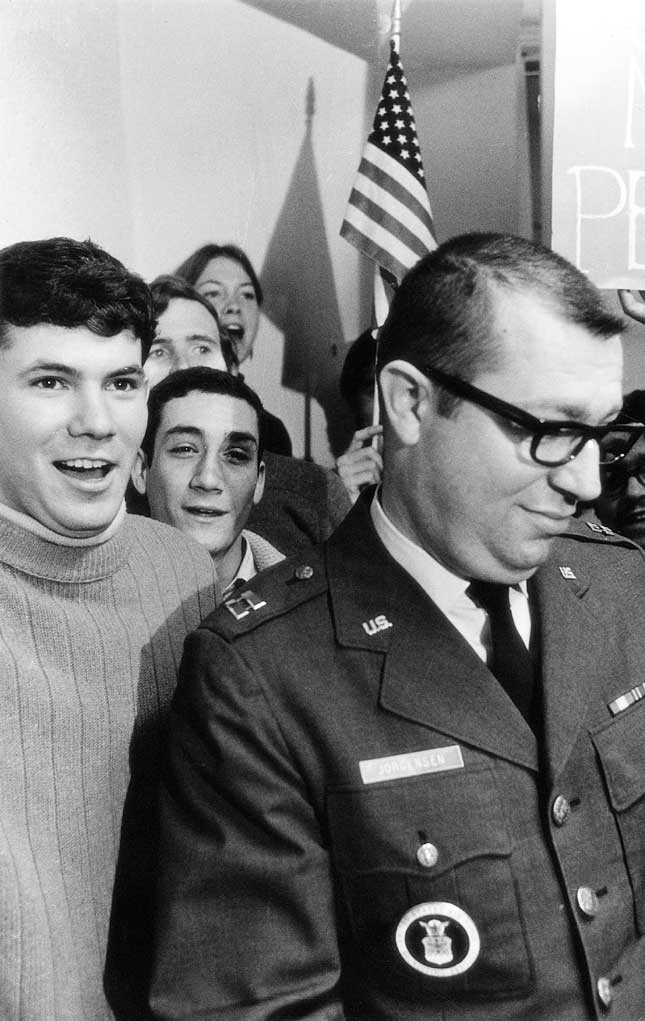

STUDENTS COMPEL AIR FORCE TO HALT RECRUITING IN POMONA, read the headline in the Los Angeles Times on February 22, 1968, beneath a photo of a glum air force captain, F. H. Jorgensen, surrounded by demonstrators—among them my girlfriend and, head cropped at glasses level, me. The piece notes that 75 of us had squeezed into the interview room, all of us giving our names “for submission to men and women student judiciary councils.”

“On some level we still felt like children, testing boundaries and acting out. Were the adults this unsure of their values?”

The trial was the following week, in one of those huge lecture halls with banked seating. After a couple of hours, however, with our codefendant/defense counsel—who’d go on to become a prominent activist lawyer in the area—effectively putting the war on trial, the officials shut the proceedings down, and instead had each of us spend five minutes or so before a student/faculty judicial board. With the verdict preordained, the only question was the sentence, and we awaited it with grim resignation.

Then the announcement came. “Suspended suspensions!” I enthused, to one of my codefendants. “Can you believe it?” He laughed. “Know what that means? We were guilty, but they liked our crime!”

And yet, welcome as was the reprieve, I’m guessing that I wasn’t the only one in our circle whose relief was tinged with something oddly like contempt. Had we really gotten away with it this easily? For all our posturing, and much as we hated the war, on some level we still felt like children, testing boundaries and acting out. Were the college adults this unsure of their values?

In some not yet perceptible way, this event, and the administrators’ reaction to it, was a turning point for Pomona, as were similar surrenders around the same time at innumerable other schools. Not only was in loco parentis about to go the way of all flesh in the dorms—where guys, once banned from girls’ rooms, would soon be spending the night—but so, too, would traditionalists be in retreat in almost every other realm.

While the women’s movement was still a few years off—“Chicks up front!” came the cry at any demonstration where violence was possible—at Pomona, the proximity of the Black Panthers would be a particular spur to black militancy. On the few occasions when a cadre appeared on campus, resplendent in their black leather jackets and berets, grim-visaged—carrying rifles!—we felt the same awe and whiff of danger as Tom Wolfe’s radical chicists in Leonard Bernstein’s living room; and it goes without saying that we shared their certainty as to the justice of the Panther cause.

Claremont’s first black-studies class was, as I recall, offered at Pitzer. My girlfriend took it—and even she was shocked by the ferocity with which the instructor, a militant from L.A., regularly berated two students in particular: the daughters of, respectively, General Westmoreland and (presumably on the grounds of income alone, for he was one of Hollywood’s great liberals) Burt Lancaster.

Though the war—and the ousting from campus of ROTC—remained the focus of white activists, the school’s overwhelmingly middle- and upper-middle-class blacks, taking on the dress and menacing mien of the Panthers, increasingly segregated themselves; and we were delighted in being welcome to stand with them in demanding the expansion of black studies. By the end of my junior year, the trustees caved and voted to establish a black-studies center.

Today, in concert with the other schools, Pomona offers majors in Africana, Chicana/o-Latina/o, Asian-American, and, needless to say, gender and women’s studies. Students inclined to question the prevailing orthodoxies are also well advised, as one puts it, to “tiptoe around the landmines” in other liberal arts departments, where, as at myriad other schools, aging leftist faculty perpetuate their hegemony by hiring and promoting only ideological soulmates. It’s all too depressingly apparent in a Pomona course catalog heavy with the verbiage of the social-justice movement. There’s Religious Studies 184—Queer Theory and the Bible; Art History 133—Art, Conquest and Colonization; Music 072—Gendering Performance; French 151—Men, Women and Power; Economics 121—Economics of Gender and Family; and on and on and on.

The faculty in my department, government, were certainly left of center,” recalls Bob Loewen, of his days as a lonely Pomona conservative. “But compared with today, it was the very model of balance. Not only did no one hold your politics against you; they were genuinely interested in your point of view. We’d have these really honest back-and-forths, and walk away and smile and still be friends.”

The changes in Pomona’s approach to its educational mission were, to be sure, gradual, and often subtle, invariably coming with pro-forma pledges of allegiance to free speech and open inquiry. Living across the country, watching with only one eye, I’d usually be caught short, learning of some new controversy roiling the place. Some were merely ridiculous. There was, for instance, the furious 2008 storm over the school song, the utterly inoffensive “Hail, Pomona, Hail,” on the grounds that it was allegedly first performed in a 1909 minstrel show. (The result: while the song was banned from events involving current students, the administration, in deference to the less socially conscious—but wealthier—grads who’d leaped to its defense, allowed that it could still be performed on Alumni Weekend, and so die along with them.)

Other goings-on in far-off Claremont were more unsettling. There was, most notably, the 2004 Kerri Dunn episode, the nation’s first major campus hate-crime hoax, featuring a visiting Claremont-McKenna psychology professor who defaced her own car with racist and anti-Semitic graffiti. Even more revealing than the five presidents’ near-instantaneous decision to shut down classes for a day of reflection and protest against racism in response to the “terrorist” act—a move not undertaken even after 9/11—was their reaction once the fraud came to light, resulting in Dunn’s arrest and eventual imprisonment. As the campus paper reported, Pomona’s president, David Oxtoby, pledged, in concert with his colleagues, “to keep students focused on the issues raised in the campus response” and “to redouble his effort to address issues of racism, homophobia and religious intolerance. ‘I remain committed to the directions of change that we have been discussing over the last several months in order to create a truly diverse and supportive community,’ said Oxtoby.”

In his response to last fall’s disruptions, the Pomona president seemed more conscious than ever of playing to the multiple constituencies of politicized students, alienated alumni, and free-speech advocates among the board of trustees. Having initially “signed off” on the radicals’ demands, Oxtoby issued a statement at the start of the spring semester emphasizing that he wanted to “ensure that Pomona is a place where, while we may not all agree, we respect the right to speak, rebut, and respond.” At the same time, he added, “We will build on the previous announcement of two new positions in Academic and Student Affairs to enhance student support, along with the additional support for student counseling. We will include members of the community in helping plan and implement these steps as we seek the most effective ways to bring about lasting change when and where it is needed.”

At the end of February, President Oxtoby announced that, after 13 years, he would leave Pomona at the close of the 2016–17 school year. He assured the community that until then, he would continue advancing “the college’s key priorities and successful operations of the institution,” prominent among them “working to include diversity and inclusion” and advancing the school’s “commitment to climate neutrality by 2030.”

Coincidentally, the same day as Oxtoby’s announcement, Steven Glick, having been repeatedly attacked by his superiors at the writing center for his views and ultimately placed on probation, posted a letter of resignation in the Independent. “I had hoped that President Oxtoby’s recent statement in support of free speech at Pomona College would be a game changer,” he wrote, “allowing conservative, libertarian, and classically liberal students and faculty to share our honest opinions with our progressively liberal peers who seem to control the sanctioned conversation on campus. Unfortunately, I was naively optimistic. His words carry no meaning if they are ignored and countermanded by Pomona’s faculty and staff.”

“Those of us on the left back then won our war, the aim of which was to institute a broad critique of America and its values.”

Living and working in nearby Orange County, Loewen viewed the shifting ideological scene in Claremont in a way that was more up close than mine and more personal. He was part of Pomona’s much-derided ROTC contingent and, despite personal qualms about the war, would be our only classmate to serve in Vietnam. (I still have a letter to my local draft board from a doctor at Student Health Service saying that an old hernia made me unfit for military service.) Loewen says that he occasionally would come back to campus, to see old friends or mentor students. “But the last time I was invited was about 20 years ago, after they finally dropped ROTC, and I told them I wasn’t going to donate any more money.”

For all that, he looks back on the place more fondly than I do. Growing up in Northern California, the son of a father who quit school to work, he was the student-body president of his high school and was seen as the family hope. “It was hard for my parents to send me to Pomona—I learned later that there were loans that were difficult to repay,” he says. “But they got value for that.” He remembers “taking Mr. Koblik’s Swedish history class and his saying that he knew that nobody would read everything on that vast reading list but that we should hold on to it because we’d come back to it. And that’s what Pomona did: it gave me the bug to think, and to read, and the structure to do it, and the sense that we’re all part of the same civilization.”

Catching up—or, more accurately, finally talking about these things, from the same perspective, in our relative dotage—we moved on to today and the college’s heedless embrace of all things multicultural. “There’s now this presumption that the black kid and the white kid in the same dorm aren’t part of the same culture,” he observes, “and that’s a load of crap! I get that certain things are unfair, but Western culture enables a dialogue about that. We believe in free speech, we believe in civil liberties, and we’re respectful toward one another—I got that, too, going to this college.”

Unlike me, Loewen is part of the Listserv that some of our classmates started a while back. “What’s funny is how often people still talk about Vietnam,” he laughs ruefully. “We’re the only generation that congratulates itself on losing our war.”

Actually, no, those of us on the left back then won our war, the evolving aim of which was not just to withdraw from Vietnam but to institute a wide-ranging critique of America and its values.

“Remember our senior year,” asks Loewen, “when Nixon bombed Cambodia and it was like there was no greater event in the history of mankind? And the faculty voted to close down all the campuses?” I remember. In fact, a group of us occupied the ROTC building and, in what we thought of as a delightful irony, spent the whole night playing Risk, the game of world conquest. “Well,” continues Loewen, “there’s something that has really stuck with me. There was a young philosophy professor at Scripps—he later moved to Claremont Graduate School—named Harry Neumann, who I heard was still holding class that day. He was jeopardizing his whole career doing this, taking the risk of being denied tenure, so a couple of us headed over there. It was a seminar on Nietzsche, and in addition to its nine or ten students, there were 40 or 50 others hanging around the walls of this little room. What he was discussing was indecipherable to me, but finally he looked up, acknowledging that all these other people were around. And he said: ‘At the faculty meeting yesterday, somebody asked me when, if ever, I would close the university. And I told him: When all the answers to all the important questions have been found, then it would be appropriate to close the university. And for all the people who have all the answers to all the important questions, the university is already closed.’ ”

Top Photo: Student protesters helped shut down air force recruiting on the Pomona campus in 1968. (PRIVATE COLLECTION OF HARRY STEIN)