In 1991, New York’s venerable African-American congressman Charles Rangel met National Review founder William F. Buckley, Jr., for a televised debate. Their conversation centered on topics—race, crime, criminal justice—still prominent in American politics today. But a viewer born in the intervening quarter-century might be surprised at some of the positions taken in their conversation; or, rather, at who held which positions. Buckley, the conservative intellectual, argued that the so-called war on drugs had failed and that the criminalization of narcotics was the primary cause of much of the violence plaguing America at the time. Rangel, whose congressional district was the epicenter of the crack epidemic, argued for increased enforcement of the drug laws, lamenting the government’s lackadaisical approach. Using language that today would be considered inflammatory, Rangel called for drug offenders to face life sentences in prison. “We should not allow people to distribute this poison without fear that they might be arrested, and put in jail. . . . [Those people] should believe that they will be arrested and go to jail for the rest of their natural life.” It’s hard to imagine a liberal black politician making such a statement today. And Rangel himself—who, at 86, will retire from Congress in January—has retreated from his legacy as a law-and-order drug warrior as political momentum on the left has swung against such efforts.

Throughout a career spanning more than 50 years, Rangel has been an effective advocate for New York, steering federal money to the city for everything from mass-transit infrastructure to post-9/11 reconstruction. He’s also been embroiled in numerous scandals, from his illegal tenancy of four subsidized apartments to his failure to declare income from rental property that he owns in the Dominican Republic to his use of franking privileges to raise money from people with business before his committee on behalf of the Charles Rangel Institute at CUNY. But over the course of his long career—one in which he accumulated tremendous power, perks, and influence—Rangel was never more right than when he pushed for public order and crime-fighting. It’s likely, however, that he won’t be remembered for this but instead for his cronyism and political featherbedding, which he pursued with guile and consummate skill.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

Rangel was just the second African-American to represent Harlem in Congress. Given historical voting patterns, he might turn out to be the last for some time. In 1950, central Harlem was 98 percent black; today, the neighborhood’s black population is 60 percent and falling. Greater Harlem, stretching from river to river, from 106th Street to West 155th Street, was majority black from the mid-1920s until 2000, but it is now mostly nonblack, with a sizable Latino population, and rapidly growing white and Asian communities are settling there as well. Rangel’s two-time failed challenger Adriano Espaillat, a New York state senator born in the Dominican Republic, won the primary election to succeed him over his handpicked successor, Assemblyman Keith Wright, son of one of Rangel’s early mentors. With a general-election victory in the overwhelmingly Democratic district a mere formality, Espaillat will become the first Dominican-American in Congress.

Rangel’s retirement reflects the decline in Harlem’s centrality to the black experience in America. When Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. assumed the newly created seat in 1946 as the first black congressman from New York State, Harlem was still the cultural and political capital of black America, the “center and symbol of the urban life of the Negro American,” as Daniel Patrick Moynihan wrote. The promise of Harlem as a black urban utopia had faded by the mid-1960s, when urban decay was taking its toll. Crime in New York, which began to spike in 1965, was consistently much worse in Harlem, where the rate of juvenile delinquency was double the citywide rate, murders were six times the city average, and drug addiction ten times that of the city as a whole.

Harlem did, however, have Powell, who, by 1961, had ascended to the chairmanship of the powerful Education and Labor Committee in Washington. Over the next six years, Powell’s committee shepherded an estimated 40 percent of all legislation enacted by the House. The brilliant, flamboyant minister/lawmaker marked up and pushed to the floor a wide range of New Frontier and Great Society legislation. But by the late 1960s, Powell was in trouble for misusing committee funds, taking attractive secretaries on fact-finding missions to investigate Parisian nightclub practices, and refusing to pay a civil judgment stemming from a slander charge. In 1967, Congress refused to seat Powell, leading to a special election. When a Supreme Court case decided in Powell’s favor, he was ultimately seated but stripped of his seniority and his committee chairmanship. Living almost full-time in Bimini, showing up neither in Washington nor in New York, Powell lost his glow among his troubled constituents, who were desperate for effective representation in Congress.

Looking for a capable replacement for Powell, Governor Nelson Rockefeller settled on Rangel, a savvy second-term assemblyman who had proved himself politically adept and adaptable. Close allies with Manhattan borough president Percy Sutton and fledgling state senator Basil A. Paterson, Rangel had demonstrated his ability to negotiate Harlem’s byzantine power structure. He formed a new power bloc that, with the addition of Assemblyman David Dinkins, became known as the “Gang of Four,” establishing a dominant role in New York politics.

A native Harlemite, Rangel was a decorated marine who served valiantly in the Korean War and then put himself through college and law school while working as a hotel desk clerk. Positioning himself between the reform and regular wings of the Harlem political machine, Rangel had maneuvered himself into an assembly seat in the 1966 election, when he caught Rockefeller’s eye. Rangel carried legislative water for Rockefeller and took political heat as well, as when he backed the governor’s proposal to build the Harlem State Office Building on 125th Street over the fierce opposition of local protesters. Rockefeller promised to finance Rangel’s run against Powell, and even gave him first crack among the New York delegation at redrawing the district’s lines to his liking. Rangel won the 1970 Democratic primary by 150 votes and went on to win the seat in November. Aside from his first reelection campaign, he would not face serious opposition for another 42 years.

Entering Congress in January 1971, Rangel set about his life’s work: entrenching himself and his associates in power by leveraging state and federal funding for antipoverty programs and economic-development schemes. One of his first moves was to take over the board of famed Harlem social-services provider Haryou-ACT, which had been a source of much of Powell’s clout. Inveighing against “poverticians” who had corrupted the organization, Rangel replaced the Haryou board with his political allies, who thus had sole responsibility for directing tens of millions of dollars in antipoverty funding annually. Rangel and his coterie retained control over this plum until Ed Koch’s election as mayor in 1977; Koch, who popularized the term “poverty pimp,” cut welfare spending and centralized control of state and federal funding for community-based organizations. In his memoir, Rangel accuses Koch of being “totally insensitive to the yearning of black New Yorkers for respect. . . . He refused to accept my advocacy for a larger black slice of the pie.”

Despite losing control of Haryou, Rangel found other pies to cut slices from. In 1971, New York State created the Harlem Urban Development Corporation as a subordinate arm of the state Urban Development Corporation. HUDC was Rockefeller’s effort to demonstrate good faith regarding black economic self-determination. From the start, the parent organization took a laissez-faire approach to oversight. In 1976, under Rangel’s supervision, the HUDC secretly rewrote its bylaws, establishing independence from the UDC; five years later, the split was formalized, and the HUDC was given free rein. With no outside supervision—but a secure flow of funding from Washington and Albany—the HUDC began spending money on a grand scale.

“Millions of dollars for economic development were funneled through the Rangel-controlled HUDC and disappeared.”

For more than a decade, millions of dollars allocated for the economic development of Harlem were funneled through the Rangel-controlled HUDC and disappeared. A 1997 state investigation, ordered by Governor George Pataki after the HUDC was dissolved, found that the organization “spent untold unnecessary amounts of taxpayer funds, failed to properly account for loans and advances to HUDC directors and employees, and pumped millions of dollars into New York’s underground economy through ‘off-the-books’ payments.” All told, the entity spent more than $100 million (in unadjusted dollars) of public money without developing one successful project.

Rangel coordinated the HUDC’s work with his role as an elected federal official. A longtime proponent of increased trade relations with African and Caribbean nations—he sponsored legislation such as the 2000 African Growth and Opportunity Act and the 1984 Caribbean Basin Initiative—Rangel originally conceived of the Harlem International Trade Center Corporation (HITCC) in 1978 as a $200 million, 44-story office complex that would attract business executives from developing countries to establish their offices on 125th Street, which the New York Times in 1989 called the “unofficial capital” of the Third World. Rangel legislatively forced the federal General Services Administration to commit to leasing 200,000 square feet of office space in the proposed center; the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey also agreed to lease space in the HITCC after Governor Mario Cuomo threw his support to the project in 1986. In his memoir, Rangel dismisses Cuomo’s “remarkable, dead-end career” but acknowledges that the governor “had been very, very good to me, as far as my effort to establish the Harlem Trade Center.”

Twenty years of planning and preparation for the International Trade Center resulted in $6 million spent on “consultants, architects and travel expenses” but nothing else. Throughout this period, Rangel was more than just a nominal member of the HUDC board. William Stern, former chairman of the New York State Urban Development Corporation, recalled wondering why Harlem, unique among New York City neighborhoods, had its own Urban Development Corporation: “I called Cuomo’s chief of staff, Michael Del Giudice. I asked him for the story on HUDC. He said, ‘Bill, HUDC is Charlie’—Charles Rangel, that is, the longtime congressman from Harlem. HUDC was a patronage machine for Rangel’s local cronies.” (See “Sorry, Charlie,” Summer 1997.)

The fate of the Tree of Life bookstore on 125th Street provides a sad footnote to the Harlem International Trade Center debacle. A late-1960s addition to Harlem, the Tree of Life was a popular bookshop, reading room, and community center that offered classes on yoga, herbology, spirituality, and economic self-sufficiency. The store opened when most of 125th Street was boarded up and dilapidated. Calling itself the University at the Corner of Lenox Avenue (UCLA), it was patronized by such luminaries as Muhammad Ali, Pete Seeger, and Ruby Dee. A court battle arose when the HUDC wanted to condemn the store’s site to make way for the Harlem International Trade Center. After several years of litigation, the HUDC won out, and, as the Times reported in 1980, “bulldozers reduced the store to debris so construction of an international trade complex would not be hampered.” The store was demolished for nothing, as it turned out.

Down the street stands the legendary Apollo Theater, a music hall that featured every great black entertainer from the 1930s through the 1970s. After intermittent efforts to keep it open, Inner City Broadcasting, Percy Sutton’s media company, purchased the theater in 1981. Immediately afterward, the HUDC agreed to invest millions of dollars to turn the Apollo into a cable television studio. Failing to make a profit running the theater, Inner City Broadcasting sold the Apollo in 1991 to New York State, which established the nonprofit Apollo Theater Foundation to run the venue—with Rangel as chairman. Inner City Broadcasting retained the rights to produce the popular syndicated Showtime at the Apollo program, with profits in excess of expenses disbursed to the state to help run the foundation. By 1999, old political allies Rangel and Sutton found themselves in New York attorney general Eliot Spitzer’s crosshairs over $4.4 million that Sutton’s Inner City Broadcasting owed to the Apollo Foundation. Spitzer agreed to seek dismissal of a lawsuit only after forcing Rangel to give up his foundation chairmanship and requiring Sutton and his partners to disgorge $700,000.

Governor George Pataki dissolved the Harlem Urban Development Corporation in 1995 and replaced it with the Harlem Community Development Corporation, which operates under the strict governance of its parent agency, the Empire State Development Corporation. Undaunted, Rangel created a federal version of the same entity. The Upper Manhattan Empowerment Zone (UMEZ), launched in 1995, has enabled an even wider scope of waste, delay, and frivolous expenditures. The idea of “enterprise zones” came out of post-Keynesian trends in British urban planning circles in the late 1970s. Carving out areas within cities that would be free from business taxes and have less regulation could, the thinking went, promote entrepreneurship and economic growth. As the American social-services industry translated the idea, “enterprise” became “empowerment.” Urban-studies scholar Mitchell Moss, explaining the difference in 1995, wrote that liberals “discovered that [empowerment zones] offered a way to channel money into impoverished urban communities, subverting the rationale for the enterprise zone by expanding, rather than reducing, government involvement.”

“Rangel ensured the designation of virtually his entire district as an empowerment zone.”

Rangel ensured the designation of virtually his entire district as an empowerment zone. The $249 million UMEZ provided loans to small businesses and, secondarily, grants to community organizations. In the first five years of operations, the UMEZ made 47 small-business loans, totaling only $4.3 million—10 percent less than it spent on salaries and overhead. It made large loans to national retailers such as Home Depot and Costco, along with major real-estate firms—organizations that don’t usually lack access to credit.

In 2001, Rangel recruited famous Los Angeles attorney Johnnie Cochran, Jr., to become chairman of the UMEZ. The move was openly understood as a means for Rangel to maintain control over the board. Cochran had no experience in upper Manhattan and, when given a tour of the area, was surprised to see that, unlike in Watts, Harlemites lived in apartment buildings instead of houses.

The recent history of the UMEZ is not much different. The board meets sporadically and hasn’t been audited for several years. It rarely makes loans and appears to be hoarding cash, perhaps in order to continue paying rich salaries to upper management. A local businessman, speaking anonymously, claimed that the UMEZ offers loan conditions significantly worse than what can be obtained from local banks. The UMEZ has drifted from its original purpose as an engine for economic growth into a somnambulant entity that mostly distributes grants to politically connected local nonprofits, such as the $2.7 million that it doled out to the Alianza Dominicana, shortly before the organization abruptly shut down.

Obviously, Harlem has undergone a massive positive change in fortune since Rangel took office. But it is fair to say that economic development in Harlem has occurred despite, not because of, his efforts. Speaking of Harlem’s natural advantages, Moss notes that “the strength of the New York City economy made it impossible for Harlem not to develop. The proximity of the area to the core Manhattan business district, the excellent transportation infrastructure, as well as great housing stock and strong local institutions,” combine to make Harlem an obvious locus for positive development. But it’s hard to identify many areas where Rangel deserves much credit for bringing it about, even after half a century of holding state and federal office.

Rangel’s record in one high-profile area of national policy seems completely forgotten. From the early 1970s to the 1990s and beyond, Rangel demanded and fought for an expanded federal role in the prosecution of the war on drugs. In March 1971, he and the newly formed Congressional Black Caucus met with President Richard Nixon to discuss their priorities. Tapes of the meeting reveal Rangel pleading with the president to use his “power . . . as you would if this were a national crisis, and I think we’ve reached that.” The CBC demanded an expanded effort to battle drug trafficking. Four months later, Nixon declared the war on drugs, echoing Rangel’s rhetoric in calling for an “all-out offensive.”

For almost his entire career, Rangel promoted a law-and-order approach to drugs that would, by the standards of today’s anti-incarceration movement, mark him as an extremist. Shortly after his meeting with Nixon, Rangel opposed the provision of methadone-maintenance treatment in New York City, calling it a “colonialist” approach to drug addiction. In 1976, Rangel encouraged the NYPD to form a task force that would focus on combating street-level drug crime in Harlem. In the early 1980s, Rangel railed against the Reagan administration for failing to do more about the drug problem, complaining, “I haven’t seen a national drug policy since Nixon was in office.” As chairman of the House Select Committee on Narcotics Abuse and Control, Rangel pushed for an activist national policy of eradication of coca and marijuana crops at the source throughout Latin America. He strongly supported the 1986 Anti-Drug Abuse Act, which imposed mandatory minimum prison sentences on drug criminals and established the notorious sentencing differential between cocaine in its powder and crack forms. Rangel supported the 1994 Crime Bill, which made gang membership a federal crime, and he long advocated life sentences for drug dealers—and not just for major traffickers.

Thanks to books such as Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, the new conventional wisdom holds that the war on drugs was a thinly veiled war on blacks. The Black Lives Matter movement and its liberal allies promote a revisionist narrative of American criminal justice in which anticrime legislation, particularly regarding drugs, has been a decades-long, targeted effort to destroy people of color. The actual history reveals that black politicians and clergy, responding to pleas for help from the law-abiding majority of their communities, were among the first to demand a firm hand in dealing with the violent crime wave of the 1960s and 1970s. As Michael Fortner explains in The Black Silent Majority, “mass incarceration had less to do with white resistance to racial equality and more to do with the black silent majority’s confrontation with the ‘reign of criminal terror’ in their neighborhoods.”

Harlem’s resurgence has had more to do with the public-safety revolution of the last 25 years—a revolution that Congressman Rangel long supported—than with the failed economic-development organizations that he established and oversaw. As he heads into retirement, Rangel supports decriminalization of marijuana and laments the fact that legislation he helped craft has resulted in “unnecessary” incarceration. If Rangel were honest, though, he would trumpet his vigilance as a crime fighter and drug warrior—and identify, as his living monument, not the site of the phantom International Trade Center but the drug-free street corners of Harlem.

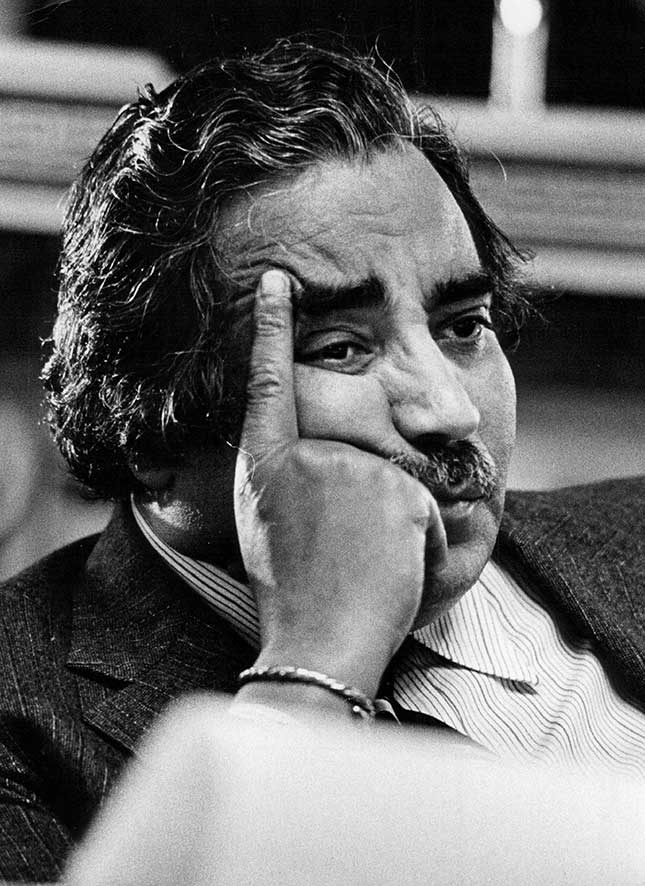

Top Photo: Rangel’s retirement marks the end of an era in Harlem, as political power passes from blacks to Hispanics. (ANDREW LICHTENSTEIN/CORBIS/GETTY IMAGES)