For decades, the United States has recognized the problem of behemoth school districts: too often, they are unwieldy, opaque, and low-performing. In 1970, New York City (with the nation’s largest district) delegated some authority to 32 subdistricts, each with its own board. For years, leaders in Los Angeles (the second-largest district) have discussed breaking up the district; similar conversations are taking place in Clark County, Nevada (the fifth-largest). In various cities, more affluent neighborhoods have sought to secede from large districts. Since the 1990s, chartering has been used to create more manageable small-school networks, and the “portfolio district” model aimed to allow semiautonomous schools inside giant districts. More recently, policy writers, including Walt Gardner and City Journal contributing editor Howard Husock, advocated breaking up large urban districts, with Husock arguing that this would reduce teachers’ union power. In 2018, North Carolina’s legislature studied breaking up the state’s massive districts, and in 2022, Wisconsin leaders introduced legislation to break up the long-struggling Milwaukee district.

For all this activity, however, too many too-big districts remain. In the past, reform efforts didn’t go far enough or couldn’t secure sufficient political support. Today, when frustration with one of these large districts becomes acute, it seems easier to address the particular symptom than the underlying problem. But Covid-19, fierce battles over curricula, and mounting public distrust of enormous systems and out-of-touch “experts” may make it possible to end the era of behemoth districts.

Instead of focusing on the distressing academic performance of these systems—to which the public and policymakers seem inured—reformers should make their case in terms of parental and community control, democracy, and pluralism. Public leaders would be more amenable to change if they appreciated how historically unusual massive districts are as well as the antidemocratic ideas that enabled their development and how they thwart local governance.

American K–12 public schooling was largely decentralized just a century ago. In 1920, fewer than 22 million public school students attended 270,000 public schools. The average school had only 80 students. In 1940, the first year for which data are available, America had 117,000 school districts. The average district had just 217 students and two schools.

The decisions of such small, geographically based governing units often reflected community consensus. A hundred or so families, who mostly knew one another, could more readily develop a sense of solidarity. When disagreements arose, a parent had direct access not just to a teacher or principal but also the school board and superintendent. This model of governance is not beyond criticism: absent overarching state or federal rules, some districts could (and did) provide inadequate schooling and could (and did) unjustly discriminate. But individuals in these hyper-local, democratically controlled school systems belonged to vibrant communities; their public schools were genuine community institutions.

Leaders concluded in the first half of the twentieth century, however, that American K–12 schooling was too decentralized. A movement to standardize and professionalize K–12 education across the United States began in the Progressive Era. It was largely an elite effort to overcome the putatively unsophisticated ways of families and neighborhoods. Maintaining so many small schools and one-school districts was expensive and required too many boards, administrators, facilities, and educators, the thinking went. Larger schools and districts would enable economies of scale. Hiring, human resources, and purchasing could be centralized; more courses and programs could be offered; resources could be spread more fairly. Further, if a state government oversaw only 100 districts instead of 1,000, state rules related to teacher certification, graduation requirements, district finances, and much else could be administered more easily.

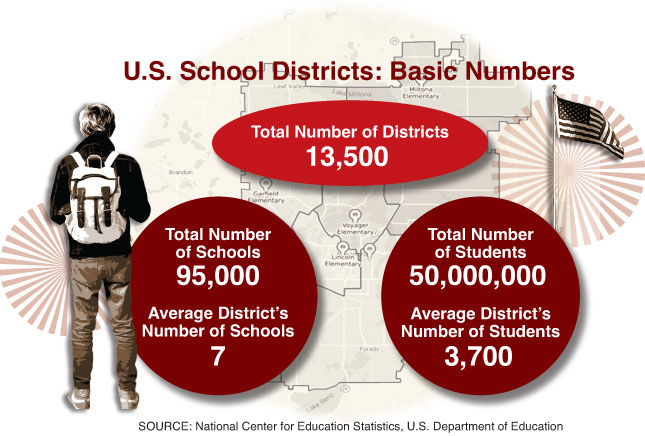

As the century proceeded, states amassed authority that had long been delegated to local boards. Federal courts and Congress forced the hands of state and local officials on segregation, special education, and more. (More recently, such battles have concerned issues like Race to the Top, Common Core, teacher evaluations, and standardized tests.) As a result of such efforts, about 100,000 school districts vanished between 1940 and 1970. Today, fewer than 13,500 exist, about 11 percent of the 1940 figure.

Consolidation may have accomplished some of its goals. In a paper for The Journal of Law, Economics, & Organization, economists Christopher Berry and Martin West found that the twentieth-century reduction in districts produced modest improvements in efficiency and student educational attainment (though any such gains were outweighed by the negative effects of larger schools). Some research suggests greater efficiency in moving from very small to small or average-size districts. In a report for the left-leaning Center for American Progress think tank, Ulrich Boser argued that the United States could save $1 billion by consolidating very small non-remote districts—that is, districts not in sparsely populated rural areas and with fewer than 1,000 students. One study found that consolidating very small districts also lifted local home values and rents.

But research findings are not uniformly positive. A 2021 study of recent consolidation efforts in Arkansas found little to no benefit in student achievement and no evidence of improved economies of scale in consolidating very small districts. A Texas study found negative cost and achievement effects from consolidation. Research is mixed on the general question of whether larger districts produce better results than smaller ones. And questions persist about the role of competition in areas with more districts (and therefore more choice). In a study for the American Economic Review, economist Caroline Hoxby found that more districts in a given area can lead to lower spending and higher achievement (though Jesse Rothstein contested those findings in a paper for the National Bureau of Economic Research). One study found that breaking up a huge district could increase home values.

Even allowing that consolidating the smallest districts into average-size districts might yield some financial or academic benefit, it’s far from clear that similar benefits will accrue when growing districts from 1,000 to 50,000, 100,000, or 500,000 students. Some of America’s largest districts are terribly low-performing: according to the Trial Urban District Assessment of the National Assessment of Educational Progress, a respected test that measures the performance of many of the nation’s big-city districts, one in four of these districts’ eighth-graders was reading proficiently; the proportion falls to one in five in Baltimore, Cleveland, Dallas, Detroit, Milwaukee, Philadelphia, Los Angeles, and Houston. Many of these districts also spend vast sums: according to 2019 figures from the census, San Francisco and Atlanta spend more than $17,000 per student; Washington, D.C., more than $22,000; Boston more than $25,000; and New York City more than $28,000.

True, large urban districts typically have substantial concentrations of poverty and high costs of living. Nevertheless, arranging city schools into massive districts didn’t produce extraordinary efficiency—much less, consistently outstanding achievement. Indeed, a recent study by the Thomas B. Fordham Institute compared school performance in the nation’s 50 largest metro areas and found that Miami, anchored by the nation’s fourth-largest district, topped the list, but Las Vegas, anchored by the nation’s fifth-largest district, came in next to last.

Despite substantial consolidation over the last century, most districts today are still a manageable size. The average district has only about seven schools and about 3,700 students, and many districts remain quite small. In 2002 (when the U.S. had about 1,000 more districts than today), 72 percent of districts had fewer than 2,500 students, and almost half of districts had fewer than 1,000 students. Most families with children in traditional public schools enroll them in districts of about a half-dozen schools and a few thousand students. That is certainly small enough for a parent to have access to key decision-makers.

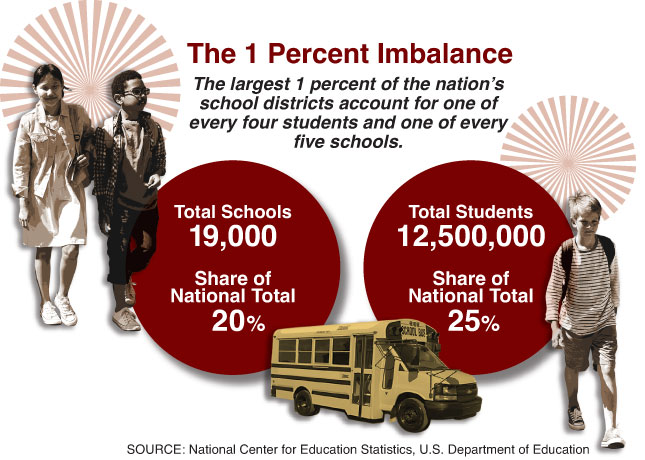

But some American school districts have gotten so large that parental agency inside those systems has become negligible. In such gargantuan districts, one parent’s voice—even the collective voice of ten or 100 families—is a drop in the ocean. My analysis of the most recent federal data available finds that the largest 1 percent of districts have about 12.5 million students and about 19,000 schools—representing 25 percent of the nation’s public school students and 20 percent of its public schools. Put another way, these giants make up just one of every 100 districts, but they account for one of every four students and one of every five schools. Today, 30 districts have more than 100,000 students, and ten have more than 200,000 students.

For the most part, these enormous districts are located in big cities and their ring suburbs. The nation’s three largest districts serve the nation’s three largest cities: New York City, Los Angeles, and Chicago. But the top 1 percent also includes Dallas, Philadelphia, San Diego, Milwaukee, Detroit, Seattle, Atlanta, and Boston. In a few states, school-district lines are the same as county lines, so a huge district sometimes serves a populous county that includes a major city (such as Florida’s Miami-Dade County district or Nevada’s Clark County, which includes Las Vegas) or lies just outside a major city (Maryland’s Montgomery County district and Virginia’s Fairfax County, both just outside Washington, D.C.).

The location of these districts is relevant for two reasons. First, this is where America’s political, cultural, and media elites live—so these districts get a disproportionate amount of national attention. A consumer of news would think that these outlier districts represent the state of American K–12 education. They don’t.

Second, these areas are among the nation’s most diverse. Differences are found across many dimensions: wealth, education attainment, race, ethnicity, culture, religion, and more. Though these places are often solidly blue politically—meaning that they typically vote for Democratic candidates—that broad allegiance can mask significant differences in ideology and priorities.

It’s not hard to see why these areas have been roiled by high-profile political battles and why many Americans believe that the nation’s public schools are so troubled. People care deeply about their local schools, especially if they have kids attending them. As districts grow in size, each citizen or each parent has less of a voice, and interpersonal bonds are weakened. They don’t see the superintendent and board members at the grocery store; they read about them in the news. Reaching consensus becomes harder. Feeling that their views on the most important matters aren’t being heard and that there is nothing that they can do about it, frustrated parents confront officials in board meetings and online. These fights get broadcast far and wide. (See “The Parents’ Revolt.”)

“Deconsolidation wouldn’t touch the vast majority of districts, and it wouldn’t be a federal initiative.”

Over the last two years, battles have raged about Covid-related issues and cultural matters: school-naming policies and closures in San Francisco; curricular decisions in Loudoun County, Virginia; and mask mandates in Chicago (all top 1 percent districts). But major education battles predate the pandemic. Recent years have seen arguments over school discipline in Broward County, Florida; magnet schools in Fairfax County, Virginia; and gifted education in New York City (all top 1 percent districts). Such fights are an evergreen phenomenon: a law-review article written about New York’s 1970 decentralization effort noted that advocates of decentralization “maintained that the centralized school system could never be responsive to the individual needs of all the socio-economic groups in the City” and that the centralized city “acts on a city-wide basis and is therefore not sensitive to particular community problems, nor capable of solving them.”

It’s impossible to keep America’s philosophical and political differences out of education policy. The question isn’t how to avoid or suppress such battles but how to arrange our institutions so that these fights don’t metastasize into perpetual wars. A big part of the answer is relying on small communities, where people know one another, voices can be heard, and consensus can be formed and compromises struck. Enormous districts might promise efficiency and fairness, but they cannot manage our inevitable disagreements. Forcing from a central office a single answer on contentious issues doesn’t lead to agreement but to frustration, resentment, and sometimes impassioned public opposition.

Restoring small districts won’t resolve any particular policy argument by itself. Over the last several years, smaller districts have debated the same issues as larger districts. Board meetings have run hot, voter turnout has been high, school board seats have been contested, retirements have increased, and recall efforts have been mounted. But while threats against public officials are intolerable, vigorous public debate among parents and community members over the future of their local public institutions defines civic engagement—and democracy. Civic virtue in a pluralist, democratic republic doesn’t just require our participation; it also requires our acceptance of the lawful democratic decisions of citizens elsewhere.

A district-deconsolidation movement wouldn’t touch the vast majority of districts, and it wouldn’t be a federal initiative. It wouldn’t even be a uniform statewide reform that similarly affects all districts and schools. Instead, it would be a targeted policy proposal, narrowly tailored to a specific problem. But in the affected locations, it would represent a serious departure from the half-measures of the past.

Previous efforts have sought to distribute some of a district’s powers to subunits or schools, while maintaining the integrity of the district itself. For example, in many huge districts, regional superintendents oversee sets of schools. Site-based management reforms gave principals a degree of freedom from the central office. New York’s 1970 restructuring plan gave 32 zones control over local elementary and middle schools. The “portfolio district” model of more recent vintage allows multiple entities to run semiautonomous schools inside the district. But in all such cases, the district’s central school board and superintendent retain most power. In the New York City example, the central office maintained the authority to tax and distribute funds to its 32 local boards, the powers of the community boards were subject to the policies of the citywide board, and the central office controlled all matters with citywide impact. So, absent a true deconsolidation of a massive district, the fundamental problem would remain: the limited power of parents and citizens inside a distant, hulking administrative body.

Deconsolidation would take a different approach. State governments would concentrate on the nation’s largest 1 percent of districts, roughly those with more than 40,000 students. A state could begin by passing a law requiring those districts to be deconsolidated by a future date—say, within five years. The resulting districts would be capped at an enrollment of 10,000 students. (The current Milwaukee proposal would break the 75,000-student district into four to eight districts.)

A state government would have several options for executing the plan. It could task the district itself with developing a deconsolidation proposal. Since the district’s board (and staff) would have the most knowledge about the system’s history, demographics, and operations, it might be best positioned to develop the most prudent proposal. If the state decided that the district could not objectively deconsolidate itself, the new law could create a temporary commission to do the work or have the state board of education or state department of education take charge. Since the breakup would raise legal issues (e.g., related to contracts, ownership of facilities, debt obligations, and consent agreements) and implicate sensitive historical and social matters (e.g., related to immigration, redlining, desegregation, and employment), any entity tasked with the deconsolidation plan would need to possess deep policy, legal, and historical knowledge.

As Howard Husock notes in a recent paper for the American Enterprise Institute, any effort along these lines will come with serious complications, including what to do with citywide specialty schools and how to ensure that the reforms don’t lead to new districts with “clusters of especially disadvantaged students.” One essential component of a successful plan would be a state-led, weighted, student-based funding formula, under which funding is based not on existing teacher salaries or current school budgets but on each new district’s enrollment and its students’ characteristics. This would ensure that each new district has the resources needed to serve its students—and that districts with significant numbers of low-income and special-needs students are adequately funded. Each new district would possess the same taxing and borrowing authority as existing districts; state dollars would fill the gap when a district is incapable of raising sufficient local funds.

Since the ultimate goal of this reform is to create small, democratic, self-governing education bodies, each new district will need to have its own board and administration. Beyond that, though, different states—even different regions within a state—could approach deconsolidation differently. For example, one state could go about this process gradually, breaking off one new district annually. This would be less of a shock to the system, and state and local leaders could learn and make adjustments along the way. Another state could take several years to plan but then relaunch the new arrangements in one stroke. One state could choose to create geographically compact districts, each with the same number of students and primary and secondary schools. Another could deconsolidate based on school type, with each new district having only elementary, middle, or high schools or specialty schools. One state could allow the new districts to assign students to schools; another could require that each new district allow students to choose from among the district’s schools.

Whatever a state decides, it should avoid setting arrangements in stone. Flexibility is important. Regardless of its flaws, a large, long-standing district will have valuable programs and customs suited to its community. No matter how well planned, bold reforms will unsettle a great deal, unwinding some successful practices and causing new problems. In the first few years, the state and its new districts may discover more sensible arrangements related to district composition, shared services, enrollment systems, facilities management, transportation, choice, and more.

Large districts and those that benefit from them will certainly object to deconsolidation. Running a system with a billion-dollar budget confers prestige. Those in charge of such districts wield political power that will be hard to give up. Private providers of goods and services (such as books, professional development, and school meals) prize the big contracts that they score with massive districts. Unions and other professional associations have more power when they can organize on the scale of a huge district. They will argue that breaking up districts will lead to inefficiencies and duplication of services. Why, they will ask, should we have five school boards, five central offices, and five superintendents, when we can have just one of each?

Whether such large districts are actually more efficient remains debatable. But advocates of deconsolidation should be clear that there is more to public school governance than efficiency. After all, separation of powers, bicameralism, federalism, democracy, and individual rights can be considered inefficient.

In most schools and in most places, families have a good bit of influence. Because so many education decisions are made at the school or classroom level, parents typically work quietly with educators to solve problems. Surveys show that most teachers strongly support parental engagement, that most parents of public school students are satisfied with their child’s education, and that the public is generally satisfied with local public schools.

But parents and community members sometimes find themselves shut out of district governance. When that happens, school choice has often been put forward as an answer. Small districts are another answer. These districts’ enduring nature speaks both to their capacity to meet a wide array of needs and to their integration into individuals’ and families’ lives. They reflect the customs and preferences of the geographies they serve and help build solidarity at the community level. They offer citizens the opportunity to participate in local political life by shaping an institution designed to form future citizens. For those who believe in localism, community, and democracy as well as parental power, breaking up enormous school districts should be a new priority.

Public schools are valuable not just because they teach young people reading or job skills but because they enable a community to pass its values on to the next generation. We shouldn’t assess a school system based solely on math scores or graduation rates per dollar spent. We should also ask whether local citizens and parents feel as though the schools are theirs: Do the schools reflect their priorities and give them a way to engage in key decisions? Parental and community control of public schools makes sense to most Americans—but for decades, K–12 policy has been far more interested in goals other than local control.

The reform of America’s K–12 schools has long been guided by principles like efficiency, accountability, college-readiness, fairness, and transparency. All these are important. But we seem to have lost our commitment to schools as community-led institutions. Seldom does one hear that public school reform should prioritize the will and engagement of local citizens, even though, in many places, that principle is alive and well in practice. In big cities and the areas surrounding them—places where the need for strong, responsive, community-oriented schools is often most acute—it’s time to reestablish the principle of local, democratic control.

Top Photo: Some American school districts have gotten so large that parental influence becomes almost impossible. (OCTAVIO JONES/REUTERS/ALAMY STOCK PHOTO)