Blue-state defenders say that progressive policies work. After all, liberal-leaning states boast some of the nation’s wealthiest and best-educated populations. But many are also reeling from problems ranging from high costs of living and widening income inequality to chronic fiscal crises. And leading blue states such as California, Massachusetts, and New York possess unique assets—respectively, favorable climate, educational hubs, fortress industries—that shelter them, at least for a time, from the full economic consequences of their public policies. What happens when you go blue in a more average, workaday place? Rhode Island—a blue state in its purest form—provides an answer.

“Rhode Island is in the midst of an especially grim economic meltdown,” a 2009 New York Times story began, “and no one can pinpoint exactly why.” Five years later, the state continues to suffer from most of the same problems the Times story described: high unemployment, a crippling tax structure, dangerously underfunded state pension systems. But contrary to the Times’s claims, Rhode Island’s predicament is easy to explain. With no special economic advantages, the state has maintained an entitlement mentality inherited from an age of colonial and industrial grandeur. Rhode Island was once one of America’s most prosperous states, and its rate of higher-education attainment remains better than the national average. But the state’s key industries collapsed long ago, and its political leadership has refused to make adjustments to its high-cost, high-regulation governance system.

The result: a state with “the costs of Minnesota and the quality of Mississippi,” as Rob Atkinson, former executive director of the Rhode Island Economic Policy Council, told WPRI-TV. Indeed, Rhode Island is arguably America’s basket case, overlooked only because it is small enough to escape most national scrutiny. Its ruination is a striking corrective to the argument that states can tax, spend, and regulate their way to prosperity.

Founded by Roger Williams in 1636, Rhode Island was for a long time a progressive and dynamic place. It enshrined freedom of conscience in an era when enforced religious conformity remained the norm. Rhode Island’s charter is arguably the forerunner of all freedom-of-religion clauses. It recognized Indian land titles and acquired territory by negotiated purchase, not seizure. In 1652, Rhode Island became the first state to ban slavery, though the ban was more honored in the breach. The state abolished racial segregation in 1866. Its tradition of social tolerance continues to the present. Gay marriage was legalized here by the legislature, not by the courts.

Rhode Island was also economically innovative. Positioned with excellent seaport access, small, easily dammed and managed rivers, and a freethinking heritage, Rhode Island became a central hub of the Industrial Revolution in America. It developed into a textile powerhouse—the first textile mill in the United States opened in Pawtucket in 1793—and excelled in jewelry manufacturing and merchant shipping, while also boasting a large naval presence. Newport shined as a premier summer-home destination for the Gilded Age elite, adding a touch of glamour to the industrial grit. All this activity created fantastic wealth in a state that became home to world-renowned institutions such as Brown University and the Rhode Island School of Design. And as with other major industrial centers, Rhode Island attracted streams of immigrants looking to better their lives, especially those from Italy, Portugal, and Ireland. The good times spanned well over a century.

But Rhode Island’s prosperity came with a dark side: an arrogance that persists today. Like Detroit, Rhode Island enjoyed success for so long that it came to believe that it could do whatever it liked, without consequences—even when economic developments started to leave it behind. Perhaps that complacency helps explain why Rhode Island was also a leader in the more dubious areas of corruption and misrule. “It has often been said that Rhode Island has a rich political history,” former Providence mayor—and two-time convicted felon—Buddy Cianci once wrote, “which in fact is a nicer way of saying that in Rhode Island, politicians get rich.” Some say that Rhode Island’s unofficial state motto should be: “I know a guy.”

The culture of corruption and cronyism started early. Both the Federalist and the Anti-Federalist Papers used Rhode Island as a cautionary example. Over a century later, the state proved immune to Progressive Era reforms, and a 1905 jeremiad in McClure’s called its politics “notorious” and “shameful,” lamenting that “Rhode Island was, and it is, a State for sale.”

In the early 1900s, the Republican Party ran the state, wielding power through a Tammany Hall–style political machine. That changed in 1935, when Democrats seized control in the so-called Bloodless Revolution. In a power grab described at the time as “a startling coup” by the New York Times, the Democratic lieutenant governor refused to swear in two Republican senators who had won contested races the previous November. Democrats then declared their own candidates the winners in these elections and, having gained control of the chamber, effectively fired every Republican appointee in the state across 80 boards and commissions in a matter of minutes. The Democrats even sacked the Republican-dominated state supreme court.

The Democratic Party has dominated Rhode Island politics ever since. Democrats have held the state legislature since 1959 and currently enjoy an overwhelming majority there, along with every statewide elected office. Republicans occasionally manage to get elected governor or mayor, but party allegiance hasn’t been strong. Current governor Lincoln Chafee was a Republican senator who became an independent before migrating to the Democratic Party. Cianci originally won the Providence mayor’s office as a Republican before becoming an independent.

Decades of Democratic control have produced systemic corruption—and reliably left-wing policies. Thus, Rhode Island has the full complement of blue-model orthodoxy: high taxes, high social-services spending, powerful unions, and suffocating regulation.

Rhode Island’s state and local tax burden is sixth-highest in the nation, as is its corporate tax rate of 9 percent. This includes a $500 minimum corporation tax levied even on small businesses that lose money. The state’s sales-tax rate of 7 percent is higher than the national average. Rhode Island ranks seventh in per-capita property taxes, and it has the 14th-highest gas tax and the third-highest cigarette tax. While these taxes don’t match California’s or New York’s staggering rates, they are at least moderately high across the board—and their effect is arguably more stifling, since they’re combined with a lower-end economy that makes them even less sustainable.

The state spends only 4.8 percent more per capita than the national average, but its outlays are heavily directed toward “consumption” spending—that is, social services. Former public official Gary Sasse notes that the state spends 52 percent more per capita on human services than average and covers many more Medicaid services than the federal government requires. According to the Council for Affordable Health Insurance, Rhode Island also has more items of mandated health-insurance coverage for private-sector insurance than any other state. The state ranked second on a Daily Finance list of “10 Best States for Unemployment Benefits” while the Tax Foundation ranks Rhode Island’s unemployment tax system as the nation’s most onerous. Stifling successor-business rules mean that entities purchasing, say, the assets of a closed manufacturer in order to reopen a plant can get hit with the previous employer’s layoff costs. Unemployment taxes are also unequally levied, as the system is set up to reward favored sectors. Seasonal tourism-related businesses, for instance, with recurring planned layoffs pay far less into the system than they use. In 2011, the most frequent users generated benefits claims of $88.4 million, while paying only $50.2 million in taxes.

Rhode Island is also one of just five states that require paid temporary disability insurance (TDI). Its maximum TDI benefit levels and duration top all states except California. Companies must participate in the state TDI system and can’t purchase coverage on the open market. Employees, meanwhile, can collect benefits even if they’re already getting vacation or sick pay. The TDI program also guarantees them up to four weeks of benefits per year to serve as temporary caregivers, whether for a newborn or a sick relative. Whatever their merits, these benefits impose heavy burdens on businesses and are far out of line with what other states offer.

Rhode Island’s 16.9 percent unionization rate is the nation’s fifth-highest (the national average is 11.3 percent). In a survey assessing several criteria—including resources and membership, involvement in politics, and perceived influence—Education Reform Now (an affiliate of Democrats for Education Reform) and the Thomas B. Fordham Institute ranked Rhode Island’s teachers’ unions as the fifth-most powerful in the country. Only New York has a higher percentage of overall public-sector union membership. With union might have come glaring abuses of the retirement and disability systems. In Providence, 58 percent of firefighters retire on disability pensions. A TV station discovered a Providence firefighter on disability for a purported shoulder injury lifting weights vigorously at a local gym. A North Providence friend of the mayor managed to get himself hired as a rookie fireman at age 52. He then spent five of his ten years as a fireman on disability leave before obtaining a permanent disability pension—locked in at a higher lieutenant’s salary because he substituted in that capacity for one day.

Its regulatory regime alone would present a formidable obstacle to the Ocean State’s economic vibrancy. Research by Jason Sorens at SUNY-Buffalo found that Rhode Island has the most land-use regulation of any state. It also has a vast array of business regulations. Until last year, Rhode Island was the only state that required businesses to pay their employees weekly. It passed legislation in 2013 to allow biweekly payroll—but only for businesses whose average pay is twice the minimum wage and can post a surety bond, get the written permission of any unions affected, and recertify with the state every four years. Meantime, all the Democratic gubernatorial hopefuls (the election is this November) want to raise the state’s minimum wage to $10.10 per hour, making it one of the nation’s highest.

Building has gotten harder and harder. Grumbles Bob Baldwin, a home builder active in Rhode Island since the 1970s: “In the seventies you could look up the zoning requirements on the map, have your engineer design to that, and get approved in three to six months, max.” Today, it’s a different story. “They’ve changed the zoning to increase minimum lot sizes, even in areas where nothing is currently built to that size,” he says. “Plus, there are regulations that go well beyond the state minimums and vary from town to town.” Some of these building standards mandate high-end materials, such as granite curbs, which drive up costs.

The biggest problem for developers is that the approval process can drag out through endless cycles of reviews and objections. As John Marcantonio, executive director of the Rhode Island Builders Association, puts it: “It’s not one particular rule; it’s death by a thousand paper cuts. The process to develop land in Rhode Island can go on for years.” Baldwin says that local builders now budget for the inevitable lawsuits that will be needed to get projects approved. Worse, after waiting several years for planning approval, developers may have to wait again for building permits.

Underlying all the rules and regulations and taxes is a hostile mind-set among locals to business and free enterprise. As Al Verrecchia, chairman of the board of Pawtucket-based Hasbro, observed recently on Rhode Island PBS: “A part of it is the attitude we have. People want to come in and invest, and, in most cases, the attitude is: ‘Why are you coming in to invest?’ and ‘Why do you want to build a business?’ as opposed to ‘Hey, that’s great. What can we do to help?’ So it’s not so much a specific piece of legislation or the regulatory environment itself; it’s more of an attitude that exists from the top down.” Cheryl Sneed, CEO of Banneker Industries, agreed. “As I compare it to other states we do business in, it’s just easier to do business and quicker to get up and running” elsewhere, she says.

Small wonder that Rhode Island scores poorly in most business-climate surveys—47th in the Small Business Survival Index and 46th in the Tax Foundation’s rankings of business-tax climate.

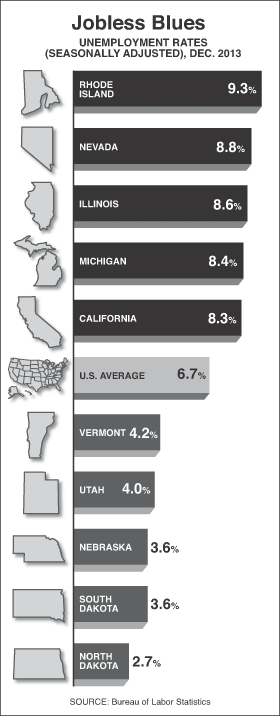

Its blue-state enthusiasms have done the state serious damage. Depending on the month, Rhode Island has either the worst or second-worst unemployment rate in the nation: 9.3 percent, according to the latest Bureau of Labor Statistics figures. Since 2000, the state has lost 2.5 percent of its jobs, and what jobs it has created are mostly low-paying. The job situation is so dire that entire local economies have become dominated by the benefits-payment cycle. In Woonsocket, for example, one-third of residents are on food stamps.

Rhode Island boosters cite its per-capita income of $45,877—4.9 percent above the national average and 14th-best in the country—as evidence of the state’s economic strength. But this number is misleading. It’s driven in part by high levels of government-transfer payments: everything from retirement and disability insurance to workers’ compensation and unemployment, veterans’ benefits, and the whole panoply of federal grants (Medicaid, food stamps, SSDI). Rhode Island ranks third in the country in such transfers per capita. Incomes have also been stagnant for decades. As late as the 1930s, Rhode Island’s per-capita income was nearly 50 percent greater than the national average. By the mid-1940s, though, it had declined to just a tick above the U.S. average, where it remains.

Rhode Island is prohibitively expensive. Those land-use regulations mean that housing prices are high, despite the poor economy. As a rule of thumb, a household should spend no more than three times its annual income on a home. But in Rhode Island, the so-called median multiple—what a median-income family would have to spend to buy a median-priced home—is 4.4 times income. Accounting for high costs, one survey ranked the average wage, adjusted for cost of living in metro Providence (which includes the entire state), 48th out of 49 large regions for which data were available. (Other surveys show the state doing somewhat better.)

The state’s bumbling economic development efforts haven’t helped. One notorious example came in 2010, when the government gave a $75 million loan guarantee to 38 Studios, Red Sox great Curt Schilling’s video-game start-up, to relocate from Massachusetts. The company swiftly went bust. In another dubious project, the state signed a long-term deal for offshore wind power, which will raise its already-high electricity costs, in part because it has agreed to pay rates four times higher than what its neighbors, Massachusetts and Connecticut, will expend in similar renewable-energy deals. According to Rhode Island Taxpayers, the deal amounts to an overpayment of approximately $535 million—far more than the state lost on 38 Studios. Former governor Don Carcieri, a Republican, steered both projects: in Rhode Island, bad ideas are bipartisan.

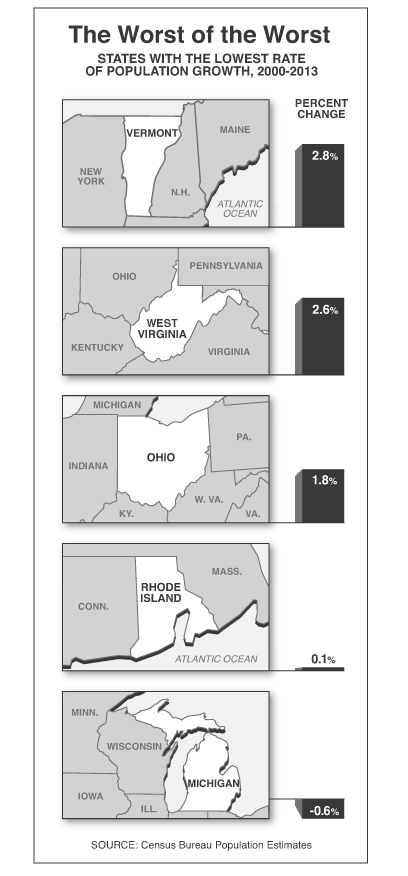

The state is a demographic disaster zone. It grew slightly in population last year for the first time since 2004. Since 2000, Rhode Island’s population growth is second-worst in the country, beating only Michigan. It has the third-lowest percentage of residents under 18 and the highest percentage of any state of residents over 85.

Decades of poor governance have put the state in a fiscally treacherous position. Treasurer Gina Raimondo recently led a successful pension-reform effort, but the state pension system remains woefully underfunded. Local pensions are in bad shape, too, with 23 such plans classified as critically underfunded. Drastic pension reductions in bankrupt Central Falls could provide a preview of coming attractions elsewhere. This includes Providence, where, despite a much-touted union giveback negotiated by Mayor (and gubernatorial candidate) Angel Taveras, the market value of assets in the city pension plan is just $336 million, compared with a liability of $1.2 billion.

With so much money getting gobbled up by pensions and social services, little remains to address the state’s other pressing needs—including infrastructure, much of which is falling apart. An alarming number of bridges require buttressing support, such as stacked railroad ties. Rhode Island ranks fourth-worst in the nation in the percentage of its bridges considered structurally deficient. One major crossing, the Sakonnet River Bridge, recently had to be replaced at a cost of $163 million because of deterioration resulting from a lack of routine maintenance. The condition of roads and highways isn’t much better. With its heavy emphasis on social-welfare spending, Rhode Island ranks 49th among states in per-capita highway spending.

And, of course, there’s that culture of corruption and cronyism, which is Kryptonite to most business. “Why do companies not go to Zimbabwe or something?” Atkinson asked. “Fundamentally, you just cannot trust the rule of law and the government there. I’m not saying Rhode Island is [a Third World, banana-republic government], but they’re in that direction compared to a state like Minnesota, Utah, Washington.” Local analyst Lou Mazzucchelli summed it up: “If Rhode Island were a business, we’d shut it down.”

Even those who acknowledge Rhode Island’s problems might argue that its troubles don’t invalidate the blue-state model. After all, they can say, other New England states have similar policies and haven’t posted such crummy results. That argument doesn’t survive closer inspection, however. Far from being an anomaly, Rhode Island is actually close to the regional norm.

New England’s wealth essentially radiates from two urban poles: one out of New York City and into Connecticut and the other originating from Boston. New York and Boston have entrenched positions in high-value industries, partially buffered from market forces. Wall Street remains the center of the financial industry, and Fed policy has flooded New York’s economy with money. The Harvard- and MIT-anchored innovation complex powers the Boston-area economy. These cities have captive industries bound to their geography and large enough to operate at global scale. Their advantages let them get away, to some extent, with policies that would spell doom elsewhere. Money covers a multitude of sins. To the extent that surrounding metro areas can tap in to New York or Boston money, they do reasonably well. If they can’t, they face tougher prospects. (Hartford’s indigenous insurance industry is a rare exception.)

But while metro Boston is doing well (if growing slowly), the rest of Massachusetts looks much like Rhode Island. Its so-called gateway cities—Springfield, Worcester, Fall River, Pittsfield, and others—have struggled as badly as similar Ocean State burgs. Jim Stergios of the Pioneer Institute described Massachusetts as “Greater Boston and three Rhode Islands grafted onto it.” Beyond the New York metro area, it’s a similar story in the Empire State, where metro areas such as Buffalo, Rochester, Utica, and Syracuse have seen big job losses.

Connecticut, too, has its share of decaying postindustrial cities, such as Bridgeport and New Haven. Even its white-collar economy has performed sluggishly. Numerous vacant office complexes dot the state, which the local NPR affiliate dubbed a “suburban corporate wasteland.” Aetna demolished a 1.3 million-square-foot office complex in Middletown in 2011. As policy analyst Josh Barro wrote in Forbes, “Eastern Connecticut isn’t economically or culturally much different from Rhode Island, but its residents get to live high on the fiscal hog because of tax receipts generated in Greenwich and New Canaan.”

With limited access to New York and Boston money, Rhode Island has paid a steep price for its resistance to change—especially since its economy signaled serious problems long ago. Industrialization hit the state early, with textile mills leaving as far back as the 1890s. That should have sent a message that Rhode Island’s low-skill industries were vulnerable to competition—and that the state’s coastal location and proximity to water power for mills could no longer provide a competitive advantage in an era of coal, steam, electricity, and railroads. Yet even as Rhode Island’s industrial base steadily eroded, the state’s political leaders didn’t seem to understand that they no longer had any marketplace leverage. This myopia continues to the present day. The state’s leaders act as if they’re selling a unique luxury product—à la Michael Bloomberg’s notorious quip about New York City—when they’re selling a commodity, at best. They feel justified in adopting the same arrangements as Massachusetts and Connecticut without the compensating economic advantages that would help pay for such policies, at least for a while. As Atkinson put it: “For a long time, Rhode Island could essentially afford to be inefficient and quasi-corrupt . . . because things just sort of needed to be there. That was gone a long time ago.” Someone forgot to tell the state’s political leaders.

In most places, the question might be: What should we do? In Rhode Island, it’s probably better to ask: What can we do? Change won’t come easily. The state has done so poorly for so long that the public has grown fatalistic—“Rhode Apathy” is how one local described the state of mind. People and groups cling tenaciously to any benefits they get from the current system because they can’t imagine the pie getting bigger. The state is also extremely insular and parochial. The University of Rhode Island’s fight-song lyrics—“We’re Rhode Island born, and we’re Rhode Island bred, and when we die, we’ll be Rhode Island dead”—aren’t far from the truth. In a state the size of a proverbial postage stamp, a remarkable 58.1 percent of its residents were born there. Locals frequently give directions in reference to landmarks that no longer exist. A popular bumper sticker boasts, “I Never Leave Rhode Island.” Allan Tear, who runs local start-up accelerator Betaspring, frequently reminds people that “Rhode Island is not actually an island.”

Many traditional free-market reform prescriptions are politically dead on arrival in such a climate. Nor will Rhode Islanders accept a Texas-style, stripped-down social-safety net. Thus, the best long-term approach may be to pursue realistic, incremental policy change that delivers modest, but substantive, improvements over time.

Reform efforts should prioritize areas where Rhode Island is the worst of the worst. Some locals are pushing to eliminate or reduce the sales tax, but Rhode Island is in the middle of the pack on sales taxes, whereas it is the worst in the country in its unemployment-insurance system. Bringing some sanity to that system will take some doing. Benefits ought to be reduced to the national median, but this would prove exceedingly difficult politically in Rhode Island. Reform efforts should instead focus initially on eliminating market-distorting subsidies to the system’s most frequent users, such as the seasonal tourist businesses, and reforming the draconian successor-business rules.

The state could pursue a politically palatable “grand bargain” on revenue-neutral tax reform, in which income taxes are modestly raised on top earners in exchange for business-tax reform—such as an elimination of the 7 percent sales tax that businesses pay on their utility bills. This would particularly help small businesses.

Rhode Island must pare back its regulatory regime—and as a small, economically depressed state, where residents are never more than a short drive from the border, Rhode Island can’t afford to have its own regulatory regime, anyway. It should conform its regulations as close as possible with neighboring Massachusetts—not because Massachusetts represents an ideal but because Rhode Island cannot afford to lose businesses and residents to its neighbor. “If you’re licensed to do it in Massachusetts, you’re licensed to do it in Rhode Island” ought to be the basic principle.

The state must begin rebalancing spending away from consumption and toward investment. Given the dilapidated infrastructure, spending on roads and bridges is inevitable. Since interest rates won’t be this low again, the time to do it is now. Cuts need to be identified to finance payments on an infrastructure bond for repairing bridges, highways, and school buildings.

Ultimately, though, Rhode Island has to reduce the size of its government—paring back taxes, spending, and regulation, and doing so over the long haul until it has a fiscally sustainable system that doesn’t strangle its economy. And somehow, the state’s leaders and residents need to rethink their views on development and free enterprise.

The state’s best bet for future economic growth is not to bribe companies to relocate but to encourage new entrepreneurial ventures that grow locally. It should take steps to foster entrepreneurship: waiving permit fees for the first year of new businesses; eliminating the minimum corporation tax; and promoting shared infrastructure such as co-working facilities, shared kitchens, and TechShop-style workshops—anything that fosters market entry and reduces capital requirements. For all its drawbacks, Rhode Island could be a promising environment for incubating new business concepts. Providence is big enough to be a major market but small enough to keep cost of entry low—as the success of a local online-news organization, GoLocalProv, demonstrates. Founded in 2010 with a small full-time reporting and editing staff, GoLocalProv has already become a major competitor with the Providence Journal. Benefiting from weak competition and easy access to local media buyers, it penetrated the market quickly and developed a profitable business model that it is now taking to other markets such as Portland, Oregon. Its success probably wouldn’t have been possible in much bigger or much smaller markets.

Similarly, the success of Quonset Business Park, at a former naval base in North Kingstown, offers hope. Quonset has excellent infrastructure, pre-permitted sites for building, a single-zoning classification, and business-friendly, performance-based development standards. Because it smartly self-financed its port improvements, Quonset is exempt from the Corps of Engineers tax on imported cargo, giving the port portion of the park a tax advantage versus the competition. As a result, the park is home to 9,500 jobs—3,500 of them created since 2005. True, some of this growth is port-related and can’t be replicated elsewhere. But the state has clearly gotten a big lift from the park, and its strong performance offers hope for what Rhode Island could achieve if it changes the way it does things.

For anything serious to change, though, Rhode Islanders themselves must first understand the need for reform, and that will likely require something that’s been missing: political leadership. The November 2014 gubernatorial election may thus be a critical turning point in determining whether the state is willing to take a different path. In the meantime, Rhode Island should serve as a cautionary tale for any small or midsize state with delusions of grandeur.

Top Photo: kickstand/iStock