In 2013, a police lieutenant at the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey retired with an annual salary of $129,000; the next year, he began collecting a lifetime pension of $172,000, or one-third above his base pay. The officer had managed to juice up his annual pension through pay sweeteners provided by the Port Authority, including lots of overtime work. He was far from alone. An assistant operations manager at one of the Port Authority–controlled New York airports retired at a salary of $89,000, but soon began collecting a pension of $103,000, 16 percent above annual pay. An electrician quit working with a base salary of $76,000 and started collecting a pension of $79,000. These are extraordinary numbers, culled from a database of Port Authority pay practices provided by OpenTheBooks.com.

Formed nearly a century ago as a good-government unit to manage the bistate operations of the massive Port of New York, which spans both states, the Port Authority has evolved over the years into the worst kind of government operation: a vast but poorly run agency. Much of what’s wrong is reflected in its pay and retirement practices. In labor-friendly New York and New Jersey, unions have bullied the agency into giving away incredibly generous benefits to workers, and then the authority, through mismanagement, has proved unable to control key costs like overtime that drive pay even higher. The result: a workforce among the highest paid in government, even by the dizzying standards of public-employee compensation in the greater New York area. The Port Authority’s retirees regularly rank among the top pensioners in the lucrative New York state retirement system, to which most agency workers belong.

Meanwhile, the Port Authority is groaning under $20 billion in debt, struggling to make investments in local infrastructure, and levying steep fees on New York and New Jersey residents and businesses to keep itself afloat. (See “The Port Authority Leviathan,” Winter 2016.) For those stuck with paying for the authority’s plush benefits and mismanagement, one sign of hope is that New York governor Andrew Cuomo and New Jersey governor Chris Christie, who effectively control the Port Authority, have embarked on a search for a chief executive officer to fix the troubled agency—a task that would include grabbing control of soaring pension and persistently high overtime costs. Still, the Port Authority has struggled with these same issues for at least three decades, with little in the way of successful change to show for it. It may take something closer to a revolution to free area residents from the Port Authority’s grip.

The governments of New York and New Jersey were dragged reluctantly into forming the Port Authority in 1921. The two states often fought over operations at the Port of New York, until a federal judge admonished both to settle their differences with the mutual good in mind. The states set up a commission to explore how best jointly to run the port, and thus was born the Port Authority, modeled on the Progressive-era ideal of a government agency directed by enlightened bureaucrats, with input from an appointed board, independent of local politics.

Regional political leaders, initially opposed, soon discovered all sorts of uses for the Port Authority beyond its original mission. They folded the operations of a new Hudson River crossing, the Holland Tunnel, into the authority in 1930, for example, and handed it the mission to build additional ones. The agency assumed control of newly emerging air traffic by taking over the airports—even though the operation of the airports didn’t cross state lines. And political leaders began using the Port Authority as a dumping ground for their problems. The authority took over the bankrupt Hudson Tubes rail line in 1962 and assumed the task of trying to revive the West Side of lower Manhattan by constructing the massive World Trade Center complex.

As its role widened, the Port Authority swelled to gigantic proportions, with sprawling facilities and a huge payroll. Today, the Port Authority employs more than 7,800 workers, including nearly 1,700 police officers. Almost 70 percent of the agency’s workers are covered by collective bargaining, with more than 5,700 former employees currently collecting pensions. In 2014, the agency spent $1.19 billion on pay and benefits—an average of more than $150,000 per employee for an operation that largely hires blue-collar workers.

“Today, the Port Authority employs more than 7,800 workers, including nearly 1,700 police officers.”

In a region where public-employee unions wield enormous power, the Port Authority has proved an easy and lucrative mark for labor groups. The agency enjoys a monopoly over New York and New Jersey assets—like airports and tollways—that people need to use, and it has levied steep fees on residents and businesses in order to pay for generous worker contracts. When, for instance, the Port Authority assumed control of the Hudson Tubes in 1962, it acquired not only a bankrupt rail line but also militant unions that learned how to use the agency’s resources to burnish members’ pay and benefits. In 1973, the Brotherhood of Railway Carmen demanded a new contract with a 45 percent pay increase and enhanced pensions that would let members retire with full benefits after just 20 years on the job. When the Port Authority balked, the union struck for 63 days, creating chaos for the 40,000 riders using the daily service, dubbed PATH. As members of a rail union, the striking workers received strike benefits from a federal fund and eventually settled with the authority for a 19 percent pay increase over two years. Just five years later, the union demanded a three-year pay increase totaling 36 percent, and when the Port Authority again resisted, workers shut down the train line for another 81 days, ultimately securing a new deal that raised pay 35 percent over three and a half years and added pension sweeteners.

The combative rail unions also tangled with the Port Authority over work rules, especially reforms that might make the rail line more efficient at the expense of union jobs. In 1967, the PATH’s engineers’ union won an injunction to prevent the rail line from adopting walkie-talkies, which would enable workers to communicate with one another more easily and frequently, boosting efficiency. A judge eventually intervened, giving the PATH the go-ahead to deploy the technology. The engineers staged a sick-out in 1993 to protest management demands for work-rule changes, including an end to time off for blood donations. Only a compromise avoided another strike. In 1997, signalmen threatened to strike when the Port Authority initiated a policy that allowed supervisors to discipline workers taking too much time off for illness or injury. The union wanted members to be able to miss up to 40 days without ramifications; over time, the parties settled on ten days of sick time.

In the 1970s, frequent work stoppages and trains regularly getting stuck in tunnels prompted the New York Times to observe that the PATH was “no tunnel of love” for commuters. For rail workers, it was a different story. PATH employees, who not long before had worked for an insolvent private railroad, became among the highest-paid rail workers in the greater New York area. In 2014, according to OpenTheBooks.com data, the top-earning rail employee at the Port Authority was a unionized maintenance supervisor, who took home $216,378—more than half of it in overtime. Several union colleagues did nearly as well, frequently surpassing their white-collar, nonunion supervisors in pay. In fact, five of the top ten compensation leaders in Port Authority rail operations in 2014 were union members, including a track foreman who earned $208,994 and another who brought home $206,295. The base salary of an experienced conductor is $74,173, though the top-earning conductor in 2014 took home $156,343, thanks to overtime and other pay add-ons. On average, Port Authority rail workers earned $91,000 each in total pay in 2014, and that’s not counting the steep cost of benefits, which add about 55 percent beyond salary to the cost of employing a worker.

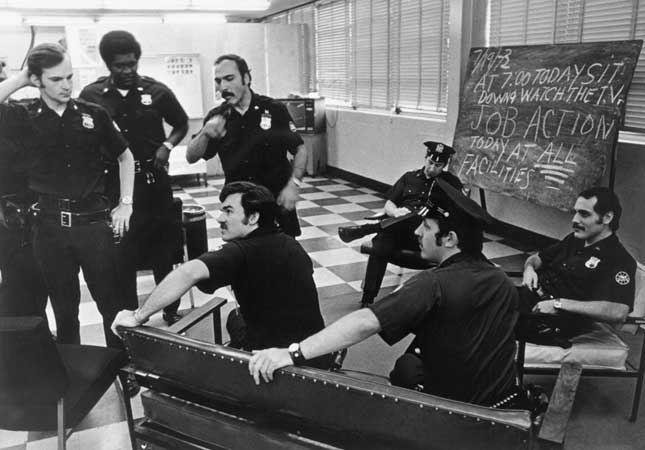

If work stoppages, slowdowns, and PATH strikes weren’t enough to test the patience of area residents, the Port Authority’s police union has also used its leverage to demand higher pay and steeper benefits for members, whom the union once claimed were underpaid. In March 1972, the cops disrupted vehicle traffic in a job action that snarled the approaches to the Hudson River crossings connecting New York and New Jersey. The action bolstered the union’s negotiating position, and it won a 25 percent pay increase over two years. Barely 15 months later, the union threatened another job action when the Port Authority, trying to cut costs, announced that it would start using civilians to perform some non-safety jobs that cops were then doing. Asked about what his members might do to tie up traffic, the head of the police union said, “Anything is conceivable.” The agency backed off, avoiding a showdown, but the issue arose again in 1979, with several hundred off-duty officers disrupting operations at the authority’s midtown Manhattan bus terminal in a dispute over pay and the hiring of more civilians.

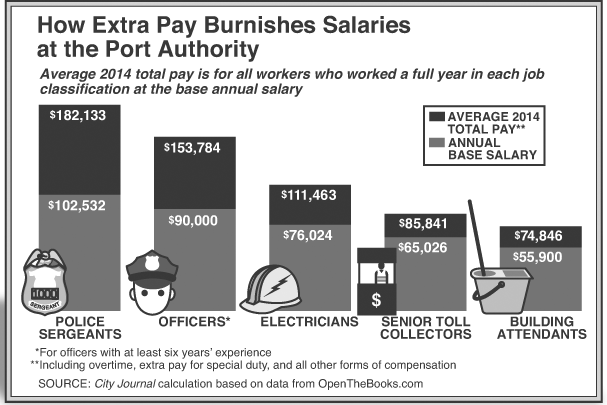

From Port Authority employees’ perspective, the confrontations have yielded impressive results. A 2012 study by the Citizens Budget Commission found that the agency’s public-safety force—one of the nation’s largest—is “paid more generously than those of most other local, state and federal law enforcement agencies,” with senior officers’ pay averaging between 25 percent and 48 percent higher than compensation of similar officers employed by New York–area local governments. Only cops working for Nassau and Suffolk Counties receive more generous compensation (and the jaw-dropping cost of Nassau’s police force is a major reason that the state has placed the county, one of the nation’s richest, under a financial control board). The average base pay of a Port Authority officer after six years is $90,000, but officers (like other authority workers) have many ways of increasing compensation, including longevity pay based on years of service, extra payments for work done under non-regular conditions (such as night or holiday shifts), uniform allowances, and the most lucrative category—overtime pay. In 2014, the 870 Port Authority officers earning the top-tier base pay of $90,000 annually enjoyed an average of $153,784 in total cash compensation, with $46,192 per officer in overtime pay, nearly $5,500 per worker in longevity compensation, and $7,511 per worker in extra pay for working under unusual circumstances.

The Port Authority has an even tougher time managing the overtime of its senior public-safety staff. The department’s 123 full-time sergeants earned a base-salary average of $102,532 in 2014, but total compensation for these workers was an astounding $182,133 per officer, thanks to $56,539 per worker in overtime and $9,492 per worker in pay differentials for unusual shifts. In its 2012 study of regional police departments, the Citizens Budget Commission noted that many police forces, including New York state troopers and New York City police officers, don’t receive pay differentials for duties such as holiday work, which are typically assigned in public safety on a rotating basis.

Other authority unions have secured similarly plush compensation for their workers. Toll collectors, represented by the Transport Workers Union, enjoy a base annual pay that tops out at $65,026 annually for the most senior members—for a job that requires no special skills. Total compensation for this senior group averaged more than $85,841 in 2014, thanks to some $7,600 in overtime and $4,030 per employee in extra pay for work performed under special circumstances. Buildings and grounds workers at the agency’s facilities earned a top average base pay of $55,900 in 2014, with total pay averaging $74,846 for those who worked full-time at that pay. That included an average $14,936 per worker in overtime. Electricians, represented by the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, top out at an annual base pay of $76,024; the 100 of these workers employed full-time in 2014, however, earned an average $111,463 in total compensation, with nearly $29,455 per worker in overtime.

Problems managing and restraining overtime pay have plagued the Port Authority for years—a testament to the agency’s inability to budget properly and supervise workers adequately. A 2011 audit by the New York state comptroller noted that “overtime flows like water” at the agency. Three years later, the New Jersey Courier News observed: “Among the sure things in this world besides the inevitability of death and taxes are stories . . . about how much over budget the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey went in paying overtime.” Published articles about the agency’s efforts to control overtime date back to the mid-1980s. A typical example: a November 1986 New York Times story reported that Port Authority overtime costs would grow by nearly 25 percent that year, despite an agency pledge to cut total compensation. Little has changed. In 2014, 5,360 Port Authority workers received overtime, with about 100 effectively doubling their base salary. Of the remaining workers employed by the agency, 2,200 worked in nonunion jobs that don’t qualify for overtime. Only 289 of the thousands of authority employees who qualified for overtime failed to get it in 2014. “Management has no clear strategy to achieve its own benchmarks and goals for curbing costs,” the New York state audit noted in 2011.

A big reason for the overtime cost explosion is that the Port Authority made the questionable decision in the past to try to save money on expensive benefits—which average about $55,000 per employee—by hiring fewer workers and instead paying overtime to current ones. The authority wound up cultivating not savings but an uninhibited culture of overtime, which it now seems incapable of changing, as evidenced by data that show workers piling on extra hours as they near retirement, to spike pensions. That and the fact that the retirement system bases lifetime benefits on total compensation have added more to the agency’s costs than pay data reflect.

Even by the standards of other public-sector retirement programs, the Port Authority’s pensions are incredibly generous. A 2011 study by the New York state comptroller found that 71 of the top 300 pensioners in the New York state retirement system were Port Authority retirees, though only about 5,750 members of the system’s 430,000 current beneficiaries worked for the agency. Like many public-sector workers, authority employees can qualify for full pensions with less time on the job than can private-sector workers. In 2013, for instance, a Port Authority police sergeant retired after 20 years on the job with a pension of $92,500, representing more than 85 percent of his annual base pay during his final working years. That same year, an officer with 25 years’ service began collecting a pension of $95,800—105 percent above his base pay during his final years on the job. Non-public-safety agency employees must work longer to collect a full pension but can still take home sizable retirement checks in a shorter time than is typical in the private sector. A unionized supervisor at one of the area’s airports retired after 30 years of work in 2013, with a final salary of $69,900, but began collecting an annual pension of $83,000.

One consequence of these earlier-than-usual retirement schedules is an unusually high ratio of pensioners to current workers, with approximately one Port Authority pensioner for every 1.2 active workers. (PATH employees at the Port Authority are part of another retirement system for rail workers.) The price for having so many retirees adds up. In 2014, authority pensioners collected $277 million in retirement pay from New York State. Annual payments by the Port Authority to the New York state retirement system are soaring, rising nearly 135 percent, to $143 million from 2009 to 2014. Annual pension contributions for public-safety workers are particularly high, relative to payroll, increasing from $32 million, or 16 percent of payroll, in 2009, to $71.4 million, or 28 percent of payroll, in 2014. Those costs are likely to keep rising fast, thanks to an ill-considered decision by the Port Authority years ago to place its employees, including those from New Jersey, in the New York retirement system, where they’re protected by an unusually strong state constitutional clause that makes it impossible to change current worker pensions—even for work they’ve yet to perform.

Over the years, Port Authority management has continued to make questionable decisions on pension policies that suggest that it couldn’t care less about rising costs. In 2002, for example, the agency began giving bonuses to top managers and letting them count that money as part of their pay, in order to boost their pensions. The practice stopped only when a New York state comptroller audit in 2011 discovered the bonuses and ruled that they couldn’t be counted toward pensions. Considering who was getting the benefits—the agency’s chief financial officer, general counsel, and chief administrative officer were among the recipients—the bonus plan clearly appeared as a perk that the managers had awarded themselves, after years of watching unionized staff spike their own pensions.

“One consequence of early retirement schedules is an unusually high ratio of pensioners to current workers.”

All this irresponsibility would add up to a damning indictment of the Port Authority under any circumstances. But the agency’s missteps are even more worrisome in light of the doubling of its debt in recent years to help pay for redeveloping the World Trade Center site after September 11 (another project that it has bungled). The agency also needs to begin financing investments that it desperately needs to make in infrastructure around the region, including a projected $10 billion for a new bus terminal in Manhattan. To keep its finances from sinking completely, the agency has already sharply boosted fees on bridges and tunnels, up for cars from $8 in 2008 to $15. The result has been a half-billion dollars in additional tolls and fares paid by users of these important facilities. The authority has also kept raising the fees that it charges airlines at its airports. In 2014, it collected $242 million more in aviation fees than it did five years ago. United Airlines, the major tenant at the Port Authority’s Newark Airport, says that its gate fees there are the highest in the nation, 59 percent higher than it pays at Chicago’s O’Hare. Among the reasons United cites for the inflated charges: the high costs that the Port Authority pays for its airport police force.

The Port Authority’s continued effort to subsidize its high labor costs and money-losing operations with spiraling fees is generating growing controversy. In a 2013 report to Congress, the Government Accountability Office questioned the authority’s recent toll hikes in light of a federal statute that holds that interstate-agency crossing rates must be “just and reasonable.” The GAO criticized the Port Authority for a lack of transparency in setting the fee increases. The Port Authority refused to provide the GAO with copies of its own audits of its operations, the report noted. The Automobile Club of America, meantime, has sued the authority over the toll hikes, charging that they’re illegal because they’re being used to fund other, money-losing agency operations. The lawsuit is still in court. United Airlines has similarly sued the Port Authority over its stratospheric airport fees, contending that the agency is milking airlines to fund other operations. The controversies illustrate a major flaw in the governance of an independent agency with significant taxing power but that stands outside the jurisdiction of any elected official. Taxpayers don’t seem to know whom to hold accountable for the fiscal consequences of authority mismanagement.

Gaining control of the Port Authority’s workforce will be a major task of the agency’s new chief executive, but he’ll need the support of the governors of New York and New Jersey. As an independent body, the Port Authority can make changes in its workforce policies and practices without passing legislation. One already-proposed reform would end unions’ right to bargain over changes in health benefits, which would enable the agency to impose money-saving changes. Most private employers can make such alterations to their health plans without bargaining with workers (and if they don’t like the changes, employees have the right to seek employment elsewhere). The Port Authority should have the same prerogative. In fact, in 2012, the agency announced just such a change to its policies, but Governor Cuomo nixed it after unions pressured him. The agency needs to revisit that policy.

The Port Authority should also stop placing workers in the New York state retirement system. That way, it could escape New York’s constitutional provision that blocks any reform for current employees. Instead, the agency should explore other options, including creating an independent pension plan outside New York State for new workers.

The Port Authority is custodian of some of the most vital public assets of the greater New York area. One look at its compensation practices makes it clear that the agency has often operated those resources more for the benefit of its workforce than for the people of the region. That needs to change—and soon.

This is the second in a series of articles on the Port Authority.

Top Photo: The Port Authority imposes exorbitant tolls at Hudson River crossings to feed its porcine budget. (JOHN MUNSON/STAR LEDGER/CORBIS)