Last fall, a week after the worst massacre of Jews since the Holocaust, the New York Review of Books ran a short open letter from “writers and artists who have been to Palestine to participate in the Palestine Festival of Literature.” The authors described their “fear” that they were “watching an ethnic cleansing on a scale unseen in decades.” Not in Israel—where a Hamas-led horde had just massacred everyone it could find—but in Gaza, where “Israel is executing the largest expulsion of Palestinians since 1948 as it bombs Gazans without discrimination.”

What precipitated this “terrifying escalation”? The professional writers employ a passive construction so shameless it would give my seventh-grade English teacher an aneurysm: “On Saturday, after sixteen years of siege, Hamas militants broke out of Gaza. More than 1,300 Israelis were subsequently killed with over one hundred more taken hostage.” The authors’ styling leaves the critical question—by whom?—to our imagination. Moreover, it fails to acknowledge that Israel is even fighting an enemy—much less one that expresses its grievances, legitimate or not, by burning families alive. Bad things can happen, by chance or comeuppance, to Israel, but only Israel does bad things—in fact, the worst things possible. Its enemies, by contrast, are not just victims but blameless.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

This is no mere moral inversion. It is childish. And it should come as no surprise that the letter’s first named author is Ta-Nehisi Coates.

A glowing New York cover story on Coates and his forthcoming book has put the award-winning author of Between the World and Me and “The Case for Reparations” back in the spotlight. Though his new book is broadly about oppression, “Palestine,” the de-Judaized name for the territory on which Israel sits, is “his obsession.” So it is for many conspiracy theorists.

Israel is the natural endpoint for today’s most popular conspiracy theory, a vulgar form of intersectionality that considers all conflict the product of overlapping forms of oppression. College students call for smashing capitalism by supporting Iranian-sponsored terrorists. Climate activist Greta Thunberg has reinvented herself as a keffiyeh-clad banshee. Coates, who speaks neither Hebrew nor Arabic and took one trip to Palestinian areas, casts his lot with them. “That kid up at Columbia, whatever dumb sh[**] they’re saying,” he says, “they are more morally correct than some motherf[***]ers that have won Pulitzer Prizes and National Magazine Awards.”

Apparently, maximalist anti-Israel demonstrators are “morally correct” for demanding Israel’s elimination, and, as Columbia students like to tell their Jewish classmates, insisting that Jews “go back to Poland.” Yet Coates’s musings seem stuck in the pre-October 7 era, a quaint time in which many pretended that the “occupation” referred to Israeli control of particular disputed areas, not to Jewish sovereignty over any part of Israel. “What is the experience that justifies total rule over a group of people since 1967?” Coates asks, rhetorically, referencing not Israel’s 1948 founding but the year when it conquered the West Bank, Gaza, East Jerusalem, and other territories. But the discourse has raced past him, pivoting from a focus on what Israel does to what Israel is. The question now, for the “morally correct” brigade, is how to justify expelling Jews from their ancestral homeland.

There is no answer, of course, least of all from Coates. New York nevertheless insists, in one of its many dubious claims, that “many are now eager for Coates to lend his considerable influence to the deadlocked public conversation on Israel and Palestine.” “Influence” is the right word here, as opposed to, say, insight—there is nothing of that in Coates’s overwrought entry into the discourse.

His contribution consists, apparently, of making boilerplate claims about Israel’s depredations. “[A]s sure as my ancestors were born into a country where none of them was the equal of any white man,” he writes, “Israel was revealing itself to be a country where no Palestinian is ever the equal of any Jewish person anywhere.” Here he flattens two wildly different situations into one simple tale about “equality.”

Coates derides “the elevation of factual complexity over self-evident morality” and directs readers to, in his New York profiler’s words, the “plain truth of what he saw: the walls, checkpoints, and guns that everywhere hemmed in the lives of Palestinians” and other marks of division between Jew and Arab. Coates divines a deeper truth about the situation through abstract resonances between Palestinian life and the subjugation of black Americans. “In Coates’s eyes, the ghost of Jim Crow is everywhere in the territories,” New York summarizes. He knows because he feels it; his emotions are his insights. Israeli soldiers “stand there and steal our time,” Coates recalls, “the sun glinting off their shades like Georgia sheriffs.”

Perhaps, however, Coates’s faux-profundities fail to capture some tenable distinctions between the Jim Crow South and Israel. Among them: black Americans under Jim Crow did not reject a partition plan between two groups with competing claims to a piece of land; they did not launch a war of annihilation against a nascent country with the help of several national armies; they did not lose that war, then launch more wars, losing those, too; they did not reject multiple deals that would have given them what they claimed to want; they did not initiate terror campaigns against that country’s civilians; they did not use territory and funding given in hopes of achieving peace to launch missiles at cities.

But nowhere does Coates betray a greater misunderstanding of his subject than in his shallow analysis of the role the Holocaust plays in the contemporary Israeli imagination. As New York explains:

[Coates’s] affinity for conquered peoples very much extends to the Jews, and he begins the book’s essay on Palestine at Yad Vashem, Israel’s memorial to the victims of the Holocaust. “In a place like this,” he writes, “your mind expands as the dark end of your imagination blooms, and you wonder if human depravity has any bottom at all, and if it does not, what hope is there for any of us?” But what Coates is concerned with foremost is what happened when Jewish people went from being the conquered to the conquerors, when “the Jewish people had taken its place among The Strong,” and he believes Yad Vashem itself has been used as a tool for justifying the occupation. “We have a hard time wrapping our heads around people who are obvious historical victims being part and parcel of another crime,” he told me. In the book, he writes of the pain he observed in two of his Israeli companions: “They were raised under the story that the Jewish people were the ultimate victims of history. But they had been confronted with an incredible truth — that there was no ultimate victim, that victims and victimizers were ever flowing.”

Coates seems to believe that Israeli Jews feel licensed to do wrong because they consider themselves “the ultimate victims of history.” He believes, with many others, that a sense of victimhood entitles a people to revenge. It is understandable to project that view on Israel, which rose in the aftermath of millennia of Jewish suffering. But it is false. The lesson that Israelis have drawn from the Jews’ history of suffering is not that they are entitled to do evil to others. It is that the cost of power pales in comparison with that of powerlessness. What Coates misses, as he elides all context to denounce walls and guns, is the real lesson: no one else will protect the Jews, so the Jews will take great pains to protect themselves. While in the U.S., Holocaust education has been universalized into a tale about preventing “hate,” in Israel, its lesson is more particular and more powerful: Jewish blood is no longer cheap. If Coates cannot internalize that lesson and adjust his observations about Israel’s behavior accordingly, that only demonstrates the limitations of his moral imagination.

This confluence of intersectional nonsense and anti-Israel bile is hardly surprising. Coates’s works, especially Between the World and Me, rely on just-so histories and simplistic victimology analyses. They thus prefigure the anti-Israel narrative as told by Coates, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing. Moreover, the anti-Israel cause itself has become increasingly Coatseian—that is, emotive and irrational—as it cites “indigeneity” to explain why Jews don’t belong in their ancient homeland.

That this drivel has revived Coates’s standing as a public intellectual says nothing about Israel and little about the author himself, beyond reminding us of how glib sermonizing has come to define so much of our public debates and our politics. It does say something about those who have long treated Coates as a prophet to whom they can outsource their analysis of the world. No one is up to that job—certainly not someone whose critical-thinking skills are so adolescent, to put it charitably.

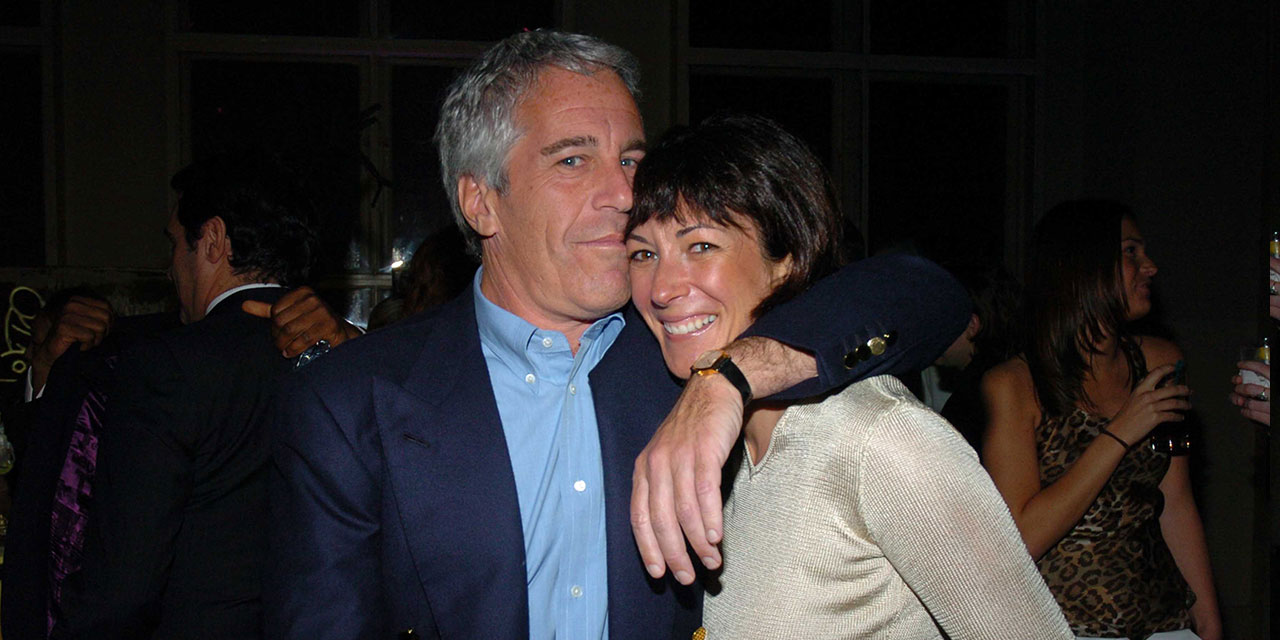

Photo by Carol Lee Rose/Getty Images